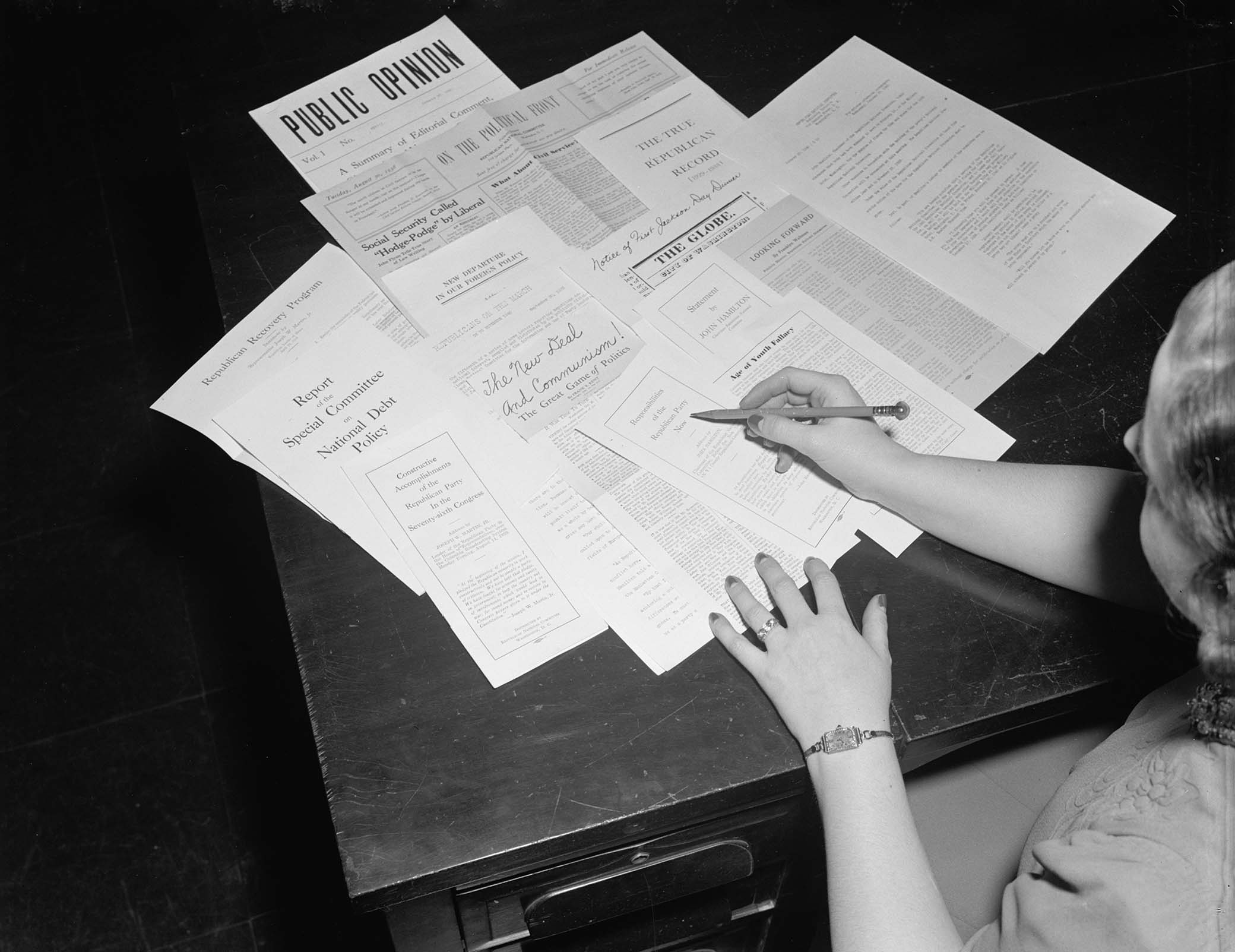

Releases of the Republican National Committee’s Press Relations Department, c. 1939. Photograph by Harris & Ewing. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

National Review and its sister magazines had several functions for the growing conservative movement: they provided a medium for identity formation, places to collaborate on ideas and strategies, and sites to build discursive prose that challenged popular opinion. Editorials triggered affective responses from readers without regard for empiricism. It did not matter whether the reporting that readers received was true, or whether the editorials were based in expert opinion, so long as the content resonated with consumers searching for common cause between the pages. Conservative writings were, as scholar Steven Selden explains, “designed for affiliation, not clarification.” Accordingly, the conservative countersphere could be used to “inoculate” consumers “against ideology-contradicting facts and arguments.”

Writers building the conservative countersphere directed college students in their charge to follow suit. Because university-sponsored newspapers were perceived as tinged with the common academic and media afflictions of liberalism, the students needed to create alternative periodicals modeled on their national examples. Even more alarming, Morton Blackwell, executive director of the College Republican National Committee (CRNC) from 1965 to 1970, was explicit in stating that his students were behind on this critical “technology” that the New Left had already mastered. If the Right could figure out how to operate like left-wing groups’ “underground” papers, independent of the campus press, then their content would not be beholden to administrative oversight. With this relative subject-matter freedom, the Intercollegiate Studies Institute (ISI)— created in 1953 by writers at the Freeman and Human Events magazines and bankrolled by the William Volker Fund as a foil to the Intercollegiate Socialist Society—supplied students with ideas from the national office and conservative magazines, such as National Review, Human Events, Modern Age, and Public Interest. As Blackwell recalled, the Foundation for Economic Education gave a free subscription of its journal, the Freeman, to any college student who requested one.

ISI regional directors helped connect students at different campuses within their districts to share publishing resources from the national organization. Student journals included Yale’s Alternative, the Harvard Conservative, the University of Wisconsin’s Insight and Outlook, the University of Chicago’s New Individualist Review, and the University of Missouri’s Conservative Digest. ISI’s own publication, the Intercollegiate Review, claimed a readership of 45,000 by 1967.

At the University of Mississippi, the Young Americans for Freedom (YAF)’s Granite included a regular feature called Faculty Follies dedicated to exposing errors (or supposedly errant political claims) made by their professors. One section, Words to Remember, offered praise for Chancellor Porter Fortune’s harsh condemnation of campus radicals. The column promoted the ideas of writer Morrie Ryskind, a member of its national advisory board. An accompanying section, Words Not to Remember, provided disparaging quotes from “Very Liberal Professors.” In columns titled Problems on the Left and Answers on the Right, YAFers characterized liberals as unbathed and offered the following solution: “On that feud among our faculty comrades, we suggest an extended field trip to the Sino-Soviet border so they can aid and abet their cause. As for our unwashed stinkers, perhaps they should seek treatment at [Mississippi psychiatric facility] Whitfield.”

YAF’s bimonthly Free Campus News Service supplied pictures, columns, news releases, cartoons, and other copy to student editors in need of content. YAF’s national headquarters disseminated Do It! On Publishing a Conservative Underground Newspaper, a how-to manual addressing finances, content creation, hiring staff, and distribution—something start–up underground papers desperately needed. CRNC leaders also produced multiple guides and primers: Club Newsletters, How to Prepare a Club Newsletter, Communications, and even an instructional pamphlet titled Possibilities for Propaganda.

When students needed content, editorial advice, or donations, they had a host of mentors in the literary world to turn to: publisher Henry Regnery, YAF founder M. Stanton Evans at the Indianapolis Star, and especially the staff at National Review and Human Events. Often student editors short on ideas penned biographical and political profiles of benefactors and advisory board members like Morrie Ryskind and Joseph Coors. In this way, the students could fill editorial space while currying favor with their movement leaders and advertising their donors’ businesses.

Not only did they need to promote their sponsors, executives were more concerned with the students’ management of their own image. It is striking how often the College Republican newsletter manual directed students to use their writing space to defend themselves from other conservatives’ insults and negative characterizations. Regarding content production, the first instruction was that the newsletter provide a record of College Republicans’ work. The manual specified that doing so was paramount in “visibly refuting the charge ‘The CRs don’t do anything.’”

The second instruction was to use the newsletter to push ideology: “It should be a vehicle for waging ‘ideological struggle’—that is, a way to make known the Republican stance on important issues…to convince the uncommitted.” If they needed ideas, students were encouraged to “lift” articles from the Republican National Committee’s newsletter First Monday, the CRNC’s College Republican, or the Republican Congressional Committee’s newsletter. Editorials should be written on local matters, such as the state education budget, student housing and parking, and any other “good biting topics.”

Though CRNC officials directed student writers to use editorials to advance a partisan ideological edge, they cautioned student journalists not to pander too much: “Any attempt at cuteness or an overly ‘feature’ style…is fatal.” Campus readers expected a certain mature voice and satisfying that expectation would make the publication more trustworthy and believable. Blackwell underscored that “students appreciate cleverness but react negatively to unfairness.” CRNC officers still believed attention to style mattered: “Do not ignore the power of humor. Use cartoons, funny pictures, or anything that cast the opposition in a ludicrous light. Don’t get caught taking yourself too seriously.”

As with most conservative youth group efforts, the magazines were largely funded by approving alumni and concerned local business owners. At Indiana University, the Alternative’s fundraising letters asked for donations in the name of “the efforts of responsible Indiana University students” working against the “doctrines of anarchy and revolution” on their campus. These funds helped keep subscriptions relatively affordable. The Alternative sold its first issue in September 1967 for 15 cents. An annual subscription to the monthly Carolina Renaissance, co-published by students at Duke University and the University of North Carolina and subtitled “News and opinions suppressed by the campus press,” could be purchased for $2.50.

The Alternative, the most successful and long-lasting of these student papers, is still operational today through generous right-wing sponsorship. R. Emmett Tyrrell Jr. and Stephen Davis founded the magazine with a $3,000 donation (worth over $27,000 in 2023) from the Lilly Endowment, a private Christian philanthropy. As historian Daniel Spillman notes, its writers had “a penchant for cruel, ad hominem attacks” on their campus rivals. Alongside vicious editorials, the magazine also featured opinion articles from highly regarded conservative scholars like Irving Kristol and Sidney Hook. A $25,000 donation from billionaire Richard Mellon Scaife in 1970 (worth approximately $200,000 in 2023) enabled the campus-based publication to go national. Consistent donations from Scaife and the Lilly Endowment exceeded well over $1 million throughout the 1970s.

Today, the Alternative is still in online publication as the American Spectator. However, this is an exception. Unlike progressive or radical underground papers, there is little indication that other conservative circulars lasted past their founders’ graduations. The only other known campus conservative magazines from the 1960s still in existence are the University of Wisconsin’s Badger Herald (which is no longer conservative) and the libertarian Reason, created by Boston University student Lanny Friedlander from his dorm room in 1968.

During the Nixon administration, College Republican clubs greatly expanded and professionalized conservative campus news and radio with explicit direction from the White House and GOP advisers. A small number of students were doing the lion’s share of marketing conservatism on campus to bridge the divide between Richard Nixon’s administration and young people.

And while Nixon was personally uninterested in courting youth organizers, some among his staff were, including YAF executives Tom Charles Huston and Pat Buchanan. By building close relationships with college editors and radio hosts, Nixon could ensure that coverage of his administration became less inflammatory.

At the invitation of White House staff, Morton Blackwell and College Republican chair Robert Polack met with Nixon advisers to discuss how the administration could better sell itself on campus. The pair proposed a news service to broadcast updates directly from the White House, bypassing established campus news agencies like the College Press Service (CPS), which was often critical of the administration. Nixon’s communications staff provided a list of college newspapers and radio stations and the addresses of current White House interns, noting that they would be “good contacts” for them. They also offered to provide content and financial assistance for the first mailing. Shortly thereafter, the Washington Campus News Service (WCNS) was delivering partisan news releases to the same campus editors and radio broadcasters who received critical pieces from the CPS.

The GOP duplicated this strategy at the state level with its State Campus News Service, designed to “pay big dividends for both the College Republicans and the Republican Party.” The operation was “staffed, produced, and funded by the College Republican Federation,” and its goal was to “inundate the campus media with Republican-oriented materials.” A group of six students responsible for a state territory “manufactured” news releases (with instructions to “be bold”), radio releases, fact sheets, and backgrounders for cover articles, and five–minute taped interviews with GOP members. To build relationships and curry favor, College Republicans were directed to “court” local news stations: “Call them, prod them, be nice to them, and ask their advice.”

Then, to soften relations with the often critical CPS, Nixon’s communications office contacted its editors directly to discuss ways the White House could help provide content through press and radio releases. Though the CPS was opposed to the administration’s policies, the liaison benefited Nixon in that his speeches and other messages would be delivered directly to any campus newspaper or radio station whether or not they received CPS or WCNS materials. Nixon staff issued official White House press credentials to both CPS and WCNS student reporters and extended invitations to regular press briefings—privileges denied by prior administrations. Before long, the CPS and the WCNS were receiving exclusive articles by cabinet members and others in the Nixon presidency, with the WCNS distributing biweekly reports directly from the White House.

In its Possibilities for Propaganda memo, the CRNC instructed campus chapters to use WCNS releases in their own club newsletters, urging members to create a View from Washington column that summarized several of the WCNS releases in one meaty article. They were also supposed to forward WCNS releases to their own campus newspapers and radio stations in order to reach audiences that did not read College Republican materials. Students kept a file of releases to build a database of details they could use to write counter-editorials in campus and town newspapers, arming themselves with “the facts” to put “a Republican slant on things.” Doing so was important, Blackwell urged, not just for building up credibility but to show that “CRs do do something!”

Nixon staff directed the WCNS to issue reprints of friendly articles from movement magazines to its college editors and broadcasters, offering to have the Republican National Committee’s Communications Division cover the distribution costs, despite the students’ $30,000 annual operations budget (equivalent to approximately $260,000 in 2023). By 1972 the WCNS claimed to issue weekly reports to 1,700 campus newspapers, 400 campus radio programs, and 450 College Republican chapters. However, internal CRNC memos show that the WCNS had insufficient funds to continue its operations beyond that point. Nixon and his staff also would not remain in the White House much longer for their propaganda to be necessary.

The short-lived direct-from-the-White-House news service inspired Nixon media consultant Roger Ailes to create a television news version. A memo, “A Plan for Putting the GOP on TV News,” circulated between Ailes, White House chief of staff H.R. Haldeman, and others, outlining a proposal to create pro-Nixon videotapes to distribute to local television news stations as free programming. The estimated $542,000 start-up investment and annual expected operating cost of $167,000 would be covered by the GOP. The plan entailed recording video content (such as a GOP senator’s speech), editing out forty-second-to-one-minute clips, and reproducing at least forty copies of the tapes. The videos would be flown from Washington, DC, and delivered to stations representing the top television markets in the country: New York, Los Angeles, Chicago, Philadelphia, Boston, and thirty-five other cities.

Though the Capitol News Service, as it would have been called, never got off the ground, it served as a clear blueprint for the right-wing Television News Inc., founded in 1973 by Paul Weyrich and bankrolled by Joseph Coors, and for Ailes’ Fox News in 1996.

From Resistance from the Right: Conservatives and the Campus Wars in Modern America by Lauren Lassabe Shepherd. Copyright © 2023 by Lauren Lassabe Shepherd. Used by permission of the University of North Carolina Press.