Installation of memorial poppies at the Tower of London, 2014.

In May 1919, as the Paris peace talks were making the world anew in the wake of World War One, the British government entrusted its foreign minister, Lord Curzon, with organizing a celebration for Germany’s signing of the treaty. The aristocratic Curzon, former Viceroy of India, wanted the world to know the British Empire had won. He planned four days of celebration—including a victory march and a naval pageant—alongside religious services and popular entertainment. But Curzon had badly misjudged the national mood. The French government had planned a simple military parade and a salute to an empty tomb; this struck the British prime minister, David Lloyd George (who despised Curzon), as more appropriate to the atmosphere of mourning.

Although some in the British government were concerned that the empty-tomb idea sounded too “Latin” for Protestant English tastes, the chief architect of the British war cemeteries, Sir Edwin Lutyens, was inspired by it. He sketched a cenotaph, with a coffin shape on top of a tapered pillar, which was quickly turned into a temporary monument of wood and plaster. Some 15,000 troops marched past the monument in Whitehall when Britain celebrated Peace Day on an unseasonably rainy day in the middle of July. In her diary, Virginia Woolf wrote, “It seems to me a servants festival; some thing got up to pacify & placate ‘the people.’” But glowing reports in the next day’s newspapers made it clear that the odd, nondenominational structure, which proclaimed only “The Glorious Dead” and the dates of the war, was an appropriate focus of national commemorative efforts.

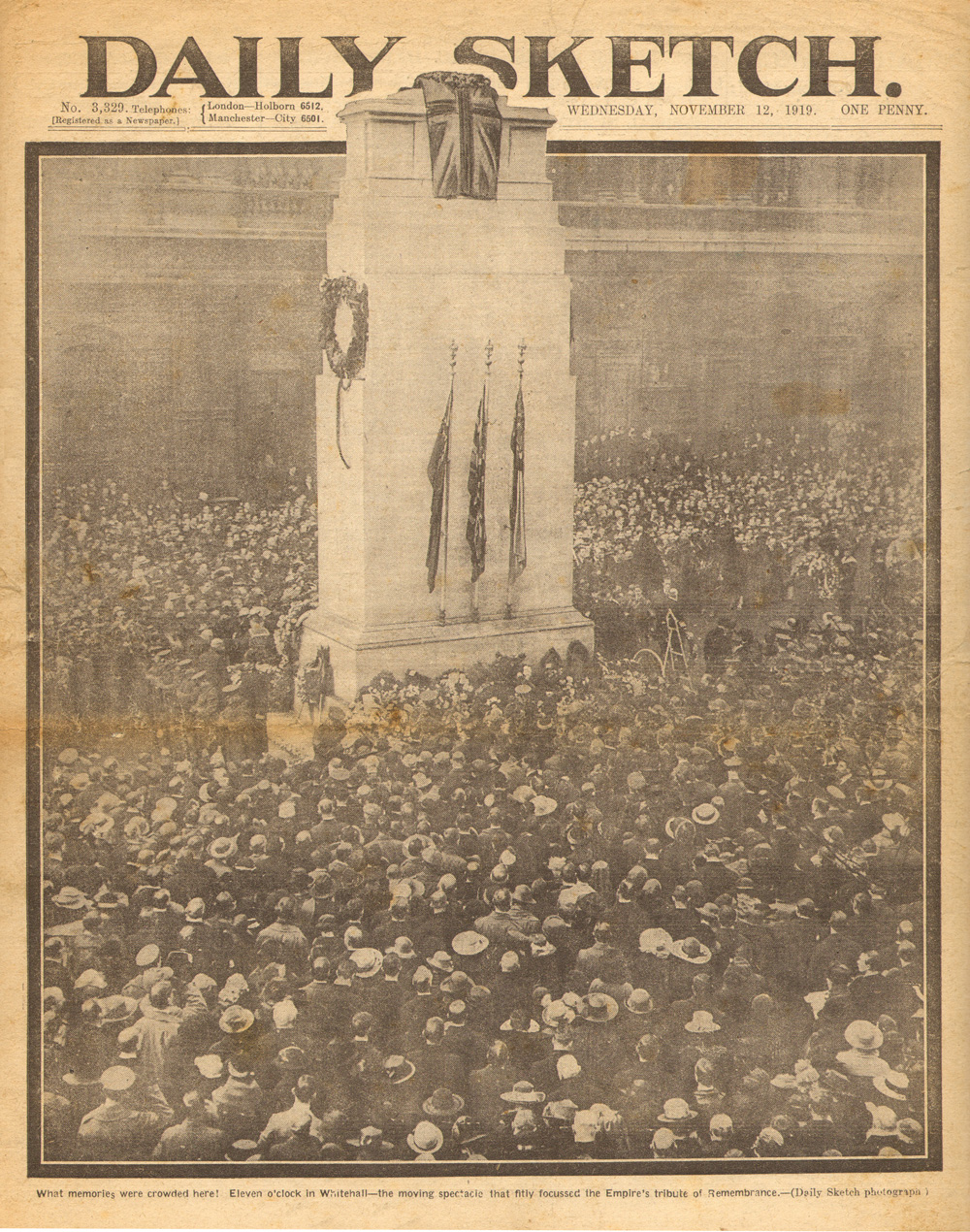

The July Peace Day in 1919 did not continue as the main date for national commemoration—November 11, 1918, the day the Armistice had been signed in a railroad carriage in France, carried more weight as the moment that the guns were silenced. One year later, at exactly 11 a.m. on November 11, 1919, the crowds gathered at the temporary cenotaph fell silent for two full minutes. One of the most enduring and powerful traditions of remembrance was born.

The idea had come a long way. In May 1918, the mayor of Cape Town, Sir Harry Hands, instituted a daily three-minute “pause” after the firing of the city’s traditional noonday gun, during which locals would stop to remember those who had died and the brutal fighting that was still going on. Among its observers was a prominent local writer and politician, Sir Percy Fitzpatrick, whose eldest son had been killed the previous year at Beaumetz on the Somme. Deeply moved by the silence, Fitzpatrick wrote to British newspapers in about it and eventually found the ear of George V, who was sympathetic and supportive. Fitzpatrick named four groups he thought would benefit from the ritual: the bereaved (who, despite his own grief, he imagined as female); children (who could learn from it); veterans; and the dead themselves, who would be joined in their silence.

Given how fiercely contested most other commemorative rituals and objects had been, with arguments still underway about iconography, form, location and meaning still ongoing, the silence, like the Cenotaph, was welcomed for its open-endedness of interpretation. A few days before Armistice Day, the King wrote in the Times that he hoped there would be “a complete suspension of all our normal activities. During that time, except in the rare cases where this may be impracticable, all work, all sound and all locomotion should cease, so that, in perfect silence, the thoughts of everyone may be concentrated on reverent remembrance of the Glorious Dead.”

The silence (or Silence, as it tended to be styled in the interwar years) stood at the center of Britain’s Armistice Day rituals. From the beginning it was timed to correspond with the ceremony at the Cenotaph at Whitehall, and was later broadcast from there by radio and then by television. It was important that it was a broadcast of silence, not simply a two-minute interruption in transmission: the tension of the silence carried over to the listeners. If it was observed in public, the Silence was simultaneously a performance of remembrance and an opportunity for private remembering. It is difficult to know whether the inviolable sanctity of the Silence was felt to be coercive or oppressive. At the same time, within that public silence, there was no way of controlling what people were actually thinking. Newspapers frequently carried scare stories of “violators” being forcibly silenced and shamed, but they were always careful to present these as the spontaneous reactions of fellow mourners, never as any kind of official punishment.

The idea of the Silence spread quickly from London to Canada and Australia and throughout the Empire. Two years later, according the Times, the ritual became—like the visually identical war cemeteries then being constructed—a way of connecting British remembrance efforts throughout the Empire: “From the jungles of India to the snows of Alaska, on trains, on ships at sea, in every part of the globe where a few British were gathered together, the Two Minute Pause was observed.” It was felt most powerfully in urban, industrial areas, where silence was a rarity—and also, where fears of political unrest in the wake of the Russian Revolution were most acute. Most commonly, a church bell broke the silence, but the use of other more jarring methods, including sirens and even artillery gunfire, is a reminder of how imperfectly the psychological effects of war were understood.

During the Armistice Day service, the silence was officially broken by a recitation of poetic verse written at the start of the war, Laurence Binyon’s 1914 poem “For the Fallen.” The fourth verse of the poem stood alone and became known as the “Remembrance Ode.”

They shall not grow old, as we that are left grow old

Age shall not weary them, nor the years condemn

At the going down of the sun, and in the morning

We will remember them.

The last line of the verse was (and still is) repeated aloud by the congregation, as a kind of “amen” that divorces the phrase from its original context and turns it into a public commitment to remember. In the original poem, however, the line is more ambiguous: “At the going down of the sun, and in the morning” implies that this remembering will happen daily, insistently, whether we choose it or not. Remembering may be something that happens to us, not something we choose.

The role of veterans in the observation of the Silence was fraught. As grieving tended to be seen as a feminine role, or at least a civilian one, it was difficult for young men to express their grief in public. Their commemorations of lost comrades tended to take place in more exclusively masculine spaces: in pubs, and especially in army social clubs, where reminiscence and nostalgia were acceptable ways to convey bereavement. The British Legion, the main veterans’ organization, pressured the government to make November 11 a national holiday, as it was in France and the United States, but they failed in their efforts. By contrast, when Woodrow Wilson described his reasons for making Armistice Day a national holiday, his comments focused specifically on veterans, not the bereaved:

To us in America, the reflections of Armistice Day will be filled with solemn pride in the heroism of those who died in the country’s service and with gratitude for the victory, both because of the thing from which it has freed us and because of the opportunity it has given America to show her sympathy with peace and justice in the councils of the nations.

“Pride,” “heroism,” and “victory” were less common in British commemorations, where the scale of loss had rendered such ideas suspect. In some parts of Britain, the worsening status of veterans during the recession in the early part of the twenties spurred protests against Armistice Day and the Silence. By early 1922, veterans made up over two-thirds of the male unemployed. Official efforts to extend employment relief were driven as much by fear of unrest as by a sense of what the nation owed to these survivors. The veterans knew that Armistice Day was a powerful focus for their organizing. In 1921 Liverpool veterans disrupted the Silence in protest, and in Dundee, the fears of Communist infiltration into veteran groups seemed confirmed when veterans began singing “The Red Flag.” But there was another reason many veterans did not identify with the solemn rituals of Armistice Day: November 11 had been a day of celebration, and many veterans tried to re-create 1918’s raucous, relief-driven parties with “Victory Balls” that toasted the dead and their own survival.

Was it better to celebrate or to mourn? When Victory Balls met resistance in the press, the problem became more complicated. To whom did Armistice Day, and its rituals, belong? Was the Silence a ritual of prayer by another name? It tended to be seen as such in America, where it never caught on nationally out of fear that at its base, the moment of silence was an attempt to smuggle religion into the public sphere. At the same time, the Cenotaph and its ceremonies were not securely Christian either. The church was often wary of the power of Armistice Day as a kind of folk observance, as an attempt to commune with the dead. Its power, however, lay in its absence of nationalist or religious dogma (Laurence Binyon, who composed the “Remembrance Ode,” was a Quaker.) Amid all the competing narratives, however, the most powerful remained that two-minute silence, in which a prayer could be offered, or a mute protest lodged, and where no government or church could intrude.