The Northampton Election, December 6, 1830, by J.M.W. Turner, c. 1830. Photograph © Tate (CC-BY-NC-ND 3.0).

During the 2020 U.S. presidential election season, we will feature voices from the past who told stories that rhyme with the one unfolding before us—stories of those who got out the vote, narrated trips to the polls, tested the limits of their political power, cheated their way to an electoral victory, or were prevented from exercising any of theses democratic roles by the actions of their leaders or neighbors.

Only in the past two centuries has voting become a private act. Growing concern over voter intimidation, retribution, and blackmail led to the institution of secret ballots in democracies around the world during the nineteenth century. Before the Ballot Act of 1872 made the secret ballot part of the voting experience of all eligible voters in Britain—barely more than a fifth of the nation’s adult male population—many pundits strongly argued against it. John Stuart Mill was skeptical of the benefit of such a system, writing in 1861, “People will give dishonest or mean votes from lucre, from malice, from pique, from personal rivalry, even from the interests or prejudices of class or sect, more readily in secret than in public.” Sydney Smith’s 1839 treatise Ballot summarizes the typical objections. Smith, an Anglican cleric, got his start in public intellectualism after founding the Edinburgh Review in 1802. He became known in London high society for his lectures and witty prose—which usually leaned conservative—and his career in the church was buoyed by his many friends in high places. In 1831 he was appointed residentiary canon of St. Paul’s Cathedral in London, never ascending any higher in the church, perhaps for being a joker amid a staid Tory lot. “He had now made up his mind that he was unequal to a bishopric,” the historian Leslie Stephen wrote in 1897, “but, as his daughter tells us, he was deeply hurt that his friends never gave him the opportunity of refusing one.” Instead he continued to find fame as an author and one of the great letter writers.

The Reform Act of 1832 had nearly doubled the number of eligible voters and eliminated some corrupt boroughs where a handful of voters selected multiple MPs. Other radical changes to elections seemed possible, and aristocrats worried that electoral reform would damage their political influence; Smith wrote Ballot during this time. As scholar Bruce L. Kinzer wrote in his 1978 article “The Un-Englishness of the Secret Ballot,” those against the secret ballot often condemned it for feeling squeamishly foreign:

Objection to the ballot as un-English stemmed from the conviction that secret voting was inconsistent with the character and habits of Englishmen. A system of secret voting might suit a nation whose people were hypocritical, cunning, furtive, and deceitful (i.e., the French, who had experimented with secret voting during the 1790s and made it an integral part of their electoral machinery in the first half of the nineteenth century), but it had no place in a country like England, whose people—noted for their independence, manliness, honesty, and frankness—always preferred to conduct their affairs in the open and in the light of day. Very few English tenants, tradesmen, or workmen, it was held, would lie when asked by their landlords, customers, or employers for whom they intended to vote, as deception was basically foreign to the English nature. Thus, for the most part, the ballot would fail to provide protection for those supposedly requiring it. But the danger remained, many insisted, that the introduction and use of secret voting might, over a period of time, inculcate habits of falsehood and deception which would have a most pernicious effect on the morality of the nation as a whole.

Despite these objections, the secret ballot soon became standard—although, like many electoral reforms, it took advocates decades to see their mission realized. It was implemented first in Australia in the 1850s (hence the secret ballot sometimes being called the Australian ballot), then finally in Britain in 1872, and in the United States in the 1890s.

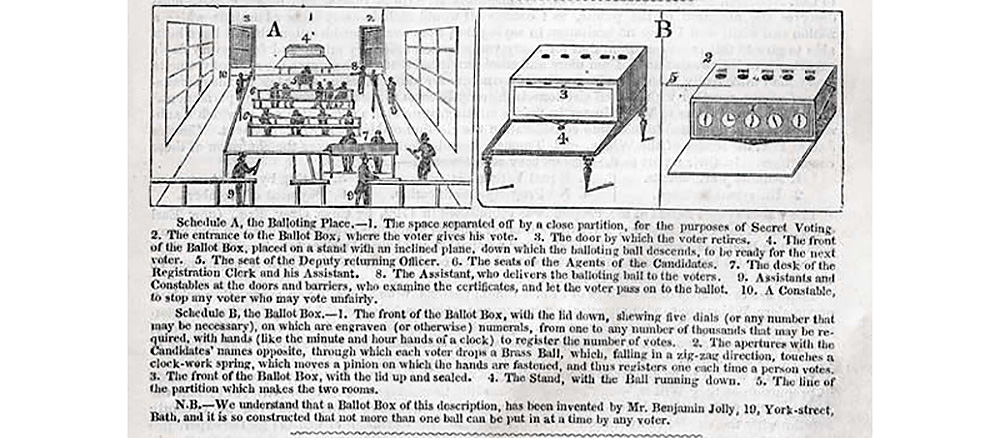

It is possible, and perhaps not very difficult, to invent a machine by the aid of which electors may vote for a candidate without its being discovered for whom they vote: it is less easy than the rabid and foaming Radical supposes; but I have no doubt it may be accomplished. In the dagger ballot box, which has been carried round the country by eminent patriots, you stab the card of your favorite candidate with a dagger. I have seen another, called the mousetrap ballot box, in which you poke your finger into the trap of the member you prefer, and are caught and detained till the trap clerk below (who knows by means of a wire when you are caught) marks your vote, pulls the liberator, and releases you. Which may be the most eligible of these two methods I do not pretend to determine; but, by some means or another, I have no doubt the thing may be done.

If a man is sheltered from intimidation, is it at all clear that he would vote from any better motive than intimidation? If you make so tremendous an experiment, are you sure of attaining your object? The landlord has perhaps said a cross word to the tenant; the candidate for whom the tenant votes in opposition to his landlord has taken his second son for a footman, or his father knew the candidate’s grandfather: How many thousand votes, sheltered (as the ballotists suppose) from intimidation, would be given from such silly motives as these? How many would be given from the mere discontent of inferiority? Or from that strange simious schoolboy passion of giving pain to others, even when the author cannot be found out?—motives as pernicious as any which could proceed from intimidation. So that all voters screened by ballot would not be screened for any public good.

An abominable tyranny exercised by the ballot is that it compels those persons to conceal their votes who hate all concealment and who glory in the cause they support. If you are afraid to go in at the front door and to say in a clear voice what you have to say, go in at the back door, and say it in a whisper—but this is not enough for you; you make me, who am bold and honest, sneak in at the back door as well as yourself; you compel me to hide the best feelings of my heart and to lower myself down to your mean morals. It is as if a few cowards, who could only fight behind walls and houses, were to prevent the whole regiment from showing a bold front in the field. What right has the coward to degrade me who am no coward, and put me in the same shameful predicament with himself?

To institute ballot is to apply a very dangerous innovation to a temporary evil; for it is seldom, but in very excited times, that these acts of power are complained of which the ballot is intended to remedy. There never was an instance in this country where parties were so nearly balanced; but all this will pass away, and, in a very few years, either Peel will swallow Lord John, or Lord John will pasture upon Peel; parties will coalesce, the Duke of Wellington and Viscount Melbourne meet at the same board, and the lion lie down with the lamb. In the meantime a serious and dangerous political change is resorted to for the cure of a temporary evil, and we may be cursed with ballot when we do not want it and cannot get rid of it.

If there is ballot there can be no scrutiny, the controlling power of Parliament is lost, and the members are entirely in the hands of returning officers.

What a flood of deceit and villainy comes in with ballot! In the open voting, the law leaves you fairly to choose between the dangers of giving an honest or the convenience of giving a dishonest vote; but the ballot law opens a booth and asylum for fraud, calling upon all men to lie by beat of drum, forbidding open honesty, promising impunity for the most scandalous deceit, and encouraging men to take no other view of virtue than whether it pays or does not pay.

If ballot were established, it would be received by the upper classes with the greatest possible suspicion, and every effort would be made to counteract it and to get rid of it. Against those attacks the inferior orders would naturally wish to strengthen themselves, and the obvious means would be by extending the number of voters; and so comes on universal suffrage. The ballot would fail: it would be found neither to prevent intimidation nor bribery. Universal suffrage would cure both, as a teaspoonful of prussic acid is a certain cure for the most formidable diseases; but universal suffrage would in all probability be the next step.

It is hardly necessary to say anything about universal suffrage, as there is no act of folly or madness which it may not in the beginning produce. There would be the greatest risk that the monarchy, as at present constituted, the funded debt, the established church, titles, and hereditary peerage, would give way before it. Many really honest men may wish for these changes; I know, or at least believe, that wheat and barley would grow if there was no Archbishop of Canterbury, and domestic fowls would breed if our Viscount Melbourne was again called Mr. Lamb; but they have stronger nerves than I have who would venture to bring these changes about. So few nations have been free, it is so difficult to guard freedom from kings, and mobs, and patriotic gentlemen; and we are in such a very tolerable state of happiness in England that I think such changes would be very rash; and I have an utter mistrust in the sagacity and penetration of political reasoners who pretend to foresee all the consequences to which they would give birth. When I speak of the tolerable state of happiness in which we live in England, I do not speak merely of nobles, squires, and canons of St. Paul's, but of drivers of coaches, clerks in offices, carpenters, blacksmiths, butchers, and bakers, and most men who do not marry upon nothing, and become burdened with large families before they have arrived at years of maturity. The earth is not sufficiently fertile for this: Difficilem victum fundit durissima tellus [They did not understand the difficult art of sweet liberty].

The great art in politics and war is to choose a good position for making a stand. The people seem to be hurrying on through all the well-known steps to anarchy; they must be stopped at some pass or another: the first is the best and the most easily defended. The people have a right to ballot or to anything else which will make them happy; and they have a right to nothing which will make them unhappy. They are the best judges of their immediate gratifications, and the worst judges of what would best conduce to their interests for a series of years. Most earnestly and conscientiously wishing their good, I say,

No Ballot.

Read the other entries in the series: Andrew Dickson White, John Milton, Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, George O. Dunnell, and Rutherford B. Hayes.