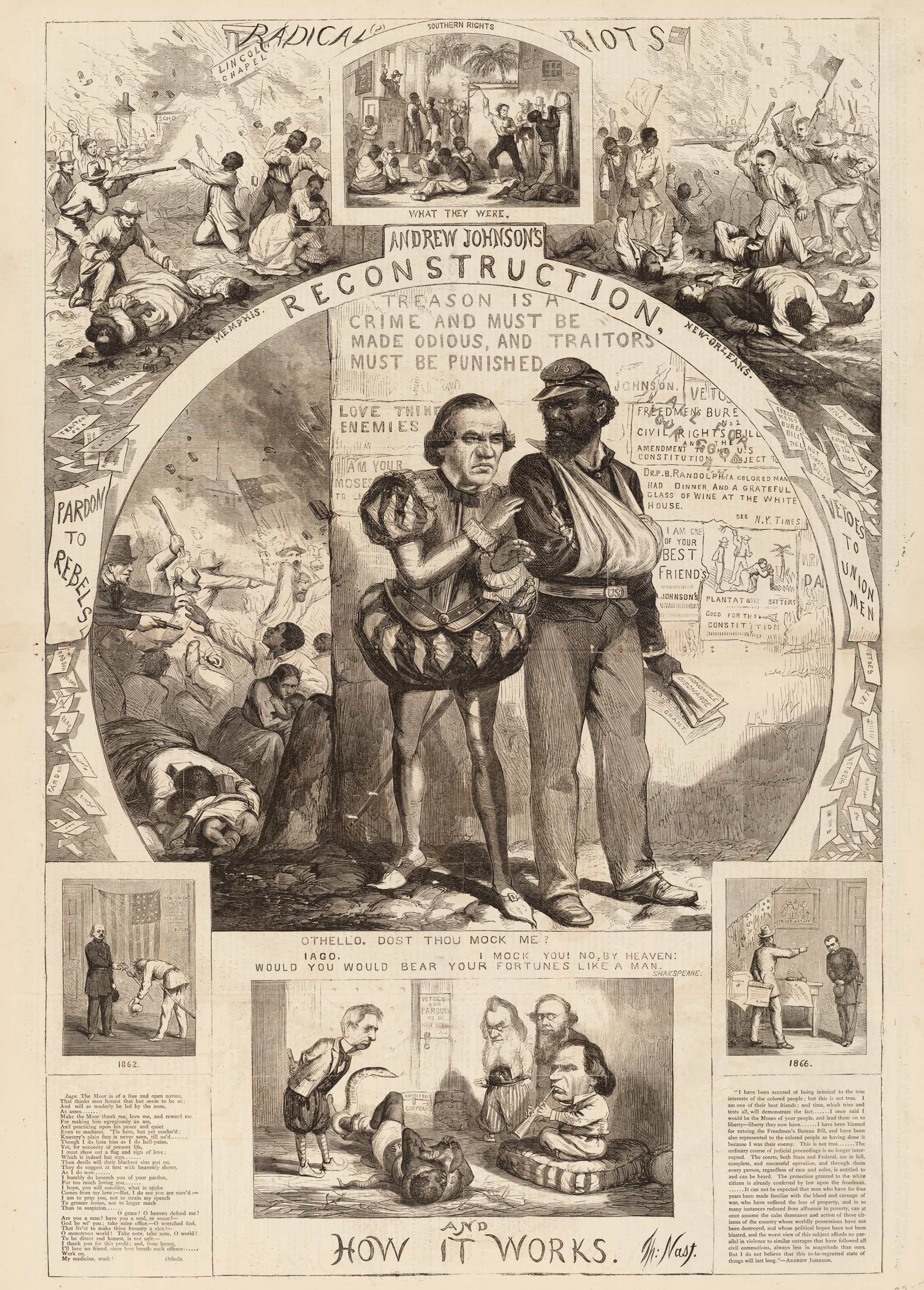

Andrew Johnson’s Reconstruction, by Thomas Nast, 1866. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution.

We complain of our Chief Executive of causing, by his agents, and Indulgence of Outlaws, much of the Outrages and Murders that have been committed on Loyal Subjects and Citizens of the Union in ten Rebel States since May 29, 1865.

We charge President Johnson, with giving aid and comfort to Outlaws…

We charge him with Usurping Legislative and Judicial power…

We charge him with wickedly, & boldly, striving to Reproduce Rebellion, by making Rebel Outlaws Governors, Judges, Sheriffs, Mayors, Clerks and the Police of the Ten Rebel States.

—“Petition of the Colored Free & Freed Citizens of Savannah, Georgia,” 1865

A document mixing humility with audacity, at once meticulous yet coursing with rage, the petition of Asa Cotton, James Hewett, Aaron Bradley, William Brown, Ishmael Palmer, and dozens of other men of color from Savannah arrived at the U.S. House of Representatives in the autumn of 1865. Walking their readers through a list of offenses, interspersing newspaper cuttings freely among their handwritten arguments to provide ready evidence for their claims, referring abundantly to constitutional clauses and to statutes, they laid out the case for President Andrew Johnson’s impeachment. The offenses alleged against Johnson by Savannah’s Black men were comparable in some sense, and yet far worse in other ways, to those launched by Thomas Jefferson at King George III in 1776. Having usurped powers not his, having failed to enforce laws passed by Congress, having aided an enemy (and in doing do plausibly committing treason), having encouraged a rebellion, having acted in ways murderous and wicked, Johnson deserved removal at minimum. The Savannah freedmen’s prayer reads as part memorial, part indictment list for a capital trial. It was possibly the first, and certainly the most radical, in a slew of petitions for Johnson’s impeachment that would arrive to Congress between 1865 and 1867.

The slaying of President Lincoln by John Wilkes Booth in April 1865 shook the continent. In Frederick Douglass’ timeless words, the murder established Lincoln as “the first martyr President of the United States.” Celebrated by southern whites, who saw an opportunity for newly reestablishing racial supremacy and even slavery itself, the event troubled and enraged freedmen and their abolitionist allies alike in the North. Andrew Johnson’s ascension to the American presidency was as accidental as the rise of any preceding executive.

Johnson’s behavior intertwined with white supremacist violence in the South, so much so that Black women and men, along with white abolitionists, rightly connected the two patterns. Johnson started provisionally readmitting southern states to the Union, acting on a theory that they had never truly left it (he could not, however, unilaterally admit them to representation in Congress). Harnessing Article II authorities in new and sweeping ways, he pardoned thousands of former Confederates in the summer and fall of 1865 (at a rate of approximately one hundred per day), quickly installing many of these men at the helm of reconstructed southern state governments. Pardoned and paroled Confederate soldiers, in turn, led the wave of violence on Black bodies and souls across the South. A former Treasury agent related the story of a pardoned former Confederate soldier who murdered a Black child, shooting him fifty-seven times. White southern men terrorized Black families, declaring them no longer free because Lincoln had died, attacking households and their property in ways wanton and systematic. Because Johnson’s actions were undertaken in the context of ongoing use of post-surrender war powers and because they undermined military occupation of the South, his presidency became especially odious to soldiers, veterans, and others well informed of the war effort.

The Savannah freedmen’s petition in the summer of 1865 conveyed precisely these kinds of stories, persuasively linking Johnson’s pardoning behavior with the wave of white-on-Black violence coursing through the South. The newspaper clippings attached to the petition relayed the “disgraceful scenes” of violence and required Confederate attestations that had unfolded at Norfolk municipal elections, the new daily reality of freedmen being “hunted down like dogs and dispatched without ceremony” wherever there were “no national troops,” and the “horrible condition of the freedmen in Alabama,” as a Boston Journal headline put it. To these newspaper reports the Black petitioners added other atrocities, primarily from Alabama, where Johnson’s “agents burn at will Negro houses and churches.” Those agents were Johnson’s responsibility under Article II, Section 4 of the Constitution. Beyond this, the unfolding list of brutalities was, in the petitioner’s charge, a willful violation of Black people’s Fourth Amendment rights. “They arrest and imprison at will men, women, and children…One hundred and thirty-three dead bodies were counted in the woods. Five bodies were seen floating in the water. Two white men were seen to pull a Negro down across a log, and cut his head off with an ax.”

Savannah was a logical font of Black organization and testimony. The city had become a center of Reconstruction Black community. Earlier that year, in January 1865, twenty of Savannah’s Black men, many of them Baptist and Methodist ministers in the city’s emerging independent churches, had met Union Army officers at General William Sherman’s request. The meeting resulted in a frank exchange of views that would come to be known as the “Savannah Colloquy.” The twenty congregants at Savannah espoused lucid conceptions of slavery and the freedom that they had won, and they reasoned strategically about how Black men free and enslaved could assist the Union effort. Some of the men who met with Sherman and Stanton appear on the Savannah impeachment petition’s signatory list, yet the autumn 1865 petition appears to have been led less by ministers than by veterans, including several who had fought in Massachusetts’ famed Fifty-Fourth Regiment, which had served in Savannah in March 1865, staying in Charleston and elsewhere in South Carolina for much of the summer (at least five of the signatories noted they were from Charleston). The drawing up of the petition coincides with the mustering and retirement of the Fifty-Fourth Regiment in August and September, and the regiment’s signatories—Asa Cotton, William H. Brown, Ishmael Palmer, Henry A. James, James C. Hewett, most from the Fifty-Fourth Regiment’s K Company—would have been in a good position to receive news of the atrocities and lawlessness throughout the South.

The radical nature of the Savannah freedmen’s petition lay not just in its text but in its targeted venue. For a half century or more, free people of color had rarely petitioned the U.S. Congress, especially when compared to the steady flow of their memorials to American state legislatures. Yet in 1865 the freedmen of Savannah launched their radical claim directly at Johnson and directly to the body that alone could impeach him. Ironically, Senator Charles Sumner’s response to the petition may have undermined the venue strategy of its Black signatories. Sumner’s aide Moorfield Storey reported that Senator Sumner himself received such a petition and took it directly to the president.

The assassination and Johnson’s early policies induced a renewed push for voting rights for Black men, and the petitioners who led this effort most vocally were Black men themselves—Black men from Washington, DC; Bern, North Carolina; Richmond, Virginia; Vicksburg, Mississippi; and Natchez, Tennessee. Directing many of their petitions directly to President Johnson himself, the early post-assassination memorials approached the new president with caution and respect. A petition displaying almost fifteen hundred names from South Carolina, men who said they “glory in the name of American citizens,” prayed Johnson to grant them the “protective rights of the elective franchise, which privilege we regard as the only means by which our class…will have the power of protecting ourselves and our interests against oppression and unjust legislation.” Whenever possible, Johnson redirected most of these petitions to the War Department, a pattern he did not repeat with white petitioners. Save for his curt dialogue with a delegation of Black ministers in June 1865, Johnson was generally unwilling to grant Black souls a hearing. He was, however, ready to tour his white constituencies in the North and South and deliver demagogic addresses with impromptu remarks insulting Black Americans.

The role of Black networks at the intersection of military and ministry resulted in other petitions in the fall of 1865, including the earnest appeals from Black farmers on South Carolina’s Edisto Island. Approaching Freedmen’s Bureau director Oliver O. Howard in October, in the midst of whites’ fresh appeal to reclaim the lands they had just lost in the rebellion, the Edisto petitioners announced their refusal to leave. “This is our home,” they intoned, reminding Howard, “We have made these lands what they are.” The Edisto petitioners employed the rhetoric and fact of “Loyalty”—Black petitioners systematically capitalized the word—to the Union cause, along with a Lockean logic of possession. Being “the only true and Loyal people that were found in possession of these lands,” they argued that their rights as “a free people and good citizens of these United States [are] to be considered before the rights of those who were found in rebellion against this good and just government.” Johnson countermanded General Howard’s Circular No. 13 that, had it been enforced, would have redistributed just short of a million acres of slave plantation land to free Blacks. In January 1866 he dismissed Brigadier General Rufus Saxton, the Union commander in charge of land distribution, putting an effective end to the project.

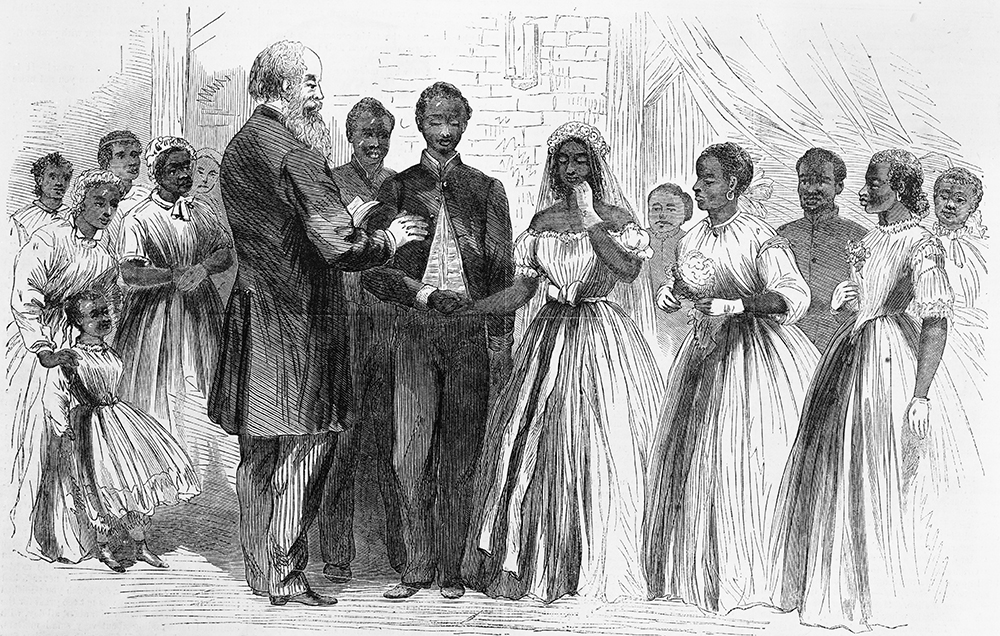

Black petitioners were busy contesting Johnson’s agenda elsewhere. The Freedmen’s Bureau established a petitioning system for grievances that lay somewhere between a judicial system, an administrative routine, and more traditional grievance petitioning. The bureau often set up offices in county courthouses or in the former properties of slaveholders whose assets had been confiscated by the Union. These places had conflicting meanings for Black petitioners. On the one hand, they were venues where freedwomen and freedmen could appear as citizen petitioners, with Black women having access to these spaces theoretically and symbolically equal to that of Black men. On the other hand, when freed Blacks brought their complaints to these places, they saw the sites of their recent bondage and they risked white aggression. In part for this reason, Freedmen’s Bureau visits often took the form of kinship-based petitioning collectives.

Johnson further enraged freedmen and their allies with his veto of the Freedmen’s Bureau bill in February 1866 and his veto of the civil rights bill the next month. Congress acted quickly to override these vetoes. Amid the struggle in Washington, white violence exploded in the South. White rioters massacred forty-six Black people in February 1866, while over one hundred African Americans perished in July riots in New Orleans. A perceptible swing toward Republicans in the autumn elections of 1866 (when the Republicans gained eight House seats while the Democrats lost a total of three, including three Pennsylvania districts surrendered to the Republicans) left the president facing his most radical legislative opposition yet.

Impeachment was not at the top of the Fortieth Congress’ agenda. Yet by the time the House had convened in March 1867, the previous Congress had, in its waning days, received and read thirty-eight petitions for Johnson’s impeachment into the record. Impeachment petitions came disproportionately from Illinois, Michigan, Ohio, and Wisconsin, as well as from the usual strongholds in Massachusetts, New York, and Pennsylvania. Two came from Georgia and one from Louisiana, two jurisdictions that still lay outside the Union but whose freedmen the Thirty-Ninth Congress recognized as petitioners; another came from the Black community in Paducah, Kentucky, and was read into the record in November. In the Senate, Charles Sumner read the “petition of colored citizens of the State of Georgia” first among impeachment petitions in his chamber’s record that calendar year; it asked for the protection of their “lives and property” and, in a radicalism that echoed that of the 1865 Savannah freedmen’s petition, called for payment of the war debt “from the proceeds of confiscated rebel property.” Eight times in January and February 1867 did Sumner introduce Black petitions to the Senate floor, not only from Massachusetts but also from Virginia and North Carolina. The only petitions read into the record against impeachment in the late Thirty-Ninth Congress came from New York, marked by two from the city and its “business men.”

The House presented the articles of impeachment to the Senate on March 4, 1868.

The freedmen of Savannah could believe that Johnson was impeachable, not only in the sense that sound legal grounds existed for a House indictment but also because national political institutions offered as never before a hearing for Black claimants. Those claimants could express not merely their humility but their fury and robust claims of vast lawlessness by the president. Impeachment would ensue, but conviction would not. It was only in 1868 that Republican voters, and not senators, removed Andrew Johnson from office.

Excerpt adapted from Democracy by Petition: Popular Politics in Transformation, 1790–1870 by Daniel Carpenter, published by Harvard University Press. Copyright © 2021 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College. Used by permission. All rights reserved.