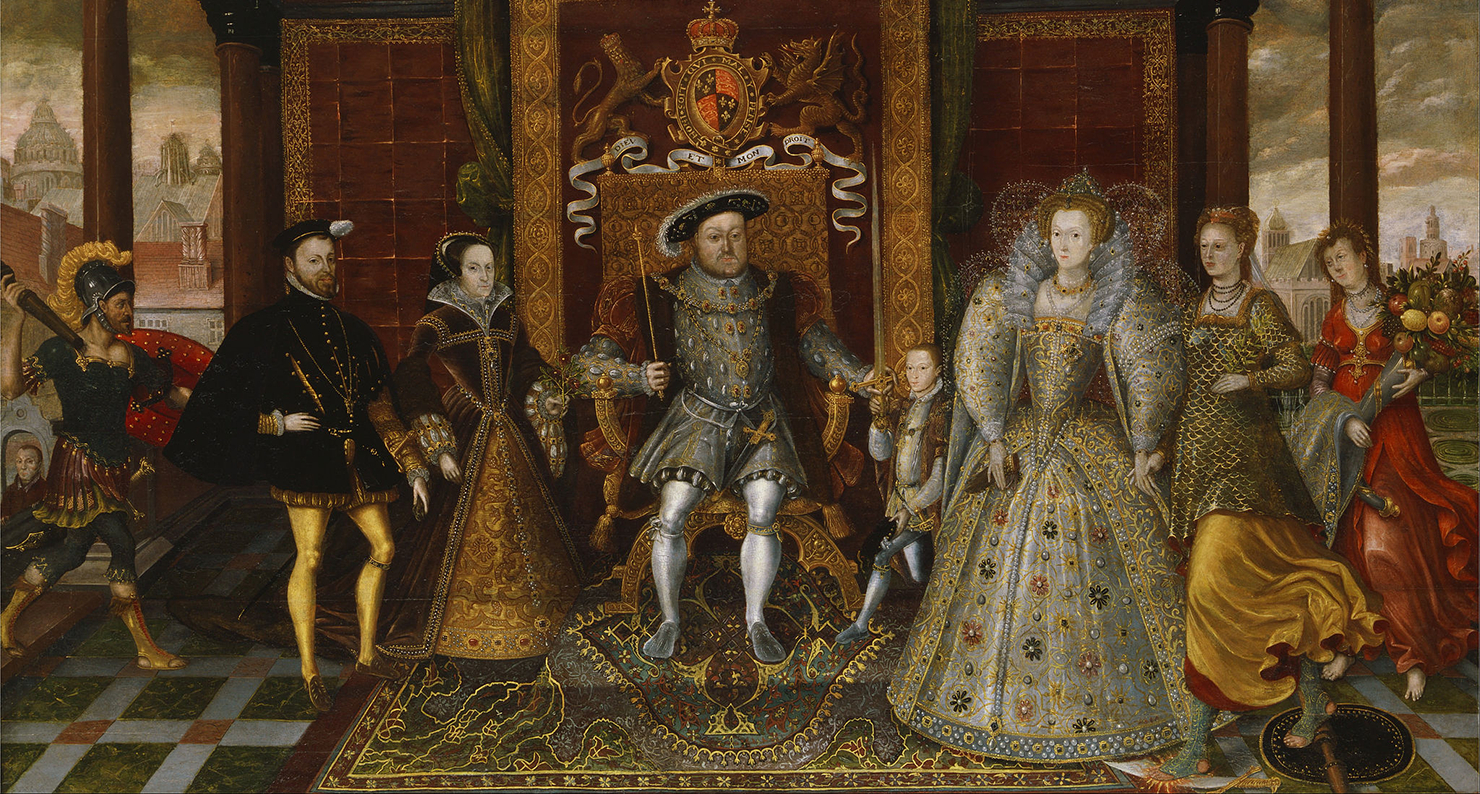

An Allegory of the Tudor Succession: The Family of Henry VIII, by unknown artist, c. 1590. Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.

Far from being the sickly child that history has often portrayed him as, Edward VI was a robust little boy and, as Thomas Cromwell put it, “sucketh like a child of his puissance.” But Henry VIII was taking no chances. He ordered that the son whom he referred to as “this whole realm’s most precious jewel” should remain at Hampton Court, well away from the perpetual sickness that plagued the capital. More conscious of hygiene than most of his contemporaries, the king provided a new washhouse at the palace and ordered that the walls, floors, and ceilings of Edward’s apartments should be washed down several times a day. Everything that might be handled by the prince had first to be thoroughly cleaned. Only those of the rank of knight or above were permitted to attend the prince, and they must all be scrupulously clean before touching him, as well as free from sickness. They were not permitted to speak with persons suspected of having been in contact with the plague, and they were strictly forbidden from visiting London during the summer, when outbreaks of the disease most commonly occurred. Any servant who fell ill was ordered to leave the household at once. Serving boys and dogs were specifically barred because they were clumsy and prone to infection.

Situated in the north range of Chapel Court, Edward’s suite of rooms was laid out in a similar manner to the king’s. A magnificent cradle of state took pride of place in the presence chamber, where privileged visitors could catch a glimpse of the precious infant. This was accessed via a processional stair and a heavily guarded watching chamber. Edward’s privy chamber served as a day nursery, and he slept in the bedchamber or “rocking chamber” in a cradle protected from the sun by a canopy. Next door was a bathroom and garderobe, which still survives.

Henry also commissioned a privy kitchen for his son at Hampton Court in order to ensure that there was no contamination from the main kitchens that served the rest of the household. Once he had been weaned, all of the prince’s food would be tested by a servant before being given to him; his clothes were washed, brushed, and tried on before being worn; and any new garments were to be washed, dried by the fire, and anointed with perfume before they were deemed fit for Edward to wear. No detail was overlooked. A rare glimpse of the prince’s bedchamber at Hampton Court is provided by a reference to the making of “a frame of scaffold polls over the prince’s bed to keep away the heat of the sun.” The same strict standards were applied to the other residences that Edward and his sizeable household stayed in, notably Richmond Palace, Havering-atte-Bower, and Hunsdon.

But all of the king’s assiduous care was administered at a distance: Henry adhered to royal tradition by being as absent a father to Edward as he was to Mary and Elizabeth. A rare glimpse of him paying a visit to his infant son was recorded in May 1538, when he spent the day with Edward “dallying with him in his arms a long space and so holding him in a window to the sight and great comfort of all the people.”

By contrast, Edward’s elder half-sister Mary was a regular visitor to the nursery. Aged twenty-one at the time of his birth, she had a strong maternal instinct and lavished affection on her motherless baby brother. She also gave him various gifts—all of which were more personal (and no doubt welcome) than those he received from his father. At New Year 1539, for example, she gave him a made-to-measure coat of crimson satin embroidered with gold and pearls and with sleeves of tinsel. The king, meanwhile, presented him with a lavish gilt standing cup—the same gift that he might have given one of his adult courtiers. Throughout his childhood, and before their relationship was soured by differing religious views, Edward was very fond of his elder sister. He “took special content” in her company and once assured her that despite his infrequent letters: “I love you most.” He was also fond of his other half-sister Elizabeth, to whom he was much closer in age. Elizabeth had learned to sew by the age of six and she made a shirt of cambric or fine white linen for her brother. Upon trying out a new quill, she wrote “Edwardus” across the page in her careful, childlike scrawl.

For the first years of his life, Edward was raised “among the women,” as he recalled in his journal some time later. They were responsible for teaching the young prince these fundamentals of etiquette, as well as for catering to his every need. They included his nurse, “Mother Jack,” and Sybil Penn, who took over from her in October 1538 and remained in that post until 1544. Edward adored Sybil and on one occasion, when she carried him in to be presented to some visiting dignitaries at court, the young boy was overcome with shyness and refused to look at them, but clung to his nurse and buried his face in her neck. Sybil’s brother-in-law, William Sidney, a member of the king’s privy chamber, was appointed Chamberlain to the prince. Numerous other officials were selected for Edward’s care, and in its first year alone his household cost £6,500 (the equivalent of almost £2 million) to administer.

Principal among Edward’s household was the experienced Lady Margaret Bryan, who had proved her ability and trustworthiness as the “Lady Governess” to both of the king’s daughters, Mary and Elizabeth. Capable and efficient, she had been a stern mistress to the princesses, but she had something of a soft spot for their baby brother. In March 1539, she reported the seventeen-month-old prince’s progress to Cromwell: “My lord Prince is in good health and merry. Would to God the King and your Lordship had seen him last night. The minstrels played, and his Grace danced and played so wantonly that he could not stand still.”

The troupe of minstrels described by Lady Bryan had been appointed to the prince by his indulgent father, who was determined that he should have everything that his young heart might desire. Little wonder that the few visitors who were permitted access to his apartments described him as a contented child. He was also a strong one. In August 1539, Lord Chancellor Audley paid a visit to the prince’s nursery and reported back to Cromwell that Edward “waxeth firm and stiff.” He could stand unaided and would probably have been able to walk if his nursemaids had let him.

Although Henry undoubtedly devoted the greatest attention to his precious son and heir, he was a doting (if distant) father to all of his children. Among his personal possessions at Whitehall was a collection of mementos from their infancy. An inventory of the palace includes a “little box of crimson satin embroidered, containing shirts and other things for young children.” Whether these were keepsakes from Edward, Mary, and Elizabeth, or were made for the short-lived babies and pregnancies of Catherine of Aragon and Anne Boleyn, is impossible to say.

Closeted away from the rest of the world in a succession of luxurious nurseries, Prince Edward had been allowed to indulge in a diet of rich foods. One tactful visitor noted in October 1541 that Edward was “well fed,” hastily adding that he was also “handsome” and “remarkably tall for his age.” Still under the supervision of Lady Bryan and the other women of his household, Edward was already being groomed for his future role.

All Tudor children, regardless of their status, had to learn a complex set of social rules and behaviors almost from birth. From the time that Edward took his first, tottering steps he would have been taught a range of postures for walking, standing, or sitting that communicated his superior social position. He was forbidden from crossing his arms because the great scholar Erasmus had deemed it foolish. A miniature of Will Somer, the favorite fool of Edward’s father, shows him in just such a pose. By contrast, for a man to stand with his legs apart, hips pushed forward and gaze fixed straight ahead was indicative of strength, virility, and martial prowess. Henry VIII had famously adopted this pose for Holbein’s full-length portrait of him at the height of his powers.

In order to distinguish themselves from the laboring classes, most of whom worked the fields in a slow, plodding gait, young noblemen would walk with a swagger, thrusting their hips forward so that their swords, bucklers (shields), or purses swung about noisily, announcing their presence. It is from this showy practice that the word “swashbuckler” originates.

Perfect posture was only achieved if one was taught it from the earliest days of childhood. It was not a skill that could be learned in adulthood, so the origins of those who managed to rise through the ranks as a result of trade or good fortune would be forever betrayed by the way that they stood or walked. Edward had received formal instruction in the arts of movement from his tutors and dancing masters. As these arts were subject to the whims of fashion, his masters ensured that he adhered to the very latest styles of posture.

People living in the sixteenth century had to negotiate a minefield of different codes of conduct that were devised to create a strict pecking order between the sexes and social classes. Boys were encouraged to be bold and assertive, as described by Thomas Elyot in his treatise of 1531: “A man in his natural perfection is fierce, hardy, strong in opinion, covetous of glory, desirous of knowledge.” Women, on the other hand, were expected to be “mild, timorous, tractable, benign, of sure remembrance, and shamefaced.” It is interesting to note that Edward’s half-sister Elizabeth, who was four years his senior and shared his education, hardly conformed to this ideal.

Age commanded a great deal of respect in Tudor times, so children were expected to show deference to almost all adults, even those who were significantly below them on the social scale. Erasmus wrote a code of conduct for children entitled Civilitie of Childhood. First published in 1532, this gained widespread circulation, running into several editions, and would almost certainly have influenced the upbringing of Henry VIII’s two younger children. One of the fundamentals of polite behavior among children was the art of bowing and curtseying. Edward and Elizabeth would have been taught this from the age of four. A simple doff of the cap for a boy and a little bobbing movement for a girl would suffice at this young age. A more formal bow, such as Edward might have made to his father the king, would have involved dropping to one knee. Elizabeth, meanwhile, would have been taught to keep her head perfectly erect and her back very straight as her eyes were lowered. Her hands would be open and slightly to the side, thus making the whole effect very like a plié in ballet.

There was no shortage of manners books published in the Tudor period, each of which set down strict rules for every childhood activity: from dressing and eating to talking and playing. No circumstance was overlooked. If a child had a runny nose but no handkerchief, they were instructed to pinch the phlegm away with finger and thumb and allow it to drop to the ground, where it should be trodden in so that it should not sully the shoes of a passer-by. Wiping your nose on your sleeve was strictly forbidden, as was nose picking, squinting, pulling a sad face, resting your elbow on the table, and talking with your mouth full.

Edward had turned six years old shortly after Katherine Parr had married his father. This age (also known as “breeching” because it was accompanied by a change to adult-style attire) was viewed as a milestone by the Tudors, who believed that it marked the beginning of adulthood. An order of clothing from March 1544 provided the young prince with two doublets and matching slops (loose breeches) of crimson velvet and black satin, with buttons and loops of Venice gold. The following year, the king’s skinner, Thomas Addington, provided the prince with a range of furs, including thirty sable skins. At the same time, Edward’s private apartments were restyled so that they more closely resembled those of his father, and were stuffed with every conceivable luxury. The walls were hung with Flemish tapestries depicting classical and biblical scenes and his books were embellished with covers of enameled gold set with rubies, sapphires, and diamonds. Even his cutlery was studded with precious stones and his napkins sparkled with gold and silver thread.

The transformation of Edward’s household was more than simply decorative. Any female attendants were replaced so that his became a predominantly male establishment. Edward was also assigned a tutor, Richard Cox (described as “the best schoolmaster of our time”), with John Cheke acting as deputy, “for the better instruction of a Prince, and the diligent teaching of such children as be appointed to attend him.” The serious business of molding him into a future king had begun.

Excerpted from The Private Lives of the Tudors: Uncovering the Secrets of Britain’s Greatest Dynasty by Tracy Borman. Copyright © 2016 by Tracy Borman. Reprinted with permission of the publisher, Grove Press, an imprint of Grove Atlantic, Inc. All rights reserved.