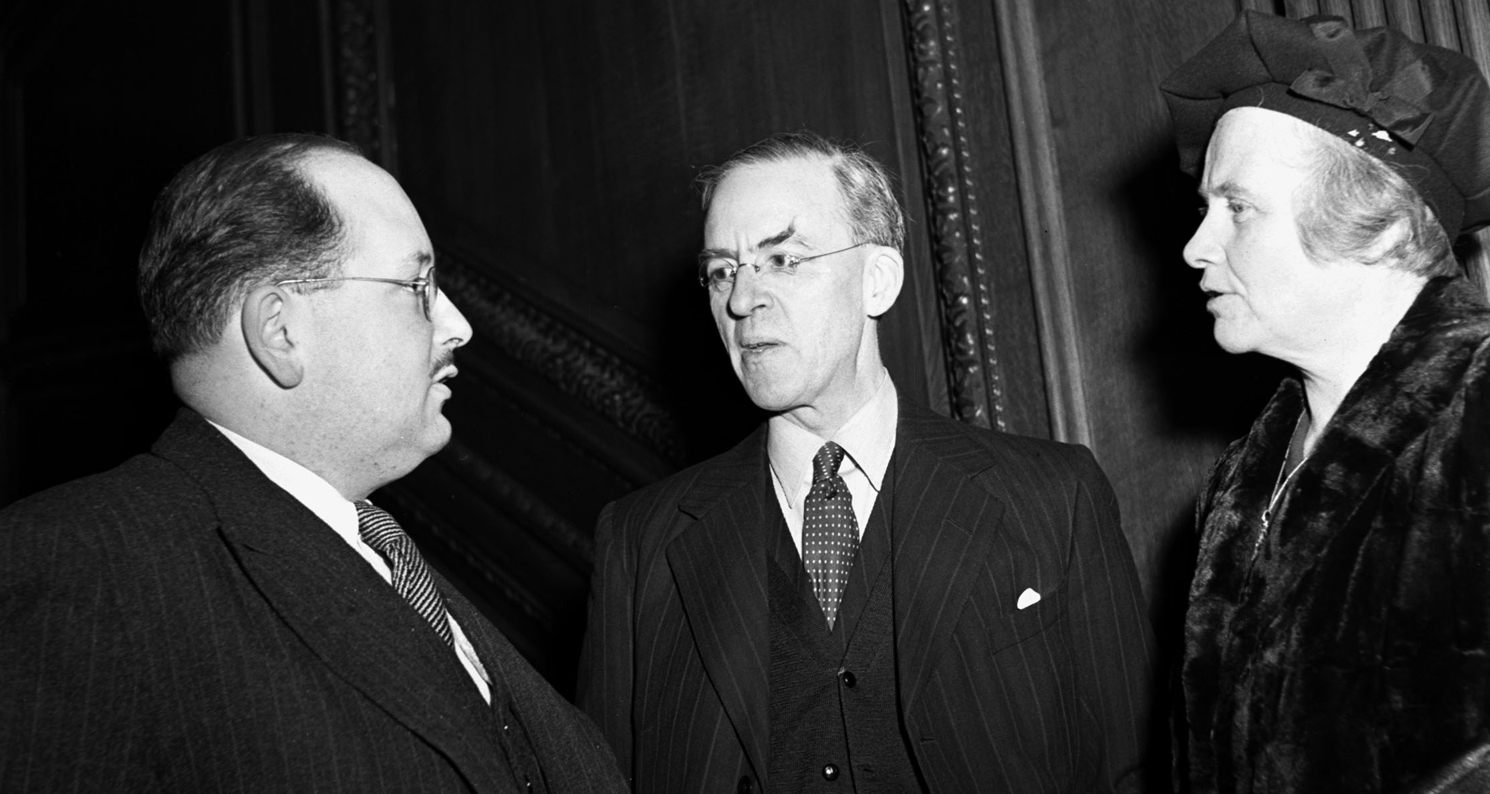

Hans-Peter Smolka, left, with Sir Stafford Cripps and Lady Cripps at a 1944 event in London honoring the twenty-sixth anniversary of the Red Army. Courtesy of Getty Images.

Audio brought to you by Curio, a Lapham’s Quarterly partner

He gave me my first watch, my first bicycle, and my first pair of skis. He was my godfather, rich and generous, and in my naive, uncritical childhood I adored him. When I was growing up in London, he lived around the corner from us in Hampstead and came almost daily for lunch and tea, a bulky, buccaneering mercurial figure with a voice that boomed.

He was my father’s closest friend. In 1947 he decamped with his wife and two sons back to Vienna, the city he had fled—like my dad—a dozen years before.

His name was Hans-Peter Smolka, and he was a Soviet spy.

A mysterious, shadowy figure, he is less glamorous in British eyes than the other Cold War spies: Guy Burgess and Donald Maclean, both of whom defected to Moscow in 1951; Harold “Kim” Philby, the so-called Third Man, known as “the spy of the century” who was exfiltrated from Beirut in a Soviet freighter in 1963; Sir Anthony Blunt, eminent art historian and keeper of the royal pictures, exposed as the Fourth Man in the late 1970s; and John Cairncross, who betrayed atomic secrets to the Soviets in the 1940s and was finally confirmed as the Fifth Man in 1990.

These were the canonical five. Smolka was the sixth.

As a dubious émigré—albeit one awarded a British passport and a postwar OBE—he was not “one of us,” not clubbable, and his acts of treason and personal betrayal thus less shocking. He was nevertheless on a par with the Cambridge spies in significance. When he died in 1980, a distinguished Viennese millionaire with his reputation still intact, the obituaries—one written by his childhood chum Bruno Kreisky, the Austrian chancellor—were fulsome. It took a decade—and the mining of the KGB files after the Soviet collapse in the early 1990s—for the lurid story of his treachery to emerge.

He and Philby hung out in wartime London, an improbable but inseparable pair. At parties they would signal each other with an unlit cigarette indicating one or the other had a morsel of intelligence to impart. By then the Englishman had penetrated MI6 on behalf of Moscow, while the Austrian had gained extraordinary access to the circles surrounding Churchill. As a foot soldier fighting fascism for the Soviet cause, Smolka was under the control of Anatoly Gorsky, the same official rezident at the Russian spy mission in London who controlled Philby, a prized asset. Back at HQ—the NKVD building known as the Lubyanka in Dzerzhinsky Square—Smolka rapidly earned a reputation as a highly valued, trustworthy, and resourceful “deep penetration agent,” one of Stalin’s best. Moscow Central code-named him ABO.

My father died in 1986 before the news broke. I am not sure if he knew.

He and Smolka had met in Vienna as children, assimilated deracinated Jews descended from pious Bohemian rabbis. Smolka, two years younger than my father and the son of a successful businessman, grew up in relative comfort, despite widespread starvation and ruinous hyperinflation in Vienna following a lost war. Their world was the rickety Austrian Republic, the German-speaking remnant of the defeated Hapsburg empire that consisted geopolitically of a giant progressive Viennese head placed by the victorious, vengeful allies on the shoulders of a tiny reactionary Catholic body, a doomed and resentful rump racked by revanchism.

As teenagers Smolka and my father were naive lefties. In the 1930s the political situation in Vienna careered toward confrontation between the clerical Austro-fascists and the metropolitan Marxists. They moved further to the left and in the early 1930s started a magazine, The New Youth, edited and published out of my widowed grandmother’s kitchen and fueled by Smolka family cash. It lasted four issues.

Enter Kim Philby in the fall of 1933.

Fresh down from Cambridge, Harold “Kim” Philby, an upper-class Englishman with a famously rebellious anti-establishment father, showed up in Vienna hoping to witness the coming showdown. Already a student Marxist, he had gone there at the suggestion of his pro-Communist tutor at Cambridge. He arrived in the Austrian capital armed with contacts at a moment when the proto-fascist chancellor Engelbert Dolfuss had suspended the constitution and outlawed strikes. The Viennese cafés were rife with rumors of impending blood. On day one Philby met the young Jewish firebrand Alice “Litzi” Kohlman and was smitten. Just twenty-three but already a hardened revolutionary working for the Moscow-led European underground who was in regular touch with Soviet intelligence, she happened to be a good friend of Smolka’s—which is how the two men met.

Two weeks later the storm broke. Dolfuss called in the army. He shelled worker’s apartments with artillery, killing hundreds, attacked and trashed trade union centers, and rounded up and hanged left leaders. During this two-week civil war, the locals Smolka and Litzi, together with their new comrade from England, Kim Philby, worked tirelessly—at significant risk to their lives—smuggling activists out of Vienna, many through the sewers. Sharing risk forges bonds.

Some sources say it was then and there that Smolka turned from a wishy-washy social democrat like my father into a dedicated Communist. Parliamentary democracy had failed both in Germany and Austria, he thought, and the Soviet Union was the last, best hope to prevent a Nazi victory—with all that would imply for a Jew.

Others believe Smolka was already an NKVD “illegal” by then, recruited by the Hungarian-born international super agent and former Catholic priest Teodor Maly, who later fingered Philby as a promising NKVD prospect. Maly sought young, ideological “deep penetration agents” who would go on to rise through the ranks of the British establishment—in particular the intelligence world—and remain willing to betray their friends and country for Moscow’s cause.

As the police dragnet closed in on Litzi, Philby married her in Vienna Town Hall to save her life: his British passport offered her protection. Then Mr. and Mrs. Philby hightailed it to London—some have speculated that it was at Maly’s suggestion—to live with Kim’s disapproving mother. They were closely followed by Hans-Peter Smolka, on the run and also perhaps ordered to London by Maly. The precise truth may never be known.

Unwanted by the police and careful to hide his socialist leanings, my father stayed on in Vienna for a while, eking out a meager journalistic living. Three years elapsed before he and Smolka were reunited once more after my father followed his friend and emigrated to England after getting a much coveted visa in the winter of 1937, a heartbeat ahead of Hitler. He settled in London near Smolka and hung out his shingle as a small-time book publisher with help and sponsorship from friends.

A few weeks after Kim Philby returned to England, an Austrian “illegal” by the name of Arnold Deutsch, code-named “Otto,” approached him on a park bench. He had been sent by Maly to recruit Philby.

Hans-Peter Smolka meanwhile changed his name to H.P. Smollett Esq. to sound more English, working undercover as a London correspondent for several European papers. For a time he even ran a small news agency with Philby—all the while fruitlessly seeking entry to British intelligence on behalf of his Moscow masters. Someone should have told him British spooks mainly recruit their own.

H.P. Smollett finally made his British reputation with a series of well-written articles for the London Times describing his travels in the Russian Arctic, later turned into a best-selling book. Filled with falsehood and fabrication—it glossed over the brutality of Stalin’s gulags, for instance—Forty Thousand Against the Arctic: Russia’s Polar Empire, published in 1937, was a highly sophisticated piece of NKVD propaganda widely admired by credulous British reviewers and readers.

Smollett/Smolka’s story now took a dramatic turn as his journalistic acumen and persuasive brilliance came to the attention of a decidedly odd but powerful Englishman named Brendan Bracken, Winston Churchill’s closest adviser. Here was a key that could open a door, and Smolka walked through it.

An Irish-born arriviste adventurer raised in Australia, orange haired and ugly, Bracken was just the kind of self-made raffish figure Churchill favored. He always trusted rogues more than regulars. As proprietor of the Financial Times and The Economist and a member of Parliament, it was Bracken who buoyed Churchill’s spirits in the 1930s, repeatedly speaking and writing on his behalf. And it was Bracken who played a crucial role behind the scenes in bringing Churchill in from the cold in the nick of time as wartime leader. Bracken took a shine to Smolka and fell for his flattery.

Smolka’s many enemies said he was pushy and possessed no grace, an uncouth bull of a man with a decidedly shady air. He was both a user of others and eager to be used himself. As a child I of course saw him through my own innocent lens. He was merely my benefactor Peter and my father’s friend. Later, in my 20s, my college tutor Norman Mackenzie, himself a quondam communist who had worked in wartime intelligence and knew Smolka slightly, told me he considered my Austrian émigré godfather “a total shit” who had managed to bamboozle his way into the corridors of British power. Yet Smolka undoubtedly possessed great courage and a sort of gruesome integrity in pursuit of his murderous cause. Philby once wrote that Smolka never betrayed a fellow agent or a secret contact.

At the very moment in the summer of 1941 that Hitler broke his pact with Stalin and attacked Russia, Churchill appointed Bracken to his cabinet as minister of information in charge of making Britain’s case to the world. While Nazi Panzers punched hundreds of miles through Red Army lines, Bracken found himself looking for someone to head the Soviet Section of his ministry, newly created to boost the image of Britain’s new ally, “Uncle Joe.” He turned to Smolka. This was a plum post beyond NKVD dreams, and Smolka went at it with verve and flair.

In his words, his two priorities were to “combat anti-Soviet feelings in Britain” and also, cunningly, “to attempt to curb exuberant pro-Soviet propaganda that might seriously embarrass the government” by keeping Russian-accented and openly partisan apologists at bay and hiring sympathetic British commentators instead. He would win over the hearts and minds of England by stealing Stalin’s thunder with native British voices. Nevertheless the Soviet ambassador Ivan Maisky assured Bracken that “every effort will be made to assist Mr. Smollett to maintain close contact with the Embassy.”

His propaganda effort was on a vast scale. Ten thousand people gathered in the Royal Albert Hall to celebrate the twenty-fifth anniversary of the Red Army’s formation, including readings by Laurence Olivier and John Gielgud. Then there was a pro-Soviet film, USSR at War, seen by millions. The BBC obligingly agreed to broadcast hundreds of radio programs with Soviet content. With the help of senior BBC producer Guy Burgess, Smolka was able to shape and control the image of Russia broadcast by the most powerful medium of British mass communication.

Looking back, Oleg Gordievsy—the former KGB station chief in London and MI6 mole who made a dramatic escape to the British side in the boot of a car from Moscow to Finland in 1985—considered what he dubbed the NKVD’s “active measures coup” during the war of having Smolka direct Anglo-Soviet liaisons and information to have been its most remarkable achievement in the West. Able to satisfy both sides, my godless godfather was even awarded an OBE at war’s end by the king.

There is a vivid footnote to the Smolka story.

After returning to Vienna—where the Russians granted him preferential treatment above all others from the Russians in retrieving his family factories, which now lay in the Russian zone of control—Smolka (no longer using the name Smollett) was dragooned by his friend Brendan Bracken into helping write and produce The Third Man, the greatest of all British films and the first Cold War thriller.

The “Churchill gang” included Britain’s most prominent movie mogul, Hungarian-born Sir Alexander Korda—knighted not for his many motion pictures but for his important intelligence role in Eastern and Central Europe on Britain’s behalf in the 1930s. Korda now found he had royalties accrued before the war locked up in Austria, and the money could not be repatriated due to currency controls. It would have to be spent on the ground. At a meeting at Claridge’s Hotel in London, Bracken introduced Korda to Smolka, who had flown in for the occasion. By the time the champagne was finished, the three had hatched an outline for a movie set in Vienna to be directed on location in the city by Carol Reed. The mise en scène was to be the four-power occupation of the Austrian capital, ravaged by corruption and crime. It was a landscape Smolka knew well, and when Graham Greene was asked to write the picture, it was Smolka who was asked to show the writer around.

Peter Smolka offered Greene his best ideas and came up with most of the plot outline for The Third Man. The penicillin racket, around which the entire film hinges, was his. So too was the classic chase through the sewers at the end, based on his derring-do in spiriting comrades to safety in the civil war. As the two men sat up drinking and working out ideas at the Café Mozart or in the Sacher Hotel late into the night, they must have broached the subject of their mutual friend Kim. Greene had worked with Philby in MI6 and liked him enormously. How much the English author knew of his treason—or of Smolka’s—at that point is unclear. What is undeniable, though, is that Harry Lime—the movie’s charismatic, morally squalid central character, played memorably by Orson Welles—was partly based on the British double agent but also at least partly on the sinister Smolka.

Smolka asked for no credit on the film but got it anyway. When Major Calloway, the upright English army officer played by Trevor Howard, barks an order to his driver early in the picture to “Take us to Smolka’s!” it is perhaps a coded form of thanks—and maybe also a comic comment on Greene’s part. Smolka’s turns out to be a seedy backstreet bar.

Around the same time The Third Man was shooting in Vienna, George Orwell was busying himself with a secret “shit list” for the Foreign Office in London naming those he considered Communists or fellow travelers, both dead and alive, in Britain. It is wildly speculative, xenophobic, tinged with anti-Semitism, and unworthy of “the wintry conscience of his generation.” At the top of the typed list is Hans-Peter Smolka (a.k.a. H.P. Smollett Esq.), and in this one case Orwell got it right. Next to Smolka’s name he wrote in his spidery hand: “Surely an agent of some kind…Very slimy.” In 1944 Smolka had successfully lobbied London publishers not to publish Orwell’s Animal Farm “because it would be unhelpful to the Anglo-Soviet cause.” As a result, publication was delayed by a year, enraging Orwell and giving him additional reason to suspect Smolka. But if Orwell rumbled him, others probably did, too. For their own reasons, they turned a blind eye. In elite British wartime circles, Marxist tendencies were mostly discounted as cause for suspicion. British spymaster Sir Dick White—the only man ever to head both MI5 and MI6—has said of Britain at war that “as far as we were concerned anyone who was against the Germans was on the right side.” Working high up in counterintelligence, he knew Smolka and, while aware of the burly Austrian’s pro-Soviet sympathies, raised no objection to his continued employment. In a series of encounters with White, Smolka apparently managed to persuade him—and through him ultimately Churchill, at least for a while—that Stalin had no intention of dominating Europe when the war ended, a cleverly planted piece of disinformation that proved hugely helpful to the Kremlin at the time.

I last saw my godfather on a visit to Vienna with my dad in the summer of 1967. The scene that sticks in my mind is the sunlit garden of his magnificent suburban villa. Smolka had become fabulously rich from Tyrolia, the ski equipment manufacturer he owned. By then he was also completely paralyzed, confined to a wheelchair by his advanced sclerosis. Around him were two aged former revolutionaries paying court. On one side was Ernst Fischer, once the Austrian Communist Party’s leading public intellectual, who sat out the war in Moscow working for the Comintern. On the other was Teddy Prager, the party strategist who was in London during the Blitz drilling Marxist dogma into young minds at the LSE. Like Smolka, both had escaped Vienna and certain execution in 1934. There was much laughter, flagons of Grüner Veltliner, and many stories. The tone, however, was rueful. Here were three aging radical intellectuals who had once risked their young lives for a revolutionary god. Forty years on, around a simple wooden table under Smolka’s apple tree as the dappled light began to fail, the erstwhile comrades in arms who had staked their all on a sure vision of heaven on earth found themselves like former believers in the true cross who have lost their faith—accepting the truth that their god had died.