The rebuilt Blennerhassett mansion. Courtesy of the West Virginia Division of Commerce.

Audio brought to you by Curio, a Lapham’s Quarterly partner

Harman and Margaret Blennerhassett moved to the United States to lay low. Although some have suggested they left England to avoid scandal—Margaret was both Harman’s wife and his niece—their flight had more to do with Harman’s political allegiances. Just a short time after receiving his inheritance from his wealthy aristocratic parents, Harman became a financial backer and secretary for the Society of United Irishmen, a group seeking to free Ireland from British rule. When British authorities began locking up its leaders and trying them for sedition, Harman sold the family estate and, in the spring of 1796, sailed from Europe with hopes of starting over.

The Blennerhassetts had the means to make nearly any kind of life they wanted. Harman sold his estate for £28,000, about $4.5 million today. But the couple wanted a secluded home, away from the East Coast’s major cities. They found one: a 169-acre plot on an island in the Ohio River, just south of modern-day Parkersburg, West Virginia. It would have made a perfect hideaway if not for the Blennerhassetts’ conspicuous tastes.

At a time when most nearby structures would have been built from logs, the couple set about constructing a mansion with a two-and-a-half-story main house and curving Palladian breezeways, all painted in brilliant white. They seated the home on the island’s highest point and had workers cut down trees along the water’s edge to create an unobstructed view. Passing boats couldn’t help but notice their miniature Mount Vernon.

Socialites from nearby Marietta, Ohio, and as far away as Pittsburgh flocked to what came to be known as Blennerhassett Island for dances, dinners, concerts, and readings. Everyone in the valley soon knew about Harman, the accomplished musician, amateur physician and scientist, lawyer, bibliophile, and businessman. He became known for his loyalty, kindness, and near-blindness. He was so myopic that he read with his hooked nose nearly touching the page and, when he went bird hunting, required assistance aiming his gun.

Margaret drew even more attention. She was tall and thin with fair skin, blue eyes, and a quick mind. She recited Shakespeare, read some French, was a talented cook and seamstress, and enjoyed dancing and card games. She wore high-waisted empire dresses around the house but, when riding her favorite horse, Robin, donned a scarlet habit with gold buttons, gloves, leather boots, and a white beaver fur hat with ostrich feathers.

The couple’s outsize personalities won them a prominent place among the frontier bourgeoisie in Marietta, Ohio, and nearby Wood County, Virginia. But that notoriety also brought trouble to their door.

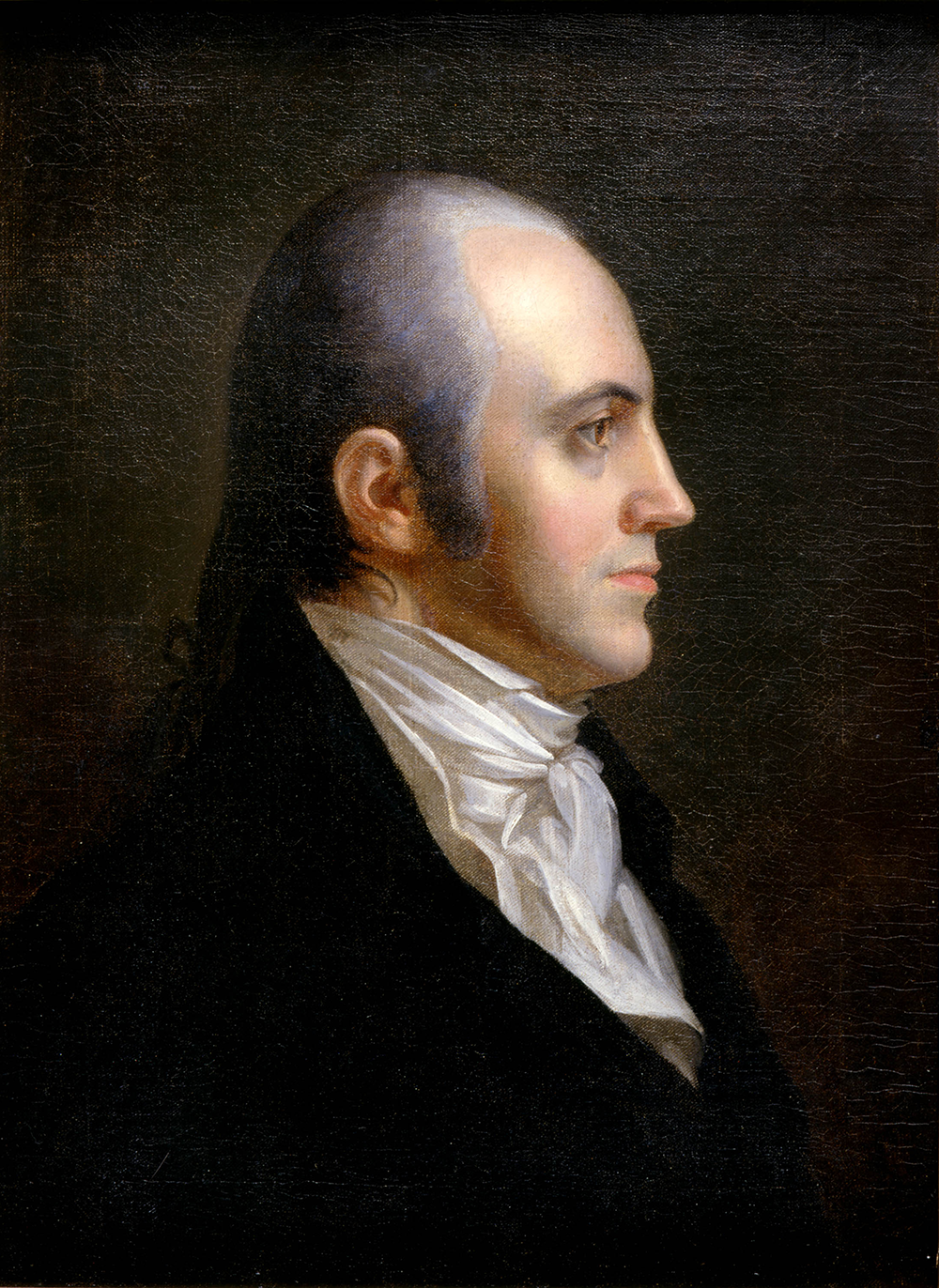

One day in the spring of 1805, Aaron Burr’s boat docked at Blennerhassett Island. Burr was searching for a second act after his duel with Alexander Hamilton ruined his political career. Historians still argue whether his next plans were to invade Mexico, try to rally the western states together to secede, or just settle the 40,000-acre lease he’d been granted in the Texas Territory. Burr tended to tailor his pitch according to his audience.

No matter his course of action, Burr would need a base of operations somewhere on the Ohio River, a strategic midpoint between the big cities of New England and the western territories. He also needed money. And he figured Harman Blennerhassett could help with both.

We don’t know which scenario Burr laid out on Blennerhassett Island, but he promised Harman would profit from participating. The proposition could not have come at a better time. Behind Blennerhassett Island’s opulent appearances, things were falling apart.

Harman was a generous man but lacked common sense when it came to money. He overpaid for everything from his acreage on the island to the mussel shells used to make plaster for the mansion. He loaned money to people who never paid it back and was frequently duped into bad business deals. He planted a hemp crop only to watch the market fail. He invested in Dudley Woodbridge Jr. & Co.—which ran general merchandise stores across southeastern Ohio—only to see the firm’s finances take a hit during an economic downturn. The Blennerhassetts were quickly burning through their savings and, knowing the situation was untenable, started talking about selling their home and moving south to get into the cotton business. Burr and his plot must have seemed like a godsend.

Although not expecting such a high-profile guest, the Blennerhassetts entertained Burr until well after dark. He refused the couple’s offer of a bed, insisting on sleeping in his houseboat, so the Blennerhassetts walked him back to the water by candlelight. When they reached the bank, Burr slipped and fell. “That’s an ill omen,” the former vice president said to no one in particular.

He left after breakfast the following morning. Soon Burr and Harman were exchanging letters. “I should be honored in being associated with you, in any contemplated enterprise you would permit me to participate in,” Harman wrote to Burr. “I am disposed, in the confidential spirit of this letter, to offer you and my friends’ and my own services in any contemplated measures in which you may embark.”

Although he told Burr he couldn’t provide money, Harman volunteered his credit—which was helpful since Burr was already racking up his own debts. Harman contracted a local boatbuilder to build fifteen river boats for the expedition. He also began stockpiling provisions, including flour, cornmeal, whiskey, and a hundred barrels of salted pork.

The Blennerhassetts also tried to raise manpower for Burr’s mission. Margaret stopped the entertainment at one of their balls to deliver a short speech encouraging young men in attendance to sign up. In his own conversations with potential recruits, Harman promised $12 a month plus provisions and 150 acres of land. He also started penning columns for Marietta’s Ohio Gazette calling for the secession of western states and a takeover of Mexico, seemingly in line with at least some of Burr’s plans. Although published under the pen name Querist, Harman claimed authorship to anyone who would listen.

By early December 1806, Blennerhassett Island was dusted with snow and consumed in a flurry of activity. Harman and fellow Burr recruit Comfort Tyler were getting ready to head down the Ohio. They had to move fast. Rumors were rampant about Burr’s designs. President Thomas Jefferson suspected the expedition had treasonous intentions and issued a proclamation calling for the arrest of the former vice president and his conspirators.

Governor Edward Tiffin had already mobilized the Ohio militia, which descended on Joseph Barker’s boatyard, located about twenty miles upriver from Blennerhassett Island. The militiamen seized the fifteen boats Harman had hired Barker to build, but it was too late. Tyler had already slipped down from Pittsburgh with four boats that were now moored at the island. Working by the light of a bonfire, the family’s servants and slaves hurried to load the boats with provisions. Harman and company shoved off around 1 a.m. on December 11, leaving Margaret and the children behind.

Burr managed to keep his recruits in the dark about his true intentions, promising to divulge the full details when the time was right. But his plot—whether that entailed secession of the recently acquired western states, an illegal invasion of Spanish-controlled Mexico, or the settlement of his lease in Texas—was now under way. Harman and Tyler would meet up with more of Burr’s men along their journey down the Ohio. Burr was in Tennessee at the time, getting boats from Andrew Jackson in Nashville and trying to raise additional recruits. He would meet the rest of the party at the mouth of the Cumberland River and then proceed down the Mississippi River.

Just hours after Harman and company shoved off, an unofficial militia from Wood County, Virginia—formed in response to Jefferson’s proclamation—overtook the island. When they realized the boats had already gone, the militiamen broke down fences for firewood, raided the mansion’s food supply and wine cellar, locked servants in the well house, and set up camp on the ground floor of the main house. A drunken soldier discharged his rifle in the entrance hall. The bullet tore through the ceiling and into the upper floor, terrifying Margaret and her two young sons.

Margaret managed to leave the island two days later when another band of Burr volunteers from Pittsburgh, headed south to join the rest of the expedition, arrived at the island. Although initially detained as part of Burr’s plot by the ragtag Wood County militia, the volunteers were acquitted by a hastily assembled court and allowed to leave with Margaret, her sons, the family’s silver, and some books, furniture, musical instruments, and papers. She would never see their island home again.

They reunited with Harman a few days later. The remainder of the trip was largely uneventful, if miserable. The party suffered harsh weather and leaking boat roofs. It was nearly impossible to keep the flotilla together, and boats frequently got stuck in powerful eddies.

Burr joined shortly after Christmas with his boats and some hired men, having failed to find any recruits in Tennessee. He did try to recruit more volunteers along the way, without success. Harman had once predicted Burr’s army would include a thousand men. By the time they reached Mississippi, the company boasted only about one hundred people.

The plan—whatever it may have entailed in the end—quickly crumbled. Burr learned of Jefferson’s order and the $5,000 bounty placed on his head by Louisiana governor James Wilkinson. He surrendered to Cowles Mead, governor of Mississippi, but then escaped into the wilderness for a time before being apprehended a few months later. Harman was arrested in Mississippi, released, and then rearrested in July 1807 in Lexington, Kentucky. He had been headed back to the island to salvage what remained of his property but instead was taken to Richmond, Virginia, to stand trial for treason.

While other prisoners at the Virginia State Penitentiary were packed into dank, overcrowded cells and forced to work in the attached nail and shoe factories, Harman lived in relative luxury. He stayed in an apartment-sized cell, did not have to work like the other prisoners, entertained many visitors, and received meals from a nearby tavern; Burr’s daughter, Theodosia, also sent him oranges, lemons, tea, and cakes. Nevertheless, he found the situation demeaning and demoralizing. The prison stunk, so much so that he had to stand on a chair to breathe fresh air from the cell window. A noted hypochondriac, he wrote in his journal of headaches, fever, cough, diarrhea, flu, and “a sort of ringworm” on his face. These ailments, real or imagined, were exacerbated by Harman’s daily walk to the courthouse, a mile and a half through the sweltering Virginia summer.

Court proceedings proved even more humiliating. Although Harman was not on trial himself—the government first had to demonstrate Burr had committed treason—an examination of his character and activities was an important part of the prosecution’s arguments. The preparations on Blennerhassett Island were the closest thing prosecutors could find to an act of treason, so they needed to argue that those activities were of a military nature. And since the aloof, nearly blind Harman seemed unlikely to instigate violent revolution, the government needed to show he was merely Burr’s pawn.

The centerpiece of the government’s case against Burr was a four-hour speech by U.S. Attorney General William Wirt examining how Harman came under Burr’s spell. “The conquest was not difficult. Innocence is ever simple and credulous,” Wirt crowed. “Such was the state of Eden when the serpent entered its bowers!” He told the court the naive, easily duped Harman was no revolutionary—forgetting or perhaps unaware of Harman’s association with the Society of United Irishmen—which meant it must be Burr who was the real traitor.

While prosecutors sought to portray Harman as naive, the defense sought to portray him as incompetent. “You know Mr. Blennerhassett well,” said Burr—who served as part of his own legal team—as he cross-examined Harman’s business partner Dudley Woodbridge Jr. “Was it not ridiculous to be engaged in a military enterprise? How far can he distinguish a man from a horse? Ten steps?”

Woodbridge had to agree: “He cannot know you from any of us at a distance we are now from one another. He knows nothing of military affairs.” Under questioning from Wirt, Woodbridge admitted “it was mentioned among people in the country that [Harman] had every kind of sense but common sense.”

After eight days of arguments, Chief Justice John Marshall decided the prosecution had failed to prove an “overt act of war.” This was perhaps the lone success of Burr’s expedition—he kept his true intentions so opaque that the charges could not stick. Marshall declared no more witnesses would be called and sent the jury into deliberation. Jurors returned the next day with a decision: not guilty.

Harman’s troubles were far from over. The government continued to try to bring treason charges against Burr and his conspirators, although those efforts were not successful. Meanwhile Harman had creditors nipping at his heels. Burr’s son-in-law Joseph Alston reimbursed him a few thousand dollars, but Harman remained on the hook for most of the $37,500 (about $760,000 today) in debt he’d racked up on the failed expedition. He was forced to sell his island home, much of the family’s possessions, and his share in Dudley Woodbridge Jr. & Co. He had enough left over to purchase a thousand-acre cotton plantation in Mississippi, which the Blennerhassetts dubbed La Cache, the Hiding Place. But they would soon sell that, too, as mounting debt, failing crops, and dropping cotton prices left their fortunes even further diminished.

The family moved to Montreal, where a school friend had promised Harman a seat on the bench. But when the friend succumbed to a rabid fox bite, Harman’s job prospects died with him. By 1824, Harman, Margaret, and their youngest son Joseph had moved back to Great Britain. (Dominic and Harman Jr. were now grown and opted to stay in North America.) The family lived with Harman’s sister in Bath before moving to Jersey, and then settled on the Isle of Guernsey, where the climate was warmer and living expenses lower.

Harman died of a stroke in 1831. He was sixty-six years old. Margaret died eleven years later while visiting Harman Jr. in New York City. Destitute and grasping at straws to restore at least a portion of her former fortunes, she had returned to the United States in the hope that Congress would reimburse her for the fifteen boats the government had seized during the Burr plot. She died before any action could be taken on her claim.

Their island Eden had been destroyed years before. Local farmer George Neale rented the mansion after the Blennerhassetts left. In March 1811, his family awoke to find the house engulfed in flames, escaping with little more than the clothes on their backs.

Neale’s son George Neale Jr. later purchased the upper section of the island from one of Harman’s old business partners and built a stately brick home there. After years as a private residence, the island became a public leisure park in the late 1800s and then a moonshiner’s hideout in the early twentieth century. It had been abandoned for decades when West Virginia made it a state park in 1980. The state also rebuilt the mansion, which opened to the public in 1991. In 1996 the remains of Margaret and Harman Jr. were disinterred from their mausoleum in New York City and reburied beside the replica manor, close to where the original structure’s English garden once grew.

No one knows where Harman Blennerhassett’s body is. One story says he asked to be buried in the night, so there would be no witnesses. It’s impossible to prove, but maybe it was his way of escaping the trouble that followed him in life. Maybe he hoped he’d finally be able to lay low.