Statue, Mesopotamia, c. 2400 bc. © The Trustees of the British Museum (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0).

As high priestess of the Moon God in the Sumerian city of Ur around 2300 bc, Enheduanna was part of a long lineage of officials who looked to the night sky for divine guidance. Priests in the nearby city of Uruk, where writing was invented a millennium earlier, were likely the first to divide a year into twelve lunar months. The first sighting of a slender crescent on the western horizon inaugurated the beginning of a month, and its disappearance marked the end.

Ur was one of a few dozen Sumerian-speaking cities on the southernmost tip of the Fertile Crescent in what is today southern Iraq. These were the world’s first cities, constructed with such majesty that the earliest creation myths suggest the original Eden wasn’t a garden—it was a Sumerian city, meant to settle the gods in “the dwelling of their hearts’ delight.” Lunar calendars helped temple officials administer these cities: with consistent timekeeping came steady food rations, orderly archives, and well-timed cultic festivals. For the farmers, the rising of certain stars marked the beginning of the harvest, when they plowed the fields of barley and sent baskets of grain to the temple storehouses.

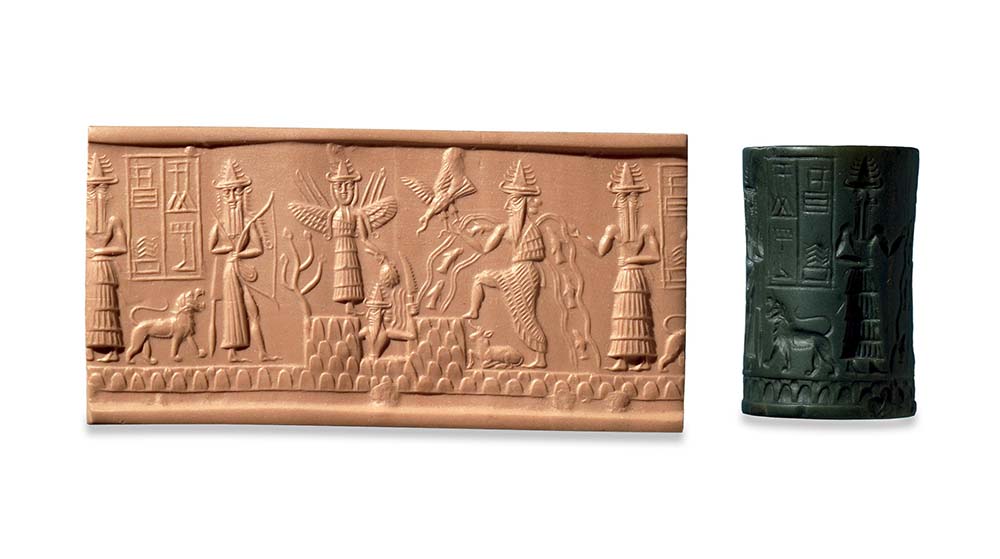

But Enheduanna didn’t just observe the sky to determine when to inaugurate a new month. The hymns she sang from the temple summit weren’t the same anonymous devotional songs performed for generations. She is the world’s earliest-known author and the first person to make herself visible in a work of literature. “I am Enheduanna,” she inscribed in the middle of two hymns. “I am still the splendid high priestess!” For the first time in history, a writer used poetry not just to praise the gods but also to share details from her own life. In a handful of autobiographical verses, she recounts being thrown out of the Moon God’s temple by a pretender to the throne. “I fled like a swallow swooping through a window,” she writes. “He took the crown of the high priestess from me.” The goddess Inanna, rebel daughter of the Moon God, ultimately saves her. “Lovely lady of heaven,” she calls her. “A queen astride a lion.”

Beyond this moment of crisis, only a few things are known about Enheduanna. She was the daughter of the Akkadian king Sargon the Great, who founded history’s first empire, the Akkadian empire. By 2334 bc, Sargon had traveled from his northern capital Agade with more than five thousand troops, conquered the Sumerian cities, smashed their towering brick walls, and appointed Enheduanna at the helm of the Moon God’s temple in Ur. In an inscription that accompanies Enheduanna’s only surviving portrait—a moon-shaped relief inscribed in alabaster held at the Penn Museum in Philadelphia—she identifies herself as the Hen of the Moon God, a title that refers to her ritual role as the Moon God’s wife. Other than presiding over lunar rites, the specifics of this position are largely unknown. Several historians argue Enheduanna was the most famous woman of her time, while others claim she hardly mattered. Some assume her portrait, with its noble hooked nose, represents what she looked like, while others insist it has nothing to do with her physical appearance.

The historian Marc Van de Mieroop describes the field of ancient Near Eastern history as “a dark room with isolated points of light, some brighter than others, provided by the sources,” and the same thing is true about Enheduanna. The most important sources for understanding her life and legacy are her dozens of surviving poems, which interweave local religious traditions across her father’s empire into a cohesive theology and proclaim the goddess Inanna to be the most powerful deity in the pantheon. Inanna was the personified form of the planet Venus, which at the time was still known as the morning star and evening star, likely because the planet was visible just before dawn and after dusk. “Good woman, inscrutable and radiant,” Enheduanna writes. “Your rule extends from zenith to horizon.” Her poems are the earliest known texts about Inanna, and she appears to ground the deity’s signature duality—“to destroy and to create, to plant and to pluck out are yours, Inanna”—in her celestial properties, the way Venus always hovers on a threshold. Enheduanna also emphasizes Inanna’s unpredictability—“nobody can know her course”—a characteristic perhaps informed by the way the morning star and evening star disappear for months at a time, blotted out by the sun and moon.

What is clear, if little else is clear about Enheduanna’s life, is that when she flung back her neck to observe the heavens, she was searching for Inanna. Enheduanna’s longest and most well-known hymns tell the story of how the goddess, “born to be a second-rate ruler,” rose to become even more powerful than her father, the Moon. It’s tempting to imagine she was also hoping to see herself reflected in Inanna’s unlikely ascendence. While the moon is the brightest force in the night sky, Enheduanna’s father Sargon the Great was the most powerful man on earth—“King of the World,” he claimed in his royal inscriptions. Enheduanna herself became one of the most canonical poets of Mesopotamia, her work copied by scribes across the region for nearly a millennium.

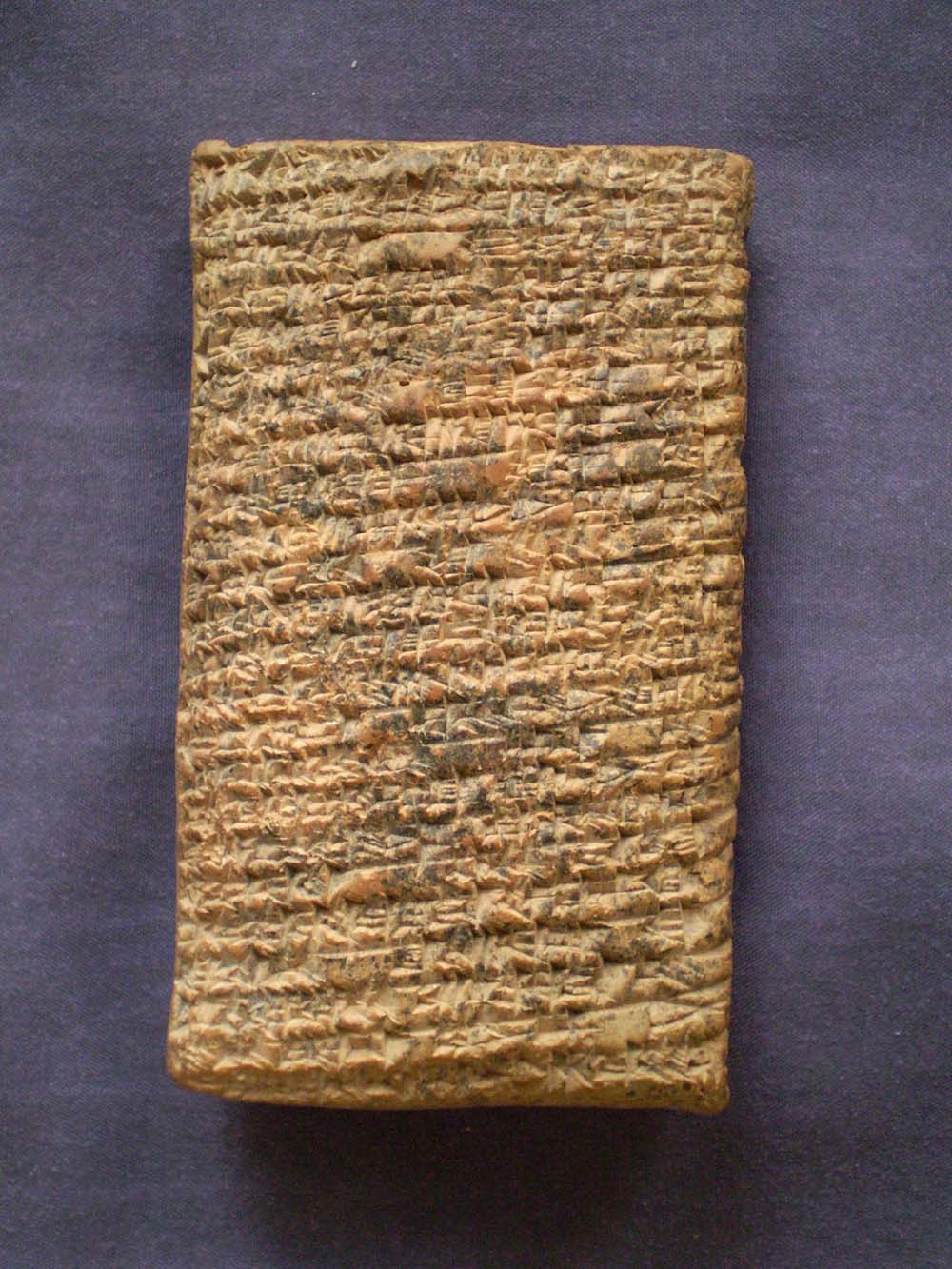

Historians date the earliest astronomical texts to over six centuries after Enheduanna’s death, to the reign of a Babylonian king named Ammisaduqa. As historian Francesca Rochberg argues in her 2004 book Heavenly Writing, the systematic study of celestial phenomena arose “in a context of state-sponsored divination,” where happenings in the heavens were viewed as “portents” for kings. Employed by Ammisaduqa, the first known astronomers tracked the appearance of Venus every night for twenty-one years, and devised omens meant to guide the king’s military, diplomatic, and economic decisions. Here is an example of one of their omens, which were always posed as conditional statements: “If on the fifteenth of Month XI Venus disappeared in the west, remained invisible three days, and reappeared in the east on the eighteenth day of Month XI, then catastrophes of kings. Adad will bring rains, Ea will bring floods, one king will send greetings to another king.”

Historians of the period have argued that these astronomical practices, where patterns in the sky were used to predict events on earth, evolved from earlier Sumerian traditions whose records were either lost or never written down. Enheduanna’s poems are not nearly as detailed as these later omens, but her verses similarly reflect an attempt to capture the night sky and make sense of its inscrutable forms. Just as the later astronomers tracked Venus, Enheduanna tries to capture Inanna’s astral manifestation, admiring the way she “brings beauty to the firmament at dusk.”

If the first astronomers tracked patterns in the sky to predict events on earth, Enheduanna seems more interested in drawing parallels between heaven and earth. Her celestial imagery casts the unknowable realm of the sky into a familiar terrain, populated by charming images. She describes the Moon as the one who “steps forth on the night sky that glitters like lapis lazuli,” evoking the idea, echoed in later poetry, that the sky was a giant lapis lazuli tablet, its constellations like the flecks of gold on that valuable stone. She also compares the moon’s crescent to the crown of the region’s most sacred animal: “You raise your horns as if you were a bull.” The sun’s light is like facial hair, sweeping over the land: “In the soaring daylight, a beard hangs from his chin.”

As the Assyriologist Thorkild Jacobsen argues in his 1978 book Treasures of Darkness, figurative language is the means by which experiences of the divine are communicated, and “religious content and forms are handed down from one generation to the next.” Enheduanna’s poetry reverberates across the written tradition, likely influencing texts that informed the Old Testament—and yet almost nothing has been written about her possible contributions to the field of astronomy. Many of Enheduanna’s images are echoed in later celestial records, suggesting that her verses could have informed how astronomers conceived of the heavens. The Sun God’s beard became a way to express the brightness of planets; the “beard” of Venus was often invoked to capture its overwhelming gleam. The logic of celestial omens—if X in heaven, then Y on earth—relies on a basic sense of parallelism: heaven and earth are cast as interconnected realms, much as they appear in Enheduanna’s verses. In addition, the historical chronology makes it appear almost certain that early astronomers would have read Enheduanna’s work. Babylonian diviners were trained as scribes, and Enheduanna’s poems were part of their standard curriculum, called the Decad, which also included an early story about the hero Gilgamesh.

Given how little we know about Enheduanna’s life, and how challenging it is to trace her influence with any precision across vast periods of time, her celestial images also function as historical constants, connecting Enheduanna not just to these later astronomers, but also to today. It’s possible to understand firsthand how the crescent moon does look like a pair of horns. Venus has always been the brightest object in the sky other than the moon. Enheduanna must have noticed how Venus blazed beneath her giant father in the sky—an angry, brimming thing, as she still appears today. The sky is vast and unknowable but also one of the few things that has remained mostly the same, its changes often requiring millennia to perceive.

We don’t have much information about the function of poetry during Enheduanna’s lifetime, but writing and stargazing were deeply related pursuits. The goddess Nisaba was the deity of both scribes and stargazers, and in Sumerian, the word for star can also mean cuneiform sign. Poems were likely intoned by professional lamenters in elaborate temple performances, accompanied by bull-headed lyres with gemstone eyes played by esteemed musicians. If stargazing was an attempt to read the writing of the gods, poetry appears to have been an attempt to communicate with the divine. Enheduanna’s most recent translator, Sophus Helle, describes how Sumerian poetry attempted “to change the world, by invoking the gods and enlisting their help.”

Within this broader context, Enheduanna’s poems are more complex than mere glimpses into the night sky, framed by evocative parallelism. What is most relevant is not what she saw—stars like cuneiform signs, the sun as a giant beard—but rather how she might have used celestial imagery to summon Inanna’s attention and convince the goddess to save her. “Queen of all powers, downpour of daylight,” she begins her masterpiece. “Good woman wrapped in frightful light.” Her verses harness the sky, its power and radiance, to elevate her savior and flatter her muse. “She turns the midday heaven into a starry sky,” Enheduanna writes, suggesting that Inanna was not just a feature of the sky but the commander of its bright terrain.

Like the astronomers who came later, Enheduanna could have also used her celestial imagery as an instrument of power. Her father Sargon was king, but she also lived through the reigns of her other male relatives, including her brother Rimush, known for pioneering mass executions; her other brother Manishtusu, who seized unprecedented tracks of land from the Sumerians; and her nephew Naram-sin, the first ruler to crown himself a god. These rulers credit Ishtar, the Akkadian name for Inanna, for their military successes; her cult became so central to the Akkadian empire that a later chronicler refers to their dynasty as the Reign of Ishtar. Given this broader history, it’s possible Enheduanna hoped to see not only herself reflected in Inanna’s rise to supremacy, but also the story of her family’s triumph. Could she have seen the unprecedented victory of the Akkadian troops, who brandished shining copper weapons as they dominated Sumer? Many of her verses cast Inanna as a fearsome warrior—“let them know that you grind skulls to dust”—and over the next two thousand years, Ishtar became a figurehead of empire. King Ammisaquda’s predecessor King Ammiditana left behind a hymn where he praises the goddess in language that echoes Enheduanna’s work. “She grasps in her hand the destinies of all that exists.” he writes. “Who is it that could rival her grandeur?”

Even if her verses served imperial ends, they still thrum with intimacy. “I will let my tears stream free to soften your heart, as if they were beer,” she writes. Enheduanna is also the attested author of forty-two shorter poems called the Temple Hymns, dedicated to various temples across the Akkadian empire. In the colophon to this collection, she writes: “My king! Something has been born which had not been born before.” Helle argues that the Temple Hymns demonstrate a kind of “hymnic imperialism,” as these poems work to unify previously disparate cults into a poetic whole. The sky must have been brimming with possible metaphors for such a project. The Temple Hymns begin near the banks of the Persian Gulf with the earliest known Sumerian cities, like Eridu, which “sprouted with heaven and earth.” Her narrative travels north toward the newer Akkadian cities. Temples dot the marshland like a constellation. “You shine with the light of righteous rule,” she writes of the Moon God’s temple at Ur; while a temple in the northern city of Sippar dedicated to the Sun God is a “shining house.” In a poem that concludes the Temple Hymns, she describes the goddess Nisaba, deity of scribes and stargazers, as a “righteous woman of unmatched mind,” who “measures the heavens and outlines the earth.” And perhaps that’s also how Enheduanna saw herself. This new heavenly map turns the concept of empire into something as natural and inevitable as stars in the sky.

By the time the prophet Abraham was born in the city of Ur about a thousand years after Enheduanna died—five hundred years after the first astronomers tracked Venus—the Mesopotamians were renowned for their astronomical pursuits. It was the first civilization to predict eclipses, inscribe maps of the zodiac, and calculate the cycles of planets and stars. The Jewish-Roman historian Josephus claimed that Abraham himself was a famous astronomer, descended from generations of stargazers. According to Josephus, it was through Abraham’s observations of the heavens that he realized there must be a god controlling the cosmos. He decided that celestial bodies must be “subservient to Him that commands them.” And thus Abraham set off for Canaan. Given Enheduanna’s singular devotion to Inanna, it isn’t hard to imagine her having had similar thoughts when she observed the morning star and evening star from the summit of the Moon God’s temple. If Abraham was impressed by the intelligence underpinning the cosmos, Enheduanna seemed struck by the particular force of Inanna’s astral form, the way she “beamed with a passionate delight, like a downpour of moonlight.”

The astronomical practice Abraham left behind continued unbroken through Alexander the Great’s conquest of Babylon in 331 bc, when Mesopotamian science rapidly spread west across the Mediterranean and east toward the Indus Valley. As Pliny the Elder wrote in the second century in a clear feat of exaggeration, “the Babylonians had astronomical observations for 730,000 years inscribed on baked bricks” and numerous Greek writers, including Aristotle, credited the Babylonians with pioneering the celestial sciences. What first becomes visible in Enheduanna’s poetry—the attempt to capture the sky’s ungraspable forms in language—continues, for thousands of years, and forms the foundations of astronomy, astrology, and the very deciphering of the heavens.

As later generations of Mesopotamians calculate Venus’ positionality with increasing accuracy, as militarized empires dominate the region, scribes and kings continue to be moved by the dualistic and flickering form of Ishtar, whose cult influenced a wide array of Venus goddesses, including the Greek deity Aphrodite. Babylonian omens associate Venus’s appearance with periods of fertility and warfare, and Ishtar remains a favorite subject of literary compositions, appearing in contradictory guises as an impetuous warmonger, a young woman preparing for marriage, and a deity of lamentations, among many other manifestations.

Enheduanna drew parallels between heaven and earth in her poetry, but within the larger history of astronomy, her legacy seems to run parallel to the many innovations and works of literature composed in her wake. A text attributed to the Sumerian king Gudea, who ruled just a couple centuries after her death, describes Nisaba in terms that evoke the electric sense of possibility at the heart of Enheduanna’s legacy. “There was a woman—Who was she? Who was she not?” he asks. “A stylus of flaming silver she held in her hand / There was a tablet of heavenly stars on her knees, and she was consulting it.”