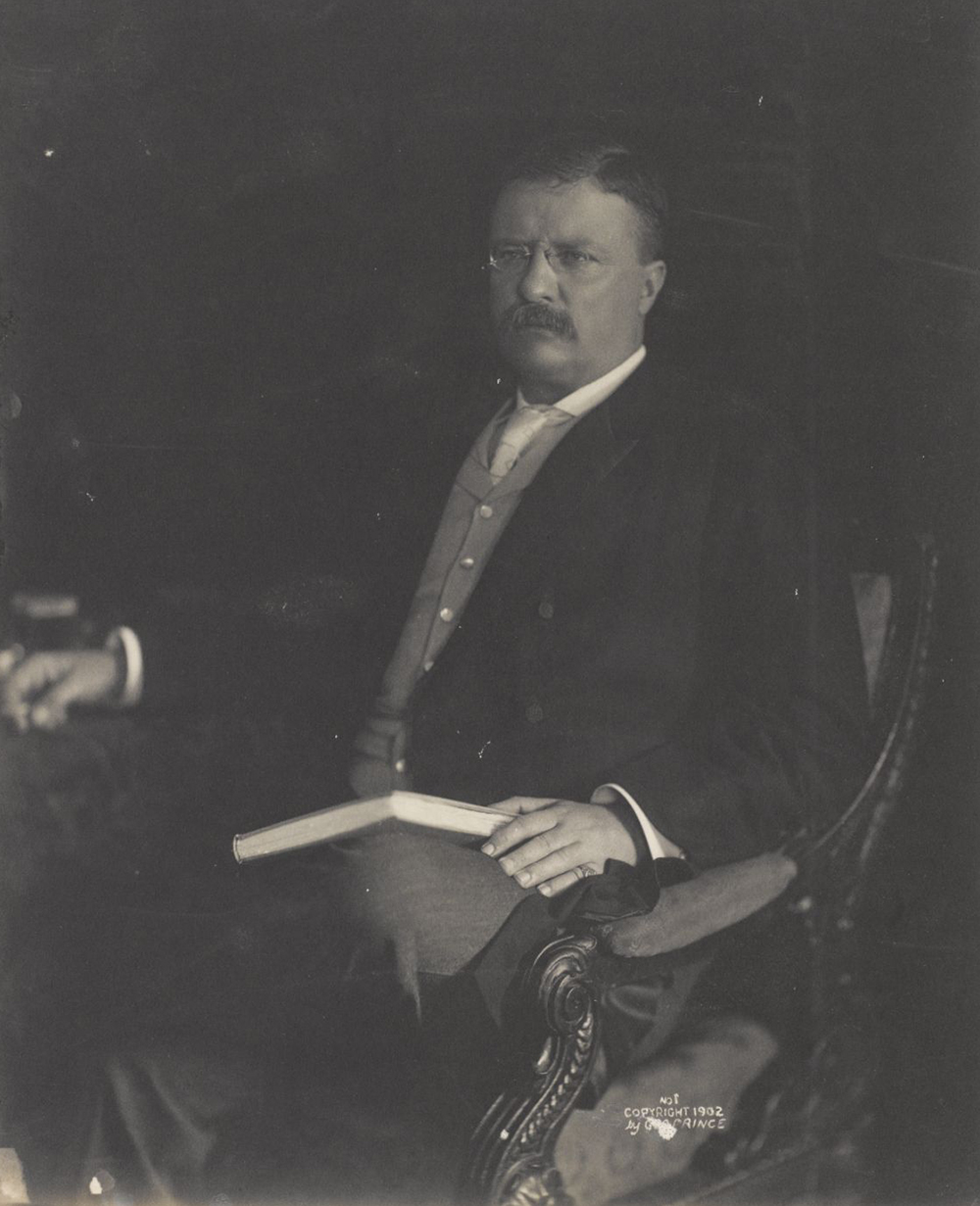

Library at Sagamore Hill, c. 1912. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

In 1915 former president Theodore Roosevelt wrote an article for Ladies’ Home Journal about the books he had read over his life and how he went about choosing them. He began by lowering expectations for whatever book recommendations might follow, as he had no way of assessing the character or taste of his future readers. “I am afraid my answer will not be so instructive as it ought to be,” he explained, “for I have never followed any definite plan in reading; and it seems to me that no plan can be laid down that will be generally applicable.”

If a man is not fond of books, to him reading of any kind will be drudgery. I most sincerely commiserate such a person, but I do not know how to help him. If a man or a woman is fond of books he or she will naturally seek the books that the mind and soul demand. Suggestions of a possibly helpful character can be made by outsiders, but only suggestions; they will probably be helpful about in proportion to the outsider’s knowledge of the mind and soul of the person to be helped.

He had much more to say on the futility of book recommendations in his list of book recommendations:

The equation of personal taste is as powerful in reading as in eating; and within certain broad limits the matter is merely one of individual preference, having nothing to do with the quality either of the book or of the reader’s mind. I like apples, pears, oranges, pineapples, and peaches. I dislike bananas, alligator pears, and prunes. The first fact is certainly not to my credit, although it is to my advantage; and the second at least does not show moral turpitude. At times in the tropics I have been exceedingly sorry I could not learn to like bananas, and on roundups, in the cow country in the old days, it was even more unfortunate not to like prunes; but I simply could not make myself like either, and that was all there was to it.

Despite the disclaimers that literary cilantro might lurk in future paragraphs, Roosevelt—who read constantly and peppered his conversation and writing with literary references—went on to offer some book recommendations. Below are some of those books, as well as others described in his diaries, letters, and many published works.

Books with Happy Endings

Roosevelt would have admired the frames that keep Hallmark holiday movie plots aloft. In 1915, a year with a racist president, crescendoing war, and the suppression of civil rights, sometimes escapism was key.

Of course, I know that the best critics scorn the demand among novel readers for “the happy ending.” Now, in really great books, in an epic like Milton’s, in dramas like those of Aeschylus and Sophocles, I am entirely willing to accept and even demand tragedy, and also in poetry that cannot be called great. But not in good readable novels, of sufficient length to enable me to get interested in the hero and heroine!

There are enough horror and grimness and sordid squalor in real life with which an active man has to grapple; and when I turn to the world of literature—of books considered as books, and not as instruments of my profession—I do not care to study suffering unless for some sufficient purpose. It is only a very exceptional novel which I will read if He does not marry Her; and even in exceptional novels I much prefer this consummation. I am not defending my attitude. I am merely stating it.

He did not necessarily have consistent taste in happy endings, having confessed to finding Jane Austen a slog. Roosevelt offered a self-deprecating example of his kind of happy ending in his Autobiography:

Aside from the masters of literature, there are all kinds of books which one person will find delightful, and which he certainly ought not to surrender just because nobody else is able to find as much in the beloved volume. There is on our bookshelves a little pre-Victorian novel or tale called The Semi-Attached Couple. It is told with much humor; it is a story of gentlefolk who are really gentlefolk; and to me it is altogether delightful. But outside the members of my own family I have never met a human being who had even heard of it, and I don’t suppose I ever shall meet one. I often enjoy a story by some living author so much that I write to tell him so—or to tell her so; and at least half the time I regret my action, because it encourages the writer to believe that the public shares my views, and he then finds that the public doesn’t.

Charles Dickens

On October 31, 1880, twenty-two-year-old Roosevelt was sitting at home with Alice, his wife of four days, reading aloud from the Bible, The Pickwick Papers by Charles Dickens, Quentin Durward by Walter Scott, and The Newcomes by William Thackeray. Two days later, Roosevelt went to cast his first vote for president: James Garfield over Winfield Scott Hancock. Many years later, when Roosevelt took a trip to Africa, he brought along a library of fifty-nine books to keep him company, rebinding them in pigskin to keep them safe from exposure to the elements. (“Often my reading would be done while resting under a tree at noon,” Roosevelt wrote of his Pigskin Library, “perhaps beside the carcass of a beast I had killed, or else while waiting for camp to be pitched; and in either case it might be impossible to get water for washing. In consequence the books were stained with blood, sweat, gun oil, dust, and ashes; ordinary bindings either vanished or became loathsome, whereas pigskin merely grew to look as a well-used saddle looks.”)

Dickens—both The Pickwick Papers and Our Mutual Friend—Thackeray, the Bible, and Scott all came along for the ride. He reread them often.

At the end of Roosevelt’s life, after he had voted for many more presidents, the Dickens book he tended to press into people’s hands was not The Pickwick Papers but instead Martin Chuzzlewit, a novel loved by its creator and few others. In it he saw a comforting reminder that his age was not alone in its utter inanity, as he explained in his Ladies’ Home Journal article:

Books of more permanent value may, because of the very fact that they possess literary interest, also yield consolation of a nonliterary kind. If any executive grows exasperated over the shortcomings of the legislative body with which he deals, let him study Macaulay’s account of the way William was treated by his parliaments as soon as the latter found that, thanks to his efforts, they were no longer in immediate danger from foreign foes; it is illuminating. If any man feels too gloomy about the degeneracy of our people from the standards of their forefathers, let him read Martin Chuzzlewit; it will be consoling.

If the attitude of this nation toward foreign affairs and military preparedness at the present day seems disheartening, a study of the first fifteen years of the nineteenth century will at any rate give us whatever comfort we can extract from the fact that our great-grandfathers were no less foolish than are we.

According to the latest inventory of books at the Roosevelt family home at Sagamore Hill on Long Island,1 there are twenty-two volumes of Dickens in the library. Several of the books have been worn to near extinction, dirty and stained, chapters torn asunder.

Abraham Lincoln

On October 2, 1903, Roosevelt wrote a letter to his son Kermit. He said he was glad his son was playing football but warned him not to let sports distract from his studies too much.

There! you will think this a dreadfully preaching letter! I suppose I have a natural tendency to preach just at present because I am overwhelmed with my work. I enjoy being president, and I like to do the work and have my hand on the lever. But it is very worrying and puzzling, and I have to make up my mind to accept every kind of attack and misrepresentation. It is a great comfort to me to read the life and letters of Abraham Lincoln. I am more and more impressed every day, not only with the man’s wonderful power and sagacity, but with his literally endless patience, and at the same time his unflinching resolution.

Roosevelt answered the question of what presidents should read in his Autobiography. The short answer: everything.

Now and then I am asked as to “what books a statesman should read,” and my answer is, poetry and novels—including short stories under the head of novels. I don’t mean that he should read only novels and modern poetry. If he cannot also enjoy the Hebrew prophets and the Greek dramatists, he should be sorry. He ought to read interesting books on history and government, and books of science and philosophy; and really good books on these subjects are as enthralling as any fiction ever written in prose or verse. Gibbon and Macaulay, Herodotus, Thucydides and Tacitus, the Heimskringla, Froissart, Joinville and Villehardouin, Parkman and Mahan, Mommsen and Ranke—why! there are scores and scores of solid histories, the best in the world, which are as absorbing as the best of all the novels, and of as permanent value. The same thing is true of Darwin and Huxley and Carlyle and Emerson, and parts of Kant, and of volumes like Sutherland’s Growth of the Moral Instinct, or Acton’s Essays

Leo Tolstoy

In April 1886, Roosevelt was living in the Dakota Territory, chasing after boat thieves and reading Russian literature. He told his sister Corinne that he could not decide if he could recommend the book he had just finished in good faith.

I brought Anna Karenina along on the trip and have read it through with very great interest, I hardly know whether to call it a very bad book or not. There are two entirely distinct stories in it; the connection between Levin’s story and Anna’s is of the slightest, and need not have existed at all.

However, he conceded,

Tolstoy is a great writer. Do you notice how he never comments on the actions of his personages? He relates what they thought or did without any remark whatever as to whether it was good or bad, as Thucydides wrote history.

Mayne Reid

Roosevelt was a sickly, asthmatic child, often cooped up in his family townhouse near Gramercy Park. To pass the time, he vacuumed up every nearby book, especially those that had to do with natural history and birds. As he later wrote in his Autobiography,

Among my first books was a volume of a hopelessly unscientific kind by Mayne Reid, about mammals, illustrated with pictures no more artistic than but quite as thrilling as those in the typical school geography. When my father found how deeply interested I was in this not very accurate volume, he gave me a little book by J.G. Wood, the English writer of popular books on natural history, and then a larger one of his called Homes Without Hands. Both of these were cherished possessions. They were studied eagerly; and they finally descended to my children.

Reading The Boy Hunters was a memory that many men of Roosevelt’s age shared, although they might not recommend the experience to others—and clearly didn’t, as Reid has been almost completely forgotten. When Reid died in 1883, The Spectator in London said he

could not analyze a character at all, and never created one…Nor could he paint his lay figures in a very lifelike way. Good and bad, his Mexicans, men and women, and mountaineers, and American desperadoes, and faithful Indians, and villainous bandits, are all alike,—and a little same, and not a little tiresome. They have qualities, but not characters, and move like marionettes. They all go through wonderful adventures, and if they had all got killed in them, as about three-fourths of them did, nobody would have cared.

The magazine concluded, however,

We see no harm in the enjoyment; it is only “Jack, the Giant Killer” for the grown-ups; and we believe firmly that someday romance will again be a widely popular form of fiction. Man grows gloomier and gloomier, but the childlike element in him is happily not dead yet.

For those who were about to call out any obvious gaps in his childhood reading list, Roosevelt wasn’t done yet. From his Autobiography:

At the cost of being deemed effeminate, I will add that I greatly liked the girls’ stories—Pussy Willow and A Summer in Leslie Goldthwaite’s Life, just as I worshipped Little Men and Little Women and An Old-Fashioned Girl.

The Greats

The fifty-one-volume Harvard Classics, compiled by Harvard University president Charles W. Eliot, purported to offer all the education you’d need in a collection that could fit on a five-foot shelf. Given his opinions on book recommendations, it is perhaps unsurprising that Roosevelt had thoughts on this collection, which, per the times, included no works by women (not that this concerned him). He responded to the Classics from Khartoum in 1910, beginning with the requisite ego massaging:

Let me repeat that Mr. Eliot’s list is a good list, and that my protest is merely against the beliefs that it is possible to make any list of the kind which shall be more than a list as good as many scores or many hundreds of others. Aside from personal taste, we must take into account national tastes and the general change in taste from century to century. There are four books so preeminent—the Bible, Shakespeare, Homer, and Dante—that I supposed there would be a general consensus of opinion among the cultivated men of all nationalities in putting them foremost; but as soon as this narrow limit was passed there would be the widest divergence of choice, according to the individuality of the man making the choice, to the country in which he dwelt, and the century in which he lived…We are apt to speak of the judgment of “posterity” as final; but “posterity is no single entity, and the “posterity” of one age has no necessary sympathy with the judgments of the “posterity” that preceded it by a few centuries.

“With such an example before us,” he concluded, “let us be modest about dogmatizing overmuch.”

The ingenuity exercised in choosing the “Hundred Best Books” is all right if accepted as a mere amusement, giving something of the pleasure derived from a missing-word puzzle. But it does not mean much more. There are very many thousands of good books; some of them meet one man’s needs, some another’s; and any list of such books should simply be accepted as meeting a given individual’s needs under given conditions of time and surroundings.

For a look at other posterities and personal tastes, see the other entries in our reading list series: Julia Ward Howe, Walt Whitman, Willa Cather, Virginia Woolf, Frederick Douglass, Sylvia Plath, Nella Larsen, Flannery O’Connor, and Emily Dickinson.

And for more of Theodore Roosevelt’s thoughts on books, here is a pamphlet compiled by the Syracuse Public Library in 1920, which collects much of his writing about the books he read.

1 “The books are everywhere,” Roosevelt wrote of home in his Autobiography. “There are as many in the north room and in the parlor—is drawing room a more appropriate name than parlor?—as in the library; the gun room at the top of the house, which incidentally has the loveliest view of all, contains more books than any of the other rooms; and they are particularly delightful books to browse among, just because they have not much relevance to one another, this being one of the reasons why they are relegated to their present abode. But the books have overflowed into all the other rooms too.” ↩