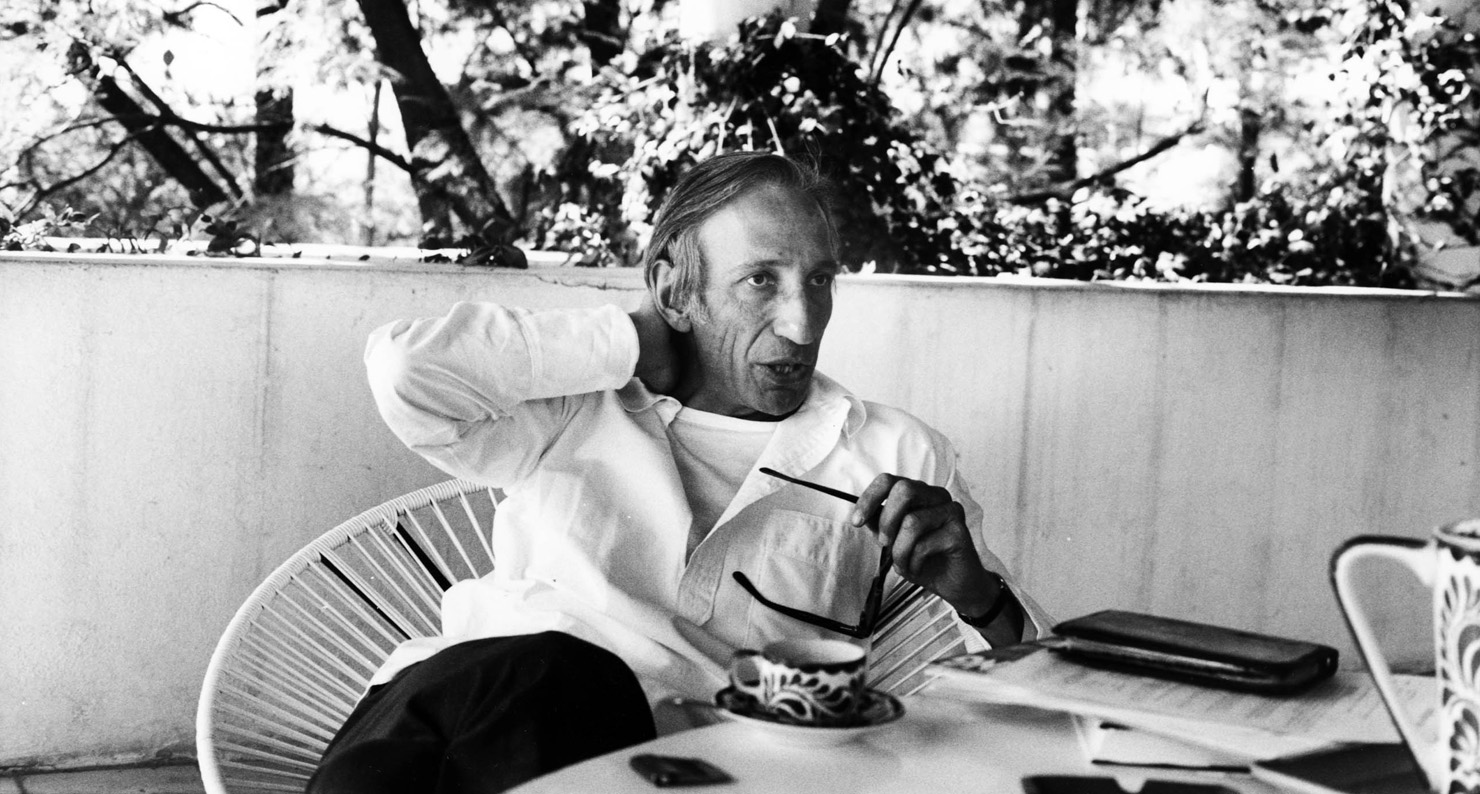

Ivan Illich at home, 1976. Photograph by Bernard Diederich. © The LIFE Images Collection/Getty Images.

It has become a rite of passage for privileged young Americans to spend a year abroad doing service projects—installing toilets, teaching English, and purveying other rudiments of progress. For many of those embarking on such journeys, there is a further rite of passage: reading the text of a 1968 speech by Monsignor Ivan Illich, a Catholic priest. Illich’s speech usually appears under the title “To Hell with Good Intentions,” after one of its most telling passages. Illich’s argument was an assault on the idea that affluent Americans have any help worth offering poor people abroad—in this case, in Mexico. Attempts to help, said Illich, do more harm than good.

Illich delivered his address in Chicago at a regional meeting of the Conference on Interamerican Student Projects, which was populated by organizers from groups that sent young people abroad for service. They represented the spirit of benevolent expansionism that President Kennedy had promoted at the start of the decade through programs like the Peace Corps and, for Latin America in particular, the Alliance for Progress.

At the time, too, Illich’s Catholic Church was joining in the excitement. From the pope on down, there was an initiative underway for sending 40,000 foot soldiers—a full 10 percent of then-plentiful U.S. priests and nuns, along with lay volunteers—to serve their poorer and less well-catechized neighbors in Latin America. Missionaries would carry out charitable works while lovingly upgrading native religiosity with European doctrines and devotions. Such missionizing aligned neatly with the imperatives of the Cold War—a holy complement to the continuing dirty wars against godless communism.

Before his prepared remarks, Illich began by lamenting the “hypocrisy” he had observed at the conference among those now seated before him. He was impressed, he said, that the young people in the audience already knew, based on past expeditions, that their efforts would probably not be especially helpful, and that most well-intended volunteer activities result in nothing like their promises and ambitions for those they purport to serve. And yet his hearers were still planning to send more gringos south.

“I did not come here to argue,” Illich went on to say. “I am here to tell you, if possible to convince you, and hopefully, to stop you, from pretentiously imposing yourselves on Mexicans.”

This rebuke—to the credit of the meeting’s planners—could not have been entirely unexpected. At the time Illich was among the Catholic Church’s most brilliant and irascible clergymen. He was the son of a Jewish mother and a Croatian father, an ancestry that compelled him to leave his home in Austria soon after the rise of Nazism. He studied in Rome for a career at the Vatican, but afterward moved to New York City and took a poor Puerto Rican parish in Washington Heights. His success there made him the church’s go-to man for tutoring American priests assigned to Spanish-speaking parishes. By the mid-1950s, he’d been dispatched to Puerto Rico to run an institute for that purpose.

At first, Illich held out hope for the church’s expansion of the missionary project. A 1956 speech, “Missionary Poverty,” described the vocation of the missionary as a worthy exercise in self-abnegation. A missionary “has to become indifferent to the cultural values of his home,” Illich said. “He has to become very poor in a very deep sense.” Even this modest, ascetic kind of optimism faded, however. Clashes with the Irish American bishops who governed the church in Puerto Rico caused him to flee and start a more radical teaching center in Cuernavaca, Mexico, which would eventually become the Centro Intercultural de Documentación.

According to an unpublished memoir by Father Paul Mayer, who knew Illich in New York and Cuernavaca, “Ivan believed that U.S. missionaries would (even unwittingly) be neo-colonialist emissaries and bring North American values, theology, ideology, and politics to the people of Latin America under the guise of preaching the Gospel.” In the last years of his life, Mayer—also a Jewish refugee from Nazism who became a troublesome Catholic priest—remembered Illich’s presence in his Cuernavaca seminars. “Although a good-hearted man by temperament, he did not hesitate to resort to ruthlessness in these dialogues,” he wrote.

Illich’s clash with Catholic missionary policy is the subject of a new book, The Prophet of Cuernavaca: Ivan Illich and the Crisis of the West by historian Todd Hartch. It describes the process by which Illich leveraged his reputation as the Latin American church’s foremost educator of linguistic and cultural fluency for a kamikaze mission against the very effort he was supposed to be serving. In part thanks to his writing and teaching at Cuernavaca, the missionary initiative fell far short of its ambitions. His attacks on the missionary project came at a cost; by the end of the 1960s, his relationship with the Vatican had soured to the point that he renounced the public office of clergyman, even while remaining—privately, spiritually, and canonically—a priest.

Hartch faults Illich for not giving Catholic missionaries more of a chance to learn cultural sensitivity, to do real good abroad, and to bring their lessons home. He also challenges Illich for opposing a policy promulgated by the church, to which he always claimed allegiance. “Even the trickle of missionaries who did serve in Latin America has provided its share of critics of American culture, politics, and religion,” Hartch writes. “Imagine if there were a thousand more such people active in American life today.”

Illich, however, was not a patient or liberal reformer, and he never sought to be. Alongside his battles against missionizing, he published widely discussed tracts that took aim at the period’s favorite manifestations of progress—such as Deschooling Society, against compulsory education, and Medical Nemesis, against institutional medicine. His polemics displayed little interest in merely “moving the needle,” as philanthropists are apt to say nowadays. He refused to compromise with whatever appeared newer, bigger, richer, and better, and he sought to smash these in order that smaller and older forms might grow in the cracks. As a passionate educator and disciplined yoga practitioner, Illich was not opposed to structured learning or physical health as such; what distressed him was when the institutions meant to provide such things become so powerful that they deny people’s freedom to define what education means, or what health consists of, for themselves. So also with the church. A church for the poor, he thought, is no longer that when its missionaries are also ambassadors of American affluence.

“By becoming an ‘official’ agency of one kind of progress,” Illich wrote in 1967, “the Church ceases to speak for the underdog. We must acknowledge that missioners can be pawns in a world ideological struggle and that it is blasphemous to use the Gospel to prop up any social or political system.”

Illich’s outlook, among other neglected and worthy tendencies in the Catholic past, finds fresh vindication in the era of Pope Francis. Illich made efforts to cultivate theologies grown out of the distinct experience of Latin American Catholicism. In 1964, for instance, he organized a meeting in Brazil among theologians who would soon go on to become the framers of liberation theology. Notwithstanding a recent spate of claims in the conservative Catholic press that the movement was an invention of the KGB, this was a theology of Latin America, by Latin Americans. Francis, the first Latin American pope, recognizes liberation theology’s best impulses as such; one of those who attended Illich’s meeting in Brazil, Gustavo Gutiérrez, has recently been invited to speak at the Vatican after many years of disgrace. Since his tenure as archbishop of Buenos Aires, the pope has insisted the church should learn from the devotional practices of the marginalized, not try to stamp them out.

The usual logic of philanthropy assumes that a person who has accumulated wealth and expertise is qualified to know what is best for others. Who could be better equipped than Mark Zuckerberg to decide how poor people use the Internet? Or Bill Clinton to promote democracy abroad? Sending affluent teenagers to developing countries helps accustom the givers and recipients alike to the resulting unidirectional flow of aid. This habit, and its corollaries, Illich sought to break.

Many of the Illich’s followers today are more secular than ostensibly Catholic. I once met a Mexican abortion provider, for instance, who cited him as an influence; an arts organization in Puerto Rico, Beta-Local, runs a school named after him. But Illich’s contempt toward the development agenda of the wealthy represents, it seems, an essentially Christian kind of faith that the meek should inherit the earth—and that we have more to learn from them than from the rich.

“Come to look, come to climb our mountains, to enjoy our flowers,” he said at the end of his 1968 speech in Chicago. “Come to study. But do not come to help.”