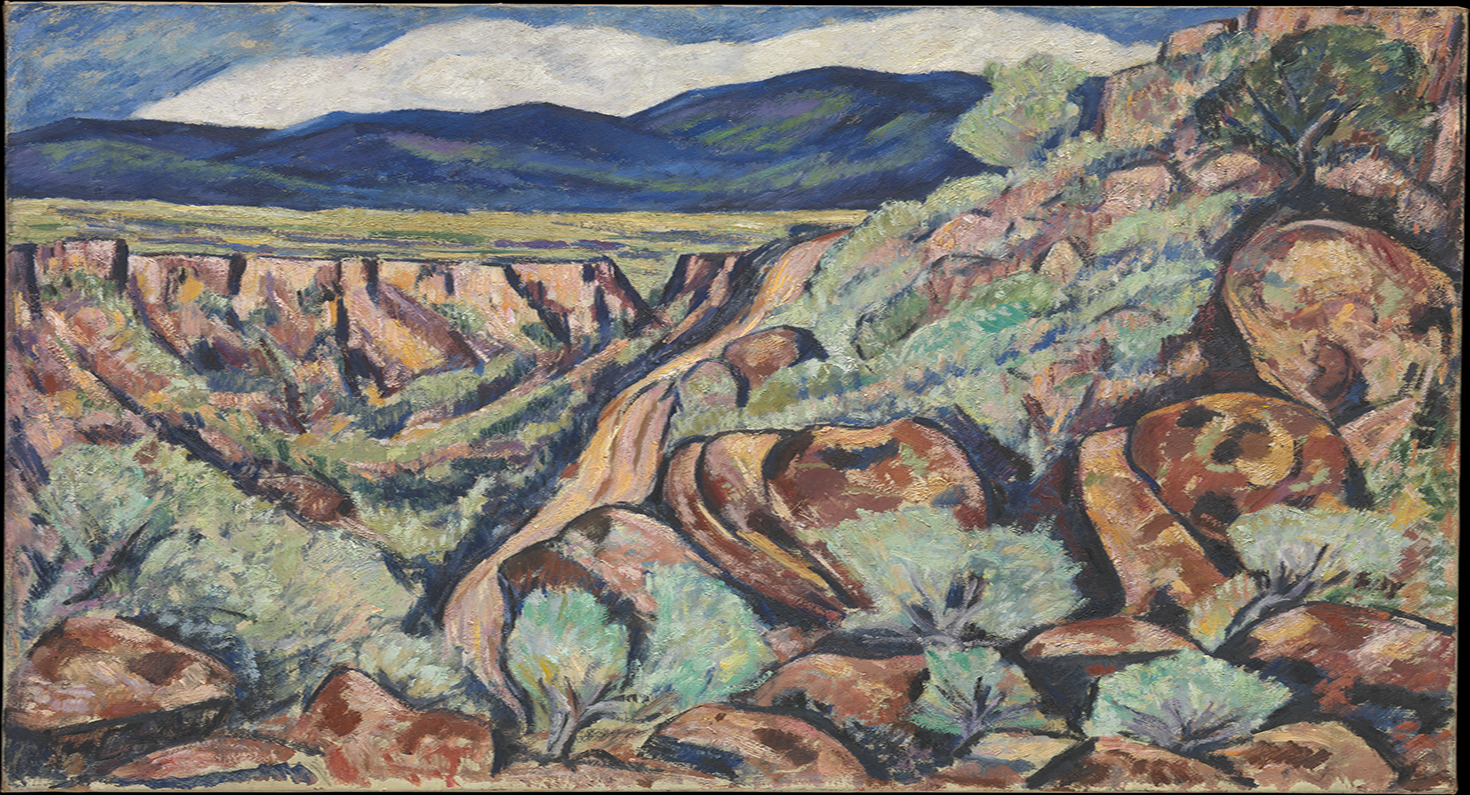

Landscape, New Mexico, by Marsden Hartley, c. 1919. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Alfred Stieglitz Collection, 1949.

In 1884 Charles Fletcher Lummis, a relatively unknown journalist from Ohio, began a correspondence with the editor of a “breezy” Western newspaper that had sprung up in deserts of southern California. It was called the Los Angeles Daily Times. Lummis was looking for a new job, and after sending a few letters to the editor, Harrison Gray Otis, he had the nerve to ask him for one. Otis liked the young man’s writing, so he offered Lummis a position—and a train ticket out west. Lummis had other ideas about how to get to Los Angeles. He didn’t want to go by train. That would be “tedious.” He decided, instead, that he would walk.

After making his 3,500-mile journey, a “tramp” that took him 143 days to complete, Charles Lummis went on to become one of the most important proponents and chroniclers of the life and culture of the American Southwest. His vision of the region as a land of natural and cultural enchantment endures today. As a writer of sixteen books, a poet, photographer, magazine editor, Indian rights activist, amateur architect, librarian, and champion of artists and ethnologists like Frederic Remington and Adolph Bandelier, he gave new meaning to that tired phrase about working tirelessly. Despite his output, Lummis himself is little remembered by history, in part because his vision of the Southwest was clouded by a myth of his own making.

Lummis was born in Massachusetts in 1859. His father, a Methodist clergyman, gave him a strict, old-fashioned education. He was “well drilled in the common branches,” having learned Latin at the age of seven, Hebrew at eight, Greek at ten. Despite the academic drills, or perhaps out of rebellion, Lummis didn’t do well at Harvard. Sometimes, instead of going to class, he walked the railroad tracks outside of town, armed with a pistol, looking for rabbits to shoot.

His first passion was athletics, especially wrestling and boxing. He was small in stature and possessed the kind of pugnacious attitude that made it difficult to keep things inside the ring. “I have always had the ill luck,” he wrote, “to fall into fights and get maimed therein. In a sophomore quarrel I was shot in the left side, the ball glancing a couple of inches from the heart. I have also been stabbed several times, thanks to an exuberant spirit.” Exuberant spirit or not, this passage, like much of Lummis’ writing, is hard to evaluate. The reader is left to wonder what is truthful and what is self-aggrandizing exaggeration. In his memoir, written much later, he claimed to have once run the hundred-yard dash in ten seconds flat. It would have been the world record at the time.

In 1880 Lummis wedded a Boston University medical student named Mary Dorothea Rhodes. Letters suggest that the two of them had been caught in a compromising position, but that does not explain why Lummis kept the marriage a secret from all but his closest family members for the entire first year they were together. Is this early evidence of Lummis’ desire to exert a tight control over his self-image? Whatever the situation, it did not prevent Dorothea’s father from offering Lummis a career as the manager of the Rhodes family farm near Chillicothe, Ohio. What’s surprising is that Lummis accepted it. Did he feel that his hand was forced? He had dropped out of Harvard the year prior. He had done freelance writing and sold a few self-published poems, but as any poet can tell you, that does not hold much promise. In 1881 he moved to Chillicothe to plow those four hundred acres, and it was there on the farm that his plan to tramp out west took root.

Lummis’ A Tramp Across the Continent, published by Charles Scribner’s Sons in 1892, tells the tale of his five-month walk across America: “I was after neither time nor money, but life—not life in the pathetic meaning of the poor health-seeker, for I was perfectly well and a trained athlete; but life in the truer, broader, sweeter sense, the exhilarant joy of living outside the sorry fences of society.” What goes unsaid is that Lummis also wanted to make a name for himself.

Long-distance walking might seem a peculiar method of self-promotion, but that was not the case in nineteenth-century America. Walking could make you famous. During the 1870s and 1880s, long-distance walking, or pedestrianism, was America’s most popular spectator sport. Thousands of fans attended the races held at Madison Square Garden, where the giants of the sport—figures like Edward Payson Weston, the Irishman Dan O’Leary, and O’Leary’s Jamaican-born protégé Frank Hart—walked grueling distances, sometimes more than five hundred miles, in pursuit of glory and prize money. The exploits were not confined solely to walking a track either. In 1867 Edward Payson Weston’s name became “a household word,” according to Harper’s Weekly, when Weston completed a 1,200-mile walk from Portland, Maine, to Chicago. A similar celebrity awaited Lummis. A letter from John Herlihy in Vincennes, Indiana, describes how Lummis’ march to California had aroused the citizens “to an intense pitch of curious excitement.” His arrival “just tore up the burg. Six hundred or more people witnessed his entrance into the town.”

Why such fascination with walking? Anyone can walk. Maybe that was part of the appeal. Anyone could walk, and that was all most people needed anyway—not escape itself but the possibility of escape. For a people more and more bound to the city, more confined to factory work and its bitter hours and cramped spaces, to a people suffocating from the smoke and greed of industrialism, a walk under open skies must have seemed the purest freedom.

In A Tramp Across the Continent Lummis fashioned himself as a man unafraid to cast off the shackles of society and stride westward: “In my pockets were writing material, fishing tackle, matches and tobacco, and a small caliber revolver.” Mundane lists like this do a great job of underscoring exactly what has been left off the list, namely gumption, and there is no greater theater for the display of gumption than the mythic American West. In our country’s imagination, the West has long been a place where men could regain the strength that had been sapped by society. “Life consists in wildness,” wrote Thoreau, in his essay “Walking.” “The most alive is the wildest.”

Lummis drew on that mythology in A Tramp Across the Continent but converted it to a more consumable, popular form. He fought off bandits with his bare hands, won a shooting contest, and survived a wildcat attack. These now read like fixtures of the Western, but at the time the genre was not yet in full form. Owen Wister wouldn’t publish The Virginian for another decade. Lummis relied upon early progenitors like James Fenimore Cooper and Captain Mayne Reid, an Irishman who wrote adventure novels set in the wilderness. In doing so, Lummis added another tie to the track that leads away from the historical West and toward the Western. But unlike the works of Cooper or Reid, which tell of fictional characters, Lummis fashioned himself as the hero.

In New Mexico, Lummis did a curious thing: he made a costume change. He began his walk dressed in knickerbockers—certainly not a Western look. One man mistook him for a baseball player. By Santa Fe, he had replaced the knickerbockers with “a handsome pair of buckskin leggings, made for some Apache dude.” Ostensibly, the buckskin did a better job of keeping out the cold, but his loving description of the garment, “as soft as velvet, as white as kid,” speaks of its deeper symbolic importance. Most tellingly, he wrote that the pants “fit like his own hide.” He was transitioning into a Westerner.

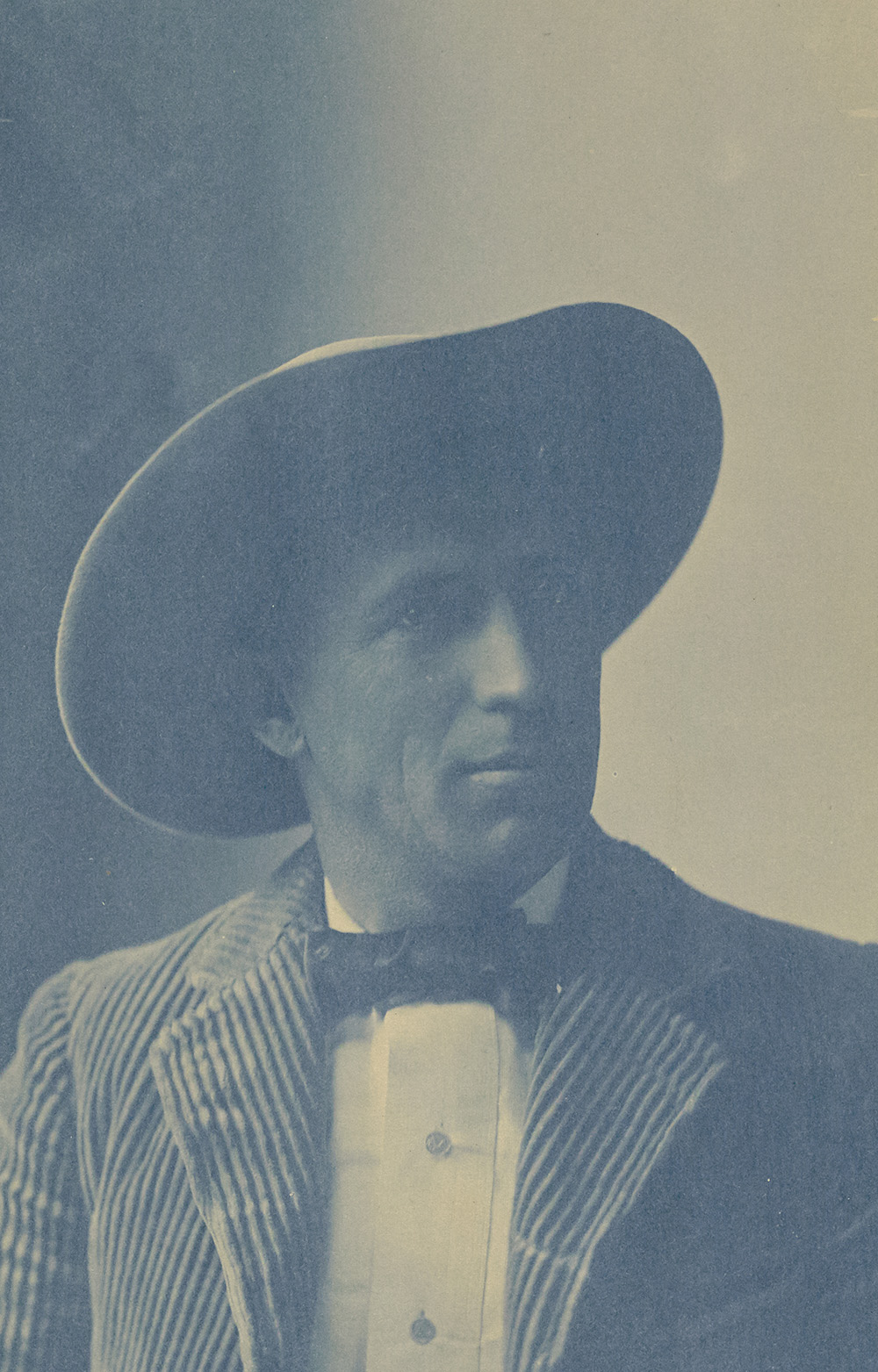

At what point does the persona overtake the person, or to put it in Lummis’ terms, when does the buckskin suit begin to fit like your own hide? A photo of Lummis taken in the 1890s, well after his arrival in Los Angeles, is the model for the original cover of A Tramp Across the Continent. It shows Lummis in full Western regalia, with wide-brimmed hat, leather chaps, a revolver on his belt, and a serape slung over his shoulder. It’s a promotional photograph, but it’s not the only artifact to suggest that the space between self and self-promoting myth had collapsed. He had taken to calling himself Don Carlos, and he lit his cigarettes with a piece of flint and a rag dusted with gunpowder, like the Spanish vaqueros of old. These might be read simply as personal eccentricities, but they speak of a certain quality of mind. The same romanticism that gave shape to his self-mythologizing clouded many of his other writings about the West.

“Sun, silence, and adobe—that is New Mexico in three words.” In The Land of Poco Tiempo Lummis sells us a vision of the Southwest that would be familiar to any reader of today’s Sunset, the “enchanted light,” the “quaint, terraced architecture of the pueblos.” “Why hurry with the hurrying world?” he wrote. This pastoral landscape, where sheep “doze again on the mesas,” is mostly untouched by “Saxon excrescences.” Lummis was deepening the old myth of the West as an Edenic refuge from the evils of eastern industrialization, but such an escape, like all escapes, comes with its own set of shackles.

In their biography about their father, Keith Lummis and Turbese Lummis-Fiske tell an interesting anecdote from their childhood.

Every night after supper, he would settle down with his guitar to sing with us at El Alisal [the family home in Los Angeles]. But his wistful hope that we too would manifest the Latin miracle of happy-heartedness was never realized. He had forgotten that the Del Valles and the Chaveses sang because they were happy. There we sat like members of chain gang, contributing only a grudging mumble, waiting to be set free.

Lummis published A Tramp Across the Continent nearly a decade after he arrived in Los Angeles, but it is not the only record of his journey. He also wrote two sets of letters from the road. The more sensational and self-promotional letters were published in the Los Angeles Times, where he worked as city editor and reporter until 1887. Those letters are the ones he based the book on. The other set went back home to Chillicothe, Ohio, where they were published in the local paper, the Leader. Lummis typically composed the Ohio letters first, and they represent a more direct, off-the-cuff record of the journey. They provide the reader with a chance to glimpse a more complicated Lummis and a less varnished West.

What’s most notable about the Ohio letters is how political they are. In September 1884, as Lummis was starting his walk, America was in the midst of a presidential election that pitted Republican James Blaine against Democrat Grover Cleveland. One of the more contentious issues was a tariff levied on imported goods. Blaine supported increasing it, believing it would strengthen American business interests. Cleveland wanted reform, arguing that the tariff decreased competition needed to curb the rise of monopolies. In the beginning, Lummis’ preference was clear. He was a New England Republican of the old, abolitionist sort, and he joked that if Americans elected the Democrat he would “light out for the Sandwich Islands, where they don’t wear many clothes, but still have some decency left.” A few months later, after Cleveland did in fact win the election, the self-proclaimed “solid Republican” wrote that the defeat didn’t really “gall” him. What had happened in the meantime?

It is worth pausing here to note Lummis’ frequent use of the word tramp not only in the title of his book but also in his letters. He was not out on a walk or a journey or a “saunter,” as Thoreau might have had it. It was a tramp. During the Civil War and its aftermath, the word tramp had become associated with the growing population of homeless people, a fact that wouldn’t have escaped Lummis. By using that word, he acknowledged that he was out “bumming” it. He had adopted the mode of travel of “the wandering poor,” and as Lummis reflected in a letter from Santa Fe, the mode of travel can make all the difference in what one sees: “I don’t think you really comprehend what 2,202 miles means. It looks pretty well on paper; it is a long and tedious ride by train; but the full magnitude of that distance can never be realized save by those who have measured it off a step at a time.”

By taking it a step at a time, Lummis had the chance to see and speak to the people of the West. He slept in farmhouses, with beds “as hard as husks.” At a ranch in Kansas, he spent an evening singing with “the women, the children, the herders, the cowpunchers, and the farmhands.” He tramped 131 miles with a cowboy who had gambled away “his money, his pistols, and his pony.”

Lummis’ journey exposed him to the harshness of western life and the depredations of unchecked capitalism. In Colorado, he spoke with dozens of farmers forced to pay ruinously high irrigation royalties to the Platte Canal Company: “They are bankrupt and despondent, almost without hope. They have spent their last dollar, many of them, and they do not know where the next is coming from.” This is not the idyllic West that Lummis later portrays. Gone is all the airbrushing. This is a West that big business has by the throat. “The east has her monopolies,” he wrote from New Mexico, “and they are big and dangerous, but they have grown with our growth, and we do not realize their full menace. But out here in this new country of sudden fortunes, monopoly has sprung full-armed from the ground almost in a day.”

It’s difficult to know what caused Lummis to turn away from this more cold-eyed vision of the West. It was less palatable to a broad audience, less saleable, and ultimately Lummis had a product to sell. But his sympathy for his fellow man was real. While still in college, he had dreamed of going abroad to Europe “to see the country and the common people closely.” Instead, he met them in the wilds of America. Once, in southern Colorado, he could not find a warm place to sleep. No one would let him in, not the workers at the railroad section-house or the group of “hoggish” Americans on the construction train. “It was desperately cold,” Lummis wrote, “and I was getting ruffled, when a gang of Italian laborers offered me room in their car.” Lummis’ writing finds its feet in moments like this: a glimpse of a wandering people. It was not only suffering of those people that Lummis’ work hoped to memorialize but also their kindness.