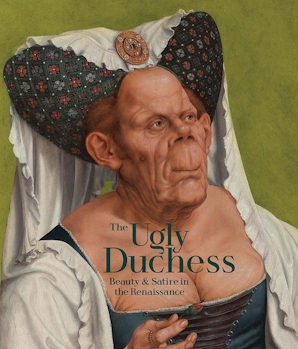

An Old Woman (“The Ugly Duchess”), by Quinten Massys, c. 1513. © The National Gallery, London.

It is always difficult to describe a myth; it does not lend itself to being grasped or defined…It undulates so much and is so contradictory that one cannot at first discern its unity: Delilah and Judith, Aspasia and Lucretia, Pandora and Athena, woman is at once Eve and the Virgin Mary. She is an idol, a servant, the source of life, a power from darkness; she is the elementary silence of truth, she is artifice, gossip, and lies; she is the healer and the witch; she is man’s prey, she is his downfall, she is everything he is not and wants to have, his negation and his raison d’être.

—Simone de Beauvoir, The Second Sex

Renaissance women were bound by an iconographic straitjacket. Either saints or sinners, virgins or courtesans, maidens or hags, beauties or beasts, their depictions broadly reflected the simplistic dichotomy captured by Simone de Beauvoir centuries later when defining the feminine mystique. Primarily commissioned to mark early milestones such as betrothal and childbirth, female portraits painted in the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries tended to celebrate the bloom of youth. They might feature mature women, but rarely elderly ones. In religious images, the Virgin’s mother Saint Anne—the embodiment of matronly virtue—was never shown decrepit. Older women were seldom lent great individuality and psychological depth in the visual arts of the period. Instead, they tended to provide a physical and moral foil to the ideals of beauty, youth, and propriety expected of their gender.

While male old age might at times be mocked, it was also often portrayed as venerable, from the wisdom of philosophers to the dignity of holy men. By contrast, older women generally populated the realm of comic imagery. Meticulously recorded by painters, sculptors, and printmakers, female decay in turn elicited laughter, crystallised anxieties about the passing of time and reflected fantasies over the evil nature of women. Old women also acted as vehicles for social subversion in the visual arts, their unruly bodies becoming a metaphor for moral and political disorder. The period’s increased interest in verisimilitude further made hags attractive subjects for artists, the careful indexing of wrinkles and sagging flesh becoming an opportunity for displays of virtuosity as well as invention: as famously noted by Umberto Eco, while beauty is always constrained by strict norms, the possibilities offered by ugliness—and the shapes it can take—are infinite and unpredictable, thereby affording artists a space for play and experimentation. Binding all those threads together is Quinten Massys’ An Old Woman (“The Ugly Duchess”). As one of the most extraordinary examples of this imagery, it offers a springboard to explore the mixture of pity, fascination, repulsion, and transgression that presided over the representation of female old age during the Renaissance.

In the early modern period, social realities, misconceptions surrounding physiology, and a misogynistic tradition going back to classical literature consorted to shape the view that women not only reached old age earlier than men but also underwent more detrimental effects. By thirty-five or forty a woman was considered to be entering the winter of her life. This is partly because women went through major life stages before men: they tended to marry younger—a step that effectively cut short their childhood—and were usually widowed at a younger age too, sometimes obtaining financial security in the process. Although paradigms of virtuous widowhood existed (primarily embodied by female rulers), in popular culture the material independence of widows, combined with their sexual experience and potential licence, did not fail to make social commentators nervous. Unforgettable literary characters, such as the confident, assertive, and cunning five-times-married Wife of Bath in Geoffrey Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, play on the period’s unease with experienced women. More frequently, older women were impoverished and socially marginalised, and their teaching of girls, who in place of formal education would often turn to them, was seen as a corrupting influence.

Medical treatises fanned these fears through alarming interpretations of the post-menopausal condition. According to Hippocratic, Aristotelian, and Galenian models, women were already undermined by the pre-dominance of colder and moister humours in their physiology (in contrast to men’s dry and hot constitutions). This presumably accounted for their weaker, shiftier character and their greater propensity to sin. The absence of purgation through menses was believed to make matters worse by creating an unhealthy accumulation of nefarious humours. In this view, the old woman’s body was fundamentally polluted, harbouring all kinds of evil, beginning with unbridled lust, the vice most commonly associated with crones. As a result, the sexual insatiability of older women—deemed all the more unnatural by the absence of procreation—became a pervading theme in early modern vernacular literature and prints, from the flirtatious hags of unequal couples to aged procuresses who long to partake in the lovemaking they enable.

Within this rich strand of secular writings and imagery, Massys’ An Old Woman stands out as one of the earliest and most ambitious depictions of unapologetic female desire in European panel painting. The old woman takes the initiative in presenting her prospective mate, An Old Man, with a rosebud as a love token. Her boldness breaks with a visual tradition that glorified women’s virtuous (and mostly helpless) refusal of sex—as testified by the countless illustrations of mythological rapes that became the pinnacle of history painting during the Renaissance, perhaps most emblematically with Titian’s poesie. In contrast to those graceful flights, the old woman’s desire—indecorous, inappropriate, outrageous, out of place—is ridiculed and made ugly. In order to meet her depraved ends, she further attempts to disguise her age through showy garments and coiffure. This deceptive endeavour that runs against the laws of nature likens her to a monster, recalling ancient vituperations against the use of cosmetics by older women. In this, Massys’ figure anticipates a long visual tradition satirizing women who fight against time, from Bernardo Strozzi’s c. 1615 Old Woman at the Mirror to c. 1808 Francisco de Goya’s Time and the Old Women.

Although lust during the Renaissance was usually personified as an alluring, nude young woman, the connection Massys established in his panel between physical decline and untempered sexuality was not coincidental. Contemporary doctors and humanists saw lust and ageing as intimately connected, with the former believed to hasten the latter. This is made plain by Massys’ eminent patron Erasmus in a passage from the Enchiridion (The Handbook of a Christian Knight), an influential manual charting the course of a virtuous Christian life: “[excess libido] simultaneously destroys the body’s strength and beauty, seriously damages its health, engenders innumerable diseases, and hideous ones at that, prematurely disfigures the bloom of youth, hastens a shameful old age.” The old woman’s wasted appearance would therefore have been seen by contemporary viewers not as the mere consequence of time, but as the direct result of her lechery.

In addition to her age, Renaissance viewers might also have understood her exaggerated features as a reflection of her promiscuity. Although the legacy of Aristotelian physiognomy—the pseudoscience that claimed an ability to decipher one’s character through one’s features—was far from taken wholesale in the late Middle Ages and early modern period, facial difference might often be understood as the consequence of sexual transgression: congenital deformities affecting the face were sometimes thought to reveal that a child was conceived outside the bounds of marriage, while female disfigurement caused by illness was usually interpreted as punishment for sexual sins, especially when venereal diseases such as syphilis took hold in Europe in the early sixteenth century. The condition frequently left harrowing lesions on the face, while noxious treatments involving mercury could lead to a collapse of the nose resulting in a short triangular shape not entirely unlike that of An Old Woman. This by no means implies that Massys portrayed someone with syphilis or any other specific medical condition. Rather, it provides a cultural background against which such a grotesque face would have been understood, one in which non-normative features, especially women’s, could function as signifiers for subversive sexual behaviour. This association was to have a surprisingly lasting afterlife: disfigurement through smallpox spelled moral retribution for promiscuous literary heroines as late as the nineteenth century, as witnessed in the spectacular downfalls of the scheming libertine Marquise de Merteuil in Pierre Choderlos de Laclos’ 1782 novel Les Liaisons dangereuses and Emile Zola’s iconic Second Empire courtesan Nana in the eponymous 1880 novel.

Although they were the butt of endless Renaissance jokes, old women were also depicted as powerful, fearsome entities. One of the most iconic such representations is no doubt Albrecht Dürer’s engraving A Witch Riding Backwards on a Goat, its small size belying its visual impact and legacy. As the earliest recorded depiction of a witch as a naked hag, it marks a fundamental step in the demonization of older women in Renaissance imagery.

Dürer’s print does not document the actual horrors of the witch craze, which took off decades later, costing innumerable lives, especially those of older women living on the margins of society. Instead, the image’s complex iconography reflects Dürer’s humanist interest in classical enchantresses as well as the deeply misogynistic views expounded in the influential demonological treatise the Malleus Maleficarum, published in Strasbourg in 1487. In the fantasies of the two celibate clerics who penned it, Heinrich Kramer and Jacob Sprenger, witches were powerful, debauched women intent on controlling male sexuality through black magic. Harnessing traditional associations of old women with depravity, Dürer’s depiction is replete with sexual overtones. With a phallic broom and spindle tucked between her legs, she rides a goat (a creature associated with lust) and suggestively grasps the animal’s horn. Symbolic of the upended gender and moral hierarchies embodied by the witch, inversion reigns supreme in the print: she rides her lascivious animal backwards, her long hair flows in the opposite direction from the goat’s, the putto at lower left bends upside down and even Dürer’s famous monogram is reversed—perhaps a clever nod to the printing process itself and its mirroring of the engraved plate.

The theme of the topsy-turvy world, epitomized by the rule of women over men, was central to Renaissance visual, literary and festival cultures. It is also a fundamental rhetorical device of Massys’ An Old Woman—from her unwomanly sexual overtures to her occupying the more elevated right side, the usual preserve of men in double portraits. This, ultimately, is where Dürer’s witch meets The Ugly Duchess: they both stand as potent incarnations of social disorder, flouting conventions, confronting viewers with excessive bodies that refuse to conform, that will neither be removed from sight nor contained. Although anthropologists have argued that ritual inversions ultimately tend to reinforce rather than undermine social order, there is an undeniable cathartic joy in beholding those difficult, disobedient women: they offered a proxy through which spectators could vicariously partake in transgressive behaviour. In that sense, viewers past and present undoubtedly laugh at these women, but also with them, at the societal norms and beauty standards they so gleefully dismantle. Their ugliness further liberated artists from the narrow confines of decorum, allowing them boundless creative license. In this freedom and irreverence perhaps lies one explanation for An Old Woman’s extraordinarily enduring appeal.

Excerpted from The Ugly Duchess: Beauty & Satire in the Renaissance by Emma Capron and contributors, published by National Gallery Global, distributed by Yale University Press. Copyright © 2023 National Gallery Global. Reprinted by permission of National Gallery Global.