In Siena they have Il Palio, a bareback horse-race run twice every summer between various city wards. The horses circle the piazza three times, often discarding their riders along the way. The race is usually over in two minutes or less; interfering with rivals is encouraged. Three hundred miles to the north, in Ivrea, they throw oranges at one another for several days just before Lent to celebrate resistance against an assortment of semilegendary tyrants, including the twelfth-century nobleman Ranieri di Biandrate, who, the story goes, attempted to exercise droit du seigneur with a local woman. Before they could ship oranges up from Sicily, they threw apples; before apples, they threw beans.

In the Swiss canton of Valais, just across the border from northern Italy, they host combats de reines: Two cows with blunted horns fight in a ring, each winner taking on the next until a final “queen of queens” emerges victorious. Sometimes this takes a while, as the animals are not always inclined to fight. Any cow who runs out of the ring or otherwise declines to do battle is declared the loser. Swiss cattle breeds like the Hérens are distinctively small and aggressive; fights often break out between members of the herd in order to establish dominance. But it is nonetheless difficult to start quarrels on demand.

Cow-fighting, unlike bullfighting, is relatively bloodless; when cows fight, it is by putting their heads together and pushing. The loser merely slides out of the ring and into ignominy. This is practiced not only in Valais but among the Italians of the nearby Aosta Valley, and the French in parts of Savoy.

There are mock wars, mock rebellions, mock street fights, burlesque animal fights, and more than a few real races, but almost always what is being travestied is war and rivalry. It is not like this in Venice; in Venice, the whole city gets married. Thirty-nine days after Easter on Ascension Day, the mayor leads a naval procession from the lagoon into the Adriatic for the Sposalizio del Mare, in which he tosses a gold ring into the water and ceremonially marries the sea.

Incidentally, and while we are at sea, it’s a myth that ship captains are automatically licensed to officiate weddings (except in Japan). The mistaken idea that captains are empowered to marry couples is old enough, and widespread enough, that the U.S. Navy Regulations of 1913 had to specifically remind officers otherwise:

The commanding officer of a ship shall not perform a marriage ceremony on board nor shall he permit one to be performed when the ship is outside of the territory of the United States, except in accordance with the local laws and laws of the state, territory, or district in which the parties are domiciled, and in presence of a minister or consul of the United States, who has consented to issue the certificates and make the returns required by the consular regulations.

There is as yet no concrete source identifying the origin of this belief.

Back to Venice: The Adriatic is a protected cul-de-sac of the Mediterranean Sea, sheltered between Italy in the west and the Balkans in the east. There’s an immediate visual distinction between the two coastlines. With the exception of the Venetian lagoon in the extreme northwest, the Italian shore is relatively uniform, flat, smooth, and low, while the Balkan side is broken into an intricate series of barrier islands, fjords, rias, straits, and inlets.

For nearly eight hundred years, beginning in the ninth century, this distinction was more physical than political: everything the Adriatic touched was Venice. This included the city itself, known as the Dogado, her mainland territories in Italy, the Domini di Terraferma, and her overseas possessions, the Stato da Màr, or “State of the Sea.” First the Mediterranean salt trade, then the medieval slave trade, then the Crusades and the decline of the Byzantine Empire enriched Venice and enlarged her borders. By the fifteenth century the Stato da Màr stretched as far as Cyprus, Crete, and the Peloponnese. By the eighteenth century it had been constricted into the Venetian hinterlands and a thin slice of the Dalmatian coast. Today, only Venice is Venice.

An empire at sea (as opposed to the more common overland type of empire, where maritime possessions are incidental) is sometimes called a thalassocracy. It is no surprise that the Mediterranean has produced the greater part of the world’s thalassocracies over the last few millennia. But most Venetian citizens, even at the high-water mark of her imperial influence, did not take to the sea. How then to cultivate a sense of shared social drama and collective experience?

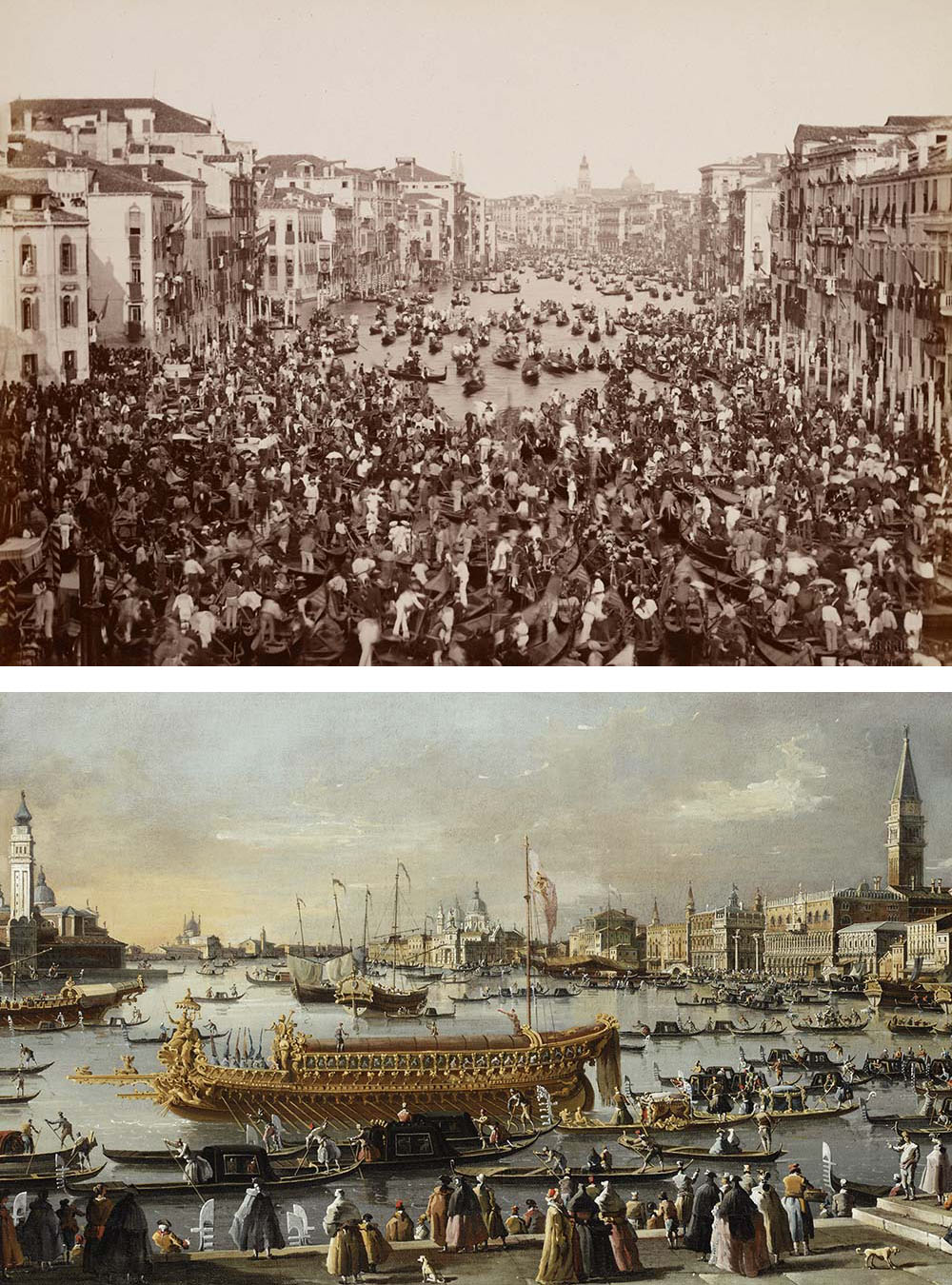

Depending on how far back you mark the origin of the ceremony, the city has sent out a representative to wed the sea for anywhere between 850 to 1,100 years, with a few notable gaps during the eleventh, nineteenth, and twentieth centuries. For most of this period the doge, the elected leader of the republic, married the sea on the city’s behalf. The ceremony began with the doge traveling on the bucentaur, his particular ceremonial barge, to where the lagoon meets the Adriatic. (There were four major bucentaurs built for the doges during the life of the republic: one in 1311, one in 1526, one in 1606, and the last in 1727. This averages out to one new bucentaur for every thirty doges. The final bucentaur was the most magnificent, with two decks and forty-eight windows, trimmed in gold leaf, and bearing a sculpture of Mars with two lions. French soldiers set it on fire in 1798. There’s been an in-progress attempt at restoration since 2008 by the Venetian cultural organization Fondazione Bucintoro.) On the bucentaur’s deck, the Patriarch of Venice (the city’s bishop) blessed a ring in front of a papal delegation, representatives from the Venetian Council, and international ambassadors and dignitaries. Then the doge threw the ring into the water, saying, “We wed thee, O sea, as a sign of sure and perpetual dominion,” before being rowed back to shore for the rest of the Feast of the Ascension, which included a fair, the ringing of bells, cannonades, further naval parades, the celebration of Mass, gondola races, and a banquet at the doge’s palace.

For as long as people have been setting out to sea, some of them have thrown valuable little objects into it at the start of their journey, in the hopes of purchasing a safe return. Venetians credit Doge Pietro II Orseolo, whose reign spanned the end of the tenth century and the beginning of the eleventh, with launching both the Ascension festival and the city’s eastward expansion. French historian Salomon Reinach tried to backdate the wedding ceremony to classical antiquity in his 1905 book, Cults, Myths and Religions. Polycrates, the sixth-century-bc tyrant of Samos, was said by Herodotus to have thrown his seal ring, an emerald set in gold, into the Aegean Sea in order to avoid the jealousy of the gods. St. Helena, mother of Constantine, supposedly hurled one of the nails from the true cross into the Adriatic on a voyage from Constantinople to Rome, intending to ward off storms.

We are not persuaded, as Reinach was, that the marriage to the Adriatic was a pagan tradition subsumed by the Church. He was a contemporary of the Cambridge Ritualists and archaeologist Margaret Murray, whose “witch-cult hypothesis” (that the European witch trials of the early modern era were in fact the concerted suppression of a widespread pagan religious movement that had secretly survived Christianization) would profoundly influence the development of Wicca. There is no contemporary evidence suggesting anything like a pre-Christian origin for the ceremony.

The marriage had become a regular occurrence by the 1170s under the thirty-ninth doge, Sebastiano Ziani. According to an oft-repeated but probably apocryphal story, the pope gave him the ring and instructed him to marry the sea in the first place. By the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the opening of Atlantic sea routes and ascendency of the Ottoman Empire meant that the Most Serene Republic’s political and naval dominance began to give way. Venice lost Crete, Corinth, its footholds in the Ionian islands, and control of the Morea peninsula. The city did not, however, lose the cultural appeal that had always drawn visitors, and the Wedding to the Sea, which had once served as an overwhelming display of imperial power and majesty, began to attract early tourist attention as a beautiful curiosity.

By rough count, and taking the gaps into account when possible, there are between 500 and 750 gold rings at the bottom of the Venetian lagoon. Prior to 1965, no one from Venice had married the sea since 1797, the year Napoleon dismembered the Most Serene Republic and forced, then accepted, the abdication of Ludovico Manin, the 120th and last doge.1 The modern ceremony was revived to promote tourism. Today’s leaders of course must do without the city’s “sure and perpetual dominion of the sea.” The present mayor, Luigi Brugnaro, has married the sea on several occasions since his inauguration in 2015. One can watch his predecessor make the vow in 2012 on YouTube. Brugnaro publicly feuded with Elton John after banning a number of books about gay couples from Venetian libraries his first year in office, and promised the newspaper La Repubblica, “There will never be a gay pride in my city. Let them go and do it in Milan.” Venice has never had a woman mayor. Possibly the idea of a woman marrying the same sea as more than a hundred male predecessors could evoke the specter of gay marriage.

There are no remaining Most Serene Republics. San Marino is officially, and merely, “the Republic of San Marino.” The Republic of Genoa—which preferred to style itself “Superb” rather than “Serene”—and the Most Serene Republic of Lucca were both dismantled by Napoleon. Interestingly, the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, which had formally united the two states under one monarch in 1596, was known as “the Most Serene Commonwealth of Both Nations” until its dissolution in 1795. Poland would itself celebrate a handful of Weddings to the Sea in 1920 and 1945 to commemorate regained access to the Baltic as an independent nation, although it never caught on as a regular habit. The New York Times covered the ceremony with the headline poles symbolize union with the sea. General Józef Haller served as his country’s representative. The Times reported: “General Haller stepped forward, drew from his finger a golden ring, and threw it far out into the water, saying as he did so, ‘As Venice so symbolized its marriage with the Adriatic so we Poles symbolize our marriage with our dear Baltic Sea.’”

For a few years in the 1960s and 1970s, the New York City phone book included a number for “the Most Serene Federal Republic of Montmartre” between 39th and 59th Street, paid for by theater promoter Barry Alan Richmond, but this micronation-cum-work of performance art was struck from the lists after the Public Service Commission ruled in favor of New York Telephone in 1977. If it is slightly less impressive to have been brought down by the New York phone book than by Napoleon, the underlying lesson seems to be the same: Big fish eat smaller fish, and there will always be a bigger fish.

The doge was not unique to Venice. Genoa picked a doge of its own in the fourteenth century, as did, from time to time, Amalfi and Senarica. Venice’s doge was an elected position, usually held for life, and once carried extensive powers. The city was known as a “crowned republic,” an inexact term sometimes used today as a synonym for “constitutional monarchies” like the United Kingdom, while at other times used more specifically to refer to any city–state led by a doge. The Venetian doge was often styled “His Serene Highness,” a form of address that survives today only among the Princely House of Liechtenstein and the House of Grimaldi in Monaco. He was also peculiarly surveilled and restricted in his exercise of influence, more so than most of his royal contemporaries; his son was never allowed to succeed him, nor could he name any other unrelated successor.

The wife of the doge, known as the dogaressa, was unique to Venice; women who married doges in other cities were simply “the doge’s wife.” The dogaressa was also often crowned upon accession and swore her own version of the oath of office, the promissione ducale, although she had no particular political powers. It is unclear if some or most of the dogaressas attended the Sposalizio del Mare; a crowned woman appears on one of the ships in some paintings of the ceremony, but such depictions are not necessarily definitive. The promissione was, over time, so loaded with promises to honor restrictions on what the doge and dogaressa were permitted to do that by the time of Ludovico Manin’s inauguration in 1789, the document was over three hundred pages long.2

Here is how you select a doge:

Choose thirty members of the Great Council, the primary governing body of Venice, whose membership is restricted to families enrolled in the Libro d’Oro, or “Golden Book of Venetian Nobility,” by drawing lots. Now reduce them to nine, again by drawing lots.

Ask the remaining nine to name forty new nominees. Now reduce those nominees to twelve, again by lot. Ask those twelve to name twenty-five nominees. Reduce the twenty-five to nine by drawing lots.

Ask the remaining nine to name forty-five nominees. It should go without saying that each new batch of nominees cannot include names from a previous round. Reduce those forty-five nominees to eleven by drawing lots. Ask the remaining eleven to name forty-one nominees. Sequester the council of forty-one and ask them to choose the doge from the Libro d’Oro by writing names on slips of paper.

The preceding Benny Hill sequence was created to randomize the final electing body, so as to make it more difficult for certain factions or interests to covertly select a candidate in advance.

There are certain things only a king can do. In both France and England, the royal touch was understood to heal scrofula, although neither country could agree on which king first demonstrated healing hands. (England thought it was Edward the Confessor, the French Robert II, although some went as far back as Clovis I.) English kings also blessed and distributed “cramp-rings” as cures for cramps and epilepsy. In Hungary, monarchs cured jaundice, while in Castile they could exorcise demons.

Venice did not want the doge to become a king. Thus the procedure for electing a new doge became increasingly elaborate over the years (“torturous, ridiculous, and profound,” per Anthony Gottlieb, writing in 2010). Additional councils and lot-casting were added throughout the medieval period to complicate and obfuscate the process, baffling any noble families that might have otherwise tried to use repeat candidates to create an unofficial dynasty. The fifty-fifth doge, Marino Faliero, was executed in 1355 for trying to overthrow the Council of Ten. But this increase in surveillance, along with the decline in political powers and the addition of ceremonial responsibilities, seems to have been for the best, at least as far as the doges were concerned. Doges four, five, and six were all blinded and exiled, while the eighth and ninth were exiled (the ninth later beheaded anyway), the twelfth arrested and forcibly shaved bald, the thirteenth assassinated, the sixteenth killed in wartime, the twenty-second burnt alive in his own palace by the people of the city, the twenty-seventh arrested, forcibly shaved, and exiled, the thirty-eighth murdered. Faliero was not only executed but also had his paintings and coat of arms painted over in black throughout the city. Yet from the 1350s onward, most doges died from natural causes. Their survival rates improved as they acquired more ritual status. Even Napoleon allowed the last doge to take early retirement.

Taking into account the automatic reduction in pomp and dignity that comes from watching a recording of a civic pageant on YouTube, there’s still an undeniable something about the Wedding to the Sea. It’s a lot of fun, and frankly, more local politicians ought to be ceremonially married to regional landmarks. And while the Fondazione Bucintoro has offered no updates on the restoration of the ducal barge since its 2008 announcement, one can always hope that the bucentaur is just a few last-minute gilt touches away from being relaunched. But watching a mayor in a suit pledge to marry the sea, when he is at absolutely zero risk of being shaved bald by an angry Venetian mob should he fail to make them happy, doesn’t have the same ring to it.

1 There have been 266 popes, according to the Catholic Church’s own reckoning. 120 doges is nothing to sneeze at.↩

2 The doge had to promise to support himself financially, not to leave the palace without permission, and not to open letters or conduct meetings unsupervised by councilors. In 1401 the Great Council passed a law forbidding the doge from using his bucentaur for private purposes.↩