Street Life, Harlem, by William H. Johnson, c. 1939. Smithsonian American Art Museum, gift of the Harmon Foundation.

As people continue to gather across the world to protest police brutality and anti-Black racism, Roundtable will feature voices from the past who rose up against injustice and told stories or witnessed moments that rhyme with the ones unfolding before us.

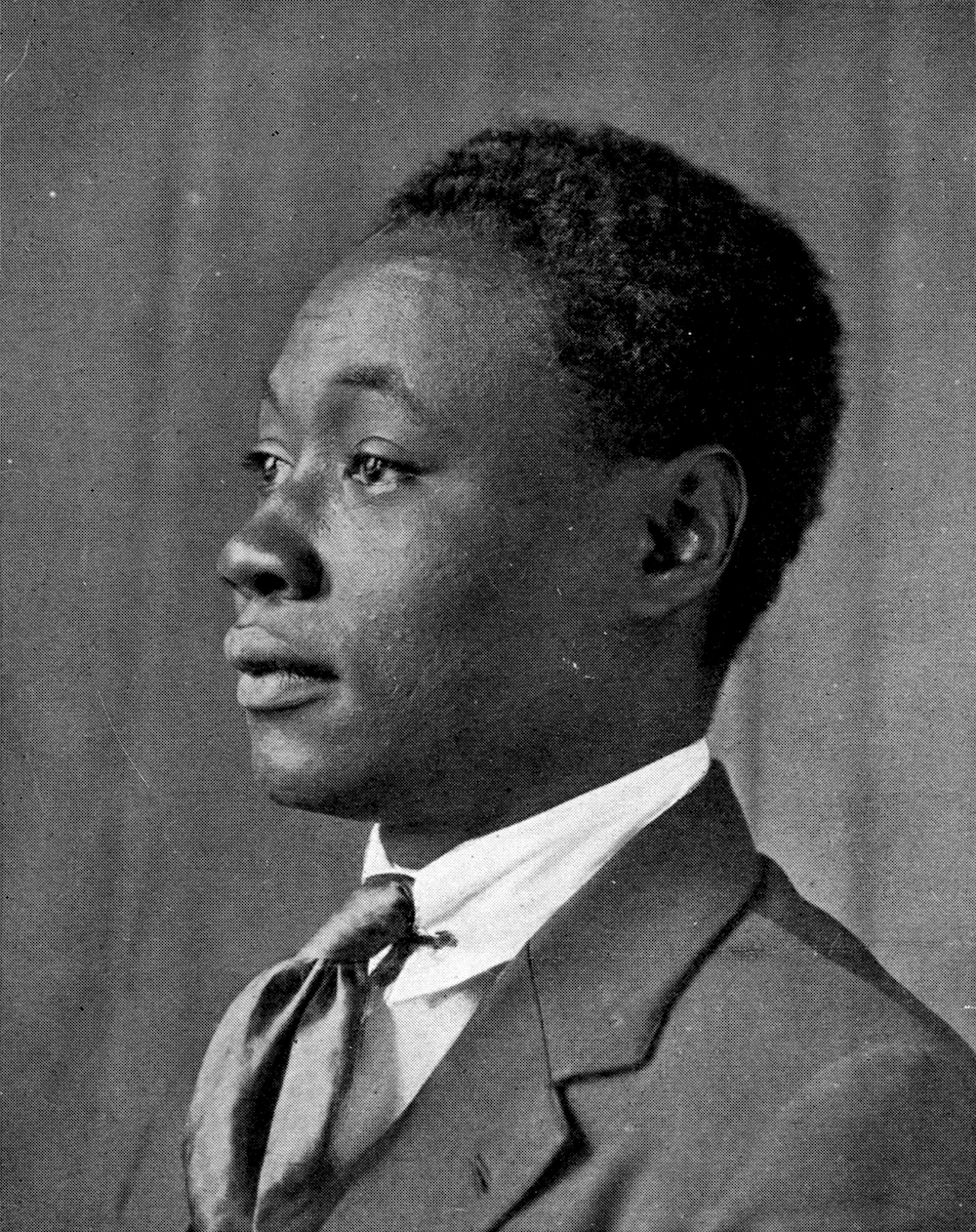

In 1919 Claude McKay was not yet the prominent Harlem Renaissance poet and novelist he would become only a few years later. He was working as waiter in a railway dining car and writing poetry about the things he saw. It was during the Red Summer of 1919—a period marked by intense racialized violence against Black Americans—that he wrote one of his most famous poems, “If We Must Die.” The Harlem Renaissance novelist Wallace Thurman later wrote that McKay was the only Black poet who wrote “revolutionary or protest poetry.” Although Thurman thought McKay a lesser poet who “could never shape the flames from the fire that blazed within him,” he praised the fact that “If We Must Die” was not a lament and did not seek mercy; McKay would never apologize for his Blackness.

“If We Must Die” first appeared in a selection of McKay’s sonnets and songs published in the July 1919 issue of The Liberator, a socialist magazine founded by Max and Crystal Eastman. Max Eastman introduced McKay as a “poet practically unknown to the public” with “a bold and unhesitating mind,” noting that his poems “show a fine clear flame of life burning and not to be forgotten.”

The Negro Dancers

I

Lit with cheap colored lights a basement den,

With rows of chairs and tables on each side,

And, all about, young, dark-skinned women and men

Drinking and smoking, merry, vacant-eyed.

A Negro band, that scarcely seems awake,

Drones out half-heartedly a lazy tune,

While quick and willing boys their orders take

And hurry to and from the near saloon.

Then suddenly a happy, lilting note

Is struck, the walk and hop and trot begin,

Under the smoke upon foul air afloat;

Around the room the laughing puppets spin

To sound of fiddle, drum and clarinet,

Dancing, their world of shadows to forget.

II

’Tis best to sit and gaze; my heart then dances

To the lithe bodies gliding slowly by,

The amorous and inimitable glances

That subtly pass from roguish eye to eye,

The laughter gay like sounding silver ringing,

That fills the whole wide room from floor to ceiling,—

A rush of rapture to my tried soul bringing—

The deathless spirit of a race revealing.

Not one false step, no note that rings not true!

Unconscious even of the higher worth

Of their great art, they serpent-wise glide through

The syncopated waltz. Dead to the earth

And her unkindly ways of toil and strife,

For them the dance is the true joy of life.

III

And yet they are the outcasts of the earth,

A race oppressed and scorned by ruling man;

How can they thus consent to joy and mirth

Who live beneath a world-eternal ban?

No faith is theirs, no shining ray of hope,

Except the martyr’s faith, the hope that death

Some day will free them from their narrow scope

And once more merge them with the infinite breath.

But, oh! they dance with poetry in their eyes

Whose dreamy loveliness no sorrow dims,

And parted lips and eager, gleeful cries,

And perfect rhythm in their nimble limbs.

The gifts divine are theirs, music and laughter;

All other things, however great, come after.

The Barrier

I must not gaze at them although

Your eyes are dawning day;

I must not watch you as you go

Your sun-illumined way;

I hear but I must never heed

The fascinating note,

Which, fluting like a river-reed,

Comes from your trembling throat;

I must not see upon your face

Love’s softly glowing spark;

For there’s the barrier of race,

You’re fair and I am dark.

After the Winter

Some day, when trees have shed their leaves,

And against the morning’s white

The shivering birds beneath the eaves

Have sheltered for the night,

We’ll turn our faces southward, love,

Toward the summer isle

Where bamboos spire to shafted grove

And wide-mouthed orchids smile.

And we will seek the quiet hill

Where towers the cotton tree,

And leaps the laughing crystal rill,

And works the droning bee.

And we will build a lonely nest

Beside an open glade,

With black-ribbed blue-bells blowing near,

And ferns that never fade.

A Capitalist at Dinner

An ugly figure, heavy, overfed,

Settles uneasily into a chair;

Nervously he mops his pimply pink bald head,

Frowns at the fawning waiter standing near.

The entire service tries its best to please

This overpampered piece of broken-health,

Who sits there thoughtless, querulous, obese,

Wrapped in his sordid visions of vast wealth.

Great God! if creatures like this money-fool,

Who hold the service of mankind so cheap,

Over the people must forever rule,

Driving them at their will like helpless sheep—

Then let proud mothers cease from giving birth;

Let human beings perish from the earth.

The Little Peoples

The little peoples of the troubled earth,

The little nations that are weak and white;—

For them the glory of another birth,

For them the lifting of the veil of night.

The big men of the world in concert met,

Have sent forth in their power a new decree:

Upon the old harsh wrongs the sun must set,

Henceforth the little peoples must be free!

But we, the blacks, less than the trampled dust,

Who walk the new ways with the old dim eyes,—

We to the ancient gods of greed and lust

Must still be offered up as sacrifice:

Oh, we who deign to live but will not dare,

The white world’s burden must forever bear!

A Roman Holiday

’Tis but a modern Roman holiday;

Each state invokes its soul of basest passion,

Each vies with each to find the ugliest way

To torture Negroes in the fiercest fashion.

Black Southern men, like hogs await your doom!

White wretches hunt and haul you from your huts,

They squeeze the babies out your women’s womb,

They cut your members off, rip out your guts!

It is a Roman holiday, and worse:

It is the mad beast risen from his lair,

The dead accusing years’ eternal curse,

Reeking of vengeance, in fulfillment here

Bravo Democracy! Hail greatest Power

That saved sick Europe in her darkest hour!

If We Must Die

If we must die, let it not be like hogs

Hunted and penned in an inglorious spot,

While round us bark the mad and hungry dogs,

Making their mock at our accursèd lot.

If we must die, O let us nobly die,

So that our precious blood may not be shed

In vain; then even the monsters we defy

Shall be constrained to honor us though dead!

Oh, kinsmen! we must meet the common foe!

Though far outnumbered, let us show us brave,

And for their thousand blows deal one death-blow!

What though before us lies the open grave?

Like men we’ll face the murderous, cowardly pack,

Pressed to the wall, dying, but fighting back!

Read the other entries in this series: Anna Julia Cooper, James Weldon Johnson, Walter F. White, and a Haitian hymn.