Toward the end of the Civil War, some thirty Jewish veterans were buried in the Cemetery for Hebrew Confederate Soldiers in Richmond, Virginia. They were not locals but rather hailed from Mississippi, Texas, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, and Louisiana, and their bodies were brought to Richmond after Confederate military cemeteries refused to inter them alongside their fellow soldiers. Why would military cemeteries make such strict distinctions among the glorious dead? And, perhaps more to the point, why would Jews fight for a cause that disdained their sacrifice? In the postwar period, the politics of Jewish courage and wartime sympathies would form a kind of genre of its own—one that sought to defend American Jews from a new libel by enshrining their service. These monuments were not limited to the former capitals of the Confederacy; even today, some can still be found in the most unlikely places.

In 1901 the magazine Confederate Veteran reported that the newly formed Cincinnati chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy had put up, as part of its first initiative, a monument to a veteran named Felix Moses. Monuments and memorials to the glorious Confederate dead were constantly going up in the early twentieth century, part of a concerted effort to enshrine the Lost Cause and protect it from alleged Northern revisionism. On May 5, the article continued, “a plain but appropriate stone was placed over his resting place in the Jewish cemetery. Professor John Uri Lloyd…who has every year decorated and cared for the grave of Felix Moses, gathered as many as possible of Moses’ old friends and veterans to attend the commemoration services.” It was an interfaith affair, according to a local newspaper: “The chapel was crowded to its utmost with all classes and creeds, making in itself an excellent testimonial to the reunited North and South.” The Daughters had draped the chapel in Walnut Hills with Confederate flags. The inscription on the black granite stone read:

felix moses

a

confederate

soldier

and

a true friend

1827–1886

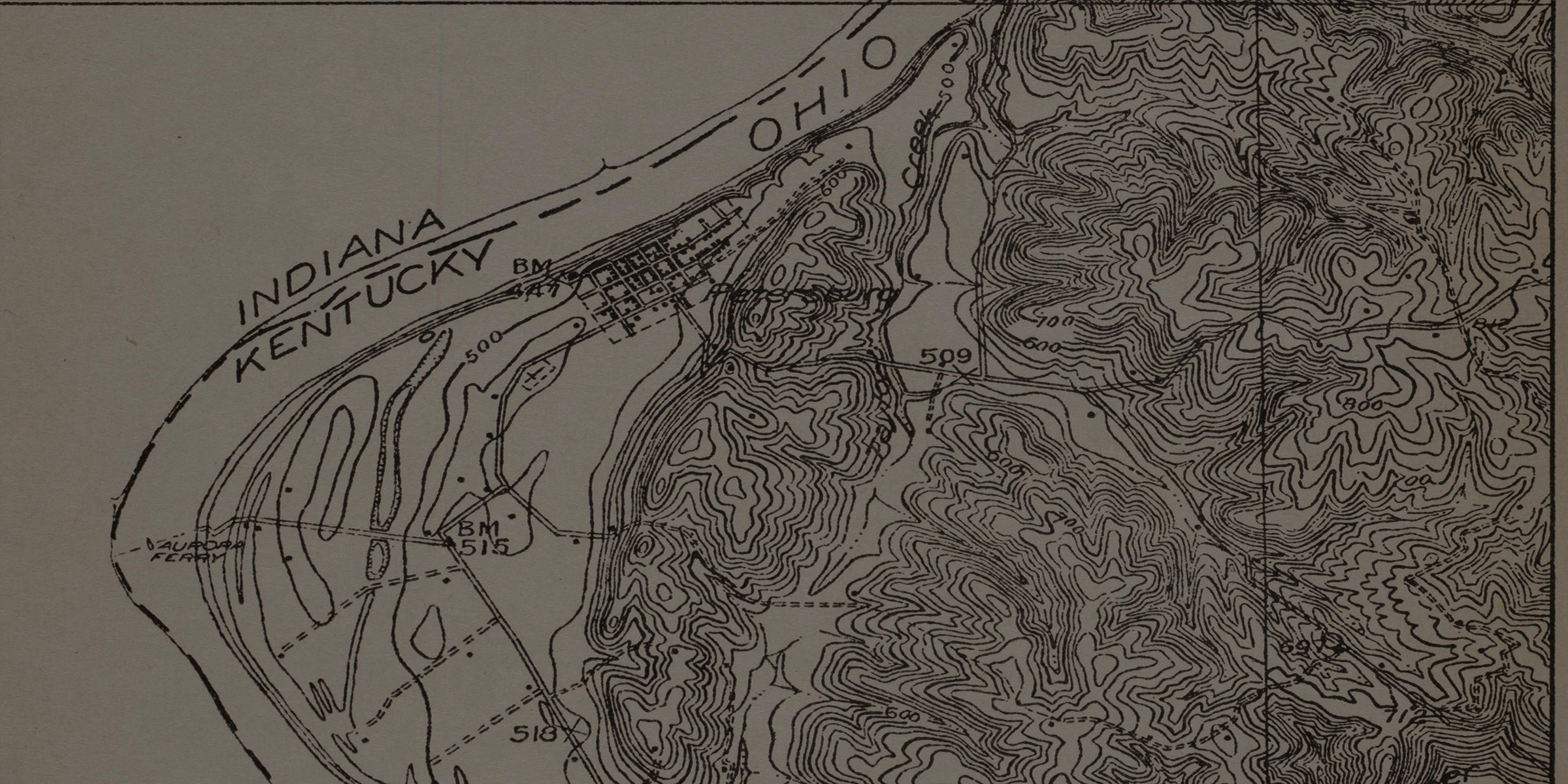

It may have been unclear to readers of the Confederate Veteran why the Daughters of the Confederacy had singled out Moses—or Mose, as he was known—for special distinction. Even now, the few facts that we have about him often contradict one another; at times, he appears as “Phelix Masses.” According to the War Department, in December 1862 Private Moses had joined Brigadier General Simon Bolivar Buckner’s troops at Bowling Green, and was discharged a year later “by reason of expiration of term of service.” On January 10, 1863, he reenlisted in Company G of the Ninth Regiment, Kentucky Cavalry, only to be captured on December 28 in Charleston, Tennessee. In 1864 he and other Confederate prisoners of war were transferred to a military prison in Rock Island, Illinois. And in March 1865 he was exchanged for Union prisoners, swearing “the oath of allegiance to the United States” in May. His service record lists his birthplace as “Sutburg, Kingdom of France,” his age as thirty-seven years, “height, 5ft. 4in.; complexion, dark; eyes, blue; hair, black.” (In his last military record he has gray eyes and has somehow managed to grow four inches, to 5′8″). Though undoubtedly brave, Moses does not appear to have been a particularly gifted guerrilla soldier. He was neither a war hero like Abraham Charles Myers, namesake of the Florida city of Fort Myers, nor a Medal of Honor recipient like Benjamin B. Levy. Moses survived the war and ended up buried in Ohio in March 1886, after he was found floating among the willows of the Ohio River near Rising Sun, Indiana. The Boone County Recorder later claimed he was the victim of a violent struggle aboard a boat on his way home to Boone County from Louisville after an apparent robbery gone wrong.

The inconvenient details of Moses’ demise went unmentioned in his epitaph and during its unveiling. His tragic end did not fit the arc of the story that Confederate hagiographers wished to tell; instead, the dedication of a memorial some fifteen years after his death was probably due to his happy deviation from what they considered the racial norm: “a rebuke,” wrote the prominent journalist Isaac F. Marcosson in 1900, “to the prejudice that the Jew is not a fighting man.” According to a 1901 article in the Cincinnati Enquirer, Lloyd claimed that Moses had “sold his horse and wagon and journeyed South to join the Confederate Army, honest in his conviction that the wearers of the gray were in the right.” But in the book he later published about Moses, Lloyd wrote that Moses had seen combat only because of a promise he had made to the mother of a young Boone County boy he accompanied into battle. Though Moses did not manage to bring the soldier boy home safely—a tragic scene the book belabors—he nonetheless “wore the gray of the Confederacy and he wore it well.”

The eulogies that afternoon were full of nostalgia and not a small amount of fantasy, turning Moses into a figment of the Good Old Days—a wishful symbol that was fed and kept alive with plaques and memorials, some designed by the Jewish veteran and sculptor Moses Jacob Ezekiel, who created some of the most famous statues to the Lost Cause. Union Army veteran and former Ohio secretary of state Benjamin Rush Cowen spoke last. “We are met here to honor the memory of a man,” he proclaimed, “not because he fought for the Lost Cause, but because he was a man, faithful to civic and social duties and a true friend.” For him, Moses was “a worthy descendant of that glorious race which reclaimed a country from barbarism and idolatry and preserved to the world its most precious legacy of religion, of philosophy, of jurisprudence, and of literature, and he was true to the traditions of his ancestry.” In his fulsome praise of the Israelites who settled ancient Canaan, Cowen simultaneously flattered “that glorious race” of pioneers who murdered and dispossessed the native “idolaters” of what today we call the state of Kentucky.

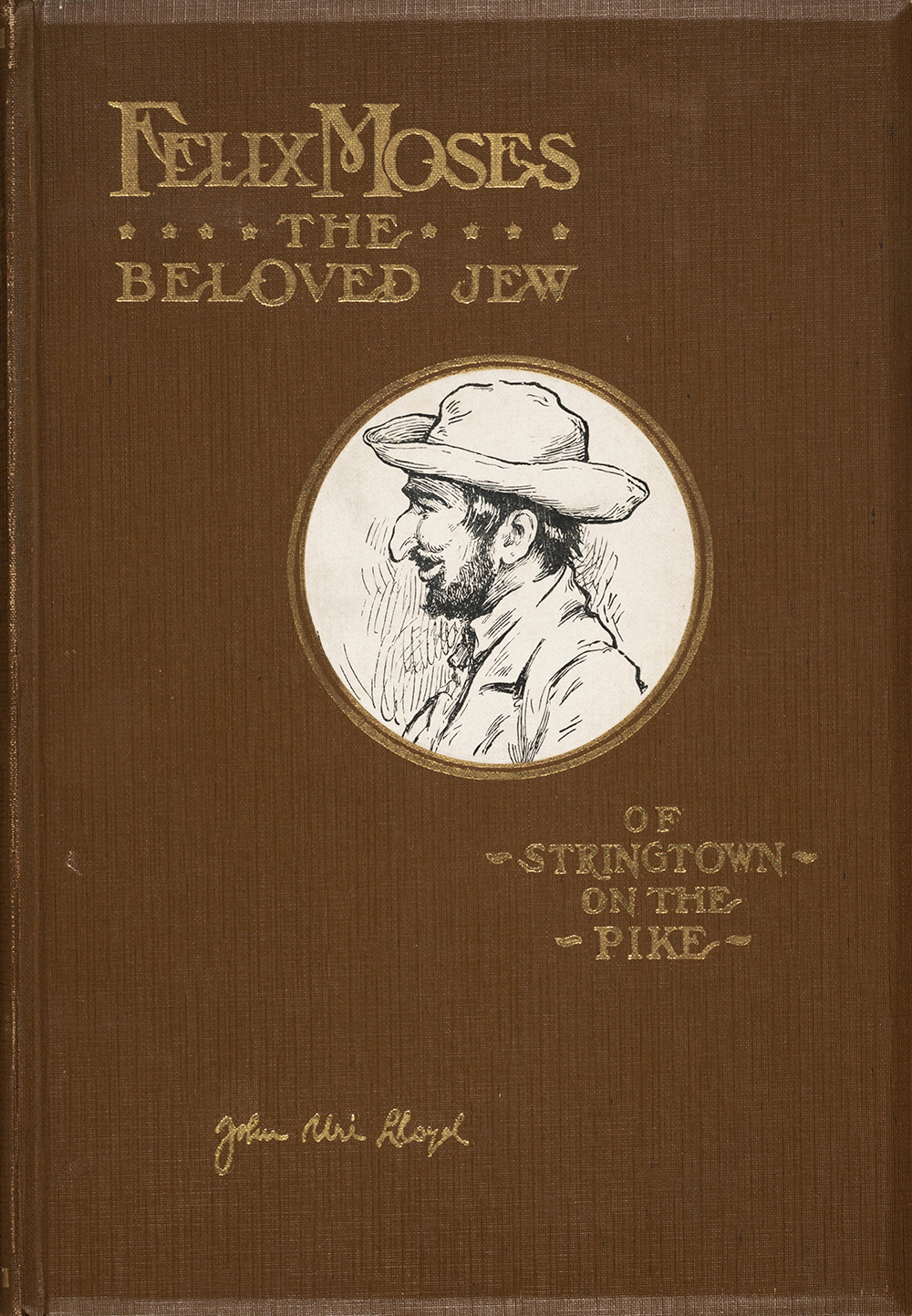

Nearly all of what we know about Moses comes from Lloyd, the writer who dutifully cared for his friend’s grave and expanded and embellished the epitaph upon it in the novel he published some thirty years later, Felix Moses, the Beloved Jew of Stringtown on the Pike: Pages from the Life Experiences of a Unique Character—a Man Whose Romantic Record Challenges Imagination. The book, an entry in the familiar “based on a true story” fiction genre, indeed challenges imagination, but not necessarily in the ways Lloyd intended. It begins with a talking clock that suggests Lloyd take over the narrative duties by spilling only the facts of Moses’ life. He obliges, proceeding to introduce a man too saintly to be real, a holy fool with a “pleasant smile” and “cheerful voice” who also happens to be “as simple as a child, as modest as a schoolgirl, as brave as the bravest.” In essence, the book reads as a variation on the “loyal slave” myth championed by supporters of the Lost Cause.

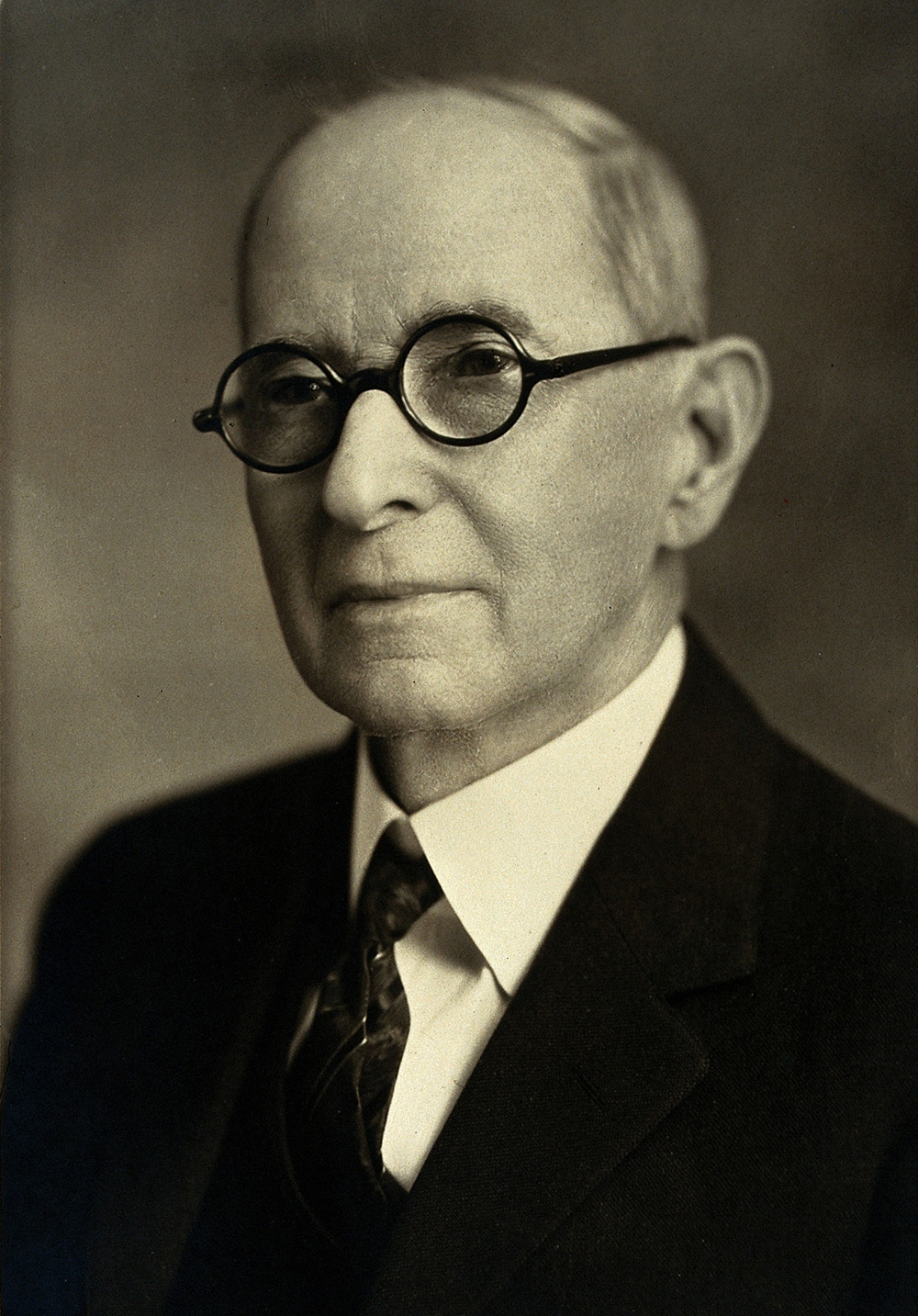

Best remembered today for his 1895 hollow-earth adventure story Etidorhpa, or the End of the Earth (Aphrodite spelled backward), he was simultaneously a successful local pharmacist; a leader in the Cincinnati-based eclectic-medicine movement; a pioneer in the field of pharmacognosy, the science of deriving medicines from plants; and, by the turn of the century, a novelist of some notoriety. He explored the botanical diversity of Ohio’s Miami Valley, and the Smithsonian Institution once tasked him with conducting a scientific survey of licorice in the Ottoman Empire. In addition to running Lloyd Brothers Pharmacists Inc. (today owned by Eli Lilly and Co.), he and his two younger brothers were prominent members of the Cincinnati intelligentsia, as well as major collectors of books, manuscripts, and miscellaneous objects from around the world. Their vast trove of some 150,000 volumes and archival materials is housed at the Lloyd Library and Museum on Plum Street.

In the last decades before his 1936 death (of pneumonia, in sunny Van Nuys, California), Lloyd aspired to capture the popular imagination through a series of sentimental books brimming with Kentucky geography, ethnography, ephemera, gossip, proverbs, lore, flora and fauna, poetry and song. Led by authors like the novelist James Lane Allen, the local-color movement was a literary trend based on nostalgia, argues scholar Michael A. Flannery, becoming something of a “national obsession” following the Civil War, when the unique microcosms it sought to describe were already disappearing. In Etidorhpa, Lloyd described a cave in northern Kentucky filled with giant psychedelic fungi that served as a portal to another world. Felix Moses was the penultimate and perhaps the most ambitious of his six Boone County books. It has all the main features of the local-color genre, including “persistent, often excessive, use of dialect; an interest in superstition and the supernatural”; and the narrative tic of footnoting frequent, folksy digressions. I learned more than I wanted to know about puncheon floors, burgoo preparation, and mammoth fossils, but I never did find out what became of old Mose.

Even when we manage to hear Moses’ voice in Lloyd’s book, it comes adulterated and filtered through that of others until little is left but a broad stereotype. Even for a novel that faithfully follows all the unsubtle local-color conventions, Felix Moses is profoundly paternalistic and seems to feature every conceivable caricature of the Jew. Here is Moses pledging to the soldier boy’s mother that he will bring him home safely:

“Will you really go with him, Mose?” she asked earnestly. “Do you mean it?”

“Sure I vill go, and vhen he comes back mit me I vill tell you how this boy makes the best soldier in the whole rebel army. I sure vill bring back a—vhat you calls him—a hero to you, mother.”

Lloyd fixates on Moses’ prominent nose, which allegedly “dominated the entire face,” and mentions that friends in Cincinnati had affectionately nicknamed him “Nosey Mosey.” In the opening pages, set “many decades ago,” our stranger arrives carrying a literal carpetbag down a gangplank somewhere near the village of Ghent, Kentucky. Completely alone in the woods, he is “without acquaintance near or far, the representative of a great and an historic people, as his features unmistakably indicated.”

From the moment he first comes ashore, Moses is forced to define and defend himself. He is taken for a spy by a group of Know Nothings and attacked, and then interrogated by a fanatic convinced that “to kill a Jew was his duty, somewhat akin to that of ridding the Kentucky forest of ‘varmints.’ ” Exhausted, he falls asleep and dreams of his youth amid the poverty and violence of some imaginary Eastern European ghetto. Through his youthful eyes we witness a blood libel, the murder of his parents, a pogrom, and Jews being packed into a synagogue as the ghetto burns to the ground. Young Felix miraculously escapes with his grandmother and is smuggled into another ghetto, where they find shelter with her long-lost brother. (For some reason, the Jews in this section of the book speak in King James thines and thous.) Moses is the sole survivor, by which we are meant to understand that—like his namesake—he has been rescued for a greater purpose.

War quickly overwhelms whatever plot there is to begin with. Lloyd introduces the reader to a tragic mother with two sons; the older joins the Union, and the junior, too young to follow his brother, intends to join General Morgan’s Raiders down South. The mother is clearly meant to represent Kentucky itself, split bitterly in two by the war. Even as Moses and the younger son pay a visit to the boy’s “Mammy,” Aunt Dinah, for a farewell omen reading, and have to be hidden from the bluecoats by Dinah’s husband Cupe, the narrative remains committed to displacing slavery from its central role in the Civil War. (Lloyd, who fancied himself something of a minor folklorist and an expert on African American speech, peppers the dialogue between Cupe and Dinah with the ostensible efforts of his research: words like memberlect, preparationed, and disastrophe.)

Stringtown, where much of the book is set, was Lloyd’s idealized version of Florence, a forested hamlet in eastern Kentucky “strung along both sides of a mud road that began in Lexington and terminated in Covington.” Many of his other local-color novels take place in the same fictional location. The Pike of the book title was the old Covington-Lexington Turnpike (now U.S. 25 and 42, respectively), which was built and improved upon from 1834 to 1850 in order to make hogs and cattle available to Cincinnati, then a major center for meatpacking. This would have been the Boone County Moses entered when he first arrived in the late 1840s, one of many Jewish businesspeople who had come to seek their livelihoods in the Bluegrass territory and beyond. Moses appears to have been a typical itinerant peddler of the pre-automobile era, buying up hides, woolens, rags, and ginseng. In return, he often brought country folk the first manufactured toys, linens, and other soft goods they had ever seen. It was a lonely and dangerous way to make a living.

“Peddling in the countryside was a rough life,” writes the scholar Jacob Rader Marcus with typical understatement in Early American Jewry. Throughout the war, Major General Ulysses S. Grant often received complaints from territories under his control about dirty dealing in illicit goods by Jewish merchants and “other Vagrants,” as Colonel John V.D. Du Bois put it in his 1862 General Orders No. 2. Jews were blamed collectively for allegedly trading in cotton and, as the Chicago merchant Philip Wadsworth wrote to Grant, “taking large amounts of gold into Kentucky and Tennessee.”

In December 1862 Grant issued his infamous General Orders No. 11, which ordered all Jews to leave the areas of Tennessee, Mississippi, and Kentucky that were then under his control. According to Grant’s defenders, the order was an attempt to stifle the illegal market for Southern cotton and other goods. “The Jews, as a class, violating every regulation of trade established by the Treasury Department, and also Department orders, are hereby expelled from the Department,” Grant wrote. “Within twenty-four hours from the receipt of this order by Post Commanders, they will see that all of this class of people are furnished with passes and required to leave, and anyone returning after such notification will be arrested and held in confinement.”

Elaborating on these orders in a letter to C.P. Wolcott, the assistant secretary of war, Grant was adamant:

They come in with their carpet sacks in spite of all that can be done to prevent it. The Jews seem to be a privileged class that can travel anywhere. They will land at any wood yard or landing on the river and make their way through the country. If not permitted to buy Cotton themselves they will act as agents for someone else who will be at a military post, with Treasury permit to receive cotton and pay for it in Treasury notes which the Jew will buy up at an agreed rate, paying gold.

Though President Abraham Lincoln ordered them countermanded the following year and many cities were late to receive them, the orders were carried out in places like Holly Springs, Mississippi, and Paducah, Kentucky, where some thirty local Jewish families were forced to board a steamer with their hastily gathered belongings. Telegrams were sent in protest and newspapers like the New York Times condemned the orders, but many others gleefully approved. The Corinth War Eagle, an “occupation newspaper” published by Union soldiers, crowed that Jews were “sharks, feeding upon the soldiers. General Grant has determined to rate them a nuisance, and abate it suddenly.” The Jewish Record reported that one Jew who asked for a reason was told, “Because you are Jews, and they are neither a benefit to the Union or Confederacy.” Later, during his presidential campaign, Grant denied that any ill will had been involved; but whether he drafted the final version or not, he at least knew of and approved it. (His father, Jesse Grant, had tried to profit from his son’s position by surreptitiously promising the Mack brothers, Jewish clothing contractors from Cincinnati, a coveted cotton permit in return for a cut of the business.) In fact, many of those who disagreed with Grant’s order did so only because it applied to Jews as a whole; if it had merely excluded “Jew peddlers,” wrote Illinois representative Elihu B. Washburne to Grant, “it would be all right.”

The episode laid bare the common prejudice—voiced by Lloyd’s acquaintance Mark Twain in “Concerning the Jews,” for example—that Jews were not combatants but profiteers, which may have spurred Lloyd’s well-intentioned but crudely compensatory attempt to recast Moses as a Jewish hero. In 2020 Moses’ membership in the local Masonic lodge, his legendary fairness, and his celebrated generosity come across as evidence of a desperate attempt to wash away the stigma of foreignness. Northern Kentucky may not have been the Deep South, but it was far enough from Ohio that it would ultimately lose most of its Jewish population to Cincinnati, the city across the river where abolitionist author Harriet Beecher Stowe had conducted extensive interviews with those who had escaped from the horrors of slavery. Lloyd had witnessed many of these developments firsthand as the son of an engineer who had moved from New York to Kentucky to help build the railroad and stayed when the company he was working for went bankrupt. Having grown up in the era of rapid change, when the wilderness was converted into neat fields of corn and tobacco, Lloyd had an obvious fondness for the days of his youth and for the mythic past that had preceded it.

Lloyd doesn’t seem too eager to discuss his protagonist’s postwar life, and the book ends shortly after Moses returns from one of his many unscheduled disappearances. Of his life following the Civil War we know little other than that Moses continued to peddle furs and other goods. Once a year, he put on his best clothes and traveled to Cincinnati for the Jewish holidays. Though Lloyd treats him as if he were an orphan, Moses appears to have had a brother named David in Natchez, Mississippi, who ran a flourishing and well-known store, D. Moses and Sons. It’s not clear if the brothers were in contact following their arrival in the United States or if they had become estranged, but it seems that both first arrived in New Orleans from Alsace, part of a new wave of Jewish immigrants to the South.

The mysteries surrounding Moses’ death were never resolved. There were no suspects in the case, and no one was ever charged with his murder. Though his death was said to be the result of a robbery, nothing appeared to have been taken from him. His watch had stopped at 10:55 pm, presumably the time he went overboard. The story quickly disappeared amid the competing scrum of thousands of other tragedies, but the Boone County Recorder resuscitated it only a month after his body was first found, running a brief item insinuating that perhaps something more sinister had occurred. If the report of Moses’ demise “had said drowned, by hanging,” it noted, “it would have been as near correct as it is.” His friends said he left for vacation and never returned. In a later pamphlet, Lloyd admits that Moses was murdered and thrown into the river, gesturing vaguely at a potential motive by equipping this “gentle being” with a large hidden diamond.

A tug-of-war immediately ensued over the body in Lloyd’s dramatic reenactment. The Jews of Cincinnati claimed that Moses was one of them, had worshipped with them, and now belonged to them. But the Stringtowners had already begun an open-casket ceremony and were reluctant to turn him over to strangers. “He was proud to be called ‘our Jew,’ ” they countered, “and we were glad to have it so.” It’s a bizarrely possessive but common sentiment that also informs Lloyd’s relationship to his African American characters: the claim that intimacy confers a special understanding “only partly comprehended by Northerners,” including many of his readers. He presumes to understand things he cannot possibly know, such as when he mentions that “refreshments were served by drilled negro servants, who knew their places and were proud to fill them capably.” “God help the negro,” Lloyd had written in his novel Warwick of the Knobs: A Story of Stringtown County, “when the vindictive invader tears him from his watchful owner’s care and throws him helpless on the world.”

Care is a strange word for that relationship. In reading Lloyd’s book and thinking about Moses, I came to be as suspicious of the word love. Everyone claims to have loved Felix Moses, and every one of them truly seems to believe it. But love—the kind that mythologizes and enshrines—can also be a one-sided affair. Everyone may have truly loved Moses, from the preachers who accepted his donations to the Masons who remembered him as Junior Deacon of Good Faith Lodge, No. 95. But did any of them truly know him? The myth of old Mose in many ways obscures and makes it more difficult to get a sense of who he was other than as a representative of his race, the archetype of the Wandering Jew. Today, the book is a mere curiosity, a portal into that past which is not even past; it’s hard to imagine anyone picking it up for the sheer prose. Yet it demonstrates how particular versions of our past enable the invention of new identities and forms of politics, and cautions us against putting faith in monuments of any kind—a reminder that all statues are idols.

The author thanks Erin Campbell of the Lloyd Library and Museum for her assistance.