Raphael’s fresco of Psyche and Venus at the Villa Farnesina, c. 1890. Photograph by Domenico Anderson. Rijksmuseum.

This summer, Lapham’s Quarterly is marking the season with readings on the subject or set during its reign. Check in every Friday until Labor Day to read the latest.

Before dawn on September 3, 1786, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe slipped out of the Bohemian spa town of Carlsbad and headed for the Italian border. A few days earlier he had celebrated his thirty-seventh birthday with his patron Charles Augustus, grand duke of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach, and a group of friends in Carlsbad. Goethe usually enjoyed lengthy stays in Carlsbad, believing in the health benefits of its mineral waters, but he did not linger on this trip, leaving town in the early morning to avoid any awkward goodbyes. He had grown weary of the life he had lived for the past decade. Serving as the duke’s political adviser at the court in Weimar was boring. His literary output had suffered, none of his fiscal reforms were implemented, and his only romance was a lengthy platonic affair with Charlotte von Stein, wife of the duke’s equerry.

Desperate to get out of town, Goethe wrote Augustus asking for an indefinite leave of absence:

Forgive me for being rather vague about my travels and absence when I took leave of you; even now I do not quite know what will happen to me.…The baths these two years have done a great deal for my health, and I hope the greatest good for the elasticity of my mind, too, if it can be left to itself for a while to enjoy seeing the wide world.

Goethe traveled throughout Italy for the next two years. He spent the most time in Rome, living with the German painter Johann Heinrich Wilhelm Tischbein. Through Tischbein, Goethe was introduced to a circle of German and Swiss artists, including the painter Angelica Kauffman. Goethe had studied drawing as a young man in Leipzig, and in Rome he practiced sketching the human body, using plaster casts of classical sculptures. He also worked on several unfinished projects, such as the multivolume novel Wilhelm Meister’s Apprenticeship and the tragic plays Egmont and Faust.

He reported on his progress in letters to Charles Augustus, Charlotte, and other friends. He documented nearly every step of his journey for Charlotte, writing letters to remind her of his affection during his absence. Thirty years later he collected these letters alongside contemporaneous diary entries and later reminiscences of Italy in the travelogue Italian Journey. The translation below, by A.J.W. Morrison and Charles Nisbet, comes from an 1892 edition that does not identify the recipients of the letters. W.H. Auden and Elizabeth Mayer, whose joint translation of Italian Journey was published in 1962, suggest Goethe sought through his letters to convince his friends in Weimar that traveling would improve his art: “If the reader sometimes becomes impatient with Goethe’s endless reiterations of how hard he is working, what a lot of good Italy is doing him, he must remember that Goethe is trying to placate his friends for being obviously so radiantly happy without them.”

July 5, 1787

My present life looks entirely like a dream of youth; we will see whether I am destined to enjoy it or to find it, like so much else, only a fleeting illusion. Tischbein is gone, his study put in order, dusted, washed, made pleasant for me to occupy. How needful at this season to have an agreeable rooftree! The heat is intense. I get up at sunrise, walk to the Acqua Acetosa, a chalybeate spring about half an hour’s distance from the gate where I live, and drink the waters, which taste like weak Schwalbach but in this climate are very operative. Toward eight I am again in my house and diligent in all ways the disposition of the time allows. I am right well. The heat drains you off everything dropsical in your system and drives whatever pungency is in your body to the skin, and it is better for a trouble to tickle your surface than gnaw your vitals. In drawing, I go on cultivating taste and hand. I have begun to ply architecture more seriously; everything gets astonishingly easy—as far as the conception is concerned, I mean—for the execution needs a lifetime. What helped me most I brought with me here, no self-conceit, no pretentions, no requisitions. And now all my desire is to have done with name, to have done with word. Whatsoever is deemed beautiful, grand, venerable, I will see and appreciate with my own eyes. The only method by which this is possible is that of reproduction, that of copying the objects under consideration. I must now set myself to the gypsum heads. The right way to this is being indicated to me by artists. I keep the reins of all my powers in hand as well as possible, so as to lose no force through distraction. At the beginning of the week, I could not refuse dining here and there. Now they want to have me at this and that place, but I take no notice and keep still in my retreat.

Egmont is on the anvil, and I trust it will turn out a good job. At any rate, in the making of it I have hitherto all along had monitions in my mind that have not betrayed me. It is very strange to think how I have so often been hindered from concluding the piece, and that it is now to be finished in Rome. The first act is matured and copied out clean, and there are whole scenes in the piece that no longer require touching up.

I have so much occasion to ruminate on all kinds of art that, with the nutriment it receives, my Wilhelm Meister swells to a great size. The things I have been so long meditating and cherishing must now first be finally disposed of to make room for new. I am old enough, and if any more work is to be got out of me, I must have done with dawdling. As you may easily suppose, there are a hundred fresh things buzzing in my head, and the whole difficulty is not thinking but executing. ’Tis a plaguey concern, giving a subject one particular determinate shape it must forever retain. I should now like to say a good deal about art, but without the works of art for mutual reference, how to say anything? I hope to clear away many a little obstacle; don’t therefore grudge me my time I spend here so strangely and wonderfully; indulge me so far through the good opinion of your love.

I must close this time, and against my will send you a blank page. The heat of the day was great, and toward evening I fell asleep.

July 16

It is now far on in the night and you do not notice it, for the street is full of people singing, playing on guitars and violins, shifting places with each other, streaming up and down. The nights are cool and refreshing, the days not intolerably hot.

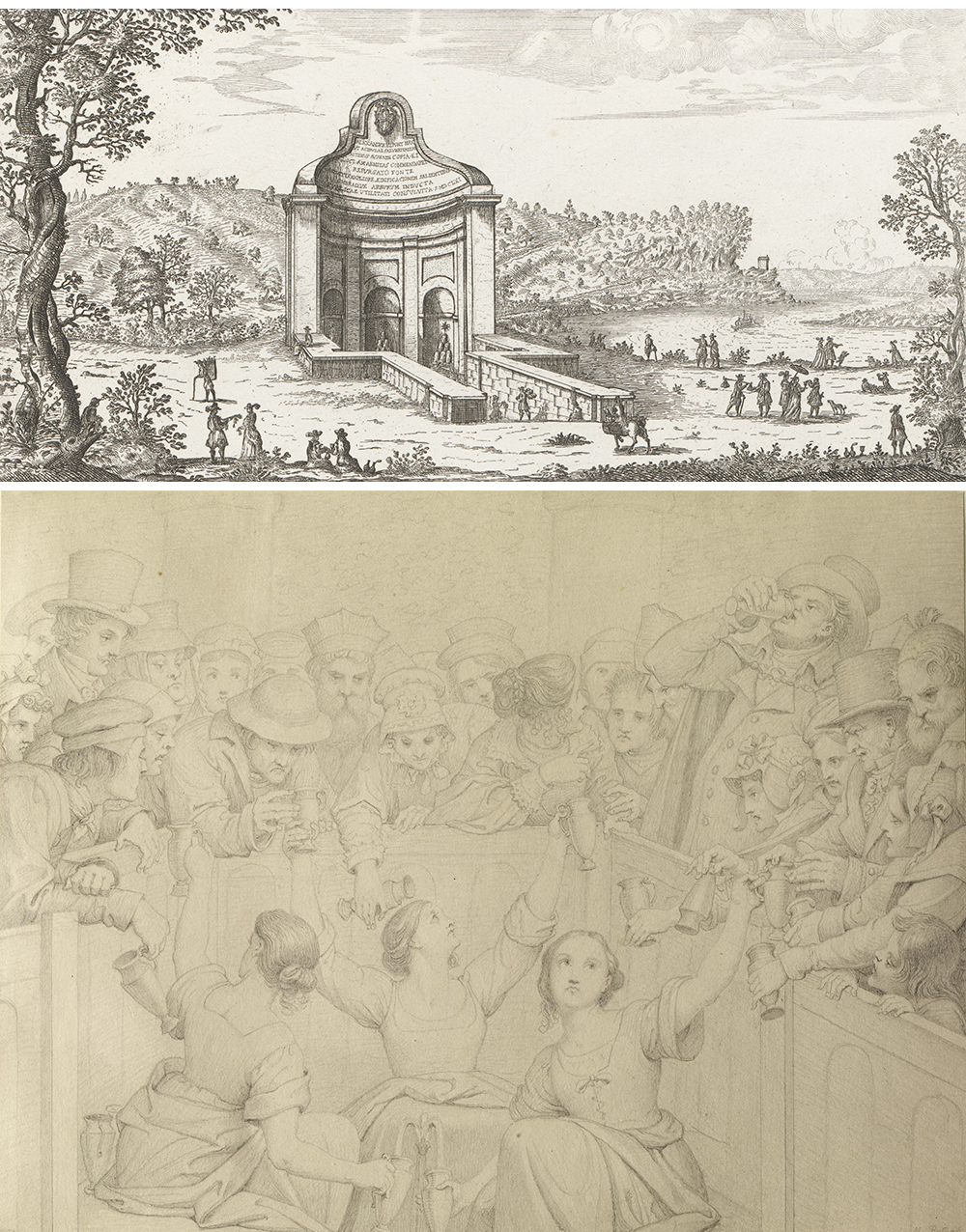

Yesterday I was with Angelica at the Farnesina, where is painted the fable of Psyche. How often, in how many situations, have I contemplated with you the bright copies of these pictures in my rooms! The thought struck me forcibly, knowing as I did from the copies these representations almost by heart. This salon, or rather gallery, is the most beautiful I know in respect of decoration, notwithstanding all the destruction and restoration it has sustained.

Today was beast-baiting in the mausoleum of Augustus. This large building, empty inside, open above and quite round, is now turned into an amphitheater, an arena for bullbaiting. It will hold from four to five thousand persons. The spectacle itself was not very edifying for me.

July 20

Just these days have I found out two of my capital faults, which have dogged and vexed me all my life long. One is that in any business I wanted or ought to undertake, I would never learn the workmanship. Therefore it is that with so much natural talent I have done and accomplished so little. All my achievements have been extorted, happily or unhappily, as fortune and chance determined, by sheer force of mind; or if I would set deliberately to do anything well, I was full of misgivings and would never have done. The other fault, nearly allied to the one just mentioned, is that I would never devote so much time to any work or business as was required. Enjoying the happiness of being able to think and compose a great deal in a short time, a regular progressive execution was irksome, and at last intolerable to me. Now I should think the time was come to correct all this. I am in the land of the arts; let me work my way solidly through the department, so that for the rest of my life I may have peace and joy and be able to proceed to something else.

Rome is a splendid place for this. Not only do you find all kinds of subjects here but also all kinds of men who are in earnest about their different pursuits, setting about them according to right methods, to converse with whom is to advance yourself at once, very conveniently and speedily. Heaven be thanked, I begin to learn and receive from others!

And so I find myself, body and soul, better than ever before! Would you but saw it in my productions and praised my absence! By all I do and think I am united to you. For the rest, I am, to be sure, much alone and must modify my conversations. That, however, is easier here than elsewhere, there being always something interesting to say to everyone.

July 24

Went to the Villa Patrizi to see the sun setting, to enjoy the fresh air, give my mind a good fill of the picture of the great city, widen and simplify my horizon with the help of the long lines and enrich it with so many beautiful and varied objects. This evening I saw the square of Antoninus’ column and the Chigi Palace illumined by the moon, the column, black with age, with a white shining pedestal, under the still more shining sky of night. And what innumerable other objects does one encounter in the course of such a promenade! But how much is required to appropriate only a small part of all this! It requires the life of a man, nay, the lives of many men, learning in progressive stages, each from his predecessor.

July 29

I have been with Angelica in Rondinini Palace. In my first Roman letters you will remember a Medusa that even then clearly discovered its meaning to me but that now gives me the greatest joy. The sense of the existence of such a thing in the world, of the human possibility of such a thing, doubles the value of a man’s life. How gladly would I say something on such a topic were not all words on such a work the inanest breath. Art is for the eye, not for the tongue, except, at least, in immediate presence. How I take shame to myself for all the art gossip I formerly joined in! If I can possibly get a good gypsum cast of this Medusa, I shall bring it with me, but it must be of another kind than those here for sale, which frustrate rather than impart and sustain the idea of the original. The mouth in particular is unspeakably, inimitably great.

Read the other entries in this series: Charles Dudley Warner, I.A.R. Wylie, Jennie Carter, Virginia Woolf, Fyodor Dostoevsky, Willa Cather, Thomas Jefferson, Fridtjof Nansen, Elizabeth Robins Pennell, Izumi Shikibu, Hilda Worthington Smith, Mark Twain, and William James.