Kirtlington Park, Oxfordshire: View of the Dining Room, by Susan Alice Dashwood, 1876. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Edward Pearce Casey Fund, 1993.

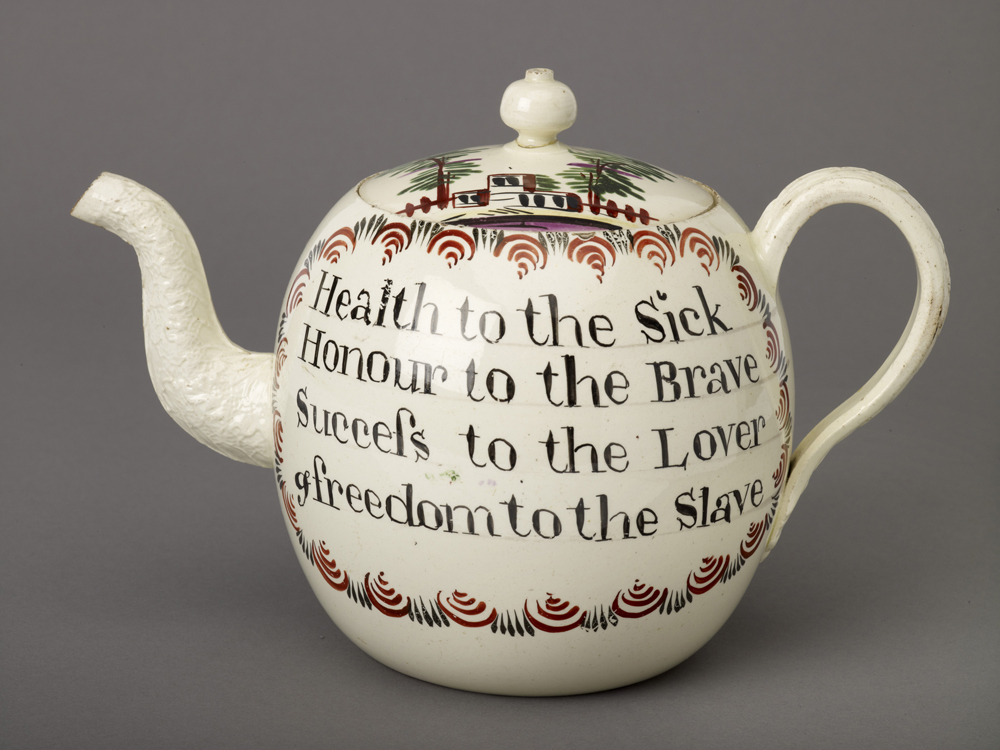

Around 1760 Josiah Wedgwood’s pottery factory in Staffordshire, England, began manufacturing teapots with an interesting bit of verse on them:

Health to the sick

Honor to the brave

Success to the lover

And freedom to the slave

The lines are attributed to the English poet Richard Duke from his 1717 poem “The Review.” It’s not clear whether or not Duke himself was particularly sympathetic to the atrocities faced by enslaved women and men, but the teapot decorated with his verse was designed to signal support for antislavery sentiments. By 1791, when pamphleteer William Fox called on his fellow citizens to abandon “blood sugar” in his “Address to the People of Great Britain, on the Propriety of Abstaining from West India Sugar and Rum,” teapots like this one were part of the campaign.

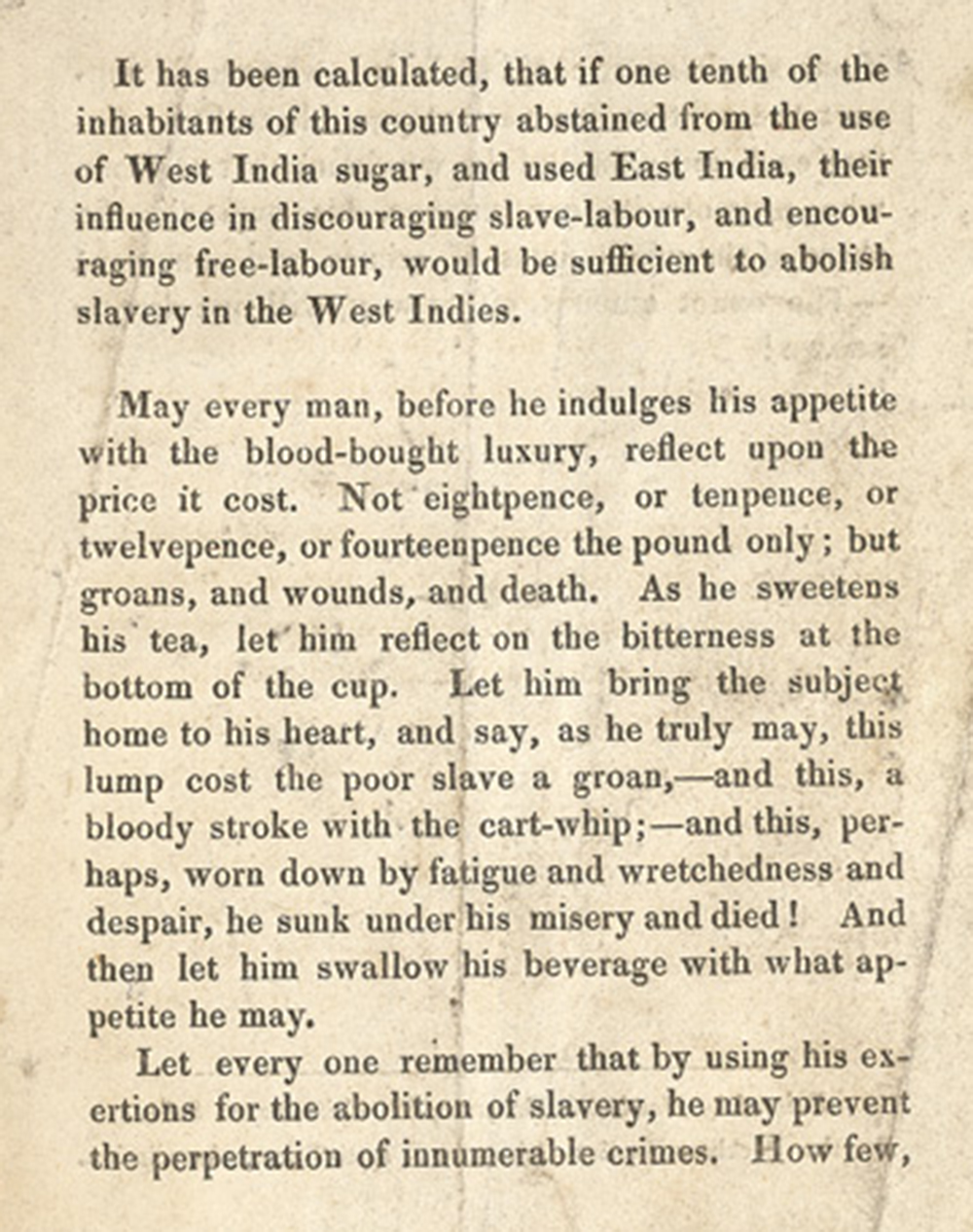

The tea table that we now associate with quaint rituals, scones, crustless sandwiches, and charming desserts served on porcelain with sterling silver cutlery was a more political space in the eighteenth century, and antislavery conversations played a big part of the politics of the time. Fox and others targeted sugar in part because of its ubiquity in English households. By the 1790s what had once been a delicacy enjoyed by the wealthy and elite for celebrations was now a regular part of the English diet. The antislavery activists made explicit the connection between the inhuman trade and those who benefited from it. “If we purchase the commodity,” Fox wrote, “we participate in the crime. The slave dealer, the slave holder, and the slave driver, are virtually agents of the consumer, and may be considered as employed and hired by him to procure the commodity.”

These teapots offer us interesting insights into England’s political culture in the eighteenth century, telling a story of how the British wrestled with their reliance on the transatlantic slave trade and how white women, many of whom saw in the movement a way to place themselves in the middle of national debates, were more central to the debate than we might otherwise think. For critics and scholars interested in this moment—both its philanthropic sheen and its self-serving undercurrents—these teapots reveal the complexity of one of the first political causes British women publicly embraced.

Historian Clare Midgley notes that the same year Fox’s pamphlet was published, a comment in the Chester Chronicle put the success of the abolition campaign on the shoulders of women: “City meetings might make resolutions upon resolutions to little purpose…unless we first gain over wives and daughters.” And in 1795 an irritated Samuel Taylor Coleridge—he of the chatty mariner—announced that if women were as sensitive and full of feeling as they claimed, they would give up sugar drenched in the blood of their brethren. While this concern had something to do with caring for the victims of the slave trade, it also had a lot to do with a domestic tug-of-war between British women and men.

Women’s buying power increased over the course of the eighteenth century, and buying expensive and fragile china was particularly appealing. Cultural historian Karen Harvey points out that this habit was derided by Joseph Addison, essayist, playwright, and cofounder of the daily satirical magazine The Spectator. Frustrated that women were spending money on a commodity so easily shattered by servants, he wryly notes:

The common way of purchasing such trifles, if I may believe my female informers, is by exchanging old suits of cloaths for this brittle ware…I have known an old petticoat metamorphosed into a punch-bowl, and a pair of breeches into a tea-pot…in reality this is but a more dexterous way of picking the husband’s pocket, who is often purchasing a great vase of china, when he fancies that he is buying a fine head, or a silk gown for his wife.

On top of this taste for china, consuming sugar was seen as a threat to everyone’s health but especially women, who were thought to have a palate more sensitive to sweet substances. These same women not only saw their own plight in that of the enslaved but also were eager to prove that their moral influence and political acumen deserved a place in national politics. It’s no accident that, by feminist literary critic Moira Ferguson’s count, Mary Wollstonecraft used some version of the word slave eighty times in A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, while it appeared only about four times in her Vindication of the Rights of Man. Tired of being seen primarily as frivolous creatures who would leave their husbands shirtless to set a fashionable table and waste their emotions on useless luxuries if left to their own devices, British women found in the antislavery movement a perfect way to perform empathy, philanthropy, and, most notably, gravitas. And they could do it while still being fashionable.

When Fox called for the consumer boycott, women embraced the cause fully—in pamphlets, poems, and fiction and at their tea parties. They collected signatures for antislavery petitions, formed antislavery societies, and the Sheffield Female Anti-Slavery Society circulated cards that showed the “math” of blood sugar: “By six families using East India instead of West India Sugar one Slave less is required…The labour of one Slave produces about Ten [hundred weight] of Sugar annually.” A person identified as “Humanus” wrote to the Newcastle Courant a year after Fox’s pamphlet was published to report, “Happening lately to be sometime from home, the females in my family had in my absence perused [Fox’s pamphlet]…On my return, I was surprised to find that they had entirely left off the use of Sugar, and banished it from the tea table.”

Enter the abolitionist teapot and all that went along with it: pitchers, bowls, cups, and saucers. Buying teapots with a moral cause mitigated some of the critique of women as natural spendthrifts. A man still might lose his shirt so his wife could buy a teapot—but at least it was for a good cause.

It’s not clear how many abolitionist teapots were manufactured, but between 1760 and 1865 you could find them in England, France, and the United States. Some were cheaply made, suggesting they were designed for mass production, while others were hand-painted and intended for special occasions. Some were made of creamware, others porcelain. They could be decorated with the lines from Duke’s poem. Others featured a black female figure on one knee, in the same position as the black male figure on Wedgwood’s antislavery medallion, which had the words “Am I not a man and a brother?” engraved over the man’s head. In addition to Wedgwood’s own strong antislavery sentiments, his friendship with leading abolitionist Thomas Clarkson put him at the center of a community of businessmen and civic leaders committed to dismantling transatlantic slavery. Designed specifically for the Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade, the medallion, a little smaller than an American quarter, was used to raise awareness in England and the United States. It was adapted into jewelry for men and women alike, with women putting the image on hairpins and bracelets. It’s easy to imagine a hostess wearing her Wedgwood medallion jewelry as she sat down and served tea from her abolitionist tea service.

The campaign got under the skin of proslavery advocates. In a letter to a local newspaper, one such person wrote, “In this neighborhood we have antislavery clubs, and antislavery needy parties and antislavery tea parties and antislavery in so many shapes and ways that even if your enemies do not in the end destroy you by assault, those who side with you must give you up for the weariness of the subject and resentment of your supineness.” It’s unclear if the letter’s author recognized that part of the verse used on the teapots (“success to the lover”) was appropriated from proslavery punch bowls manufactured between 1760 and 1806 and decorated with slave-trading ships. As archaeologist Jane Webster notes, the bowls heralded specific vessels, with phrases such as “Success to the Dobson” or—rather bizarrely, given its purpose—“Success to the Friendship.”

Boycotting sugar didn’t end the slave trade. That wouldn’t happen until 1807, and it took until 1833 to end slavery in England. Even then, the Slavery Abolition Act stipulated that the enslaved remained bound for five to seven additional years. But by 1795, according to Maria Edgeworth, author of the short story “The Grateful Negro,” some 400,000 British people had given up so-called blood sugar. The moral quandaries it brought to the fore didn’t disappear. In 1826 novelist Amelia Opie published a poem for children titled “The Black Man’s Lament, or, How to Make Sugar.” Written to inspire abolitionist sentiment in the young (“Oh try to end the grief”), the illustrated poem is unvarnished in its condemnation:

There is a beauteous plant, that grows

In western India’s sultry clime,

Which makes, alas! the Black man’s woes,

And also makes the White man’s crime.

In more commercial corners, Suffolk merchant James Wright felt comfortable enough with the campaign to declare in the local paper that he would stop selling tainted sugar:

Being impressed with a sense of the unparalleled suffering of our fellow creatures, the African slaves in the West India Islands…with an apprehension, that while I am dealer in that article, which appears to be principal support of the slave trade, I am encouraging slavery, I take this method of informing my customer that I mean to discontinue selling the article of sugar when I have disposed of the stock I have on hand, till I can procure it through channels less contaminated, more unconnected with slavery, less polluted with human blood.

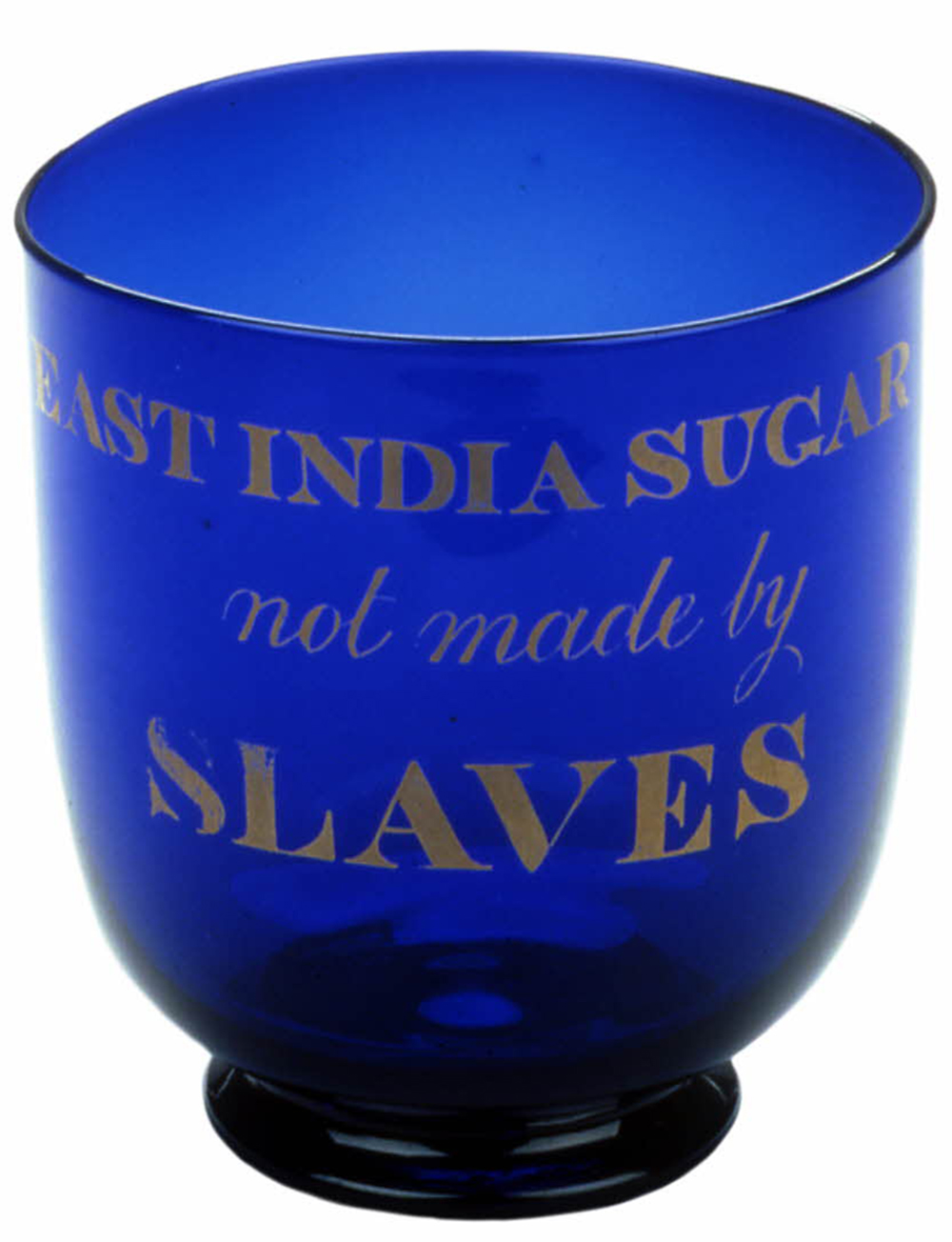

Another tea object reflects the movement’s influences.

A sugar bowl announces its politics simply: “EAST INDIA SUGAR not made by SLAVES.” Other sugar bowls from around 1820 are inscribed similarly: “The Produce of Free Labor,” for example. Replacing “blood sugar” with “East India” sugar posed its own moral quagmire, of course, and reveals the limits of abolitionists’ empathy and British law. “East India” sugar was also the product of slavery, a fact that didn’t seem to trouble abolitionists as much, in part because the conditions of the enslaved in the East Indies weren’t as widely known. Instead the term indentured servant was broadly used to describe a system that was in fact enslavement. More significantly, the fortunes of some abolitionists were closely tied to commerce in the East Indies, so they had a financial interest in making East India sugar a socially acceptable replacement for the West Indian product. Slaveholding wouldn’t be banned there until 1862.

Today you’ll find these teapots illustrating informative blog posts about abolition, in private collections, on Pinterest, and in museums. A tête-à-tête tea set currently on display in the Brooklyn Museum shows how images that were once used to inspire sympathy changed after crossing the Atlantic. If the original British pots featured images of enslaved women and men on them, the American versions turn subjects of sympathy into objects of caricature. In the 1860s Union Porcelain Works in Greenpoint, Brooklyn, manufactured the Brooklyn Museum’s tea set, which pointed, quite literally, to the origins of the products it would have contained. Most benignly, the handle on the creamer is in the shape of a goat to indicate that the milk comes from goats. Less so, the finial on the sugar bowl is a black man’s head to make clear his connection to sugar production, and, for similar reasons, the finial on the teapot is a Chinese man’s head. A curator’s note tries to explain that while we might see this as racist (because it is), in its own time it would have been seen as humorous.

This is only partly true. Every age has those who find offensive caricatures funny, but in at least one novel of the time, enjoying this kind of design is taken as a sign of moral weakness, if not outright racism. The Scottish novelist Susan Ferrier offered a cautionary tale about a frivolous, empty-headed young woman named Lady Juliana in her 1818 novel Marriage. Ferrier, an antislavery advocate, describes Lady Juliana as a terrible mother with “perverted taste.” One way we know her character is lacking is because she wants to buy an expensive teapot shaped like a Chinese man in a begging position, designed in such a way that water pours out of his mouth when tipped over to serve its contents. It’s a grotesque, offensive object, and the morally upright figures in the novel know it. As she coos delightedly over it, her husband looks on in horror. Despite Ferrier’s abolitionist sympathies, in this instance, the teapot is not meant to signal antislavery sentiments; rather, it suggests that bad taste and bad behavior are intertwined. It’s a critique that rings with more force once we understand the teapot culture it refers to—not imaginary sets, but real ones manufactured for British women and the campaign they embraced.