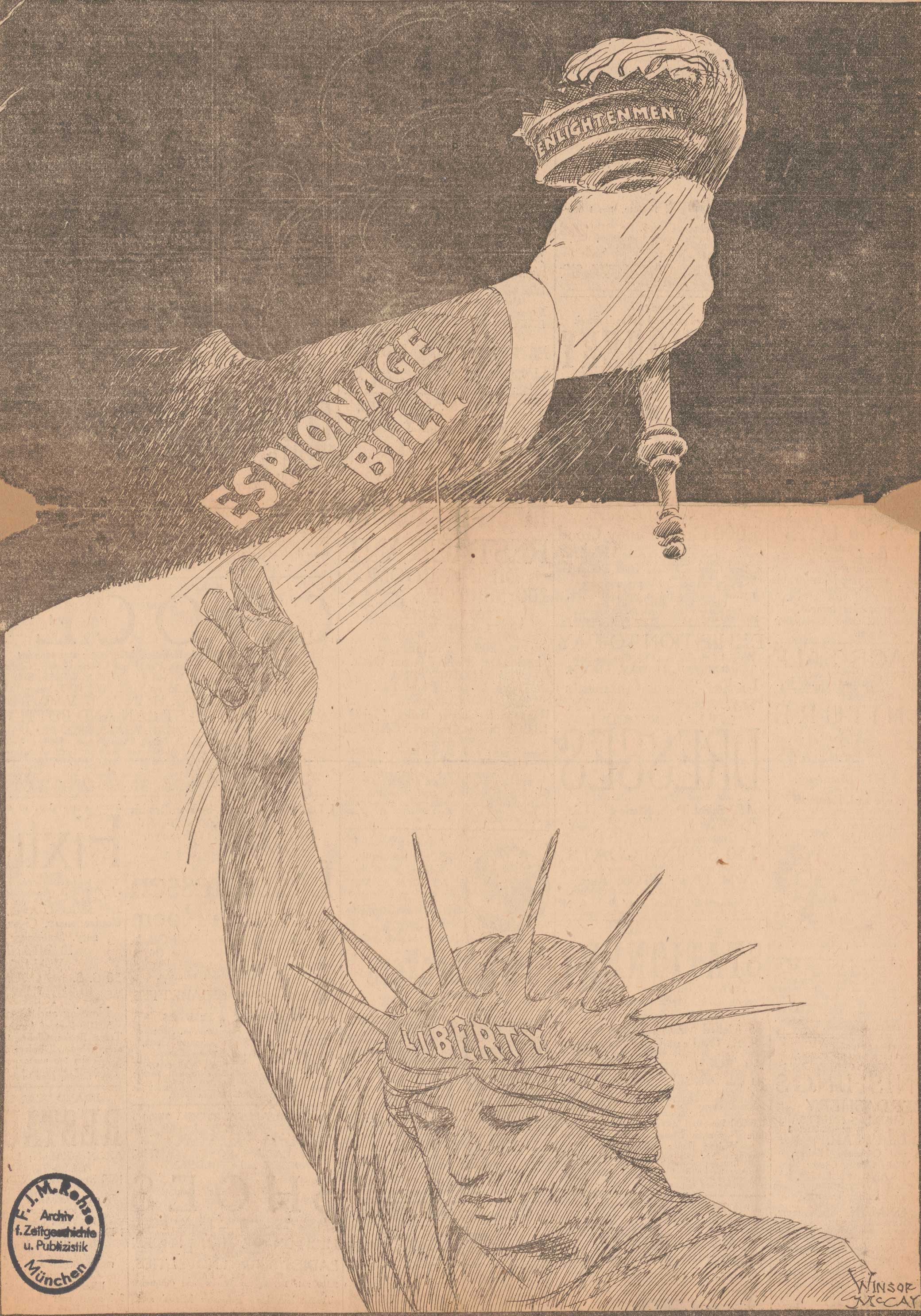

Must Liberty’s Light Go Out?, by Winsor McCay, 1917. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

On The World in Time podcast in October 2022, Lewis H. Lapham spoke with Adam Hochschild about American Midnight: The Great War, a Violent Peace, and Democracy’s Forgotten Crisis. This transcript has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Lewis H. Lapham: You write about the years 1917 to 1921, the years during and after a world war fought to make the world safe for democracy, but proving to be the ruin of democracy in America. Tell us: Who are the heroes and villains of the tale?

Adam Hochschild: Why don’t we begin with the scene that constitutes my first chapter, which I think of as the day when this very dark period in American life began. It was April 2, 1917. And remember, by this point the nations of the Old World had been fighting ferociously in Europe for nearly three years. Millions of people had been killed in the First World War. The United States was not yet in the war, although we’d been selling large quantities of arms to Britain and France, making lots of money from it. Finally, the time came when President Woodrow Wilson wanted his country to join the war for a variety of reasons. He was a great Anglophile. I think he and the people around him felt that unless the United States joined the war, it would have no influence in crafting the peace and the world to come after the war. Furthermore, unless the U.S. joined the war on the side of the allies, Americans who had bought British and French and Russian war bonds would never get their money back. Of course, those who bought tsarist Russian war bonds never did get their money back. So for this mixture of somewhat idealistic and very materialistic reasons, Wilson wanted the United States to join the war.

So on April 2, 1917, he sent word that he wanted to address a joint session of Congress. A new Congress had been elected the previous year, but it didn’t start meeting until April. Both houses of Congress assembled to hear him. It was clearly going to be a momentous gathering because everybody expected some kind of announcement like this was coming, some kind of request to Congress. So for the first time that anybody could remember, foreign diplomats in Washington were there in the House of Representatives chamber in evening dress. The justices of the Supreme Court were all there; all kinds of visitors, distinguished and undistinguished, who could wrangle invitations were there in the balconies. Somebody who was very good at getting himself included in the presidential party at moments like this was sitting up in the gallery—along with Wilson’s wife and daughters and some other Wilson relatives—a junior official: assistant secretary of the navy Franklin D. Roosevelt.

Wilson came before Congress and started speaking. People were not sure whether he was going to ask for some sort of limited war, maybe authorizing American ships to sink German submarines or whatever. But at the moment Wilson made clear he was going to ask for conscription, asking Americans to send a large army to Europe, absolute hysteria broke out, a kind of hysteria of joy that at last the United States was joining the greatest war the world had ever seen. The person who leapt to his feet and led the cheering was the chief justice of the U.S. Supreme Court, Edward White of Louisiana, who was himself a Confederate veteran. Witnesses around him describe him weeping tears of joy as he applauded as loudly as he could, leaping to his feet and leading the chamber in a standing ovation.

I’d like to pause at that moment and ask what was it that allowed somebody who actually was not in Wilson’s party, who was very conservative, to weep tears of joy at the prospect that millions of young American men were going to be sent to Europe to risk their lives and possibly die in this absolutely insane war. Well, wars always have a kind of insanity around them. You and I talked about another book of mine on that subject about a dozen years ago as being particularly insane, because [World War I] was a war that remade the world for the worse in every way. But I think there is always a hunger in all societies, including our own, to feel you’re part of some great worldwide crusade, and the U.S. joining the First World War and becoming part of the largest conflict that history had ever seen was that moment not just for Chief Justice Edward White but for millions of other Americans as well.

So there was a frenzy of hyperpatriotism that spread across the land. And this was something useful to our business and government. Why? Because it gave them the excuse to crush the labor movement. Business and organized labor had been battling for years. Dozens of workers were killed in strikes every year. Some seventy people were killed in 1913 and 1914 alone in miner strikes in Colorado. And now every worker who went on strike could be accused of impeding the war effort. A couple of months after Wilson’s speech, of course Congress acceded to his wishes and declared war, although some people voted “no.” But just as an example of how the war was used and domestic battles that were already going on in the summer of 1917, a couple of months later there was a copper miners’ strike in Bisbee, Arizona. A sheriff’s posse, several thousand men, went through town, rounded up two thousand striking miners, rousing them out of their beds at dawn at gunpoint, and demanded that they go back to work, saying that they were impeding the war effort if they continued striking. More than a thousand of them who refused to go back to work were held under the broiling hot sun on a baseball field for a couple of hours and then put into a freight train—cattle cars for maneuver and guarded by armed men on the rooftops of these trains, 180 miles through the desert and dumped in an army stockade. So this was one of the ways in which going to war was used as an excuse to intensify battles that were already going on at home.

LHL: And then shortly after that same summer, another strike in Butte, Montana.

AH: That’s right. This was also a miners’ strike protest in response to what still remains, I think, the largest hard-rock mining disaster in American history. More than 160 miners were killed in an underground fire in a mine in Butte, Montana. The Wobblies, the Industrial Workers of the World, the country’s most militant and most colorful labor union—they had the best songs; they had the best posters—a Wobbly organizer named Frank Little went to Butte to try to organize the miners so that they wouldn’t have accidents like this in the future. In the middle of the night a group of masked men came into the boardinghouse where he was staying, took him out of his bed in his underwear, tied a rope around him, dragged him behind a car to a railroad bridge on the outside of town, and hanged him. His name was Frank Little, and Vice President Thomas Marshall quipped that a little hanging goes a long way in suppressing labor unrest, a very cruel and cynical thing to say. So we had another instance of how this war hysteria was used to carry on domestic battles here.

LHL: The National Guard occupied Butte for the rest of the war, right?

AH: That’s right. They were there for, I believe, three years, and there were no more strikes there as a result of that. And later on during this period, particularly two years later in the summer of 1919, several cities in the United States—such as Omaha, Nebraska; Gary, Indiana; and a couple of other places—were put under martial law in response to more labor unrest and the worst racial rioting that the United States had seen in decades. We always talk about these things in the summer of 1919 as race riots, but they really should be called white riots because in almost all cases they were started by the white inhabitants of these cities who were very upset at large numbers of Black people moving to the North. They were trying to get out of the South, where lynchings were going on at a rate of about one per week. Around the country there were more than seventy lynchings in 1919 alone. White people in the North didn’t like it. Furthermore, it was a very nasty time economically because in 1919, the war was over. Four million American servicemen were being let out of the armed forces. Nearly 400,000 of them were Black, and they were competing with white veterans for scarce jobs. The jobs were scarce because the factories making tanks and guns, warships and so on, had closed down. So that increased the temperature on the racial front, yet another of the already existing conflicts that got intensely inflamed during this period.

LHL: Wilson himself was a Southerner and a white supremacist, avowedly so. So we have that going on, too.

AH: That’s right. He was from Virginia. He had actually grown up in Georgia. And as a boy, he and his family—who were horrified by this—had seen Jefferson Davis, the president of the Confederacy, being marched by Union soldiers through the streets of Augusta, Georgia, on his way to prison. So Wilson grew up in a very segregationist atmosphere. His father was a minister who preached that the Bible sanctified slavery. Wilson was an accomplished historian, president of Princeton University, wrote more than a dozen books. But he took in his writing a startlingly benign view of slavery, and he was most comfortable around other white Southerners. Both of his wives were white Southerners. The people closest to him—his doctor, his chief adviser Edward House, roughly half of his cabinet—were white Southerners, very conservative on the racial front. And indeed what little integration had happened in the federal government by the time Wilson took power for the first time in 1913 was undone in his two terms, and the percentage of Black people working in the federal government actually decreased during that time.

LHL: In some of his writings, he actually said that only the white Anglo-Saxons were capable of self-government.

AH: That’s true. He was not only a white supremacist, but like many people in the United States at that time he was—how could one say?—sort of an Anglo-Saxon supremacist. Because we have to remember that this was a time in American history when many people whom we think of as white today, Jews, Italian and Polish Americans, and so on, had not yet become white, so to speak, in the eyes of those Americans whose ancestors came here earlier. And Wilson was very proud of the fact that he was of Anglo-Saxon stock. And indeed, in his first cabinet, all ten members of it were white Anglo-Saxon Protestant.

LHL: Another person who at the time was fiercely Anglo-Saxon was Teddy Roosevelt.

AH: That’s right. And Teddy Roosevelt is very much a character in this book. He was no longer president, of course, in 1917, but he very much wanted to be president. Teddy Roosevelt is a writer’s dream to write about because he is so colorful, so opinionated, so explosive, and firing off with his opinions on every conceivable subject, including Anglo-Saxon supremacy and the role of women—which was to stay home and give birth to lots of children so as to increase the number of Anglo-Saxons in the world.

He also was a huge enthusiast for the war and begged Wilson to let him lead a large force of volunteers to Europe. Roosevelt was fifty-nine years old at this point, which is rather old for an active-duty soldier. But he believed in battle for its own sake, that it was good for the soul. It would be good for the American soul to be involved in this great, great crusade. So he lobbied Wilson, trying to get himself sent to Europe to lead this large force of volunteers. He and Wilson absolutely loathed each other. They were very different in style: Roosevelt kind of strident and histrionic, Wilson very professorial and laid-back. And they hated each other. Each privately said all sorts of nasty things about the other. Wilson did not send Roosevelt to lead a volunteer force to Europe; the army put the kibosh on that. All four of Roosevelt’s sons entered the war, and one of them was killed. Young Quentin Roosevelt, who was a flier, was shot down. And his dad of course was absolutely devastated, never really recovered, and died about a year after it happened.

LHL: We’re now talking about those characters in the book who, from our point of view, might be considered the villains of the tale. Among them is a man named George Creel. The government set up a propaganda machine to actually distribute hate speech.

AH: Creel, a journalist who was a friend and supporter of Wilson, was given a huge budget to set up an agency that poured forth propaganda in every conceivable means—films, books, pamphlets, posters supporting the war effort—and painting it as a high-form noble cause. Creel’s agency ran something that became known as the “Four-Minute Men,” who were speakers who were trained to give speeches that lasted no more than four minutes. They popped up in all kinds of places, rode around to Kiwanis clubs and church gatherings.

They were most famous for appearing in movie houses, because in those days the movies were on reels [and] didn’t go very long. I don’t know how long a silent-film reel lasted, but probably not more than twenty minutes or so. If you were a small movie house and just had one projector, you had to pause while a projectionist changed the reel of the film. Normally during that time they would show slides on the screen of advertisements for local merchants and so on. But instead, starting soon after the U.S. entered the war, up would come this slide that said, stand by for a representative from the u.s. government, and one of these so-called Four-Minute Men—and indeed they were all men—would pop up on the stage and give a patriotic speech about our advances on the battlefield or the duty of all citizens to contribute to the war effort or whatever. They had Four-Minute Men who spoke many different languages, so they could address ethnic gatherings. They had what they called “Colored Four-Minute Men,” who spoke to Black audiences. So this kind of drumbeat patriotism just pervaded American life during this period.

What was particularly interesting to me is it continued after the war was over. For example, within two months after the U.S. entered the war they started press censorship on a large scale, and that was put in the hands of one of these conservative white Southerners in Wilson’s cabinet, Albert Burleson, who was a former congressman from Texas, an arch-segregationist. At the time that he was born, his family owned twenty slaves. He, as postmaster general, was given the authority under the law to declare a newspaper or magazine or newsletter unsalable, which meant it couldn’t go through the mail. Now, this didn’t affect mainstream daily newspapers, but any weekly or monthly or journal of opinion, or something like Lapham’s Quarterly if it had been around then, had to travel through the mail to reach its subscribers. There was of course no internet at that time, no radio or TV, and the censorship started during the time that the U.S. was in the war. But it continued for more than two years after the war ended in November 1918.

Burleson loved censoring, and by the time he left office at the end of the second Wilson administration, he had forced seventy newspapers and magazines out of business and had banned specific issues of hundreds more. So this thing that was ostensibly started because the United States was at war continued after that—and the same thing for many other forms of repression in this period as well.

LHL: And also what happens is a shift from the hate speech being directed at Germans, all things German being evil, which is the original pitch of the Creel Protective League. And then they shifted to communists, Bolsheviks. The Hun Scare turns into the Red Scare during these same four years. In other words, the punishment of foreigners for being foreigners, the German language forbidden to be spoken in the United States, music of Beethoven not allowed to be played.

AH: That’s right. It started off, as you say, as anti-German hysteria because we were at war with Germany, and it reached considerable extremes. Several states passed specific laws against speaking German in public or on the telephone. There were bonfires of German books, German-language books, dozens of them around the country. It wasn’t until I started writing this book, American Midnight, that I realized some of the names that I was familiar with when I was growing up had been changed during this era. For example, I grew up in Manhattan and when hospitalized once was at Lenox Hill Hospital, which I believe it is still called today, but it had originally been the German Hospital and Dispensary with a Kaiser Wilhelm Pavilion, and that name was hastily changed when the United States went to war. All kinds of other name changes took place during this period. The frankfurter became the hot dog and so on.

Then, as you said, the Russian Revolution happened in November of 1917, and that added to the hysteria, because then the person speaking a foreign language on the street corner might not only be a German spy but maybe a Russian spy as well. Then, after the war ended, the hysteria grew even more intense again, directed at leftists, anarchists, communists of all sorts, and people who might be their sympathizers.

There were many, many Americans who were sentenced to prison for opposing the war, and dozens of them were still in prison long after the war ended—Eugene Debs, for example, the perennial socialist candidate for president, who was a very peaceful man, deeply committed to the electoral process. He won 6 percent of the popular vote for president in 1912. For an antiwar speech he gave in 1918 questioning the war, he was sentenced to ten years in prison, and he was still in prison a couple of years after the war ended. As a prisoner in the federal penitentiary in Atlanta in November 1918, he received nearly a million votes for president. One of the appalling statistics that I learned in the course of writing American Midnight was that during those four years, 1917 to 1921, roughly a thousand Americans spent a year or more in prison, and a much larger number [spent] shorter periods of time in prison solely for things that they wrote or said. And I think it was the greatest assault on civil liberties since the end of slavery.

LHL: Talk about the man who made a movie about the Revolutionary War and was sent to prison for offending our British ally.

AH: This was a filmmaker who made a silent film, a real big-budget extravaganza, called The Spirit of ’76. In our national mythology of the Revolutionary War, the British are the bad guys, right? So in his film, which had started production before the U.S. entered the war, they made fun of King George III. They showed a British mercenary bayoneting a child and so forth. But when the film was released in the fall of 1917, the Brits were our allies. And this poor filmmaker was sentenced to three years in prison, almost all of which he served at the McNeil Island penitentiary in Washington. So the man’s life was ruined for making a film that followed the mythology about the American Revolution as it was before this period and it was after this period. But during this period you couldn’t say anything nasty about our noble ally Great Britain. The judge and jury were quick to send him to prison. This was one of countless cases that really reflected a mood of hysteria that I think has been only very rarely seen in this country, although, of course, we’ve seen signs of it recently as well.

LHL: Yeah, we are. It’s one of the reasons I think this book is such an important book, because to read so many similarities between what’s going on in 1917–1921 and almost exactly a hundred years later between 2017 and 2022—you find a lot of this anger, violence, and self-defeating destruction of democracy.

AH: I think of this 1917 to 1921 period as being the most Trumpian period of American life before Trump, because you had, you know, great hysteria against immigrants and refugees, and you had a lot of things happening that Trump would have liked to do, like censoring the press. Trump would have loved nothing better than to close down dissenting media. He wasn’t able to do it. He would have liked to do nothing better than throw his opponents in prison. At Trump rallies in 2016, they were chanting, “Lock her up, lock her up,” about Hillary Clinton, and Wilson and the people who worked for him did lock all these people up. So I do see some eerie parallels there.

LHL: One more villain in the tale, and then we’ll talk about two heroes of the tale: Leonard Wood.

AH: Leonard Wood was the U.S. Army general, a close friend of Theodore Roosevelt who had won the Congressional Medal of Honor by being a key figure in the capture of the Native American rebel Geronimo. And then he had fought in the Philippine War, which was a very nasty war that too few Americans know about, 1899 to 1902, where the U.S. brutally suppressed, at the cost of hundreds of thousands of lives, Filipinos who didn’t want to become an American colony. Sporadic fighting there continued for some years after that. Wood was a veteran of those conflicts. And then in 1919 he was actually, right up until the summer of 1920, the leading Republican candidate for president. What’s eerie and interesting to me—and was a strong echo of this Trump period we just lived through and, heaven help us, go into some version of again—is that up to the last minute the leading candidates for president on both the Republican side and the Democratic side in 1920 were people who were campaigning on platforms of mass deportation.

General Wood was promising to deport people by the tens of thousands, deporting troublemakers of all kinds if he was elected president, and the man who looked as if he was going to be the Democratic candidate, A. Mitchell Palmer, the attorney general, was also promising shipload after shipload of troublemakers will be shipped away from American shores. So both these guys were running for president on the platform of mass deportations. Both of them went into the conventions in the summer of 1920 as the favorites. Happily, neither of them got the nomination.

LHL: Tell a couple of stories, Adam, about the heroes of the tale and individuals who resisted the war hysteria, who stood up for the principle of free speech, who risked prison to speak truth to power.

AH: You know, when I try to bring a piece of history like this alive, I do like to look for the good folks as well as the villains of the tale, and there are plenty of them. Emma Goldman, long-term charismatic anarchist speaker who really had very wide-ranging catholic with a small c interests. She was interested in modern literature and art and the liberation of women, and she very strongly opposed the war from the start, spoke out against the draft because this was the first time since the Civil War the United States had tried conscription. She was swiftly put on trial for that, found guilty, sentenced to two years in prison. And at her trial, she gave the most wonderful speech where she said, “Gentlemen of the jury”—you know, in those days, juries were all men, no women—we respect your patriotism, but may there not be two kinds of patriotism? Our kind of patriotism is that of a man”—I’m quoting from memory here, but I think it’s “a man who loves a woman with open arms. She is enchanted by her beauty, but he sees her faults. That’s how we feel about the United States.” A lovely, noble speech that ought to be right up there in the annals of great things Americans have said.

She was sent to prison for two years and, after she got out, was deported, never allowed to live in the U.S. again. So she’s one of my heroines, as is a woman named Kate Richards O’Hare, who was the leading orator in the Socialist Party, also sent to prison for opposing the war, and found herself in the women’s penitentiary in Jefferson City, Missouri, in the cell next to Emma Goldman. And the two women became great friends. Each of them wrote their recollections of the other. It’s lovely when you’re putting a book together and two of your characters knew each other and wrote or said things about the other to have that kind of raw material.

A third hero of the story, also a woman, is a doctor in Portland, Oregon, named Marie Equi. Very outspoken opponent of the war and of censorship who was quite imaginative. For example, every time she tried to give a speech, an antiwar speech in downtown Portland, the police would stop her. She realized there was one place where they couldn’t reach her. She borrowed the crampons of a telephone lineman, climbed to the top of the telephone pole, and operated from there as a crowd gathered. Only when she came down was she arrested. She, too, was sent to prison.

I’ll tell you about one more hero of the story. I had mentioned the attorney general Palmer and his plans to deport large numbers of people from the country. To do this, he staged the notorious Palmer Raids in late 1919 and early 1920, where roughly ten thousand people were arrested, questioned, often roughed up, and several thousand of them—we don’t know the exact number because this was taking place in more than two dozen cities—were held in prisons as candidates for deportation because you could be deported if the government considered you a troublemaker. And there was a very wide definition of that if you were not an American citizen. This was a time when a lot of people, you know, they’d been in this country for years, but they’d never bothered to formally get naturalized as American citizens because it didn’t seem to be necessary, or there was too much bureaucracy, or they didn’t speak English well. So Palmer had all these people rounded up in prison, and he was planning to deport them—and actually gave a speech boasting about how ship after ship would be going down through New York Harbor, taking all these people overseas forever.

But his plans were almost entirely foiled by a very brave bureaucrat named Louis Post, who was acting secretary of labor. Post had been a progressive journalist before the Wilson administration, had been the number-three person in the Labor Department. The secretary of labor was on sick leave. The fellow who normally would have taken his place had just resigned to run for Congress. Post became acting secretary of labor. And even though it was Palmer’s Justice Department who was arresting all these people, the Labor Department had authority over deportations because it controlled the Immigration Bureau. Post was a staunch civil libertarian. He was not a socialist or an anarchist, but he believed that nobody should be deported from the United States because of their political opinions. So he invalidated thousands of arrest warrants, released people from prison, and because of that totally foiled Palmer’s plans. Palmer was absolutely furious, as was the real architect of the Palmer Raids, somebody we Americans would get to know much better, twenty-four-year-old J. Edgar Hoover. They tried to get Post fired. They tried to get him impeached by Congress. They got the American Legion to demand his firing. But Post triumphed and remained in office until the very last day of the Wilson administration. He was an extremely skillful bureaucratic maneuverer as well as a passionate civil libertarian, an unusual combination. So he’s one of my favorite heroes in the book.

LHL: Mention one more: one of my favorite heroes, who’s the senator from Wisconsin.

AH: I follow Robert La Follette, Fighting Bob, as he was called, the shortest man in the U.S. Senate, which he made up for by having an enormous head of hair, sort of combed back and a big forelock, who all his life had been a very strong progressive voice for women’s rights, for the rights of people of all colors and ethnicities, for regulating business, I think certainly the leading elected politician of the progressive movement of that time. He was one of six senators who voted against the declaration of war in 1917. Wilson had said the war was “to make the world safe for democracy.” La Follette said, “So if we’re going to war to make the world safe for democracy, why aren’t we demanding self-determination for Ireland, for Egypt, for India?” which were at that time, of course, colonies of our ally Great Britain. La Follette was spurned for his stance about the war. All but two members of the faculty of his alma mater, the University of Wisconsin, voted to condemn him. He was hanged in effigy on the university campus, kicked out of a club he belonged to in Madison, Wisconsin. The Senate started an investigation about whether he should be expelled from the U.S. Senate. He was given a terrible time, but he stuck up for his principles. He was one of six senators who voted against the war. Fifteen members of the House of Representatives voted against the war, but their voices were drowned out in this patriotic hysteria.

LHL: This is a splendid book. What can we learn from it? I mean, what can we learn about the hydra-headed crises that confront America today in the year 2022? What can we learn from having survived the period 1917 to 1921?

AH: That’s the big question. I think if there was one thing that I would want people to take away from American Midnight, it’s the idea that democracy, despite all the different checks and balances and the separation of powers and whatnot written into our Constitution more than two hundred years ago, is fragile. It can easily be shattered and broken. It can easily be threatened. We’ve been reminded of that very recently by, for example, the assault on the Capitol on January 6 of last year. And in this period, 1917 to 1921, I really think a lot of the basic democratic freedoms that we take for granted in this country we lost during that period.

I think if there’s one other lesson that I wish people would take from the book, it’s that you don’t have to be a loudmouthed showman to be a demagogue and preside over this repression. Woodrow Wilson was the most dignified, professorial, genteel of American presidents, but he saw to the jailing of his opponents. He ordered press censorship. He seemed to show no concern whatever about the suppression of civil liberties during this period. So democracy’s a great thing, but it’s fragile. It can be threatened from all sorts of unpredicted and unpredictable sources. And we should always be on guard.

Thanks to our generous donors. Lead support for this podcast has been provided by Elizabeth “Lisette” Prince. Additional support was provided by James J. “Jimmy” Coleman Jr.

Subscribe to The World in Time on iTunes, Spotify, Stitcher, SoundCloud, and Google Play, as well as via RSS.