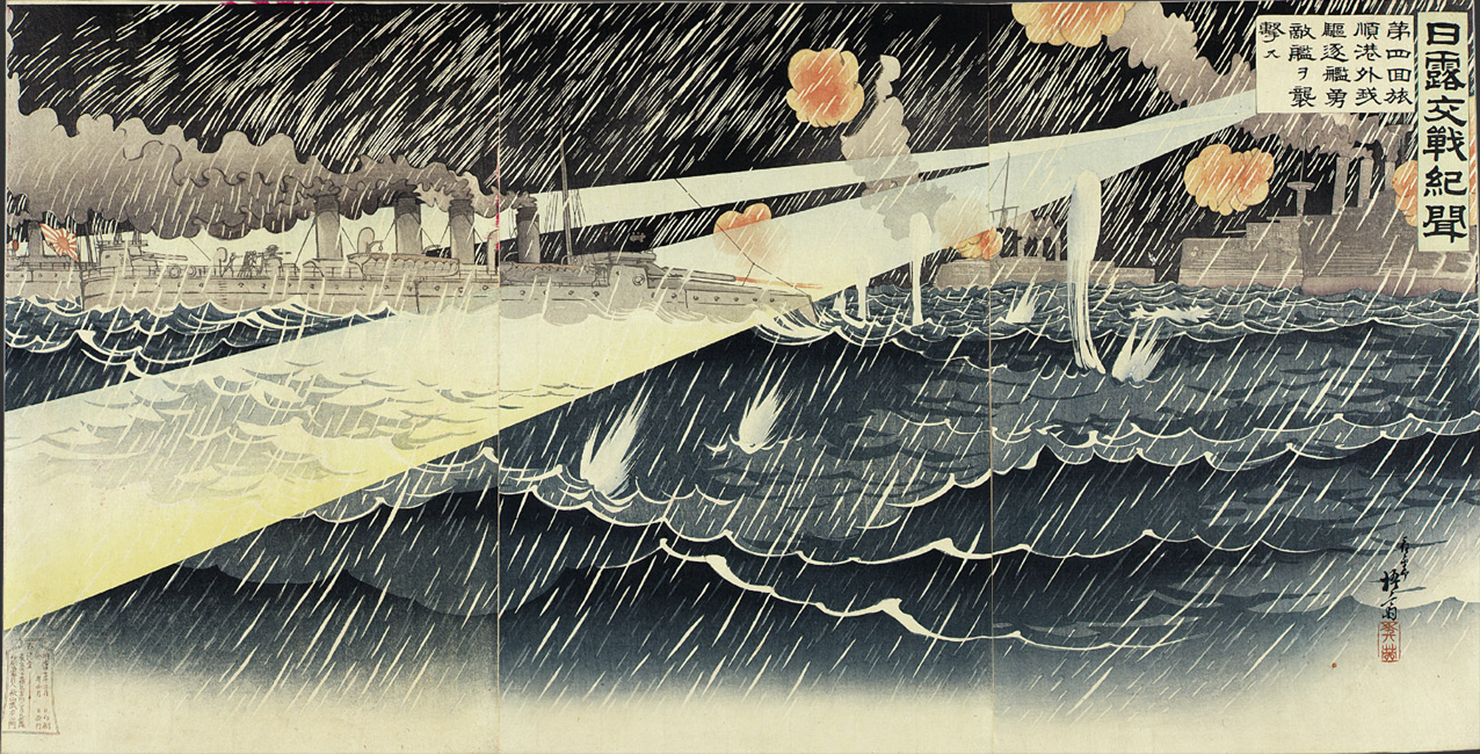

News of Russo-Japanese Battles: For the Fourth Time Our Destroyers Bravely Attack Enemy Ships Outside the Harbor of Port Arthur, by Migita Toshihide, March 1904. Ukiyo-e print from the Sharf Collection, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

To get to Port Arthur—the city at the center of the 1904–1905 war between Russia and Japan and on the peninsula that juts into the Yellow Sea between Tianjin and Korea—I had to take a night train to Dalian, a large city on the Liaotung Peninsula, which in the past hundred years has been fought over as much as Flanders fields or the heights of Jerusalem.

Although I had no trouble getting to Dalian and checking into the Bohai Pearl Hotel near the station, I ran into problems trying to arrange a tour to the battlefields of the 1904 Russo-Japanese War. Not only was it the holiday week around the anniversary of the Chinese Communist Revolution of 1949, but Port Arthur, now called Lushun, is a “closed” city, because its downtown waterfront is a naval base. I knew this from the guidebooks and had written to a number of local tour companies to line up a travel permit and a guide. The answers had been negative, leaving me, upon arrival, to arrange a car from the sidewalk outside the hotel.

I wondered how the freelance driver would deal with Lushun’s closed-city status, as clearly I was a foreigner and had no permit to go there. (The guidebook states: “When you cross the tracks, you have gone too far.” By the time I read that, we were already on the wrong side of the tracks.) Most of the battlefields are outside the city, where no permits are needed. To reach them, the cabbie drove right through the downtown, with me ever so slightly leaning down in the backseat, as if I were in high school and trying to avoid an ex-girlfriend.

We drove past the naval station, with its many ships tied up to the town wharf, and through the business district, which echoes historic associations with Tokyo. A book I had bought earlier that day shows the influence of Japanese architecture in Port Arthur, which was in the Japanese sphere of influence from 1905 until the end of World War II. The railroad station, one of the end points of the Trans-Siberian Railway, has distinctly Russian architecture, however, as the czars laid the lines that stretched across Siberia to Port Arthur’s lukewarm water. On those tracks are the origins of many wars.

Having won the 1895 conflict against China, Japan had lost the peace to the Russians, who ended up with Japan’s spoils of war. To regain what it had lost at the bargaining tables, Japan launched its war against Russia, which it won, in 1904. To find the terminus of these disputes, I had come to Port Arthur.

In the hills above Lushun sits 203 Meter Hill, which overlooks Port Arthur from a distance of about four miles away from the “closed” city. In many respects Russia can lay its 1905 and later revolutions to the events that took place on this hillside. The taxi parked near some souvenir shops at the base of the hill. I walked the last several hundred yards to a saddleback ridge, which connects the two small peaks that together are known as 203 Meter Hill. A few other tourists were lingering at the top and taking pictures of the harbor in the distance. Nearby was a long artillery shell, pointed to the sky, that the Japanese had erected to commemorate their victory here in 1904–1905.

The Russian army had dug into the hillside to protect itself from a Japanese assault, as any artillery, placed on the summit, would control the strategic harbor below. Having marched troops south from the Yalu River, the Japanese army threw wave after wave of infantry up the steep hill, on the side away from the harbor. Despite suffering eight thousand casualties, the Japanese took the summit. The next day on the hilltop, after recommissioning abandoned Russian artillery, the Japanese army sank the remainder of the Russian fleet moored at Port Arthur. At that moment, Russia ceased to be a Pacific power.

The Russo-Japanese War has been called World War Zero because it echoes the kind of warfare seen later in the two world wars. Both sides deployed industrial armies across broad fronts, dug trenches, engaged battleships, and suffered horrendous casualties.

The Japanese fleet attacked the Russians in 1904 because Japan remained furious that its 1895 victory over the Chinese had ended with the Russians controlling Port Arthur and the surrounding Manchurian peninsula. Not only was the Russian presence an affront to the Japanese army, but the government in Tokyo feared that the Russians would move on the Japanese sphere of influence on the Korean peninsula. To attack Port Arthur was to protect its flank.

Moving out silently from the Korean port of Inchon, the Japanese caught the Russian Pacific fleet at anchorage in Port Arthur. Although some ships survived, and others ran from the harbor, enough were sunk for the Russian czar to commit the bulk of his European army to the eastern front, which at first was drawn along the Yalu River, which now separates China from North Korea. There, where the Great Wall begins, the Japanese army outflanked and outmaneuvered the entrenched Russian army and turned south across the Liaotung Peninsula to attack Port Arthur from the land side. Once the Japanese were across the Yalu River, they had Port Arthur surrounded.

Below the summit of 203 Meter Hill, I walked on some paths that cut through the Russian trenches that were dug to keep the Japanese off the summit. They could well have been surrounding Ypres, that site of deadly World War I fighting. In Rising Sun and Tumbling Bear, a history of the Russo-Japanese War, Richard Connaughton describes the carnage that ensued when Japanese banzai attacks were thrown against the Russian entrenchments: “The Russian machine guns scythed through the ranks while the attackers on the granite slopes built parapets out of their dead and wounded…Rarely had the world seen such a concentration of slaughter over such a small area.”

In about half an hour, I covered the area of the fighting, which reminded me of some of the knolls on Okinawa, such as Sugar Loaf, which claimed the lives of so many Marines in my father’s Marine Corps company. The ravines below the summit were rocky, steep, and, once the vegetation was blasted away, afforded little cover.

In Soldiers of the Sun: The Rise and Fall of the Imperial Japanese Army, Merion and Susie Harries write at length about the land fighting of the Russo-Japanese encounter: “The war that was to follow was, in the phrase of one contemporary observer, ‘an encounter between such tactics as were employed by Agamemnon at Troy and those that might have been conceived by [Helmuth] Moltke.’ The Japanese forces, near a peak of potency in 1894, were confronting an enemy in stagnant decay.” The Harrieses quote from the London Times: “The story of the siege of Port Arthur is the story of a succession of Charges of the Light Brigade, made on foot by the same men over and over again, with the scientific destructiveness of modern weapons thrown into the scale.”

Walking through the woods on the reverse slope of the hill, I came across a marker pointing me to “A Place Where Kitten Naikito Be Killed.” It was a reference to the Japanese commander’s son, who was killed in the frontal assaults on the Russian trenches. I was alone in the woods, thinking about the battle, when a young Chinese man approached the monument in the woods. He was well dressed and had a camera around his neck but was obviously in a hurry. He paused a bit when he saw me, but then drew himself up and spat at the marker.

From 203 Meter Hill, I had the driver search for Dongjuichan, the remains of a Russian fortress that anchored another part of the perimeter in the Russian defense of Port Arthur. The driver wasn’t keen to find it and only halfheartedly asked some residents where it might be. Finally he drove up a dirt lane. There we found a fortress as daunting as anything along World War I’s Western Front—except that it had barely held out against the Japanese attacks, given that supplies could not reach the Russian garrison from either land or sea.

Reminded of the French battlefields of Verdun, I walked around the entrenchments. The fortress had been built with coolie labor and was intended to protect Port Arthur from the Chinese hordes, not a mobile Japanese army, which took the fort after a brief siege, about the time that 203 Meter Hill fell. Reflecting on the battles, the Harrieses conclude: “In the natural amphitheater of Port Arthur, with the world’s press and military observers looking on in fascination, the Japanese soldier was caught up in siege war that looked back to his country’s middle ages and forward to the trenches of World War I.”

Another reason why I came to Port Arthur was to complete a circle that I had begun to draw when I went to Portsmouth, New Hampshire, to visit the museum that is dedicated to the peace treaty ending the Russo-Japanese War. The treaty was negotiated in and around the small New England coastal city, and a group of local residents has kept alive the diplomatic triumph, for which President Theodore Roosevelt won the Nobel Peace Prize. Playing the role of “honest broker,” he summoned delegates from Russia and Japan to the United States; greeted them at his home in Oyster Bay, New York; and then dispatched them to Portsmouth to work out a settlement to the terrible war.

The Portsmouth Peace Treaty Forum publishes monographs on the negotiations, issues commemorative coins, holds seminars and lectures, gives out a prize, and distributes a map so that tourists can make their way around the contours of the settlement. When I was in Portsmouth, I met with the president of the Forum, Charles Doleac, whose law office was crammed with artifacts, paintings, murals, and maps, all showing aspects of the Russo-Japanese War.

In his New Hampshire office, Doleac tells a compelling story of an American diplomatic triumph, which ended fighting that had become as gruesome as the Napoleonic wars and on a similar scale. First, Roosevelt had to convince the warring parties that the United States could broker the peace. At the time, the United States was a Pacific power, although it had confined its imperial ambitions to the Philippines, taken from Spain in the 1898 Spanish-American War, and to fighting in the Boxer Rebellion.

In summer 1905, the United States and President Roosevelt were convincing in claiming to be neutral in the fighting between Russia and Japan. By contrast, the other European powers had conflicts of interest: France was an ally of the Russians, and the German kaiser was related to the czar. (Wilhelm had encouraged his cousin Nicky—Tsar Nicholas II—to go to war with Japan, which he regarded as a savage nation.) Britain was an ally of the Japanese and had trained the navy that had sunk the Russian fleet in the Strait of Tsushima. When Roosevelt extended the olive branch, the Russians and the Japanese agreed to the talks, provided that they were “direct” between the combatants and that Roosevelt personally stayed away from the negotiating table.

Portsmouth was chosen for the peace talks because a delegation from the local tourist industry had gone to Washington to promote the hotel infrastructure of nearby Lake Winnipesaukee. But Roosevelt wanted the U.S. Navy involved with the protocol and moved the site of the peace conference to the coastal city, which also had a number of rambling seaside hotels, including the Wentworth, where the delegates stayed and which has become synonymous with the peace treaty. The actual talks were held at the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard (technically across the river in Kittery, Maine) on the Piscataqua River. When Roosevelt greeted the delegates in Oyster Bay, he urged them to skip deal-breaking points and to resolve all other issues.

True to his word, Roosevelt did not attend the talks for which he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, though he was kept informed of the discussions and the points outstanding. Through political and Harvard connections, Roosevelt had back-channel links to the Russian tsar and the Japanese cabinet. He used this “multi-track diplomacy” to push the Japanese and the Russians toward a resolution of the conflict. Roosevelt found willing negotiating partners in Japan, because the army had taken the land that it sought, and in Russia, which had lost its Baltic fleet and was in a state of revolution. It did not hurt his chances that the spoils of war under negotiation belonged not to Russia or Japan but were Chinese and Korean. In his history of the Trans-Siberian, Harmon Tupper writes: “The Russo-Japanese War resulted from the competition of two nations for mastery over alien territories to which neither had the slightest shred of legal or moral right.”

In fairly short order, the negotiating parties in Portsmouth had agreed to a number of peace-treaty terms. Japan would control the Korean peninsula and acquire the Russian leases to Port Arthur and the South Manchuria Railway. Both the Russians and the Japanese agreed that the rest of Manchuria would be returned to the Chinese. Where the negotiations faltered was on the subject of Sakhalin Island, which the Japanese wanted, and over an indemnity, which Japan thought it was owed by the Russians, as the losing party in the war. Indemnities were routinely paid after European wars, but Russia refused to pay one.

Roosevelt’s back-channel diplomacy persuaded the Russians to give up half of Sakhalin, along with the Kurile Islands, to the Japanese, and he persuaded the Japanese to drop the demand for an indemnity. According to Doleac, he made the point to the Japanese that it would look ruthless to continue fighting a war for the sake of money. Nevertheless, there were many moments during the summer talks by the sea when the negotiations could have ended. Several times the Russian tsar recalled his lead negotiator, Sergius Witte, who gently ignored the orders and stayed at the table. He knew that the tsar needed peace to deal with the growing revolution, and he was certain that Russia would go bankrupt before it drove the Japanese out of Manchuria. He was fortunate to find that his Japanese counterparts were also short on the money needed to continue fighting and that English bankers had turned off the flow of funds to Japan.

What no one knew when the improbable peace was announced—to world acclaim for Roosevelt and the United States, not to mention the hotel industry in Portsmouth—is that the peace treaty burned a generation of resentment into the Chinese, Japanese, and the Russians, all of whom spent the next fifty years trying to reverse the terms of the settlement.

A glimpse of Chinese anger at the Portsmouth Peace Treaty can be found in the small Dongjuichan Museum, which has a large relief model of Port Arthur; numerous pictures of the Russian tsar sending off his Baltic fleet; and many storyboards, translated into English, that denounce the “Ports Mouth Share Booty Peace Treaty.” The museum sums up the 1895 Sino-Japanese War as follows: “Lushunkou has important strategic position. Is a place contested by all strategists. It was invaded and occupied by Japanese army interfered on ‘Return Liaodong Peninsula,’ it was again invaded and occupied as naval base by tsarist Russia.” Another storyboard reads: “After Russian army was defeated and surrendered, ‘Ports Mouth Share Booty Peace Treaty’ was signed by and between Japan and Russia under the control of America. Lushun became the colony of Japan again and was ruled for 40 years long.” The English may be fractured, but the messages are clear.

On the lessons of the Russo-Japanese War, the museum captions conclude: “The age when Chinese people were partitioned by others at will has gone away forever. But we will remember the bitter lessons of lagging behind and being vulnerable to attacks in the past nearly one hundred year generation after generation. To rest invasion, make country strong and to invigorate the Chinese national are the aspiration of all Chinese people.” Clearly, the Chinese were not among those voting for Roosevelt’s Nobel Prize.

Equally, Russia burned with indignation about its military defeats in the Far East. Not only were the failures of the Russian army and navy laid to the tsar, but the country literally and metaphorically went broke as the Japanese were battering against the defenses around Mukden. Although Russia could have kept the war going by retreating to Harbin and summoning more men and matériel from the West, Nicholas II’s government had lost its fleet, some of its best divisions, the South Manchuria Railway, Port Arthur’s warm water, and its standing as an effective political force. Only repression and a world war kept the tsar on the throne for another twelve years after the 1905 revolution.

Even the subsequent Soviet government in Russia burned with resentment over the terms of the Russo-Japanese War—so much so that at Yalta, in February 1945, much of the agreement that Stalin negotiated dealt with issues first covered in Portsmouth. Nor did Japan easily accept the terms of the Portsmouth peace treaty. The Imperial Japanese Army had won what it set out to conquer, and the cabinet knew that the government, without support from Britain, was running out of money. But the Portsmouth treaty continued a string of postwar diplomatic defeats that weakened the government at the expense of army-dominated parties, which felt that they had been cheated of full victory.

This pattern continued in World War I, in which Japan sided with the Allies, in the hope that, yet again, it would be recognized as a player in the partition of China. For its alliance Japan had hoped to take over the German concessions on the Shandong peninsula (Tsingtao, where the beer is brewed) and its Pacific island colonies. Japan got only half of what it wanted, despite earlier Allied assurances, and walked out of the Paris Peace Conference, much as it would later depart in a huff from the League of Nations. In these examples, Japan learned not to trust Western negotiators. Not only was the attack on Pearl Harbor a rerun of the tactics used at Port Arthur, but it was also a clumsy attempt to redress the grievances that had built up since the Peace of Portsmouth. Some of the depth of Japanese resentment can be gleaned from the fact that the Japanese fleet that attacked Pearl Harbor flew the same pennants that had earlier flown from the ships that attacked Port Arthur.

Adapted from Reading the Rails by Matthew Stevenson, published by Odysseus Books. Copyright © 2016 by Matthew Mills Stevenson. All rights reserved.