Autumn Maples with Poem Slips, by Tosa Mitsuoki, c. 1675. The Art Institute of Chicago, Kate S. Buckingham Endowment.

This summer, Lapham’s Quarterly is marking the season with readings on the subject or set during its reign. Check in every Friday until Labor Day to read the latest.

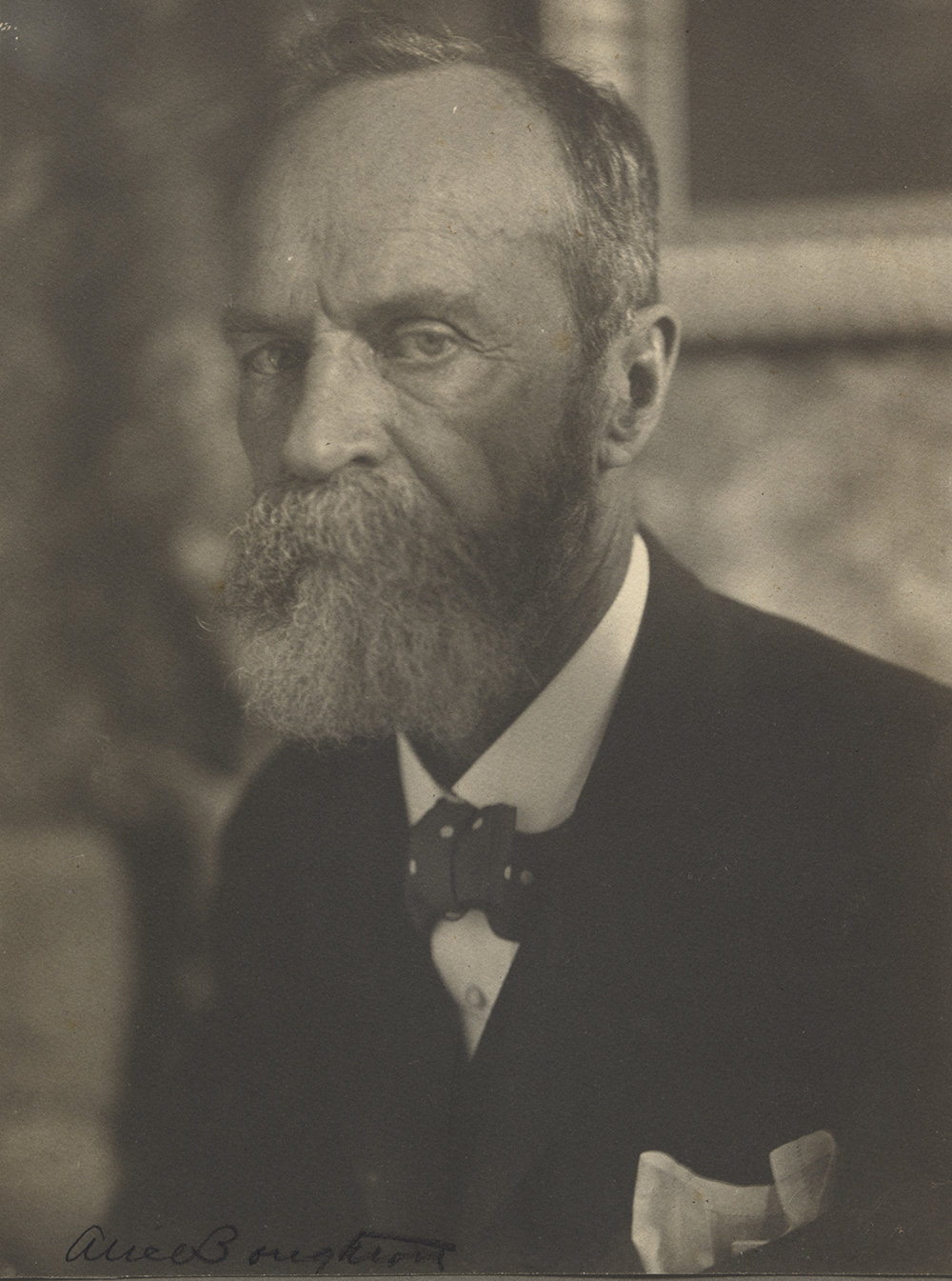

During the summer of 1896 William James read War and Peace for the first time, writing his younger brother Henry James in June that “Tolstoy is immense!” He was fatigued by the “overlabored descriptions and excessive explanations. But with it all an earnestness and enthusiasm for getting it said as well as possible, a richness of epithet, and a warmth of heart that makes you like him, in spite of the unmanliness of all the things he writes about. I suppose there is a stratum in France to whom it is all manly and ideal, but he and I are, as Rosina says, a bad combination.”

He spent the summer traveling the Northeast, giving lectures and taking in local splendors. “I see no need of going to Europe,” he wrote to his wife Alice in July, “when such wonders are close by.” It was a season of many letters—perhaps too many, as he told his brother when it was over and the Harvard semester was beginning.

To Henry James

Burlington, VT, September 28, 1896

Dear Henry,

The summer is over! Alas! Alas! I left Keene Valley this am where I have had three life-and-health-giving weeks in the forest and the mountain air, crossed Lake Champlain in the steamer, not a cloud in the sky, and sleep here tonight, meaning to take the train for Boston in the am and read Kant’s Life all day, so as to be able to lecture on it when I first meet my class. School begins on Thursday—this being Monday night. It has been a rather cultivating summer for me, and an active one, of which the best impression (after that of the Adirondack woods, or even before it) was that of the greatness of Chicago. It needs a Victor Hugo to celebrate it. But as you won’t appreciate it without demonstration, and I can’t give the demonstration (at least not now and on paper), I will say no more on that score!

Alice came up for a week, but went down and through last night. She brought me up your letter of I don’t remember now what date (after your return to London, about Wendell Holmes, Baldwin, and Royalty, etc.), which was very delightful and for which I thank. But don’t take your epistolary duties hard! Letter writing becomes to me more and more of an affliction, I get so many business letters now. At Chicago, I tried a stenographer and typewriter with an alleviation that seemed almost miraculous. I think that I shall have to go in for one some hours a week in Cambridge. It just goes “whiff” and six or eight long letters are done, so far as you’re concerned. I hear great reports of your “old things,” and await the book. My great literary impression this summer has been Tolstoy. On the whole his atmosphere absorbs me into it as no one’s else has ever done, and even his religious and melancholy stuff, his insanity, is probably more significant than the sanity of men who haven’t been through that phase at all.

Good night. Leb’ wohl!

W.J.

The Varieties of Religions Experience, an edited volume of the celebrated lectures William James had given at the University of Edinburgh in 1901 and 1902, were published in June 1902. He told his friend Fanny Morse in May 1901 that his audiences “sit as still as death and then applaud magnificently, so I am sure the lectures are a success.” James had spent much of the previous two years in Europe, where he was quite ill, and he had not entirely recuperated, despite (or perhaps because of) his busy schedule. But Edinburgh, “spiritually much like Boston, only stronger and with more temperament in the people,” was lovely, he thought. “Beautiful as the spring is here,” James wrote to Morse, “the words you so often let drop about American weather make me homesick for that article.”

It is blasphemous, however, to pine for anything when one is in Edinburgh in May and takes an open drive every afternoon in the surrounding country by way of a constitutional. The green is of the vividest, splendid trees and acres, and the air itself an object, holding watery vapor, tenuous smoke, and ancient sunshine in solution, so as to yield the most exquisite minglings and gradations of silvery brown and blue and pearly gray. As for the city, its vistas are magnificent.

The following year, after James had returned to an American climate, with not a single “Lord Somebody” to ruin his concentration, he sent Morse a review of his summer at its close. Fall and its many obligations were already encroaching on his idyll.

To Miss Frances R. Morse

Intervale, NH, September 18, 1902

Dearest Fanny,

How long it is since we have exchanged salutations and reported progress! Happy the country which is without a history! I have had no history to communicate, and I hope that you have had none either, and that the summer has glided away as happily for you as it has for us. Now it begins to fade toward the horizon over which so many ancient summers have slipped, and our household is on the point of “breaking up” just when the season invites one most imperiously to stay. Dang all schools and colleges, say I.

I may possibly make out to stay up here till the Monday following, and spend the interval of a few days by myself among the mountains, having stuck to the domestic hearth unusually tight all summer.

We have had guests—too many of them, rather, at one time for me—and a little reading has been done, mostly philosophical technics, which, by the strange curse laid upon Adam, certain of his descendants have been doomed to invent and others, still more damned, to learn. But I’ve also read Stevenson’s letters, which everybody ought to read just to know how charming a human being can be, and I’ve read a good part of Goethe’s Gedichte once again, which are also to be read so that one may realize how absolutely healthy an organization may every now and then eventuate into this world. To have such a lyrical gift and to treat it with so little solemnity, so that most of the output consists of mere escape of the over-tension into bits of occasional verse, irresponsible, unchained, like smoke wreaths! It du give one a great impression of personal power.

Goodbye!

Dear Fanny—you see how moldy I am temporarily become. The moment I take my pen, I can write in no other way. Write thou, and let me know that things are greener and more vernal where you are. Alice would send much love to you, were she here. Give mine to your mother, brother, and sister-in-law, and all.

Your loving,

W.J.

Read the other entries in this series: Charles Dudley Warner, I.A.R. Wylie, Jennie Carter, Virginia Woolf, Fyodor Dostoevsky, Willa Cather, Thomas Jefferson, Fridtjof Nansen, Elizabeth Robins Pennell, Izumi Shikibu, Hilda Worthington Smith, Mark Twain, and Johann Wolfgang von Goethe.