Hector Taking Leave of Andromache, manner of Angelica Kauffman, eighteenth century. Photograph © Tate (CC-BY-NC-ND 3.0).

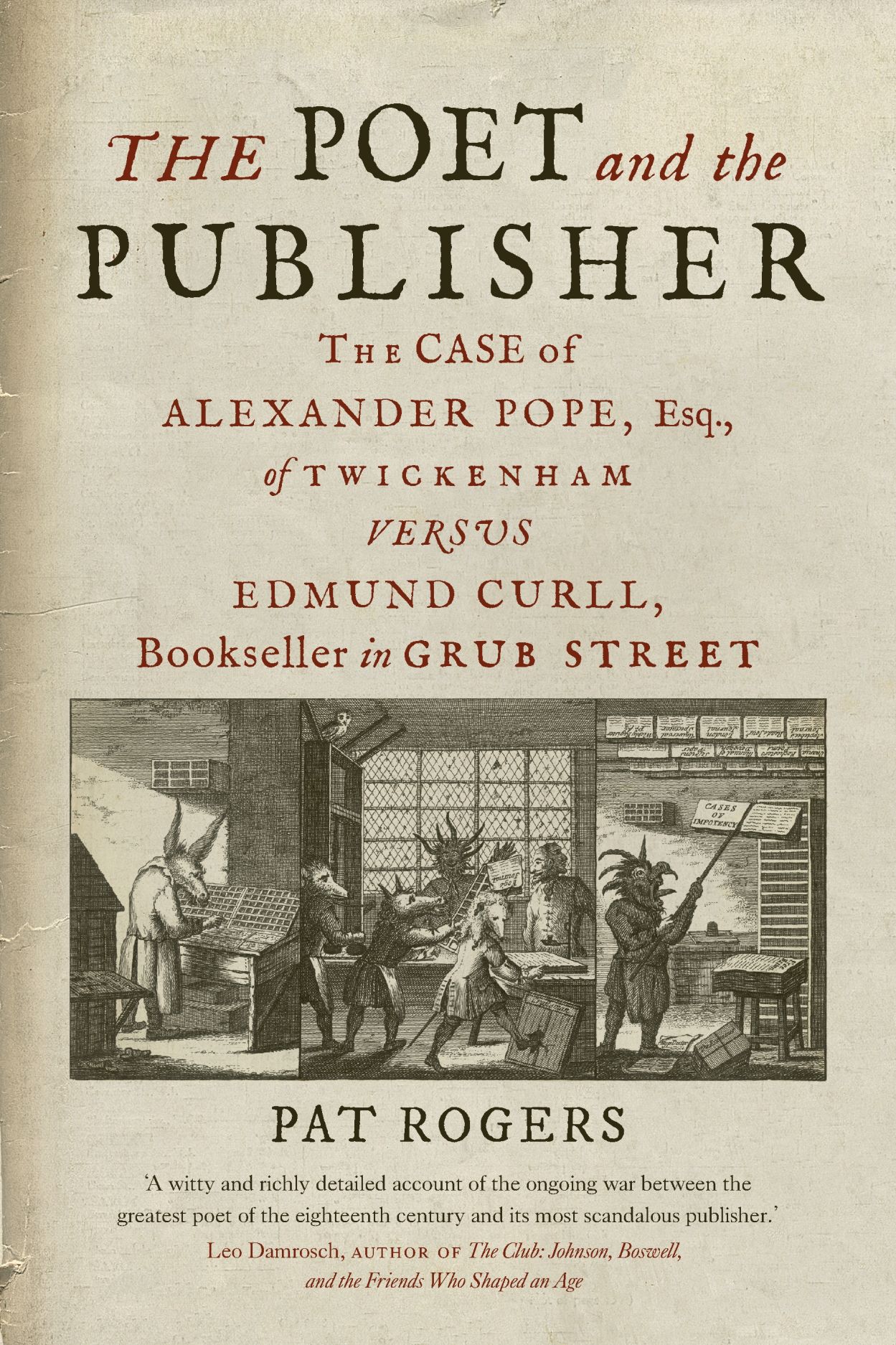

We may wonder what got the quarrel started between the poet Alexander Pope and Edmund Curll, a London bookseller churning out mostly ephemeral publications. Hardly anybody outside Britain would have heard of him. Many of his methods—which often included unauthorized piracy of works—were downright illegal, and he did not belong to the respected Company of Stationers, charged with keeping up the good name of the trade. Late in the course of their quarrel, Curll visited Pope’s Thames-side home without permission, and brought out an illustrated description of the house and garden. Pope had reached the pinnacle of literary renown; Curll had merely been elevated to the pillory for offenses including sedition and obscene publications. In Pope’s case, Curll not only pirated the poet’s works, he also frequently provoked the writer’s ire by publishing satirical criticisms of his output and politics.

The publisher had already antagonized some prominent writers. At the head of this list comes Jonathan Swift, an acquaintance of Pope and a figure who had achieved considerable fame as a satirist and political polemicist. Curll had purloined some unpublished manuscripts, which he issued to the world in 1710 together with a key explaining the occasion and meaning of Swift’s great Tale of a Tub, which had first come out in 1704. This was the start of a decades-long campaign to unearth items by Swift (genuine or spurious), and bring them before the public whether or not the writer had given permission. This task would be made easier as time went on by the absence of a proper copyright agreement between London and Dublin, the city where most of Swift’s new works appeared after he was made Dean of St. Patrick’s Cathedral in 1713. Small wonder that Swift complained in May 1711 to his Dublin friends, “That villain Curl has scraped up some trash, and calls it Dr. Swift’s miscellanies, with the name at large, and I can get no [legal] satisfaction of him.” It would not be the last time the bookseller got away with piracy.

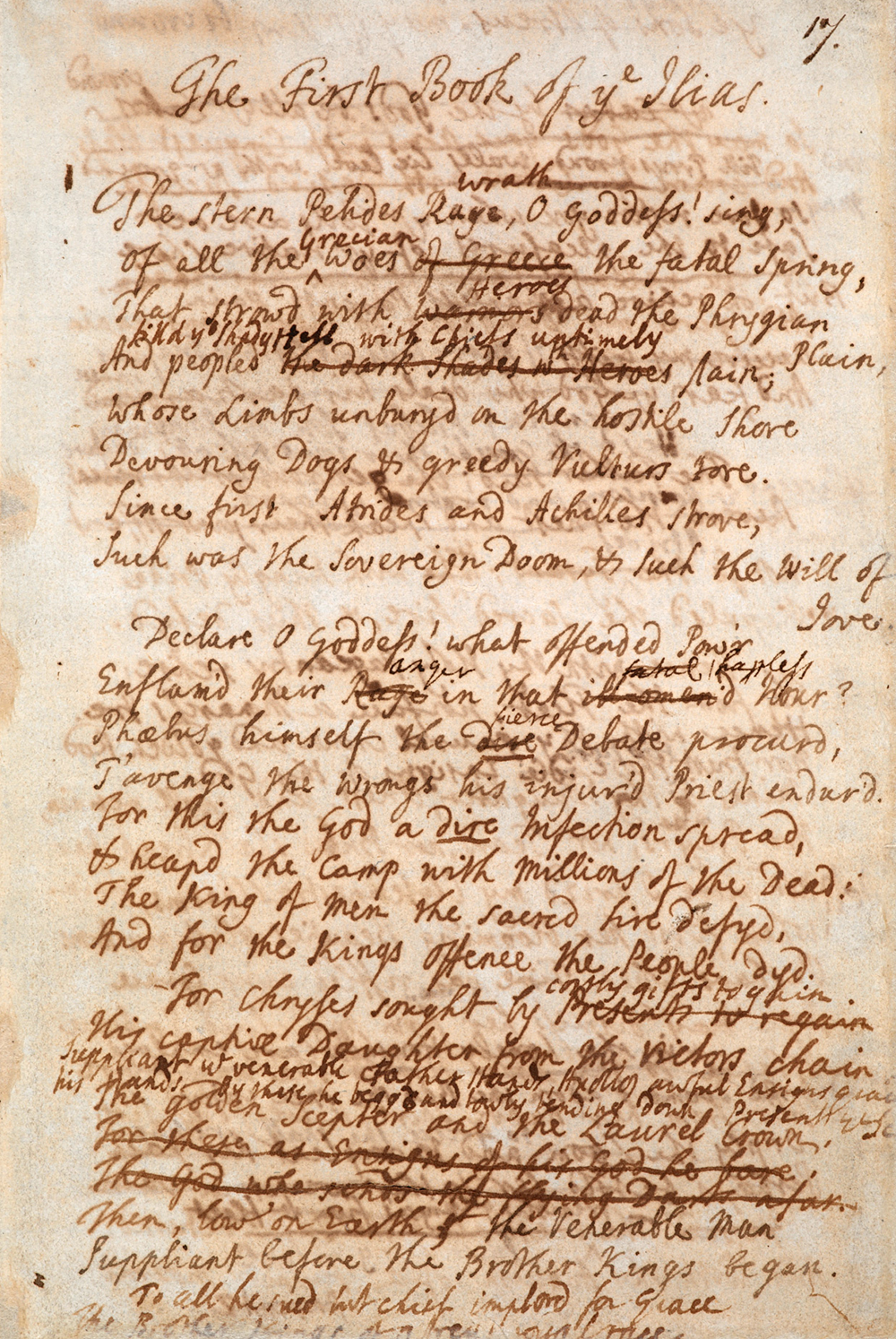

Pope himself had just burned his boats. This happened on March 23, 1714, when he contracted with publisher Bernard Lintot to translate the Iliad. This remarkable agreement provided the author with privileges never enjoyed before by an English writer. Among other things, the publisher consented to Pope’s choosing the font and the printer’s ornaments. He let the poet have 750 copies for subscribers, and withheld from the market the trade copies for his own benefit until these had been disposed of. Most startling of all, Lintot assented to a financial deal of great generosity: he would pay two hundred guineas for each volume as copyright money. Half of this would be paid in advance, and the remainder on delivery of the copy. It is estimated that the author would clear a total of £1,290 copyright money, and £4,837 from the sale of “his” 750 copies of each volume.

These are sums that would have made Midas blush. The project became generally known because proposals were issued to attract subscribers, taking this form:

Proposals for printing, by subscription, a translation of Homer’s Iliad into verse and rhyme. By Mr. Pope. To which will be added, explanatory and critical notes; wherein the most curious and useful observations, either of the ancients or moderns, in relation to this author in general, or to any passages in particular, shall be collected and placed under their proper heads.

This Work shall be printed in six volumes in quarto, on the finest paper, and on a letter new cast on purpose; with ornaments and initial letters engraven on copper. Each volume containing four books of the Iliad; with notes to each book. It is proposed at the rate of one guinea for each volume; The first volume to be delivered in quires within the space of a year from the date of this proposal, and the rest in like manner annually; Only the subscribers are to pay two guineas in hand, advancing one in regard of the expense the undertaker must be at in collecting the several editions, critics and commentators, which are very numerous upon this author.

A third guinea was payable to Lintot by subscribers on the delivery of each volume. By the end of the year the venture had proceeded so far that Pope could advance the date for publishing the first volume to March 1715. Long before that, however, the cavils had started to come in. In the previous April, almost before the ink on the contract was dry, a writer named Charles Gildon added “a word or two upon Mr. Pope’s Rape of the Lock” to his critique of the plays of Nicholas Rowe, entitled A New Rehearsal. Gildon had also been involved in Curll’s edition of the poems of Shakespeare in 1709, and a year later had produced a life of the actor Thomas Betterton (one of Pope’s early mentors), of which Curll was copublisher. He went on writing for the bookseller over a number of years, most significantly with a collection of Memoirs of William Wycherley (1718), devoted to a writer who played a key role in Pope’s literary evolution as a young man. Pope complained that Gildon had abused him “very scandalously” in this work. This is our first meeting with a man who was one of a small army of professional authors who slaved away for Curll. As with most of this group, Gildon scarcely has a name to conjure with today.

It is understandable that the sensitive Pope took umbrage at what he found in the New Rehearsal. The dialogue is set in a Covent Garden tavern, with an easily identifiable young poet named Sawney Dapper characterized as “one of the most empty and most conceited of the whole tribe.” The criticism soon deflects from The Rape of the Lock to Pope’s recently announced plans for the Iliad version. Sawney boasts that he has the Greek poets lying on his hands “for a translation.” This provokes a comment by the bland raisonneur, Sir Indolent Easie. Sawney replies, “Why…if I did not understand Greek, what of that; I hope a man may translate a Greek author without understanding Greek…Ah! Sir Indolent, you don’t know half the arts of getting a reputation in this town for learning and poetry.”

In the same month came an episode that has been seen as an “offense against Pope,” which stands near the beginning of Curll’s “lifelong quarrel” with the poet. It relates to a volume entitled Poems and Translations. By Several Hands. The offensive material consists of the inclusion under Pope’s name of a rather childish though clever item of seven lines, “A Receipt [Recipe] to Make a Cuckold.” This had come out in the previous year, but the author then suppressed it, or tried to. Pope told John Caryll—a lifelong intimate friend, dedicatee of The Rape of the Lock, and godfather of Martha Blount—that the lines had been “stolen” from him.

A Receipt to make a Cuckold.

By Mr. POPE.

Two or three Visits, and two or three Bows,

Two or three Civil Things, and two or three Vows;

Two or three Kisses, and two or three Sighs,

Two or three Jesu’s and Let me Dye’s;

Two or three Squeezes, and two or three Towzes,

Two or three Hundred Pounds lost at their Houses,

Can ne’re fail Cuckolding two or three Spouses.

“Towzes” here means affectionately rough horseplay. Bearing in mind the brevity of the text, the author’s name could hardly be blazoned much more conspicuously.

Later in the volume we encounter lines addressed “To Mr. Pope, on His Intended Translation of Homer’s Iliads.” By the standards of the attacks to come, this was not a wholly unfriendly allusion to the money that the translator, unlike his source in the ancient world, would be making from his project. The author was the librettist John Hughes, with whom Pope generally got on well. This was one of the first unsolicited admonitions the poet would receive:

Advice to Mr. Pope,

On his Intended Translation of Homer’s Iliads

O Thou, who with a Happy Genius born,

Can’st tuneful Verse in flowing Numbers turn,

Crown’d on thy Windsor’s Plains with Early Bays,

Be early wise, nor trust to barren Praise.

Blind was the Bard that sung Achilles’ Rage,

He sung and begg’d, and curs’d th’ ungiving Age;

If Britain his translated Song wou’d hear,

First take the Gold—then charm the list’ning Ear,

So shall thy Father Homer smile to see

His Pension pay’d, tho’ late, and pay’d to Thee.

Pope had good reason to believe that Curll was responsible for this affront.

Another offense would have passed by most observers, though not Pope. In his unauthorized collection of the poems of Nicholas Rowe, Curll inserted a risqué little item entitled “On a Lady Who P---st at the Tragedy of Cato.” It concerns the reactions of a Tory lady named Celia who sat dry-eyed at the big stage hit of the year, Joseph Addison’s Cato, a high-minded (and, to most modern tastes, highly uninteresting) tragedy that had been claimed by the Whigs as a defense of English liberty.

On a Lady who P---st at the tragedy of Cato

While maudlin Whigs deplor’d their Cato’s Fate,

Still with dry Eyes the Tory Celia sate,

But while her Pride forbids her Tears to flow,

The gushing Waters find a Vent below:

Tho’ secret, yet with copious Grief she mourns,

Like twenty River-Gods with all their Urns.

Let others screw their Hypocritick Face,

She shews her Grief in a sincerer Place;

There Nature reigns, and Passion void of Art,

For that Road leads directly to the Heart.

The piece was not assigned an author, and it remains unclear what share Rowe and Pope took respectively in its composition. More than a decade later Pope allowed it to appear in the Miscellanies compiled by his friends and himself. But by that time Curll had reprinted it four times, most recently with the title bowdlerized for polite ears as “A Lady Who Shed Her Water.” Another version substituted “A Tory Lady Who Happen’d to Open Her floodgates.”

From this time Curll adopted a plan with regard to Pope’s works. If he could not claim the ownership of a major poem, he would find a way to profit from its success by concocting some kind of spin-off volume. This happened in early 1714. On March 2 Lintot published The Rape of the Lock in five cantos, an expansion of the much briefer version issued two years earlier. It took very little discernment to see immediately that this was an extraordinary achievement, likely to echo down the ages as one of the greatest satires in the language. In less than a fortnight the author could report to John Caryll that the Rape had sold three thousand copies within four days, a phenomenal total for any book, let alone a sophisticated mock-heroic text whose concerns went well beyond the real-life scandal that had prompted its invention.

Curll saw his chance in a flash. One of the additions to the poem was a subplot involving sylphs, gnomes, and other fairy-like creatures who act as diminished equivalents of the gods in traditional epic, directing the actions of the heroine, Belinda. Pope’s source for this fanciful sideshow to the main amatory business was a largely flippant exposition of Rosicrucian ideas called Le Comte de Gabalis (1670) by a French priest, Nicolas de Montfaucon de Villars. He was long dead, found murdered on a roadside near Lyon (Voltaire suggested he was killed by the sylphs). His work consists of dialogues on hermetic philosophy cast in a light-hearted tone. One of Curll’s regular hacks, John Ozell—always a speedy man for such a task—had a translation ready by April 8, when it was jointly published by Lintot and Curll, billed as “a diverting history.” To enhance its otherwise limited sales potential, the volume was issued in a format “to bind up with the Rape of the Lock.”

Reprinted with permission from The Poet and the Publisher: The Case of Alexander Pope, Esq., of Twickenham Versus Edmund Curll, Bookseller in Grub Street by Pat Rogers, published by Reaktion Books Ltd. Copyright © 2021 by Pat Rogers. All rights reserved. Available from the University of Chicago Press.