The Experts, by Alexandre-Gabriel Decamps, 1837. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, H.O. Havemeyer Collection, bequest of Mrs. H.O. Havemeyer, 1929.

One of the distinctive features of modern life is the rating. Brunch spots, autofiction, electric cars, dramedies, fishing tackle, photography retrospectives—everything has a rating, and we rate everything. This quantification of taste, or at least of satisfaction, has its beginnings not in the internet age but rather in a much earlier and rather unlikely place: a half-joking appendix to a book by a Frenchman called Roger de Piles.

De Piles was the most influential French art critic and theorist of the second half of the seventeenth century. He was also a spy, like many scholars who came after him (perhaps most notoriously Anthony Blunt, an expert on the painter Nicolas Poussin and one of the Cambridge Five). Under the pretense of seeking out new acquisitions for Louis XIV, de Piles worked as a secret negotiator in the German-speaking lands and Holland. He even spent five years incarcerated in the Hague during the War of the League of Augsburg after being caught with a false passport in 1692, and his Abrégé de la vie des peintres (The Art of Painting, and the Lives of the Painters), a collection of microbiographies in the style of Vasari, counts as one of the few works of art history written in a prison cell. In recognition of his service in matters connoisseurial and clandestine, Louis granted him an annual pension of two thousand livres upon his release. A few years later, with help from friends like Michel Amelot de Gournay, the nobleman he tutored for much of the 1660s and whom he served as secretary during de Gournay’s diplomatic career in the 1680s, de Piles was elected to France’s Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture in 1699 as conseiller honoraire, something like its theorist-in-chief.

Since its foundation in 1648, the Royal Academy had been the center of what could be called higher artistic education in France. To become painters, pupils apprenticed to master craftsmen, working within the old guild structure. But to become artists, they had to go to the Academy, where they studied geometry, perspective, anatomy, and above all what makes good art. At the Academy, de Piles explained that he aimed to teach “young pupils, who may have set out in a right path, and for all those who, after acquiring some tincture of design and coloring, have impartially examined the best works, and are docile enough to embrace those truths which may be hinted to in them.” In 1708 he collected his Academy lectures in Cours de peinture par principes (Principles of Painting), a book that summed up the theory and practice of painting in seventeenth-century France, and also paved the way for its future.

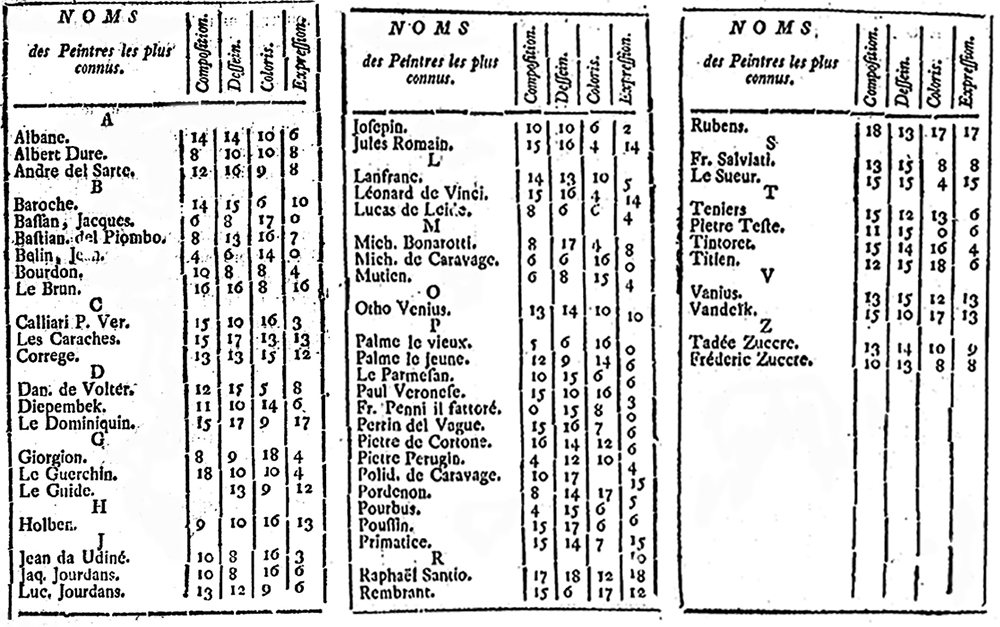

Attached to the Cours is the slim appendix that made the book famous—or infamous, depending on your point of view. In a little table called the Balance des Peintres, de Piles rated artists on their composition, design, color, and expression with scores from zero to twenty. The rigorously neoclassical Poussin, for example, received a seventeen for design but only a six for color; the more sensual, colorful Peter Paul Rubens, by contrast, merited a thirteen and a seventeen in the same categories. Despite being little more than an intellectual plaything, the Balance immediately took off, widely imitated in the Enlightenment and thoroughly ridiculed in the Romantic period that followed. Whether jesting or no—and whether for better or for worse—de Piles’ effort to “geometrize taste,” as one eighteenth-century admirer put it, takes on a new importance in our age of aggregation, where quantification and criticism blend together. The Balance stands out not just as an Enlightenment-era curiosity but as the unwitting origin of a critical wave now reaching its crest in the twenty-first century.

De Piles’ critical opinions were no mystery. In his books, particularly the Abregé, he wrote at length on the great artists of the Western tradition. His colleagues at the Academy held that design was the most important aspect of painting: a good painter effectively imitates reality through the composition of a painting. De Piles, by contrast, advocated for color as more important than design—for the brushy fleshliness of Rubens’ nudes over Poussin’s perfectly balanced crystalline compositions. Drawing precepts not so much from poetry or musical composition but from the realities of the medium itself, de Piles derived a native theory of painting, at the center of which was the canvas and the subjective experience of the person viewing it. He considered artists not so much moral teachers as craftsmen whose ultimate duty is to make a compelling piece of visual art that “seduces our eyes.”

In his preface to the Balance, de Piles hinted that a few of his readers wanted a more concrete guide not to the art of painting but to the actual artists whose works you might encounter in a gallery or an auction house.

Some persons, curious to know the degree of merit of every painter of established reputation, have desired me to make a kind of balance, where I might set down, on one side, the painter’s name, and the most essential parts of his art, in the degree he possessed them; and, on the other side, their proper weight of merit; so as, by collecting all the parts, as they appear in each painter’s works, one might be able to judge how much the whole weighs.

It’s not hard to imagine how a student, anxious to get ahead within the world of academic art—and anxious to make a living—might prefer solid, utilitarian rankings to the more expansive judgments of criticism in prose. But more likely de Piles was referring to the people he spent a lifetime collaborating with: aristocratic collectors, who needed help cultivating their taste and, more prosaically, making acquisitions. The balance was first and foremost a commercial tool, and brings to the obscurity of aesthetic disputes the practical clarity of the marketplace. De Piles’ quantification helps teach discerning young gentleman how to look—and how to buy. “It is only through comparison,” he wrote in 1677, “that things may be deemed good or bad.”1

De Piles rated fifty-six painters (none then alive) on a scale from zero to twenty in the four categories he believed to be most salient: composition, design, color, and the mysterious “expression”—what he glossed as la pensée du coeur humain, literally “the thought of the human heart,” or, as a 1743 translation puts it, “the general thought of the understanding.” In reality, twenty is granted only to “sovereign perfection; which no man has fully arrived at,” and nineteen goes to the “highest degree that we know, but which no one has yet gained.” Eighteen is effectively the highest rating possible, yet Rubens, de Piles’ favorite painter, reaches such heights only once, in composition. At the other end of the spectrum, the critic doled out a fair number of zeros to artists now safely canonized: in expression, for example, to Giovanni Bellini, Jacopo Bassano, Caravaggio, Jacopo Palma, and Giovanni Francesco Penni (also given a zero for composition). De Piles doesn’t add the numbers together, dodging the question of whether some criteria should be weighted more than others, but addition does seem to give a general portrait of de Piles’ point of view: Raphael and Rubens are tied for first, with sixty-five points; the portraitist Anthony van Dyck comes in sixth with fifty-five; Poussin comes in eighth with fifty-three; Titian rounds out the top ten with fifty-one.

Like any effort to translate the analog into the digital, the Balance encodes a certain structure of values, a way of seeing. De Piles’ quietly grinds his ax by weighting color equally with design, since for the average neoclassical French art critic, composition—the balanced unity of a canvas, a product of the artist’s mind, rather than his hand—was more important than the application of paint. More interestingly, by including a score for “expression” de Piles makes room for a level of subjectivity in style, and in his own critical judgment, that moves far beyond the Academy’s traditional elevation of a painting’s moral worth, educational value, and technical perfection. Elsewhere in the Cours, he makes clear that expression doesn’t mean feeling, but rather signifies “the representation of an object, according to its character and nature, and according to the turn which the painter has a mind to give it for the benefit of his work.” It’s that je ne sais quoi, that subtle justness of representation that makes a painting feel adequate to its subject and the painter’s intent. This seemingly arch-rational table conceals the subjectivity that would come to define a more modern style of criticism, one that abandoned the neoclassical vision of painting as discursive and didactic and instead focused on aesthetic interest and affective response.

It’s precisely this subjectivity that makes Piles’ judgments debatable, if not downright ridiculous. Who could look at Titian’s portrait of his friend Pietro Aretino, or of Ludovico Beccadelli, for example, and agree that his expression deserves only a six? Why does Paolo Veronese’s portrait of Giuseppe da Porto and his son Adriano earn a mere three?

On the surface, the Balance reflects the early Enlightenment’s increasing faith in reason and quantification—the outlook that the secretary of the Paris Academy of Sciences Bernard Le Bovier, sieur de Fontenelle, summed up when he wrote in 1699 that “a work on ethics, politics, criticism, and, perhaps, even rhetoric will be better, other things being equal, if done by a geometer.” Yet de Piles doesn’t come up with his judgments via any kind of system, and makes no claim to objectivity. “Opinions are too various in this point to let us think that we alone are in the right,” he wrote. “All I ask is the liberty of declaring my thoughts in this matter, as I allow others to preserve any idea they may have different from mine.” De Piles borrows the seemingly impersonal language of mathematics to make an almost startling disclosure and summary of one individual’s judgment: what looks like objectivity is actually a kind of radical transparency.

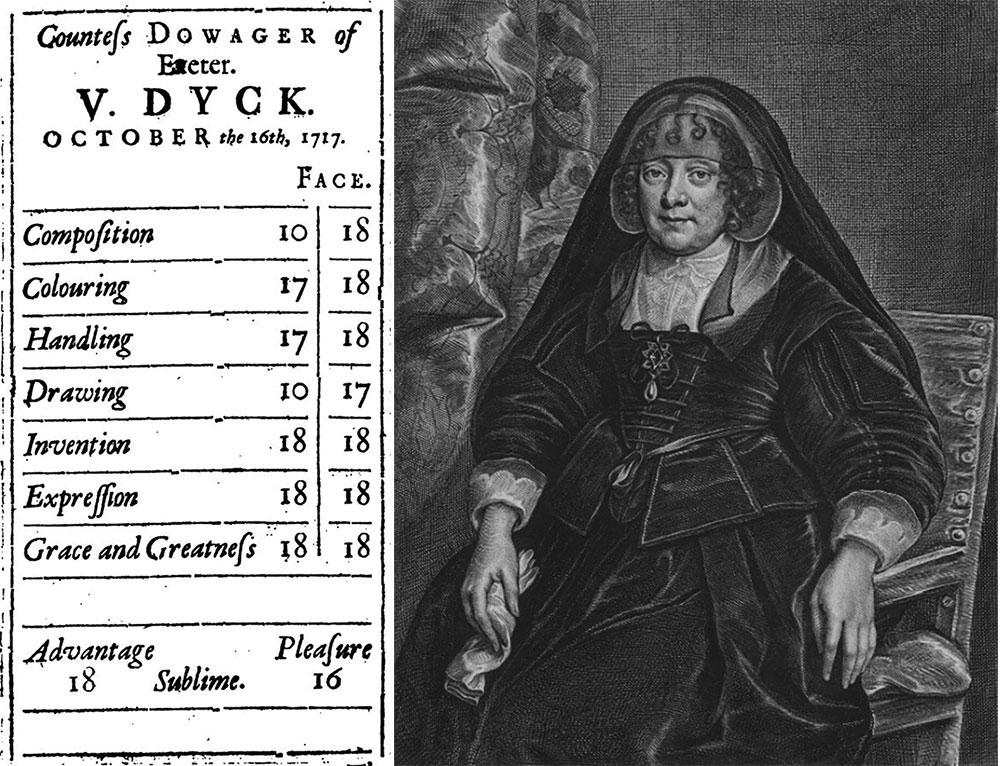

De Piles wrote that his table was merely an attempt “to please myself than to bring others into my sentiments.” Regardless of how seriously it was intended, the Balance immediately drew attention and imitators. The most inspired of de Piles’ followers was the British painter Jonathan Richardson—remembered now as the author who spurred Joshua Reynolds to become an artist—who was likely responsible for the 1743 translation of the Cours into English. He critiqued and expanded de Piles’ Balance in his 1719 Essay on the Whole Art of Criticism as It Relates to Painting. Richardson tried to make his ratings more informative by adding the categories of “handling,” “invention,” and “grace and greatness”; when discussing a portrait by van Dyck, he also gave individual scores for the face alone. (Richardson was particularly proud of his own portraits.)

Unlike de Piles, who merely offered the Balance to his readers, Richardson wanted us to join in. He printed a blank line for the reader to create their own category and left room at the bottom of the table for the scribbling of observations. “A little pocketbook might be always ready, every leaf of which should be prepared” this way, Richardson suggested, “and when one considers a picture an estimate might be made of it by putting such figures under each head as shall be judged proper; or more than one if in one part of the picture there by any considerable difference from what is in another.” This exercise in quantitative criticism was meant to help organize viewing and stimulate reflection, and to form the foundation of a personal database of aesthetic encounters:

Whoever practices a regular way of considering a picture or drawing will, I am confident, find the benefit of it; and if they will moreover note down the degrees of estimation in this manner ’twill be of further use; ’twill give a man a more clear and distinct idea of the thing, ’twill be a further exercise of his judgment, a remembrance of what he has seen, and by considering it together with the picture months, or years, afterwards he will see whether his judgment is altered, and wherein.

Similar efforts to quantify taste were later attempted in other domains, with critics modifying the Balance for use with other kinds of art. The Scottish poet-physician Mark Akenside published his Ballance of Poets in 1746 (Homer and Shakespeare come on top, though the latter gets a zero for “critical ordonnance,” or internal structure), and in 1758 an anonymous “Scale of the Tragedians and Comedians” in London’s Theatrical Review rated David Garrick the best actor in town. The balance form also took off in Germany: in 1757 the poet Christoph Martin Wieland published his Balance der großen Poeten (in which, notably, no German poets were included), and in 1767 the poet and composer Christian Friedrich Daniel Schubart came out with his Kritische Skala der vorzüglichsten deutschen Dichter (Critical Scale of the Foremost German Poets), in which the “national genius” Friedrich Gottlieb Klopstock ranked ahead of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and Friedrich Schiller. In 1784 the almost comically devout French naturalist Marie Le Masson Le Golft even published a Balance of Nature, in which she ranked animals, plants, and even minerals on color, design, and “instinct” in order to better understand the hierarchy of God’s creation, convinced, as she wrote, that “one cannot contemplate nature without rising up to its author.”

But as Romanticism took root, and with it a new understanding of art and artists, the Balance began to seem not just quaint but distasteful. In 1810 the critic Jean-François Sobry spoke for many when he dismissed de Piles’ experiment: “Let us love what is beautiful when we see it, without bothering about weighing it. Let us repay the enthusiasm of talent with the enthusiasm of esteem; and leave the scales to the merchants.” Eugène Delacroix, writing in 1854, pointed out that de Piles and his followers seemed to regard the artist and his production as a kind of composite of discrete qualities, as if, “with goodwill and a bit of effort, each of these remarkable men could have rebalanced these qualities…and could have arrived (in his opinion) much closer to true beauty.” In Delacroix’s view a painting isn’t the product of some “delightful chemistry” of the sort de Piles used to analyze great artists but rather represented an integral unity, an indivisible whole as complex as its creator.

Though the Romantic insistence on the subjectivity of the artist and the integrity of the artwork was indeed in conflict with de Piles, Delacroix and his contemporaries would certainly have agreed with their predecessor’s placement of the subjectivity of the viewer at the center of the critical consideration of painting. Though he did indeed discuss the composition of the “whole together” of the painting—its overall layout and conception—as a kind of “machine, whose wheels give each other mutual assistance, as a body, whose members have a mutual dependence,” de Piles wanted the painter to engineer an aesthetic mechanism that “stops and entertains the spectator, and invites him to please himself with contemplating the particular beauties of the picture.” The metaphor of the machine and the conceit of the balance stem from the spirit of the age. But the radical turn toward subjectivity, even relativism, was the true innovation.

Even though he put individual experience at the center of his aesthetics, de Piles was still confident in the possibility, and the worth, of critical judgment. Yet the very forces he helped unleash have called the whole critical enterprise into question. It’s not a coincidence that so much modern art has put the difficulty and even the futility of judgment front and center; from Marcel Duchamp’s urinal and Andy Warhol’s soup cans to the gleeful absurdities of NFTs, the role of the piece is to make you ask and argue about whether it even counts as art, and, one suspects, to make the whole conversation seem ridiculous.

In his cheeky 2014 work also called the Balance of Painters, the Norwegian artist Dag Erik Elgin painted de Piles’ scores on forty-nine little canvases, the big serif font stacked vertically on pleasantly innocuous pastel backgrounds. Though each painting shows an individual painter’s score, Elgin doesn’t label any of them, and we have to return to the Balance itself to figure out which is which. The artist transforms the Balance into a little gallery of de Piles’ judgments, a museum in which criticism has supplanted its object, and the conversation has become the content. And whatever de Piles’ intention, that’s one way of making sense of the Balance: as itself a kind of art piece, a big intellectual and aesthetic gag—one that anxiously points to the proximity of price and appreciation, of selling and seeing, and whose very absurdity makes us reconsider how and why we talk about art.

1 As Andrew McClellan observed in Inventing the Louvre, de Piles’ belief in the value of comparison was something of a commonplace of early modern epistemology. John Locke, for example, described the importance of comparison for learning in his Essay Concerning Human Understanding, as did Louis de Jaucourt in his article on comparison in the Encyclopédie. Leon Battista Alberti also argued for the centrality of the comparative method in the formation of a painter: “All things are known by comparison,” he wrote in 1435 in Della Pittura (On Painting). ↩