The Yellow Room, by James McNeill Whistler, c. 1883. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Marguerite and Frank A. Cosgrove Jr. Fund, 2017.

On hot August nights in 1916, as war raged across the world, Aldous Huxley and Dora Carrington liked to abandon their stuffy attic bedrooms at Garsington, the Oxfordshire house where they were guests, to sleep on the roof. The twentysomethings whiled away the night talking and “singing folk songs and ragtime to the stars,” Huxley wrote to a friend. “Early in the morning we would be wakened by a gorgeous great peacock howling like a damned soul or woman wailing for her demon lover, while he stalked about the tiles showing off his plumage to the sunrise.” If you think this scenario belongs in a story, so did Huxley, who put it in his 1921 debut novel, Crome Yellow. Mary and Ivor, who are engaged in a flirtation, climb onto the roof to sleep “under the stars, under the gibbous moon.” At daybreak a “monstrous” peacock appears, emitting “the mournful scream of a soul in pain.”

Huxley drew much of that novel directly from the vie bohème at Garsington. At this seventeenth-century hillside manor, set in magnificent Italianate gardens, Lady Ottoline Morrell cultivated an artistic, intellectual, and sexual haven. Except a haven, of course, is marred by the curious gaze of an audience—a consequence to which Huxley paid no heed. Ottoline, shocked by his abdication of the novelist’s duty to make stuff up, denounced Crome Yellow as “simply photography, and poor ragged photography at that.”

Huxley was first invited to Garsington in 1915, when he was twenty-one, still at Oxford, and beginning to publish his poetry. The chance to make Ottoline’s acquaintance must have been intriguing, given her reputation as an impeccably well-connected salonnière. In a letter to his father, Leonard, Huxley characterized the striking, copper-haired forty-two-year-old as “a quite incredible creature—arty beyond the dreams of avarice and a patroness of literature and the modernities.” Descended from dukes and baronesses on both sides of her family, Ottoline had an open marriage with her husband, the Liberal politician Philip Morrell, and she gathered around her a rotating assortment of lovers, friends, and protégés. Virginia Woolf and her sister, the artist Vanessa Bell, were a familiar presence—the portraitist Augustus John had introduced Bell to Ottoline, his soon-to-be lover and sitter, in 1907—along with fellow members of the freethinking artistic clique known as the Bloomsbury Group. The young Huxley, six foot four inches tall, handsome, and aloofly charismatic, had no trouble gaining acceptance into this rarefied world. Juliette Baillot, governess and companion to the Morrells’ daughter, noticed he didn’t talk much on his first Garsington visit, “but as soon as he was gone, everyone agreed about the deep impression of unique quality, of gentleness and depth.”

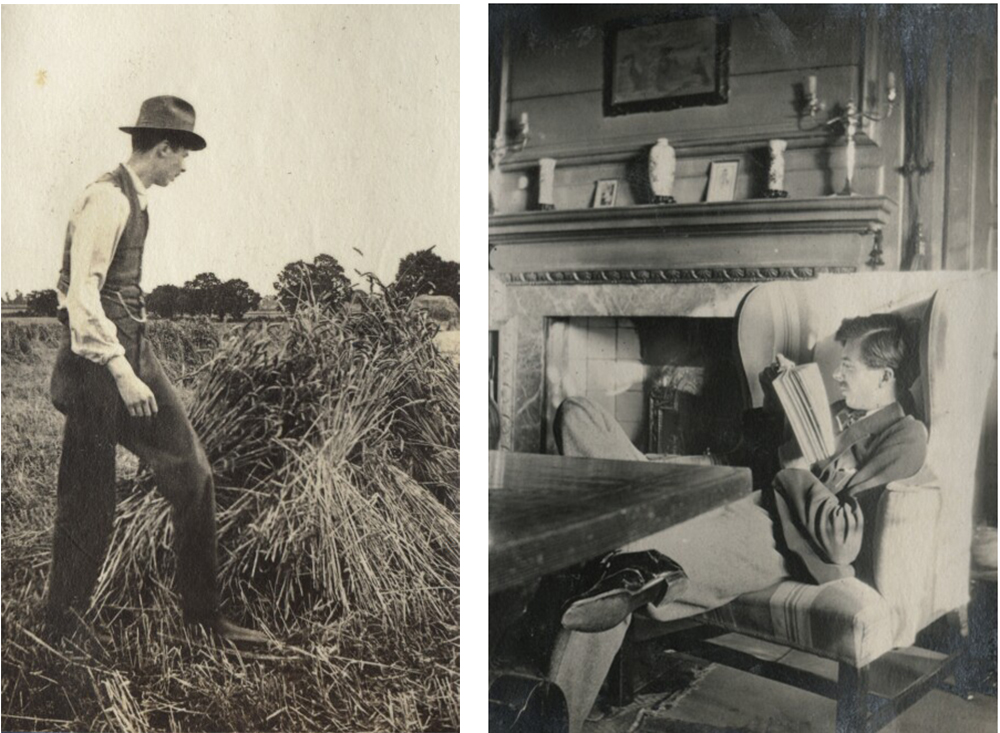

After Huxley graduated the following summer, he was kept from active military service by his bad eyesight, the legacy of a serious streptococcal eye infection at age sixteen. Instead he went to live and work at Garsington. On the estate’s two hundred acres of farmland, alongside conscientious objectors welcomed by the pacifist Morrells, he chopped trees for fuel (“hewing wood, like Caliban,” as he archly put it in a 1916 letter to Ottoline, who was away in the spa town of Harrogate). For the literarily ambitious Huxley, it’s hard to imagine a more desirable environment to be dropped into, wood hewing or not. As he reminisced in later life, it was there that he got to know “Virginia and Vanessa,” and other Bloomsbury types such as Clive Bell, Roger Fry, Bertrand Russell, John Maynard Keynes, and T.S. Eliot. “The meeting of all these people,” Huxley reflected in a 1961 Paris Review interview, “was of capital importance to me.”

Just as fatefully, at Garsington Huxley fell in love with a young Belgian named Maria Nys. With her mother, Marguerite, and three younger sisters, Maria had come to London to escape the German invasion of Belgium. Ottoline, who met the family through Marguerite’s brother Georges Baltus, an artist and professor at the Glasgow School of Art, invited Maria to stay at Garsington. The shy sixteen-year-old was infatuated with her hostess, once even attempting suicide in response to some perceived rejection. Slowly, she transferred her affections to Huxley, encouraged by the artist Dorothy Brett, who believed him in desperate need of looking after. Huxley’s own adolescence had been punctuated by tragedy: his beloved mother had died of cancer at forty-six and his brother Noel had died by suicide. Maria’s compassion was stirred, and after a long engagement the couple married in 1919. She was twenty, and he was about to turn twenty-five. (The same year, Huxley’s older brother Julian married Juliette Baillot. “You will think I keep a matrimonial agency,” Ottoline quipped to Leonard Huxley.) The Huxleys would frequently return to Garsington for weekend stays, until Crome Yellow caused their banishment.

Huxley was twenty-six, with several poetry collections and a book of short stories under his belt, when he decided it was high time he published a novel. To that end he left London, where he was obliged to toil at journalism to scrape together a living, and decamped to Italy with Maria and their baby son, Matthew. Over the summer of 1921, Huxley composed Crome Yellow in Forte di Marmi, a seaside town in northern Tuscany. It was the coast, he told The Paris Review, “where Shelley was washed up, under the mountains of Carrara, where the marble comes from. It was an incredibly beautiful place then.” He conceived Crome Yellow as a pithy entertainment in the tradition of Thomas Love Peacock, a friend of Shelley’s who wrote popular satirical novellas, often set in country houses. “I lack the courage and the patience,” Huxley confessed to H.L. Mencken, “to sit down and turn out eighty thousand words of Realismus. Life seems too short for that.”

In drawing firsthand inspiration from, in Henry James’ words, “the gilded bondage of the country house,” Huxley was far from alone. James himself, a habitué of weekend parties at grand family seats, liberally appropriated those settings for his fiction. Life at Knole, Vita Sackville-West’s vast childhood home in Kent, is portrayed mischievously in her best-selling 1930 novel The Edwardians. (Weekend-party bed-hopping was aided by, the reader learns, “the name of each guest…neatly written on a card slipped into a tiny brass frame on the bedroom door.”) Knole is a main character in Woolf’s Orlando, whose eponymous protagonist is clearly her lover Sackville-West. Bloomsbury authors were frequently fictionalizing one another. In writing Howards End, E.M. Forster modeled the culturally sophisticated Schlegel siblings on Vanessa, Virginia, and Thoby Stephen. Mark Gertler, the Jewish painter championed by Ottoline, saw his tormented relationship with Carrington dramatized in Gilbert Cannan’s 1916 novel Mendel (in which Ottoline also makes a cameo). Gertler, outraged, called the book “a piece of cheap trash.” Nevertheless, coverage from critics and gossip columnists ensured its success, inspiring Brett to buy “a darling tab book to write my Garsington memoirs in!!”

Huxley’s own Garsington novel was published by Chatto & Windus in November 1921, followed in March 1922 by a U.S. edition from George H. Doran. On both sides of the Atlantic, Crome Yellow’s critical reception was very warm indeed. “This is the highest point so far attained by Anglo-Saxon sophistication,” F. Scott Fitzgerald wrote in the St. Paul Daily News. (Many years later, after both novelists had gone to Hollywood, Fitzgerald put Huxley in The Last Tycoon as George Boxley, a British writer whose literary sophistication seems ill-suited to “making pictures.”) The reviewer for the Times Literary Supplement enthused that “Mr. Huxley’s personages are drawn with an extreme verve of crispness; in fact the merit of his comedy is that it becomes always more amusing as it grows.” Though Huxley wrote eleven more novels, most famously the dystopian masterpiece Brave New World, and published many short-story and essay collections, Crome Yellow is widely regarded as his most lightheartedly enjoyable work.

The title, a homophonic play on the popular nineteenth-century paint pigment chrome yellow, describes the setting: Crome, a grand country house in “the green heart of England,” bathed in the golden haze of a late summer sun. At this aristocratic idyll, a weekend party is being hosted by Crome’s astrology-mad, gambling-addicted chatelaine, Priscilla Wimbush, and her husband, Henry, the author of History of Crome. Finally complete after decades of work, this ancestral record is largely placid and uneventful, Henry reports. “I can only think of two suicides, one violent death, four or perhaps five broken hearts, and half a dozen little blots on the scutcheon in the way of misalliances, seductions, natural children, and the like.”

Various guests at the Wimbushes’ party are recognizably based on figures from Garsington, none more so than Carrington as Mary Bracegirdle. Before proposing to Maria, Huxley had been in love with Carrington, but she, observed Ottoline, “had many admirers, and fluttered from one to another.” She planned to abstain from sex, much to Huxley’s perplexity. “Carrington and I had a long argument on the fruitful subject of virginity,” he wrote in a 1918 letter to Brett. “I may say it was she who provoked it by saying that she intended to remain a vestal for the rest of her life. All expostulations on my part were in vain.” And so Bracegirdle’s defining characteristic, along with Carrington’s “bell of elastic gold” hair and “large blue china eyes,” is a preoccupation with her virginity, signaled by her Dickensian aptronym.

Mary’s caddish love interest, Ivor Lombard, was in turn based on Evan Morgan, an aristocratic Welsh poet. Mr. Scogan, an opinionated middle-aged philosopher, is a thinly disguised Bertrand Russell, Ottoline’s longtime lover. Jenny Mullion, a young deaf woman with preternatural intuition, is a rather admiring portrait of Brett. Gombauld, a Byronically handsome French artist, is obviously Gertler. Anne Wimbush, the hosts’ pretty niece, seems to be the writer Mary Hutchinson, Lytton Strachey’s cousin and eventual lover of both Huxley and Maria. Our author proxy is Denis Stone, the young poet-protagonist whose sentimental disenchantment, as he tries to woo Anne, is what passes for a plotline through a series of witty set pieces and farcical misunderstandings. Just as chrome-yellow paint darkens when exposed to light, the mutual obscurity of these characters’ true selves only deepens as they try to connect. “Did one ever establish contact with anyone?” Denis wonders. “We are all parallel straight lines.”

If most of Huxley’s readers couldn’t have known who, exactly, inspired his characters, his general lampooning of the upper classes played into the disillusioned postwar zeitgeist, as would The Great Gatsby a few years later. And in Crome Yellow’s conversations and inner ruminations we perceive not only the personalities and preoccupations of real people but also the gathering revolution in social and sexual mores. With shades of Brave New World, Mr. Scogan proclaims that eventually “vast state incubators” will replace “Nature’s hideous system,” allowing Eros “to flit like a gay butterfly from flower to flower through a sunlit world.” Mary, a reader of Freud and Havelock Ellis, worries that repressing her sexual impulses will lead to nymphomania, and so she assesses the evolutionary fitness of the available men. Henry, feeling that the joys of human contact are overrated, looks forward to the “perfectibility of machinery,” when it will be possible “to live in a dignified seclusion, surrounded by the delicate attentions of silent and graceful machines.”

These musings are interspersed by Henry’s comical recounting of key episodes from his History. The alluringly ethereal Lapith sisters, for instance, were residents of Crome who publicly refused all but the tiniest morsels of food. “Pray, don’t talk to me of eating,” Emmeline said. “We find it so coarse, so unspiritual, my sisters and I. One can’t think of one’s soul while one is eating.” The story of the Lapiths, told over ten or so pages, is an out-of-the-gate flexing of Huxley’s gift for timelessly resonant satire, another element that elevates the novel above a straightforward roman à clef. In Barbara Pym’s Excellent Women, published thirty years later, the beautiful (and not so excellent) Allegra Gray pushes her food around her plate and admits, “I’m like the young ladies in Crome Yellow. Although it isn’t so easy nowadays to go home and eat a huge meal secretly.” In 2005 the food critic Fay Maschler was reminded of the Lapith sisters by the “itty-bitty dishes served to wraithlike young women” in a chic Notting Hill restaurant.

Pym credited her awakening as a novelist, at age sixteen, to Crome Yellow. In a 1978 talk she gave on BBC Radio titled “Finding a Voice,” she said:

I came across this sophisticated masterpiece in the wilds of Shropshire, through that marvelous institution Boots’ Library…I was a keen reader of all kinds of modern fiction, and more than anything else I read at that time Crome Yellow made me want to be a novelist myself. I don’t suppose for a moment that I appreciated the book’s finer satirical points, but it seemed to me funnier than anything I had read before, and the idea of writing about a group of people in a certain situation—in this case upper-class intellectuals in a country house—immediately attracted me, so I decided that I wanted to write a novel like Crome Yellow.

Those who saw themselves in Crome Yellow were understandably less delighted by it. Carrington described it as “a book which makes one feel very very ill.” Decades later, Russell was still annoyed that ideas postulated seriously by Mr. Scogan were ones he’d offered jokingly among friends. But most of all it was Ottoline whose feelings were hurt; after everything she’d done for Huxley, this was how he repaid her. “When I read in it the description of life at Garsington,” she wrote in her memoirs, “all distorted, caricatured, and mocked at, I was horrified.” She had already been devastated when D.H. Lawrence, a close friend, parodied her as Hermione Roddice in Women in Love, a character described as “macabre” and “repulsive.” With Crome Yellow, her biographer Miranda Seymour writes, “Ottoline cared a good deal less about any faint resemblance Priscilla and Henry Wimbush might bear to herself and Philip than the fact that the novel was crowded with caricatures of her friends and wartime guests.” It would be years before she forgave him. She blamed Maria, too, as an alleged enabler of her husband’s crimes.

Huxley, who insisted he had caricatured only himself in Denis, was genuinely distraught that “a marionette show…a comedy of puppets” could destroy a cherished friendship. (Woolf, after comforting a still-reeling Ottoline months later, recorded ruefully in her diary, “But mere marionettes have destroyed it.”) At the same time, he found it irritating that his acquaintances were so eager to identify the originals of his fictional cast. He viewed his creativity as a process more recondite than simple mimicry, as most novelists do, and he refused to acknowledge he’d done anything wrong. “I am not a realist,” he stated, “and don’t take much interest in the problem of portraying real living people.” Another literary pilferer of high society, Truman Capote, had a different attitude, breezily remarking of Answered Prayers, his notorious unfinished novel, “Almost everything in it is true.” His characters, he assumed, would be “too dumb” to recognize themselves. He was mistaken. “Never have you heard such gnashing of teeth,” gossip columnist Liz Smith wrote in New York after chapters were published in Esquire, “such cries for revenge, such shouts of betrayal and screams of outrage.” Capote was shunned by his blue-blooded “swans,” which hastened his descent into the addiction that led to his ultimate demise.

Ottoline’s anger aside, Huxley suffered no such fallout and continued mixing with the Bloomsberries et al. Nor was he remotely deterred from mining his social circle for fiction. A version of Ottoline again appeared in 1925’s Those Barren Leaves, while 1928’s Point Counter Point featured sketches of D.H. and Frieda Lawrence, the heiress Nancy Cunard (with whom Huxley had a brief but on his part obsessive affair), Brett, and Katherine Mansfield’s husband John Middleton Murry. It was, after all, the world Huxley knew best: writers, artists, and the socialites who collected them. “I have never so much as passed a night in any of the great industrial towns of the North,” he had confessed in a 1920 essay. “I have never talked to a miner or a steelworker or a cotton operative.” Moreover—not yet having bit the hand that fed him—he was glad of the aristocratic largesse bestowed on such “savages of the mind” as himself, predicting that soon “the advancing armies of democracy will sweep across their borders and these happy sanctuaries will be no more.”

He was right. Garsington, like many country houses of the era, became too expensive to run and was sold in 1928. “Sometimes I felt as if Garsington was a theater,” a pensive Ottoline later recalled, “where week after week a traveling company would arrive and play their parts…How much they felt and saw of the beauty of the setting I never knew.” Today Crome Yellow endures as a sparkling snapshot of that theater, a visionary novelist’s precocious debut, and an exemplary lesson (to writers and their unfortunate friends) in Nora Ephron’s maxim “Everything is copy.” As Henry Wimbush reflects while reluctantly hosting a fete:

Adventures and romance only take on their adventurous and romantic qualities at secondhand. Live them, and they are just a slice of life like the rest. In literature they become as charming as this dismal ball would be if we were celebrating its tercentenary. Ah, if only we were!