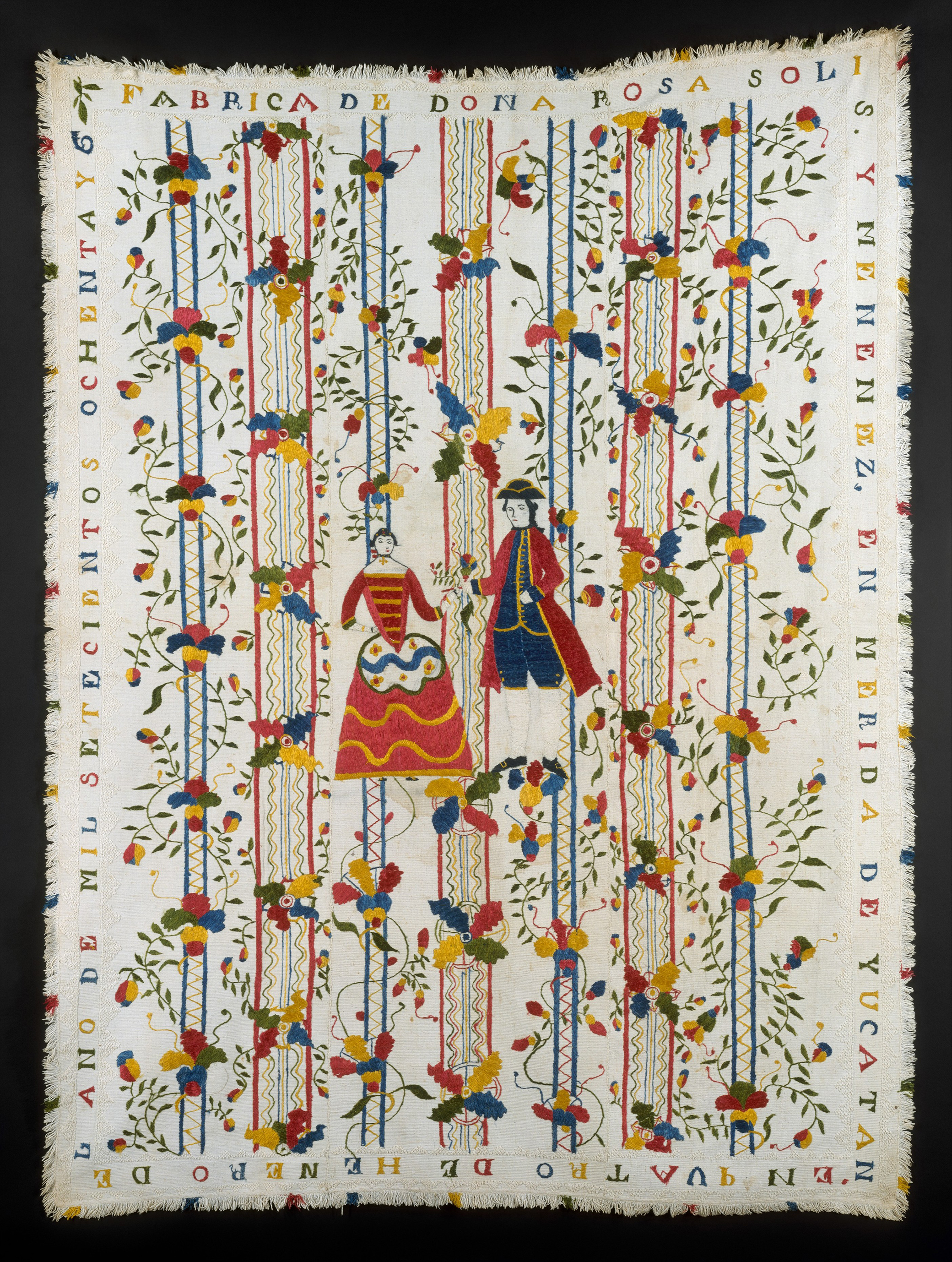

Embroidered coverlet, by Doña Rosa Solís y Menéndez, 1786. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Purchase, Everfast Fabrics Inc. Gift, 1971.

Until recently, at the bottom of my closet sat a neatly organized treasure trove of over three hundred personal letters written in the 1960s and early 1970s and exchanged among family members across the U.S.-Mexico borderlands. Written in Spanish with sprinklings of English, they contain a wealth of insight about the social, familial, and intimate relations built, sustained, and sometimes lost across the vast divide. They underscore that the decision to immigrate to the United States was not without personal and emotional pain, although it could also elicit excitement and eager anticipation. Indeed, migrating invited a host of challenges as well as rewards. The writings depict longing, isolation, and restlessness living between here (aqui) and there (allá) and demonstrate moments of discovery, deep satisfaction, and joy in having made the move, albeit often temporarily. They reveal, too, the creative coping mechanisms and cultural resources migrants devised, adapted, and drew upon to negotiate the daily reality of living relatively alone and facing a host of gender, racial, ethnic, class, and cultural constraints in the new environment.

Like all sources, the letters are biased, inconsistent (some are missing, undated, illegible, incomplete, or penned sporadically), manipulative, formulaic, and mundane. Without a richly textured historical framework animating and breathing life into them, the missives are anecdotal, irrelevant, and cut off from the ebbs and flows of that region of the globe.

My effort to make meaning of the letters began in 2012, shortly after my tío Paco, my father’s youngest brother, who raised me and my only brother, rediscovered the letters and placed them in my hands. My uncle had found the letters in the basement of his house, where they had been stored ever since my brother and I had moved into his home and that of his wife, Beatríz Chávez, in 1981, after a horrific car accident early that year, on our way home from Mexico, took the lives of my parents and my paternal grandmother. My brother and I, who were thirteen and twelve years of age, respectively, were also in the wreck but fortunately survived with few serious injuries. In the process of adjusting our lives to the new household, we got rid of most of my family’s belongings, save for family albums, heirlooms, and random knickknacks. Thankfully, we hung onto the surviving eighty letters my parents had exchanged: forty-five from my father written in the United States, thirty-five from my mother based in Mexico.

At the heart of the communication was my father’s desire to court and eventually wed my mother, whom he had met briefly in December 1962 during one of his visits home to Mexico during the holidays. At the time, my father was a single, thirty-year-old farmworker in Imperial Valley, one of California’s most productive agricultural zones, situated across the border from the Mexicali Valley in Baja California, Mexico. He had migrated there a few years earlier, in 1957, as a means of surviving the growing impoverishment of the Mexican countryside, despite the purported gains of Mexico’s rapid industrialization, modernization, and integration into the global economy in during World War II and the postwar era. Rather than face bleak prospects in his pueblo or try his luck in Mexico City, as many rural Mexicans did, he took advantage of the employment opportunities offered by the bracero program. A contract-labor importation accord negotiated through a series of agreements between Mexico and the United States, the bracero program was initiated as a wartime strategy for the northerly neighbor’s need for inexpensive agricultural workers. Launched in 1942 as part of the effort to ease a so-called labor shortage in farmwork resulting from World War II and, later, the Korean War, that program would go on to last for twenty-two years, until 1964, after repeated calls for the continued need and desire for a cheap (read: controllable and dispensable) labor force. Mexico benefited, too, because the program relieved some of the poverty and misery in the rural zones and in the growing urban areas through the employment of landless Mexican males in el norte as well as through remittances (remesas). As early as the 1950s, according to Deborah Cohen, remittances made up “Mexico’s third-largest source of hard currency.” By the late 1970s, remesas would serve as an increasingly indispensable component of Mexico’s sources of foreign income. Agricultural interests south of the border were not always satisfied with the accord, however, as they decried the loss of Mexico’s greatest resource: labor.

By the time José began his campaign to win Conchita’s heart and hand in marriage in the early 1960s, the “Mexican Miracle” of rapid economic development and growth as well as rising agricultural productivity in Mexico was at its peak. Yet for José and the Mexican men like him who enrolled in the bracero program, the miracle was a mirage.

The presence of letters does not, of course, mean that they are complete interpretations of a particular moment that we can piece together like a puzzle. Many purposely withheld or filtered information, resisting full disclosure as well as a complete understanding of the evolution of the relationship. Doing so was not always accidental, for it allowed letter writers the ability to escape censure and reprimand from their intended audience, particularly when they made decisions that contradicted family advice. It afforded them the opportunity to avoid sympathy and pity when their migratory plans went awry. Not writing, remaining silent, and failing to reveal the intensity of the pain and loneliness they experienced as a consequence of their migration and isolation in a new and foreign land also enabled them to protect loved ones who stayed at home. To whom, when, and why they chose to disclose information or withhold it is equally significant and says a lot about how they structured their personal, familial, and social lives across the border. While some attempted to keep their intimate, personal relations in el norte separate from their household and peer relations back home, the tight-knit family and social networks in the pueblo and free exchange of chisme often made that nearly impossible.

Understanding my role in the process of writing my family’s history and my relationship to the sources, that is, my subjectivity, has been a constant preoccupation in crafting this study. Admittedly, my desire to recover the lives and legacies of my parents, who died when I was a twelve-year-old girl, was the initial motivation for carrying out this project. I now realize that by holding, reading, and, later, transcribing, translating, and interpreting their words, I had tricked myself into believing that I could bring them back to life, or at least get to know them, in their youth, the way I was never able to do in real life. I now realize that the letter-writing process, which I had come to rely on as a medium or mechanism for rendering and reconnecting with them, is an imperfect séance, as are all source materials, including oral histories, census records, and government reports, which also suffer from manipulations, silences, and distortions. Nevertheless, the correspondence has proved a rich and unparalleled source, a relatively untapped window for mining the experiences of Mexican migrants and the relations they developed, sustained, and experienced in a larger social network and historical context.

From Migrant Longing: Letter Writing Across the U.S.-Mexico Borderlands by Miroslava Chávez-García. Copyright © 2018 by the University of North Carolina Press. Used by permission of the publisher.