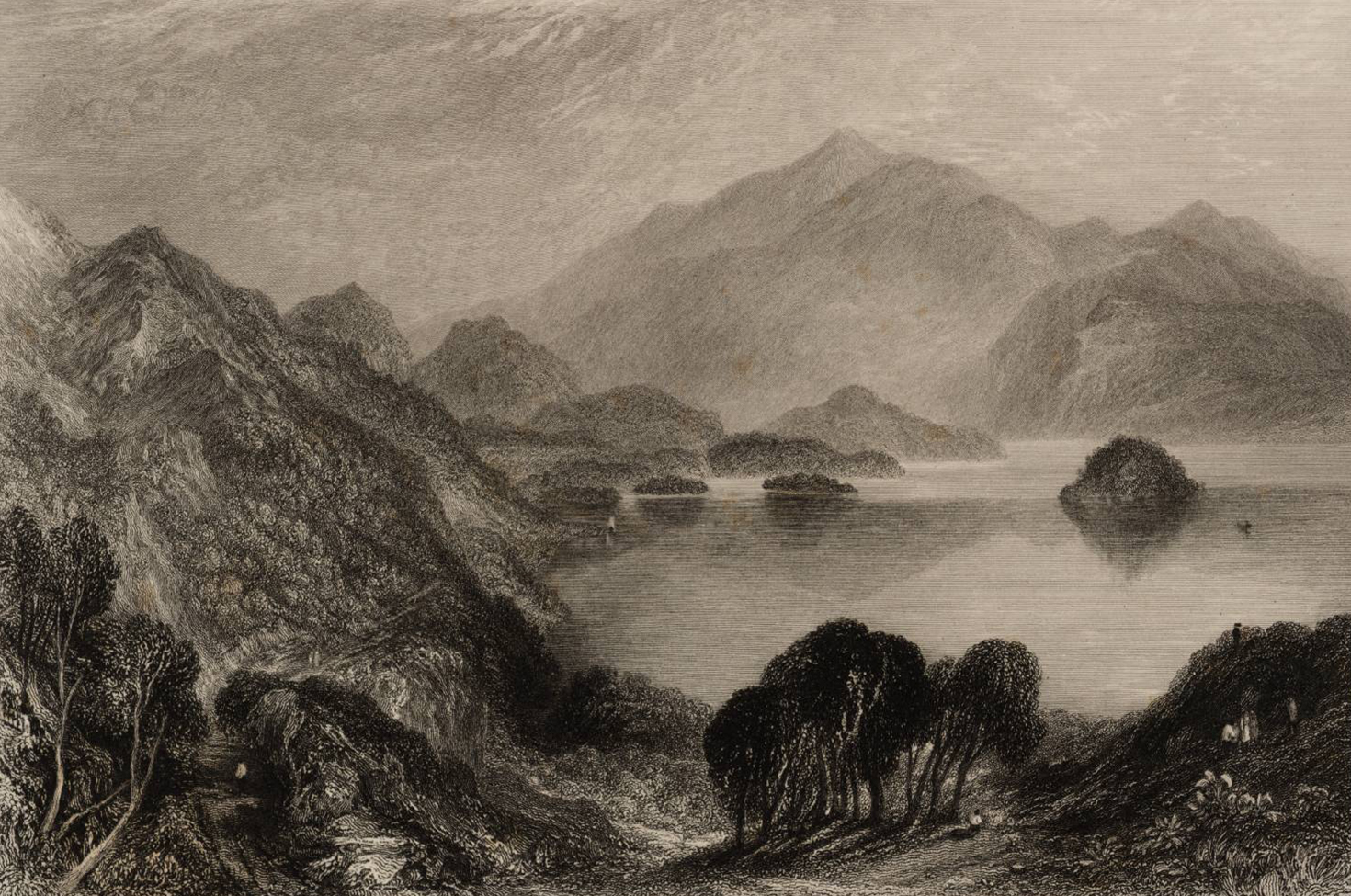

Loch Katrine, after Joseph M.W. Turner, 1834. Photograph © Tate (CC-BY-NC-ND 3.0).

Arriving in Edinburgh on April 21, 1822, aboard the Leith Smack Superb, Sarah Stoddart Hazlitt stepped onto the docks toward a most uncertain future. She had journeyed for seven days up the British east coast from the Thames in order to be divorced by her husband of fourteen years, the essayist William Hazlitt, who had become infatuated with the teenage daughter of the landlady of his lodging house in London. Lacking the financial resources or the social influence to obtain a divorce by Act of Parliament, Hazlitt hatched a plan to be “caught” by his wife in the arms of a prostitute in Edinburgh, where their marriage might be dissolved under Scottish law much more quickly, and more affordably, than in England. Over the next three months, while she lived in Edinburgh, Sarah would be bullied by her husband’s friends, commit perjury, and become ill by guilt and anxiety at her complicity in his degrading schemes. She managed the complex emotions that swirled during this period by keeping a terse diary in which she documented both the circumstances of her divorce and the miles and miles of walking she undertook when she had the chance to steal away. On foot, she was able to enjoy something approaching freedom as she rambled across Edinburgh and its surrounds, in contrast to the suffocation of lawyers’ offices and the distressing prospect of an anxious future as a single woman. Walking was to prove an important antidote to the debilitating emotional and physical effects of her husband’s coercive behavior.

During her first few weeks in Edinburgh, Sarah’s time was split between legal matters and exploring the city. Communication with William was via her solicitor or a go-between, the better to preserve the entirely false appearance that their simultaneous presence in Edinburgh was coincidental. The terms of their arrangement were that Hazlitt would cover his wife’s costs during her stay in Edinburgh, and in return she would swear—falsely—an oath of calumny asserting that she had no prior knowledge of his activities, thereby enabling the divorce to proceed. During the many delays in obtaining solicitors or legal documents, or just getting a straight answer to a simple question, Sarah walked across Edinburgh and some distance beyond, exploring well-known tourist haunts (Calton Hill, Arthur’s Seat) and out-of-the-way places (Lasswade, Rosslyn Glen) with equal enthusiasm. On these excursions, she usually walked alone, typically for hours and miles at a time.

In the middle of May William left Edinburgh for a short while, first to lecture at Anderson’s College in Glasgow, then to walk in the southern Highlands. His absence and the consequent pause in the legal proceedings enabled his wife also to take her leave of Edinburgh for a while: on May 14 she returned to Leith to board another ship, this time heading north and west along the Forth to Stirling. With little money in her pocket and without remark in her journal, Sarah was about to embark on an extraordinary adventure.

By the 1820s it was reasonably common for tourists to be found traveling through the southernmost Highlands, especially following the publication of the numerous works by Sir Walter Scott set in the area: the popularity of his writing drew people in increasingly significant numbers to the lochs and hills he so lovingly described. It was almost unheard of, though, for a foreign woman to be found walking alone, yet that’s what Sarah did. Without a companion and only occasionally with a guide, she set off from Stirling on a week’s tour of the southern Highlands that took in many of the famous sights (the Falls of Leny, Loch Katrine, the Falls of Clyde) but veered considerably at times from the standard tourist routes. During this period she covered distances of between twenty and thirty miles each day and endured at various points considerable physical danger, typically with courage and good cheer. In the course of her tour, she walked 180 miles back to Edinburgh. She relished the chance encounters and happenstances that occurred along the way and found, after the hardship of walking, significant physical pleasure in the simplest acts—eating, washing, sleeping.

On May 13, with no preamble at all in the journal to indicate she was planning a voyage of any length, Sarah abruptly records that she sailed, entirely alone, from Newhaven port for Stirling, several miles up the Forth. From there, she set off on foot, and two days into her journey she had walked as far as Loch Katrine in the Trossachs hills, made famous by Scott’s 1810 poem The Lady of the Lake. Nestled in a bowl below the grand hills of Ben Ledi and Ben Lomond, the loch’s singular situation enchanted the solitary walker, who hired a boatman to take her all along its “different and beautiful windings.” Her tour of the loch’s sinuous banks complete, she disembarked and set off on foot for the pass between Loch Katrine and Loch Lomond that would take her south toward her night’s accommodation in Luss, on the western bank of Loch Lomond. The land between the lochs, though, was at this time remote and infrequently traveled, and with the weather closing in, she found herself in some danger. In her journal for that day, May 16, 1822, she recorded “in crossing the most dreary, swampy, and pathless part” of the moorland beyond Loch Katrine: “A heavy storm came on, there was not the least shelter, and the heat in climbing such an ascent, together, with the fear of losing myself in such a lonely place almost overcame me.” Sarah would have had no map or compass to help her.

What could have been a fatal disaster became in the end a grand adventure that thrilled Sarah. She exulted in her diary, upon her arrival in Luss “about ten o’clock at night,” at how she had been “quite enraptured with my walk, and the great variety of uncommonly beautiful scenery I had passed through in the course of the day.”

Once at Luss, Sarah picked up again the popular tourist route between Glasgow and the Trossachs, though it is unlikely that many tourists would have endured the physical hardships that she experienced over the remaining days of her expedition. Nor is it likely that many tourists would have responded to those hardships as she did, with acceptance, perhaps even relish. The morning after her journey across the boggy flanks of Ben Lomond, Sarah walked to Dumbarton, fifteen miles away.

On the boat from there to Glasgow, she complained of having “now such a violent cold in my head that I could hardly breathe or look up, and my limbs ached dreadfully, particularly about my right knee, which I had wrenched in getting out of the boat, at Inversnaid ferry.” However, this did not stop her from exploring Dumbarton the next day, nor from walking the seventeen miles from Lanark to West Calder the day after that.

At Lanark Sarah enjoyed the beauties of the Falls of Clyde, a series of cascades sought out by tourists from Dorothy Wordsworth to John Constable. She also took in the curiosities of Robert Owens’ New Lanark, a model settlement established alongside the banks of the Clyde, where its innovative owner experimented with welfare programs for his workers. From the steep-sided gorge of the Clyde, Sarah set off on her most grueling day’s walking:

After leaving all these beautiful scenes, I had one of the most desolate and forlorn walks that can be imagined. Immediately on quitting Lanark I entered on a wide, black boggy moor, which lasted seventeen miles, with a broiling sun, and not a tree, or the least shade all the way. I sat down several times on the ground from mere inability to proceed, but was afraid to rest many minutes at a time, as I was so stiff I could scarcely move afterwards.

The fragility of her position is evident here, as it was in her account of losing her way from Loch Katrine; as a lone walker Sarah is more vulnerable to danger, with no one to aid her or, it would seem, anyone to raise the alarm should she not return. But the anxiety expressed in this entry does not arise from the sources typically attributed to women’s walking—sexual harassment or assault—but from dangers familiar to any solitary walker of either gender, then or now.

There is no evidence of Sarah being aware that her walking might place her in an unusually vulnerable position or that it might make her seem singular. Instead, what is apparent is a keen awareness of the physical realities and necessities of accomplishing a punishing walk like this. While her experience is not a pleasant one—she describes herself as being that evening so “utterly exhausted with heat and fatigue,” and her feet “so swollen and painful that it was many hours after I got to bed before I could sleep”—she has actively chosen to suffer, rather than had suffering inflicted upon her.

The difficulty of the walks mattered to Sarah. At the end of her journey around the Forth and Clyde valleys, she summed up the distance covered in a meticulously neat table:

number of miles each day

Monday 13th May: 4

Tuesday 14: 20

Wednesday 15th: 32

Thursday 16th: 27

Friday 17th: 21

Saturday 18: 21

Sunday 19: 28

Monday 20th: 17

170

This reckoning includes seventeen miles traveled from West Calder to Edinburgh on the morning of May 20, a walk embarked upon the day after she had been unable to sleep because of the pain and swelling in her feet. She notes that “it was with some pain and difficulty that I finished my jaunt,” but the significance of the walk is measured in miles: miles over bleak and difficult terrain; miles of thirst and heat and danger; and miles walked out because she wanted to walk them, and because she physically could. Hardship during her walks was, for Sarah, cathartic and refreshing, and empowering, too: for the most part, she could retain control over how much pain she suffered and when she relieved it—in contrast to the limitless distress of her divorce proceedings.

The return to business in Edinburgh was abrupt. Within days, the feelings of elation and well-being had dissipated in the confusion of the legal proceedings, and Sarah’s body reacted quickly and painfully. “Very nervous and poorly today,” she noted just four days after her exultant return.

Her decision a week later, on May 31, 1822, to embark on a second walking tour must therefore have been a profound relief to body and mind. This time she was intent on exploring further east in the Highlands.

At times Sarah attracted attention as a solitary woman on foot in the Highlands, but it was always kindly and solicitous—she writes that the she was able to “walk all through the country without molestation or insult” among people “universally civil and obliging.” Walking alone was when she experienced the greatest pleasure, and when her walking held most meaning.

I had still other mountains to climb in succession; a most laborious road, and I should have been utterly exhausted with fatigue and heat had I not found some mountain springs in my way; and lay down and bathed my face, and drank to allay the parching thirst. I was but clumsy at it at first, but I soon managed so as to drink very well, and was refreshed, and was thankful that God had provided water in the stony rock. These walks always make me more religious and more happy, more sensibly alive to the benevolence and love of the Creator than any books or church. His care and kindness seems shown in all his works. Nothing here seems contradictory.

She again writes of significant physical discomfort, but in this entry, her suffering is elevated into an experience of profound personal, even spiritual, meaning. Walking becomes here the medium of creation itself. She does not feel more religious but is more religious because she exists as a walker: pedestrianism for Sarah Stoddart Hazlitt is fundamental to her experience of self and her understanding of her place in the world.

Reprinted with permission from Wanderers: A History of Women Walking by Kerri Andrews, published by Reaktion Books Ltd. Copyright © 2020 by Kerri Andrews. All rights reserved.