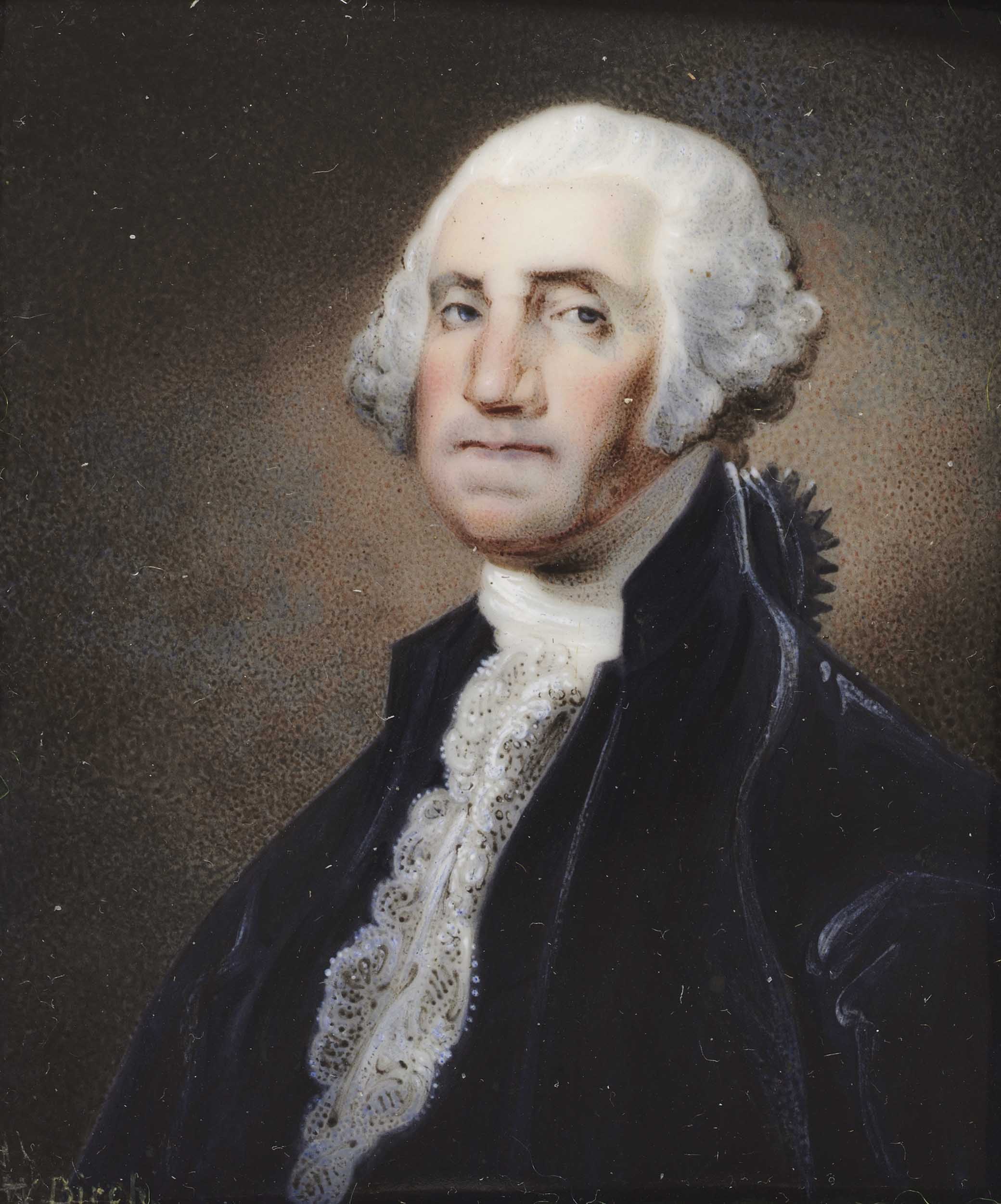

George Washington, by William Russell Birch, c. 1790. The Cleveland Museum of Art.

When the London newspaper the Athenian Mercury, edited and published by the author and bookseller John Dunton, first answered questions about romance, bodily functions, and the mysteries of the universe in 1691, it may have created the template for the advice column. But the history of advice stretches back even further into the past. Advice—whether unsolicited, unwarranted, or desperately sought—appears in ancient philosophical treatises, medieval medical manuals, and countless books. Lapham’s Quarterly is exploring advice through the ages and into modern times in a series of readings and essays.

In November 2022, Elon Musk tweeted a photograph of his bedside table, decorated with four cans of caffeine-free Diet Coke, a small framed print of Washington Crossing the Delaware, and a replica of one of George Washington’s pistols, among other items. Hidden behind a water bottle was a third item related to Washington, later revealed, in yet another tweet, to be a red, white, and blue bound collection of three texts: the Declaration of Independence; the U.S. Constitution; and The Rules of Civility and Decent Behaviour in Company and Conversation, a 1744 compilation of advice by the future first president. Like many collections of advice, it was mostly plagiarized or at least far from original. The thirteen-year-old Washington likely was asked to copy the rules, as part of a penmanship lesson, from a 1640 English translation of sixteenth-century rules formulated by French Jesuits. (His handwriting, at least from a twenty-first-century perspective, looks rather precocious.) He may have adapted some of the rules to appeal to teenage sensibilities.

Joseph M. Toner, a Washington, DC, doctor and prolific publisher of Washington’s words, released an edition of The Rules of Civility in 1888, hoping that “the original manuscript may prove not only gratifying to American pride but be of benefit to the growing youth of our country.” He also addressed the questionable authorship:

It is proper to state that nearly all the principles incorporated and injunctions given in these 110 maxims had been enunciated over and over again in the various works on good behavior and manners prior to this compilation and for centuries observed in polite society. It will be noticed that, while the spirit of these maxims is drawn chiefly from the social life of Europe, yet, as formulated here, they are as broad as civilization itself, though a few of them are especially applicable to society as it then existed in America, and, also, that but few refer to women. The latter fact may possibly be accounted for by the youth of the author.

Below is a sampling of the young George Washington’s dicta.

When in company, put not your hands to any part of the body not usually discovered.

In the presence of others, sing not to yourself with a humming noise, nor drum with your fingers or feet.

If you cough, sneeze, sigh, or yawn, do it not loud but privately; and speak not in your yawning but put your handkerchief or hand before your face and turn aside.

Sleep not when others speak, sit not when others stand, speak not when you should hold your peace, walk not on when others stop.

Spit not in the fire, nor stoop low before it; neither put your hands into the flames to warm them, nor set your feet upon the fire, especially if there be meat before it.

Shake not the head, feet, or legs; roll not the eyes; lift not one eyebrow higher than the other; wry not the mouth; and bedew no man’s face with your spittle by approaching too near him when you speak.

Do not puff up the cheeks, loll out the tongue, rub the hands or beard, thrust out the lips or bite them, or keep the lips too open or too closed.

Read no letters, books, or papers in company, but when there is a necessity for the doing of it, you must ask leave; come not near the books or writings of another so as to read them unless desired or give your opinion of them unasked; also look not nigh when another is writing a letter.

Do not laugh too loud or too much at any public spectacle.

Let your discourse with men of business be short and comprehensive.

Artificers and persons of low degree ought not to use many ceremonies to lords or others of high degree but respect and highly honor them, and those of high degree ought to treat them with affability and courtesy, without arrogance.

In speaking to men of quality, do not lean nor look them full in the face, nor approach too near them; keep at least a full pace from them.

In visiting the sick, do not presently play the physician if you do not know therein.

When a man does all he can though it succeeds not well, blame not him that did it.

Mock not nor jest at anything of importance, break no jest that is sharp biting, and if you deliver anything witty and pleasant, abstain from laughing thereat yourself.

Wear not your cloths foul, ripped, or dusty but see they be brushed once every day at least and take heed that you approach not any uncleanness.

Run not in the streets, neither go too slowly nor with mouth open, go not shaking your arms, kick not the earth with your feet, go not upon the toes, nor in a dancing fashion.

Play not the peacock, looking everywhere about you, to see if you be well decked, if your shoes fit well, if your stockings sit neatly and cloths handsomely.

Eat not in the streets, nor in the house, out of season.

Speak not of doleful things in a time of mirth or at the table; speak not of melancholy things as death and wounds, and if others mention them, change if you can the discourse; tell not your dreams but to your intimate friend.

Break not a jest where none take pleasure in mirth; laugh not aloud nor at all without occasion; deride no man’s misfortune, though there seem to be some cause.

Reprehend not the imperfections of others, for that belongs to parents, masters, and superiors.

Gaze not on the marks or blemishes of others and ask not how they came. What you may speak in secret to your friend deliver not before others.

While you are talking, point not with your finger at him of whom you discourse, nor approach too near him to whom you talk, especially to his face.

Be not tedious in discourse or in reading unless you find the company pleased therewith.

Being set at meat, scratch not; neither spit, cough, or blow your nose except when there’s a necessity for it.

Make no show of taking great delight in your victuals, feed not with greediness, cut your bread with a knife, lean not on the table, neither find fault with what you eat.

Take no salt or cut bread with your knife greasy.

If you soak bread in the sauce, let it be no more than what you put in your mouth at a time and blow not your broth at table but stay till it cools of itself.

Drink not nor talk with your mouth full; neither gaze about you while you are drinking.

Drink not too leisurely nor yet too hastily. Before and after drinking, wipe your lips; breathe not then or ever with too great a noise, for it is uncivil.

Be not angry at the table whatever happens, and if you have reason to be so, show it not; put on a cheerful countenance, especially if there be strangers, for good humor makes one dish of meat a feast.

If others talk at the table, be attentive but talk not with meat in your mouth.

Labor to keep alive in your breast that little spark of celestial fire called conscience.

Read the other entries in this series: Inez Milholland and Eugen Boissevain, Plutarch, Lewis Carroll, Chrétien de Troyes, Yan Zhitui, Nizam al-Mulk, Saadi, Giovanni Della Casa, Maria Edgeworth, Dan McQuade on basketball manuals, and Leopold Froehlich on syndicated advice columnists.