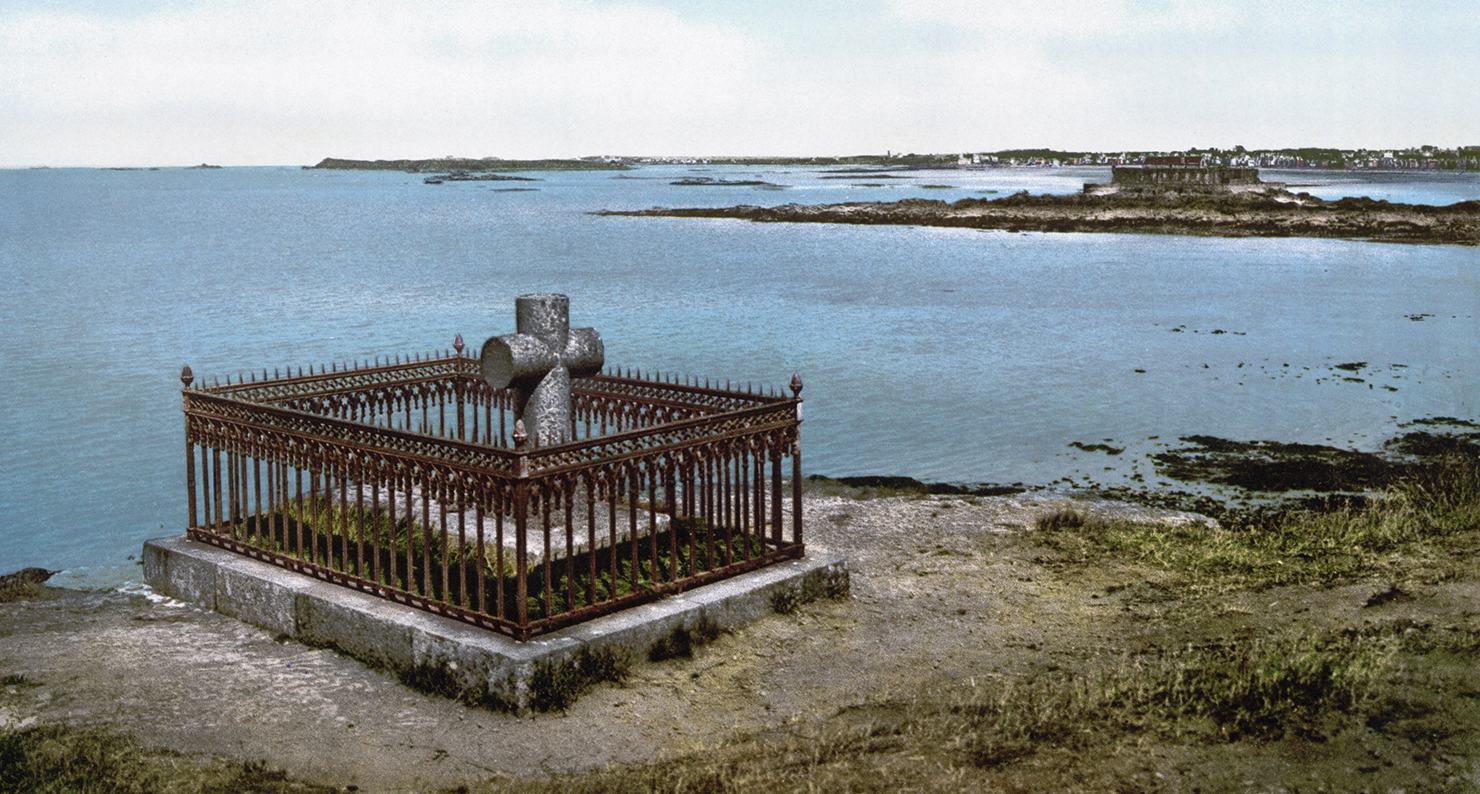

Chateaubriand’s tomb, Saint-Malo, France c. 1890–1905. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Photochrom Prints Collection.

Born in 1768 during the reign of Louis XV, François-René de Chateaubriand died in 1848, a few months after the revolution that drove Louis-Philippe from the throne and paved the way to the reign of Napoleon III. Thus did Chateaubriand straddle not only two centuries but also two worlds, that of the ancien régime and that of the modern era. He was brought up in the solitude of a medieval castle, nestled in the woods of Brittany, by a father whose nostalgia for feudal times was unremitting. At eighteen, he left his family home and enlisted as a sublieutenant in the royal army and was thrown into the vortex of the most turbulent period of French history, a span of time marked by the Revolution of 1789, the downfall of the monarchy and the execution of the king, the advent of Napoleon Bonaparte and the empire, the restoration of the Bourbon dynasty after the definite defeat of Napoleon by the powers that joined in the Holy Alliance, its overthrow by the Revolution of July 1830, the inauguration of Louis-Philippe and the establishment of the July monarchy, and finally the birth of the short-lived Second Republic.

How did Chateaubriand live through and adapt to these tumultuous times? The brutal scenes he witnessed in Paris during the first months of the Revolution shattered him, and realizing that he had to leave France, at least temporarily, he resolved to sail to America in the hope of finding the elusive Northwest Passage. Like so many others, he failed in this undertaking, but the voyage was otherwise rewarding. He discovered American democracy and, more important yet for his particular sensibility and sometimes frenzied imagination, the splendor of the wilderness of the New World. However, as soon as he heard the news of the arrest of Louis XVI at Varennes, he decided to cut his American sojourn short and return to France. There he joined the army loyal to the king, which was swiftly defeated by the revolutionary forces.

Sick and wounded, Chateaubriand took refuge in England where, like many of his compatriots, he made a meager living as a tutor and translator of French. All the while he was working on the novels that would make him famous.

Order was finally restored in France during the Consulate, and Chateaubriand concluded that it would be safe for him to return to Paris. His novels, Atala and René, brought him success and distinction and gave him reason to hope that Bonaparte would find an appropriate role for him in the new regime. But after a promising start, Chateaubriand broke with a government that was becoming more and more authoritarian, and spent the remaining years of Napoleonic rule writing and traveling. He wandered through Italy and Greece, reached Jerusalem, and came back to Paris through Spain. These journeys provided indispensable material for his later oeuvre.

Convinced that the Bourbon Restoration of 1815 would inaugurate a moderate and honorable regime, he agreed to join the new government. The publication of The Genius of Christianity had earned Chateaubriand a lasting reputation in influential Catholic circles. Louis XVIII, eager to have him on his side, named him Minister of State and later entrusted him with embassies in Berlin and London, but Chateaubriand did not have an easy rapport with the king’s entourage. “This Janus, guardian of the past and obsessed by visions of the future…too lucid, too independent, not easily deceived” (Jean-Paul Clement) was regarded with suspicion. His energetic defense of the freedom of the press finally made his resignation inevitable. The Bourbon dynasty, itself obsessed by the past, was fragile. Charles X, who succeeded his brother Louis XVIII in 1824, was ousted six years later by the Revolution of July 1830 and fled the country. Much to the disgust of Chateaubriand, the king’s cousin Louis-Philippe d’Orléans replaced Charles on the throne. Chateaubriand, who remained faithful to the legitimate branch of the Bourbons, retired from public life.

Chateaubriand was attached to the past and its centuries-old traditions, but he was also a liberal, open to modernity: this is one thing that sets him apart in the history of ideas. He had been repulsed by the discourse and the violence of the French revolutionaries and was deeply impressed by the powerful composure of George Washington, “the representative of the needs, ideas, intelligence, and opinions of his epoch.” He had a vision of social transformation that did not entail the obliteration of the past, and was proud to declare himself “Bourboniste by honor, royalist by reason and republican by inclination.”

The Memoirs from Beyond the Grave cover a lifetime. Chateaubriand claims to have begun them in 1811, but in fact the first passages of the Memoirs were written as early as 1803 or 1804. The last corrections were made in 1846. The history of the publication of the Memoirs is complicated. Financially ruined by 1836, as his resignation from the Chamber of Peers in protest against the regime of Louis-Philippe entailed the loss of practically all his income, Chateaubriand agreed to sell the rights to publication to a limited partnership that raised sufficient funds to extend to him a down payment of 155,000 francs along with the promise of an annuity of 12,000 francs for him and, should she survive him, his wife. Chateaubriand had hoped to delay publication for half a century after his death, but his new patrons, unsurprisingly, had a different schedule in mind and he had to accept a less distant date. In 1844 the society sold its rights to Émile de Girardin, the director of the newspaper La Presse, who announced that he would begin serializing the Memoirs as soon as Chateaubriand died. Though indignant, Chateaubriand was powerless to alter Girardin’s decision, so he set about enlarging and carefully revising his memoirs as a whole. Unfortunately neither the newspaper editors nor the first publishers took his changes into consideration. It was only a century later, thanks to the Pléiade edition, that French readers gained access to the correct version of Chateaubriand’s text.

The Memoirs did not enjoy an immediate success, but their appeal grew in the years after publication. Baudelaire was one of Chateaubriand’s first admirers and considered him “a master when it came to language and style”; Proust recognized his debt to the “marvelous and transcendent” artist who was the first to recognize the power of involuntary memory. Closer to us in time, General de Gaulle, after his resignation in 1946, confessed: “I don’t care about anything, I am immersed in the Memoirs from Beyond the Grave.”

The Memoirs are characterized by a striking freedom. Composed as they were over an extensive period of time, they display an unconventional and distinctive sense of chronology. Chateaubriand does not separate his life at the time he was writing from the period of the past he is describing, nor does he hesitate to insert himself into his narrative when the occasion arises. The result is a double strand: that of the events he recalls and that of the moment of composition of the narrative. “The changing forms of my life are thus intermingled,” he explained. “It has sometimes happened that, in my moments of prosperity, I have had to speak of times when I was poor, and in my days of tribulation, to retrace days when I was happy.” At one point, for example, he humorously interrupts his story: in his capacity as an ambassador, he has an urgent diplomatic question to take care of, and he begs the reader to be patient. Indeed, Chateaubriand revels in a certain insouciance, throughout his memoirs. “At the most critical and decisive moments, he turns into a dreamer and starts talking to swallows and crows in the trees along the road,” commented an irritated Sainte-Beuve.

Thus Chateaubriand will freely pass from pure reportage, for example in his closely observed description of Paris in the first months of the revolution, to introspective analyses; from historical or political considerations to lyrical evocations of nature; and from light anecdotes to carefully drawn portraits, even as he casually intersperses Greek and Latin quotations throughout. And yet for all this wide diversity, the work is meticulously constructed, which is one of the reasons why Chateaubriand was appalled at the prospect of serialization, since the cutting of the Memoirs into pieces was sure to obliterate the sense of the architecture of the whole. He may have never shrunk from a digression, but he adhered closely to the three-part plan of composition he announces at the beginning of his work, which corresponds to the principal stages of his career: soldier and traveler during the Revolution, writer during the empire, and political figure during the restoration.

From the beginning of the Memoirs, two passions emerge: for women and for politics. Though Chateaubriand observes a gentlemanly discretion, the scent of feminine presence permeates the text—from the imaginary enchantress of his adolescence to Juliette Récamier, who would become the object of his enduring adoration. And, in passing, a succession of graces is evoked: the young fisher-girl collecting tea leaves in Newfoundland; the light-footed Indian girls with “their long eyes half concealed beneath satin lids”; the modest Miss Ives who brightened his stay in England; the mercurial Delphine de Sabran of the long, blond tresses; the poignant consumptive Pauline de Beaumont, who joined him in Rome only to die in his arms; and many others who remained unnamed. The one woman who never appealed to his imagination or his senses was his wife. Unable to resist the entreaties of his mother and his sister, he had reluctantly married the eighteen-year-old Céleste de Lavigne on his return from America. The young couple was separated almost immediately by Chateaubriand’s short stint in the army and long exile in England. They were reunited twelve years later. Though Chateaubriand paid homage to the moral qualities of his wife, their life together lacked warmth and liveliness. According to Victor Hugo, Madame de Chateaubriand was stiff, ugly, charitable without being kind, witty without being intelligent. Worse than anything else she bored her husband.

Chateaubriand had taken a devouring interest in politics ever since he witnessed, as a very young man, the first assemblies of the Breton noblemen asserting their independence. Somewhat later, his observation of political life in the United States and in Great Britain, and his relief at the quelling of the revolutionary fervor during the Consulate, confirmed him in the conviction that society was subject to change. Back in Paris in 1800, after his long stay in England, he rejoiced at the reuniting of families, the reopening of churches, the return of order even when it meant that an émigré might be seen chatting with the murderers of friends and family, and concluded: “A fact is a fact…One has to take men as they are and not always see them as they are not and as they cannot be anymore.” It should be said, however, that though politics is one of the great subjects of the Memoirs, Chateaubriand himself never played an important political role. Nor for that matter does he pretend that he did. The charm and relevance of the Memoirs lie more in his constant introspection than in his scrutiny of the outside world. Chateaubriand once wrote: “It seemed to me that the apparent disorder that one finds [in my book] in revealing the inner state of a man is perhaps not without a certain charm.” The true subject of the work is a man speaking with himself.

One of the great difficulties, a difficulty admirably surmounted by Alex Andriesse, of translating the Memoirs is the wealth and the variety of Chateaubriand’s language. He turns to archaic French in the pages on his childhood in the medieval atmosphere of Brittany; he grows technical in his description of Atlantic navigation; he produces sumptuous lyrical poetry when he evokes Niagara Falls or the melancholy of Roman ruins. He has a taste for the rare word and a passion for precision. He was himself very conscious of his gift for shifting from a classical register to boldly romantic forms of expression rendered in a language so free that to men of the previous generations it appeared barbarous. His extravagance was, he claimed, always tempered by his ability to “respect the ear.”

Chateaubriand’s style reflects, as he knew, the constant tug-of-war between past and present that inspired him in many ways. He knew better than to fight these contradictions. In a draft of the preface to the Memoirs, he wrote, “Due to a bizarre fusion two men coexist in me, the man of the past and the man of today, and it happened that both the ancient French language and the modern one came to me naturally.”

The result is a glorious literary monument.

Introduction to Memoirs from Beyond the Grave, 1768–1800, by François-René de Chateaubriand, translated from the French by Alex Andriesse. Copyright © 2018 by Anka Muhlstein. Reprinted by permission of New York Review Books.