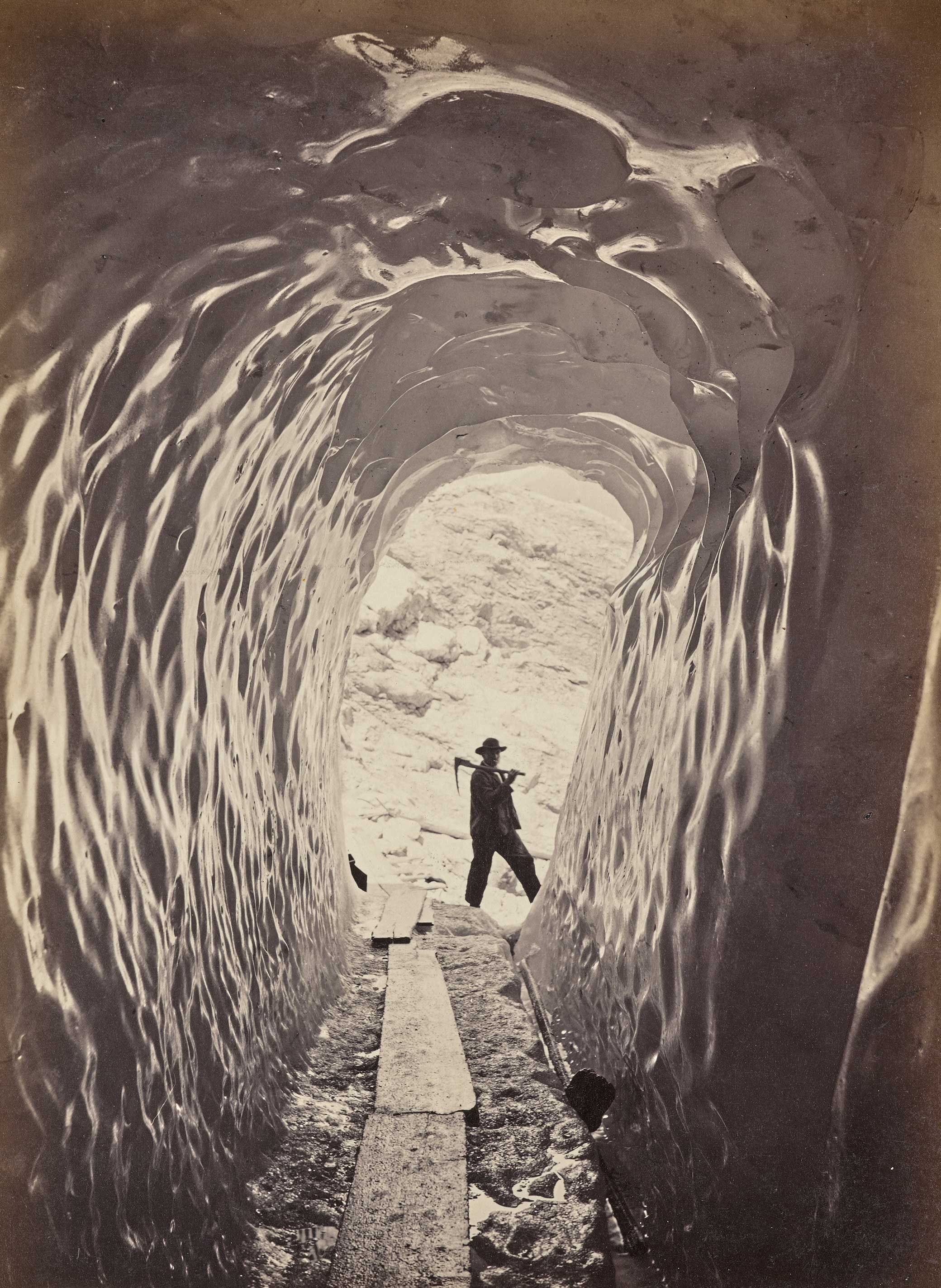

Grotte de Glace, Grindelwald, by Charnaux Frères, & Cie, c. 1880. The J. Paul Getty Museum. Digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program.

This summer, Lapham’s Quarterly is marking the season with readings on the subject or set during its reign. Check in every Friday until Labor Day to read the latest.

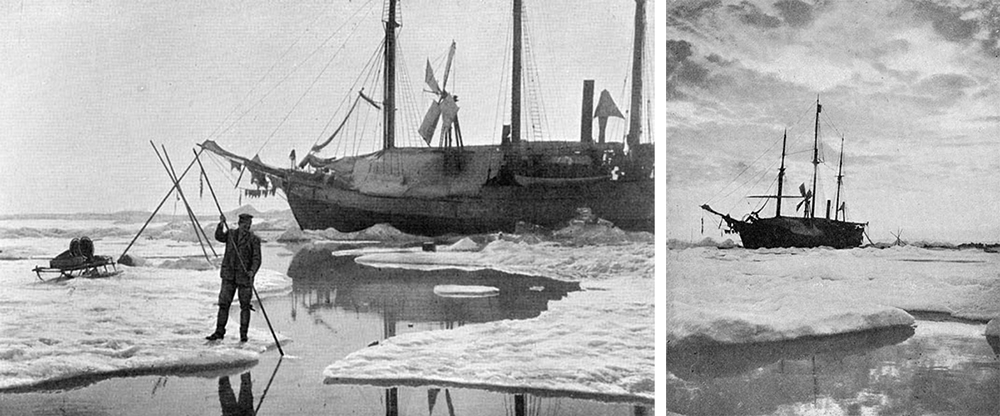

In the summer of 1894, Norwegian explorer Fridtjof Nansen had not yet left his ship, the Fram, to continue his journey to the North Pole on foot. (He never made it, but he did reach a latitude of 86°13.6′N in 1895—a northerly point record that would last for five years.) The longer Nansen remained on the Fram—the Norwegian word for “forward”—the more frustrated he became with the unhurried pace of his expedition. His innovation in the increasingly crowded field of arctic exploration was designing a ship that could withstand the pressure of moving ice and ride the ice pack as it drifted, pushed by the Arctic Ocean’s currents. But it turned out that following the whims of the ice and wind would not escort him directly to the North Pole; instead the ship charted a far more unpredictable path—sometimes heading north, sometimes not—one that meant he and his crew were often moving less than a mile a day: slow enough for him to disembark and do some cross-training in preparation for heading north on skis. There were still months to go until March 1895, when Nansen and dog-sled expert Hjalmar Johansen set off for a lonely year of eating walrus meat and being presumed dead—they wouldn’t meet another person until June 1896, when they crossed paths with another polar explorer, Frederick Jackson—but at least the days were getting longer as the summer solstice neared. Or maybe the never-ending sunlight just gave Nansen and his crew more time to be bored, as the book Nansen published after returning to Norway in 1896, Farthest North, suggests.

May 28, 1894

Ugh! I am tired of these endless white plains—cannot even be bothered snowshoeing over them, not to mention that the lanes stop one on every hand. Day and night I pace up and down the deck, along the ice by the ship’s sides, revolving the most elaborate scientific problems. For the past few days it is especially the shifting of the Pole that has fascinated me. I am beset by the idea that the tidal wave, along with the unequal distribution of land and sea, must have a disturbing effect on the situation of the earth’s axis. When such an idea gets into one’s head, it is no easy matter to get it out again. After pondering over it for several days, I have finally discovered that the influence of the moon on the sea must be sufficient to cause a shifting of the Pole to the extent of one minute in 800,000 years. In order to account for the European Glacial Age, which was my main object, I must shift the Pole at least ten or twenty degrees. This leaves an uncomfortably wide interval of time since that period, and shows that the human race must have attained a respectable age. Of course, it is all nonsense. But while I am indefatigably tramping the deck in a brown study, imagining myself no end of a great thinker, I suddenly discover that my thoughts are at home, where all is summer and loveliness, and those I have left are busy building castles in the air for the day when I shall return. Yes, yes. I spend rather too much time on this sort of thing; but the drift goes as slowly as ever, and the wind, the all-powerful wind, is still the same.

June 11

Today I made a joyful discovery. I thought I had begun my last bundle of cigars, and calculated that by smoking one a day they would last a month, but found quite unexpectedly a whole box in my locker. Great rejoicing! It will help to while away a few more months, and where shall we be then? Poor fellow, you are really at a low ebb! “To while away time”—that is an idea that has scarcely ever entered your head before. It has always been your great trouble that time flew away so fast, and now it cannot go fast enough to please you. And then so addicted to tobacco—you wrap yourself in clouds of smoke to indulge in your everlasting daydreams. Hark to the south wind, how it whistles in the rigging; it is quite inspiriting to listen to it. On Midsummer Eve we ought, of course, to have had a bonfire as usual, but from my diary it does not seem to have been the sort of weather for it.

June 23

I have seen many Midsummer Eves under different skies, but never such a one as this. So far, far from all that one associates with this evening. I think of the merriment around the bonfires at home, hear the scraping of the fiddle, the peals of laughter, and the salvos of the guns, with the echoes answering from the purple-tinted heights. And then I look out over this boundless white expanse into the fog and sleet and the driving wind. Here is truly no trace of midsummer merriment. It is a gloomy lookout altogether! Midsummer is past—and now the days are shortening again, and the long night of winter approaching, which, maybe, will find us as far advanced as it left us.

A dismal, dispiriting landscape—nothing but white and gray. No shadows—merely half-obliterated forms melting into the fog and slush. Everything is in a state of disintegration, and one’s foothold gives way at every step. It is hard work for the poor snowshoer who stamps along through the slush and fog after bear tracks that wind in and out among the hummocks, or over them. The snowshoes sink deep in, and the water often reaches up to the ankles, so that it is hard work to get them up or to force them forward; but without them one would be still worse off.

Every here and there this monotonous grayish whiteness is broken by the coal-black water, which winds, in narrower or broader lanes, in between the high hummocks. White, snow-laden floes and lumps of ice float on the dark surface, looking like white marble on a black ground. Occasionally there is a larger dark-colored pool, where the wind gets a hold of the water and forms small waves that ripple and plash against the edge of the ice, the only signs of life in this desert tract. It is like an old friend, the sound of these playful wavelets. And here, too, they eat away the floes and hollow out their edges. One could almost imagine one’s self in more southern latitudes. But all around is wreathed with ice, towering aloft in its ever-varying fantastic forms, in striking contrast to the dark water on which a moment before the eye had rested. Everlastingly is this shifting ice modeling, as it were, in pure, gray marble, and, with nature’s lavish prodigality, strewing around the most glorious statuary, which perishes without any eye having seen it. Wherefore? To what end all this shifting pageant of loveliness? It is governed by the mere caprices of nature, following out those everlasting laws that pay no heed to what we regard as aims and objects.

In front of me towers one pressure ridge after another, with lane after lane between. It was in June the Jeannette was crushed and sank; what if the Fram were to meet her fate here? No, the ice will not get the better of her. Yet if it should, in spite of everything! As I stood gazing around me I remembered it was Midsummer Eve. Far away yonder her masts pointed aloft, half lost to view in the snowy haze. They must, indeed, have stout hearts, those fellows on board that craft. Stout hearts, or else blind faith in a man’s word.

It is all very well that he who has hatched a plan, be it never so wild, should go with it to carry it out; he naturally does his best for the child to which his thoughts have given birth. But they—they had no child to tend, and could, without feeling any yearning balked, have refrained from taking part in an expedition like this. Why should any human being renounce life to be wiped out here?

July 11

At last the southerly wind has returned, so there is an end of drifting south for the present.

Now I am almost longing for the polar night, for the everlasting wonderland of the stars with the spectral northern lights, and the moon sailing through the profound silence. It is like a dream, like a glimpse into the realms of fantasy. There are no forms, no cumbrous reality—only a vision woven of silver and violet ether, rising up from earth and floating out into infinity…But this eternal day, with its oppressive actuality, interests me no longer—does not entice me out of my lair. Life is one incessant hurrying from one task to another; everything must be done and nothing neglected, day after day, week after week; and the working day is long, seldom ending till far over midnight. But through it all runs the same sensation of longing and emptiness, which must not be noted. Ah, but at times there is no holding it aloof, and the hands sink down without will or strength—so weary, so unutterably weary.

Ah! Life’s peace is said to be found by holy men in the desert. Here, indeed, there is desert enough; but peace—of that I know nothing. I suppose it is the holiness that is lacking.

August 4

Lovely weather yesterday and today. Light, fleecy clouds sailing high aloft through the sparkling azure sky—filling one’s soul with longings to soar as high and as free as they. I have just been out on deck this evening; one could almost imagine one’s self at home by the fjord. Saturday evening’s peace seemed to rest on the scene and on one’s soul.

August 5

Brilliant summer weather. I bathe in the sun and dream I am at home either on the high mountains or—heaven knows why—on the fjords of the west coast. The same white fleecy clouds in the clear blue summer sky; heaven arches itself overhead like a perfect dome, there is nothing to bar one’s way, and the soul rises up unfettered beneath it. What matters it that the world below is different—the ice no longer single glittering glaciers but spread out on every hand? Is it not these same fleecy clouds far away in the blue expanse that the eye looks for at home on a bright summer day? Sailing on these, fancy steers its course to the land of wistful longing. And it is just at these glittering glaciers in the distance that we direct our longing gaze. Why should not a summer day be as lovely here? Ah, yes! It is lovely, pure as a dream, without desire, without sin; a poem of clear white sunbeams refracted in the cool crystal blue of the ice. How unutterably delightful does not this world appear to us on some stifling summer day at home?

Read the other entries in this series: Charles Dudley Warner, I.A.R. Wylie, Jennie Carter, Virginia Woolf, Fyodor Dostoevsky, Willa Cather, Thomas Jefferson, Elizabeth Robins Pennell, Izumi Shikibu, Hilda Worthington Smith, Mark Twain, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, and William James.