Self-Portrait, by Jessie Tarbox Beals, 1904. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, gift of Joanna Sturm.

How do you study the Library of Congress’ collection of nearly sixteen million photographs when the objects themselves are out of reach? It’s an esoteric riddle, perhaps, but one that Adrienne Lundgren, a conservator of photographs at the library, was forced to solve when lockdowns began in 2020. She decided that using data science to understand the early history of photography and the context of her institution’s collection might prove interesting, and she was right.

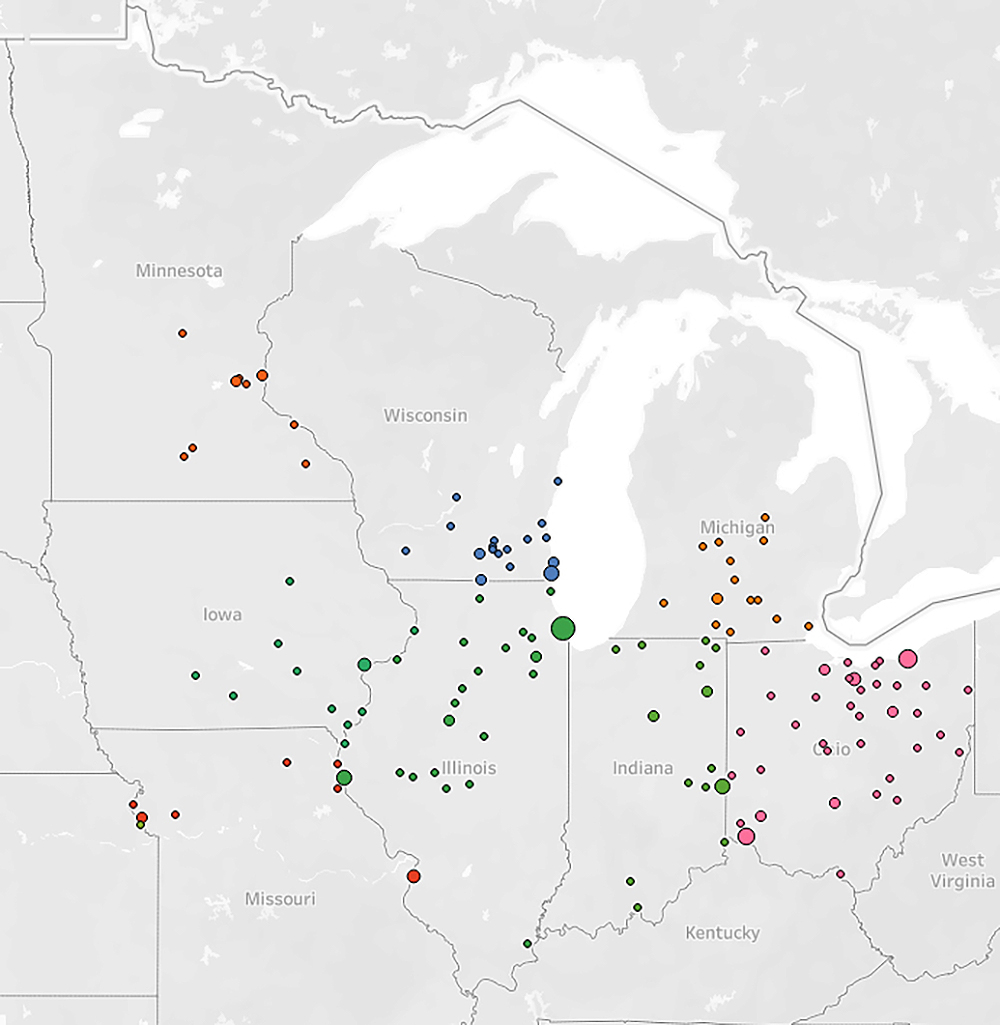

As Lundgren digitized records of the country’s first photographers, an unexpected pattern emerged. During the medium’s first two decades in the United States, the largest concentration of women photographers wasn’t in the Northeast, the country’s most populous region. Women photographers were most active in the Midwest. Between 1840 and 1860 more than half the country’s women photographers were working in just nine states: Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Ohio, and Wisconsin. Lundgren didn’t identify any new photographers in her research; she just looked at the existing records in a new way. “The data was all there,” she told me. “The geographic trends just couldn’t be seen in the original analog format.”

Feminist historians often ask, metaphorically, where were all the women? By this they mean: Where do women appear in history? Where can we find them in the historical record, which rarely includes their names? By taking this question literally, Lundgren has not only found an answer (they were in the Midwest) but also unsettled the early history of photography in the United States, which has long privileged Northeastern cities.

In the Midwest, women made up a little less than 6 percent of the photographers working between 1840 and 1860. This is still a small number, but it is three times more than the percentage of women commercial photographers in the Northeast at the same time. Across the United States, about 3 percent of photographers were women. Beyond asking Where were the women? we ought to begin asking Why were the women there?

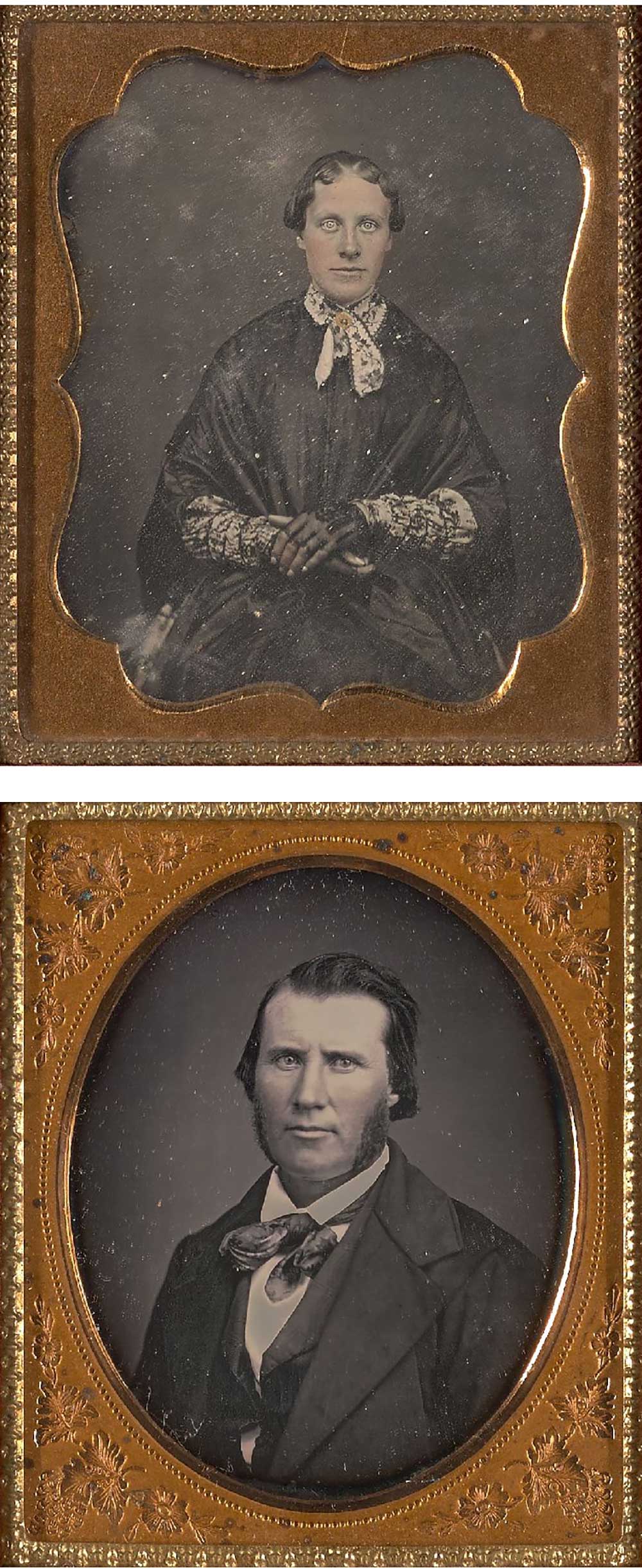

News of a chemical process for recording images from nature was first made public in France in 1839. It was named daguerreotype for its inventor, Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre. (Where were the men? Oh, right there.) American experimenters took up the practice as word of it crossed the Atlantic, and within a few years daguerreotypes dominated portraiture. Their reign lasted until the early 1860s, when the process was replaced by cheaper and more easily reproducible techniques, such as the tintype and the albumen print.

By the end of the 1840s approximately 2,060 photographers had plied the trade in the United States. Some had established studios in major cities. Others made their living as itinerant artists, outfitting wagons and even riverboats as traveling studios. Women were part of this early cohort, albeit in very small numbers—only thirty-three women working in the 1840s have been identified to date. A photographer who went by Mrs. Irwing was a co-owner of a studio in St. Louis, then founded her own studio in a small town in Iowa. A photographer known as Mrs. Davis advertised in 1843 that she had “lately arrived in Houston with a complete daguerreotype apparatus, will be prepared on any day to take likenesses, she will remain in the city but two or three weeks.” Her ad is the first recorded evidence of photography in Texas. Sarah Holcomb, who learned the craft from the early Boston photographer Albert Sands Southworth, set out to establish a studio of her own in New Hampshire; she soon wrote back to her teacher that her chemicals had frozen en route.

The trials faced by these photographers were not unique to their gender. Most of the studios established in the United States during the 1840s lasted only a year or two. After the initial investment in equipment and studio space, photographers encountered challenges in acquiring chemicals and other materials. They also had to convince would-be sitters to have multiple portraits made, lest demand for their services dry up. In the mid-1840s daguerreotypes were still costly. One Philadelphia photographer charged five to six dollars per portrait. This was a sizable outlay, considering that male mill workers earned only ten dollars a month with board and women’s wages were half that or less. Olive Goodwin, a photographer in Minneapolis, tried to accommodate her patrons, advertising that she would accept “all kinds of good grain in exchange for good pictures.”

Photographers also faced the formidable task of simply making an image. The chemical preparations were fickle, influenced by outdoor temperature and humidity, as well as the quality of the chemicals received. Portrait sessions still required bright sunlight, which left the dark winter months a fallow period for many photographers. Reflecting on the early years of her career, Eunice Lockwood, a photographer from Ripon, Wisconsin, recalled “with what ‘fear and trembling’ would we make our first exposure in the morning, and perhaps only a beclouded or obscure shadow of our customer would we obtain, or one well variegated with spots and streaks, and then how we would have to search for the cause and try to overcome it as soon as possible, fully putting into practice the old song, ‘If at first you don’t succeed, try, try again.’ ”

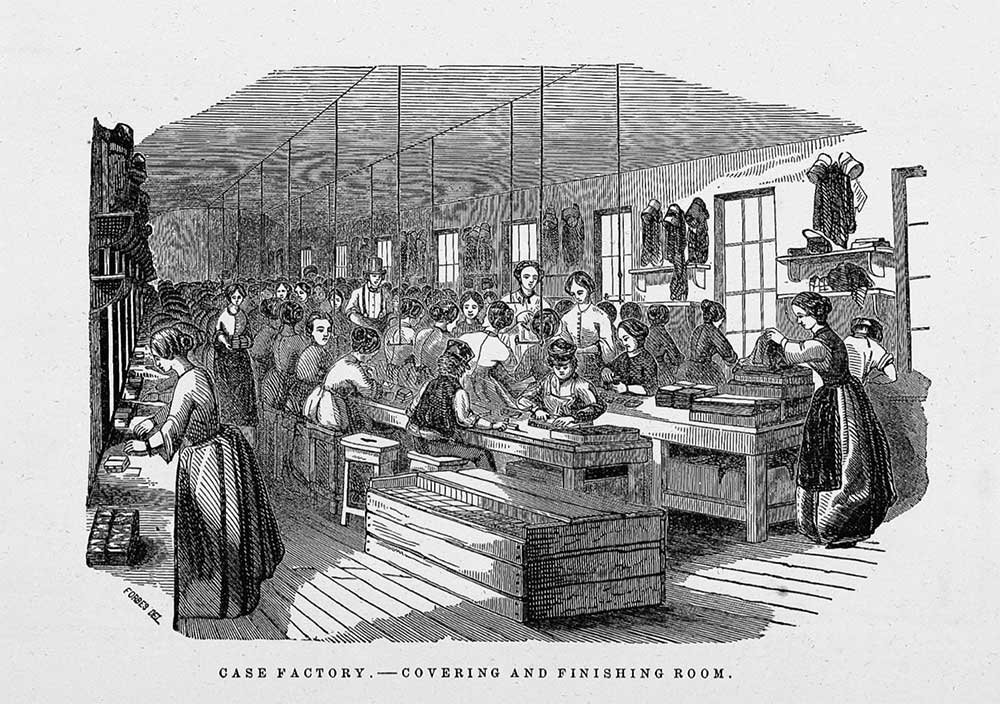

The percentage of women photographers doubled in the 1850s, though, and the total number of photographers who had worked in the U.S. since 1840 surpassed 8,700. (To put it in a Main Street context, there were six times as many barbers identified by the 1850 census as photographers.) The slightly increased incidence of women using the medium did nothing to temper the widespread skepticism regarding their role in the industry, which social reformer Virginia Penny documented in her research on the state of the workforce. In 1862 she published a reference guide of more than five hundred employments for women—compiled from interviews conducted with workers, primarily in New York City, Pennsylvania, and Boston, about conditions in their industries, including the time required to learn the profession, the challenges of the job, and the difference between men’s and women’s wages. According to Penny, women could work in a studio or run their own, make portraits or hand color them, as well as build cameras and craft frames or cases. The men she interviewed, however, insisted that women workers were inferior across the board. The men (unsurprisingly) preferred to maintain sole ownership of the means of production.

A section on photography in Penny’s book The Employments of Women includes correspondence she had with a studio owner who recommended women for hand painting photographs, but Penny noted, “He thinks the taking of photographs not so suitable for women, because it is dirty work; that is, the nitrate of silver that gets on the fingers stains them like indelible ink—a small difficulty, I think, in the way of a woman that has a living to make.”

This argument against women’s participation in photography recurs in the period literature, especially in the trade press. Even an otherwise sympathetic author wrote in 1873, “Though it is admitted that women can do everything photographic, yet there are certain portions where ill-smelling chemicals and dress-disfiguring solutions are used that are better conducted by the rougher sex.” The chemical stains were considered unsightly, but they also seemed to stand in for a host of character traits that appeared like invisible ink when men imagined women in photographic studios. When Penny’s interviewee suggests that “men are superior in patience,” she raises an editorial eyebrow and inserts a question mark in parentheses.

Penny let women defend themselves against these charges in print for the first time—and explain the true difficulties of the job from their perspective.

The principal discomforts of the business are the heat to which we are exposed in summer (being usually and necessarily near the roof), the smell of chemicals (which do not unpleasantly affect anyone), and the soiling of clothing, which is more unavoidable with women.

The chemical stains weren’t more disagreeable to women; stains were simply more likely because of the clothing women were expected to wear.

Penny’s research also reveals the way that the Victorian doctrine of “separate spheres,” or the separation of the sexes, was used to justify wage discrimination. One studio owner admitted, “Women are sometimes employed in the reception room to receive ladies—occasionally, in the operating room [the studio]. They receive from $3 to $8, according to capacity and address. Men generally command better prices, because they can sometimes perform labor out of a woman’s sphere, such as unpacking goods, carrying packages, and other jobs not suitable for women.” A woman studio owner explained that she had hired a helper for this kind of rote labor, while she devoted herself to making portraits and managing the business.

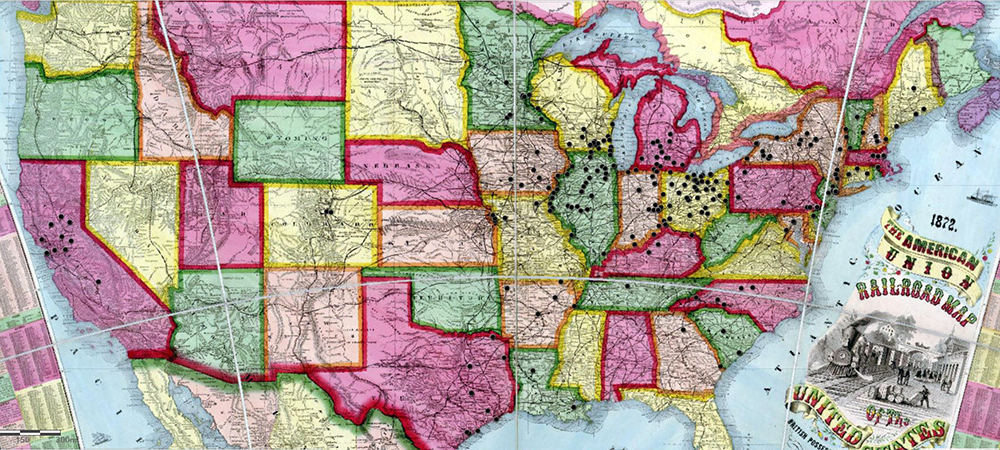

Especially in the entrenched social hierarchies of the Northeast, these gendered expectations seem to have negatively affected the number of women in the profession. It didn’t have to be this way. Telegraphy, another new technology that became popular in the 1840s, appeared gender neutral in all ways except pay. Thomas Jepsen, a historian of the telegraph, writes that “by 1873 women were so commonly employed as depot operators as to evoke little or no comment.” He suggests that the acceptance of women telegraph operators may have been driven by necessity, particularly as the telegraph expanded into rural areas. The same may have been true of photography in the Midwest.

The description “the Midwest” would have been unknown to the people who lived there in the middle of the nineteenth century. Settlers in the region thought of it as the West or the Old Northwest, formerly the Northwest Territory. The area appropriated from its indigenous inhabitants was divided into five states: Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, and Wisconsin. For people who had moved from population centers in the East, this was the West. The nationally acclaimed Black photographer James Presley Ball even called his Cincinnati studio “Ball’s Great Daguerrean Gallery of the West.” It wasn’t until the 1890s that the designation of “Middle West” was applied to the region, which then expanded to include seven more states: Iowa, Kansas, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, and North and South Dakota. The historian Frederick Jackson Turner theorized that it was the region’s distance from the Eastern establishment that made the culture of the advancing Western border states distinctive. Promoting what is referred to today as the frontier thesis, Turner argued that the region’s culture was characterized by “freshness, and confidence, and scorn of older society, impatience of its restraints and its ideas, and indifference to its lessons.” Such relative freedom from social strictures, at least for settler colonialist inhabitants, seems to have benefited white women entrepreneurs.

In 1870, the first year the U.S. Census Bureau collected women’s occupational data, 13 percent of working-age women in the Midwest were wage earners compared with a little under 6 percent of women in the Northeast. The textile mills of the Northeast were an important engine of women’s economic independence in the early nineteenth century, but they allowed little independence on the job itself. In the Midwest, which industrialized later, women who wanted or needed to work were more likely to work for themselves. Lucy Eldersveld Murphy, a historian of women’s labor, estimates that 10 percent of working women in the Midwest owned their own businesses, and the majority of these were in new towns or small cities.

Women photographers were also more likely to work in small towns than in large cities. Some started their own businesses, such as Lucy Jane Bolt Easton of St. Charles, Minnesota, and Jennie L. Motes of Lebanon, Ohio. Some unmarried women partnered with their sisters. Others, like Mrs. L. Holbrook of Weston, Missouri, taught their daughters the business. Many worked in partnership with their husbands and took over the studio after being widowed. Catherine McCormick Reed, who ran one of the longest-lasting studios operated by a woman, began business in 1848 in Quincy, Illinois, in partnership with her husband. After his death a decade later, she opened a new studio, the Excelsior Gallery, just blocks from her home. Reed appealed to her customers’ sympathies. One of her advertisements read: “Patronize the widow, and thus give bread and education to the orphan.” In the early 1860s she opened two more galleries further along the Mississippi River, in Missouri. Reed maintained her Quincy studio until 1888, just two years before her death at age eighty-two.

Ohio, the first in the region to attain statehood, was home to the largest number of women photographers by 1860. The state was famously progressive during these years, a center of abolitionist and suffragist organizing. Although later press would sometimes identify James Presley Ball as the only Black photographer in the region, there were at least twenty other Black men who were working as daguerreotypists in the United States between 1840 and 1860, including eight in the Midwest. Ball collaborated with his brother and brother-in-law to establish other studios throughout the region, but there is as yet no evidence of Black women photographers working for Ball or elsewhere during the Daguerreian era.

Turner’s thesis, which posited the frontier as “a new field of opportunity,” applied unequally, at best, to people who lived in the region. The old structural barriers remained, from racist money-lending practices to sweeping “Black Laws,” which restricted Black settlement and enfranchisement in midwestern states and elsewhere. At worst, Turner’s ideas were taken as further justification for the brutality of territorial expansionism and American imperialism. By the time Turner was writing in the late nineteenth century, white Americans regarded indigenous Americans as a “vanishing race,” as the title of one contemporary book of photographs put it. Although there was a huge market for photographs of Native Americans, these pictures were made by non-Native photographers, at least until the turn of the century when photographers such as Benjamin A. Haldane (Tsimshian) started studios in their communities or acquired handheld cameras, as did Jennie Ross Cobb (Aniyunwiya [Cherokee]) and Bertha Felix Campigli (Coast Miwok). As the men interviewed by Virginia Penny revealed, controlling the means of production controls not only the workers directly involved in that system of production but also the way their stories are told for generations hence.

Economists studying the Covid-19 pandemic have also asked: Where are the women? In 2020 the United States suffered its first decline in women workers in fifty years. Researchers call it a “she-cession,” or a recession that disproportionately affects women workers. Women of color have been especially affected, representing more than half the workers in the service sector—which includes many of the jobs deemed “essential” during the height of the pandemic—while also facing increased caregiving demands at home. By February 2021 women’s participation in the labor force ebbed to its lowest point since 1988.

These losses are no longer invisible in the historical record. The Census Bureau found that in January 2021 ten million U.S. mothers living with school-age children were not working in wage-earning jobs, a figure that had increased by 1.4 million in just twelve months. This statistic equals one-third of all mothers with school-age children living at home, compared to just one-tenth of fathers in the same category. From the gender pay gap to the unpaid domestic labor that weighs more heavily on women, American society still implicitly enforces a doctrine of separate spheres.

To accommodate these social inequalities, women workers have historically needed to be more nimble, changing jobs frequently or working close to home, like Margaret J. Newton, whose studio was located over her husband’s dentistry office in Richmond, Indiana. Lucretia A. Gillett moved with her parents from New York to Saline, Michigan, around 1850; she lived with them for the rest of her life and worked as the town’s only photographer for more than thirty years.

Photography in the twenty-first century remains a flexible employment opportunity for women. This malleability is not without social stigma. In the early days of social media, self-employed women photographers were saddled with yet another burden: the derisive nickname of “momtographers.” Urban Dictionary’s top definition for the term: “Usually a stay-at-home mom who buys a camera from Best Buy, teaches herself the basics of Photoshop and starts her own ‘photography company.’ ” Were I Virginia Penny, I would insert a battery of question marks after this lazy writer’s scare quotes. Instead I’ll ask: Where are the men? Oh, this definition was written by one. He calls himself “MarketingMan.”

The history of photography has similarly dismissed the work produced by early women photographers. Portraits of unnamed sitters made by unknown photographers have largely been ignored by the collecting market, which instead prizes images that are unique or deemed historically significant. In order to find the products of photographers who were not valued by the establishment, we have to look beyond the establishment’s most lasting institutions. Where are the women? Their photographs are disproportionately held by local historical societies and libraries rather than large art museums. Their photographs are found in family albums more often than auction catalogues. Turning over a vintage photograph and finding a woman’s name should also inspire us to turn over lingering prejudices about who does work today and how we value their labor, whether it’s close to home or in the public sphere.