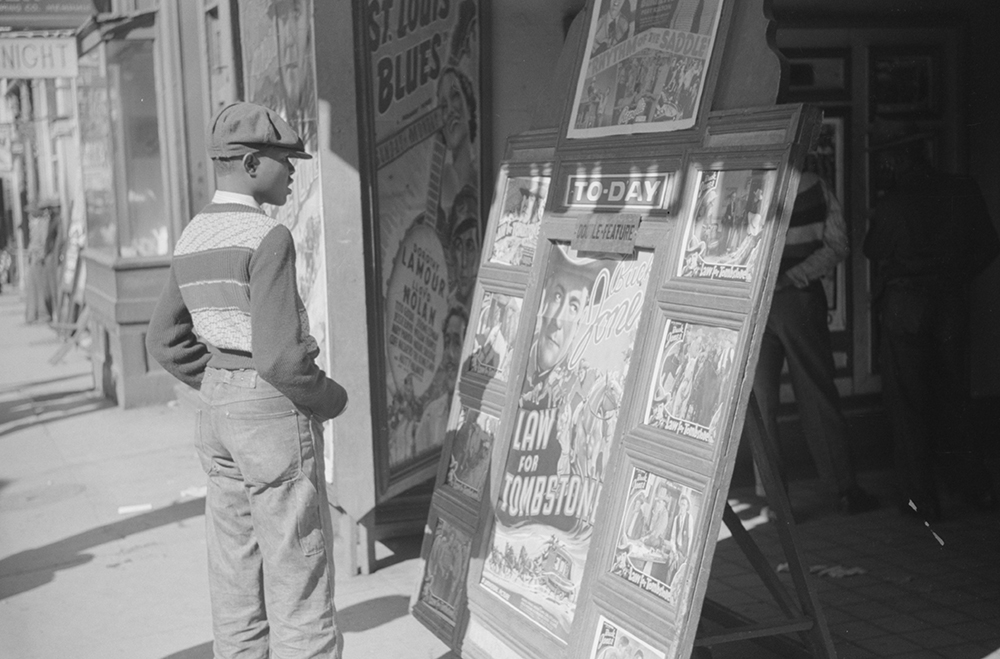

Liberty Theater in New Orleans, c. 1935. Photograph by Walker Evans. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

Even in the middle of the Great Depression, optimism bubbled up in parts of America as Franklin D. Roosevelt took office and started implementing the New Deal in 1933. Hollywood took notice. The movie industry was eager to attach itself to the president’s hopeful messaging; Warner Brothers executives Harry and Jack Warner were two of Roosevelt’s most prominent fundraisers. All this hope was a bit of theater, however, meant to help to get butts in theater seats while obscuring the labor discontent that was brewing within Hollywood, just as it was elsewhere. And that fury was about to spill over.

The Screen Actors Guild (SAG) formed that year, 1933. There was already an actors’ union, the New York City–based Actors’ Equity Association, but it was focused on theater actors; its leaders reportedly saw film acting as less serious than stage work and were irritated by the growing number of stage actors being poached by Hollywood in the sound era. Equity—which may have been cowed by an unsuccessful strike it had organized in 1929, just before the Great Depression started—wasn’t intervening in screen actors’ disputes with producers in Hollywood. That opened up room for another union in town, one that sought to build its membership from the screen actors being exploited on lots in Southern California.

The previous decade had been rough for most Hollywood actors, whose grievances and the studios’ inadequate response to them laid the groundwork for SAG’s big plans to unionize. Actors at all levels realized that despite the mythologized power of the star system, they had very little sway over producers and studios, which set work conditions. Stage actor Wedgwood Nowell wrote in a letter to Equity in 1924, “It is reasonably certain that a ‘salary list’ is being kept on file [by the producers] with a view to preventing actors from raising their salaries between pictures when freelancing.” This collusion between producers was seemingly intended to keep down the salaries of midrange actors not tied to any long-term contracts, explained historian Sean Holmes in an article in Film History.

It wasn’t just money that led to discontent. Dutch actress Jetta Goudal became fed up with how commodified and sexualized she was by Paramount and, later, the Cecil B. DeMille Pictures Corporation, so she attempted to wrest control of her own image away from them. She was painted as a prima donna, and DeMille terminated her five-year contract with three years remaining, insisting she was a “little cocktail of temperament.” Goudal sued DeMille for breach of contract and won. “Goudal’s victory was a hollow one, though,” Holmes wrote. “According to press reports, the studios responded by placing her on an unofficial blacklist, and she found it impossible to find work.” She became an interior designer.

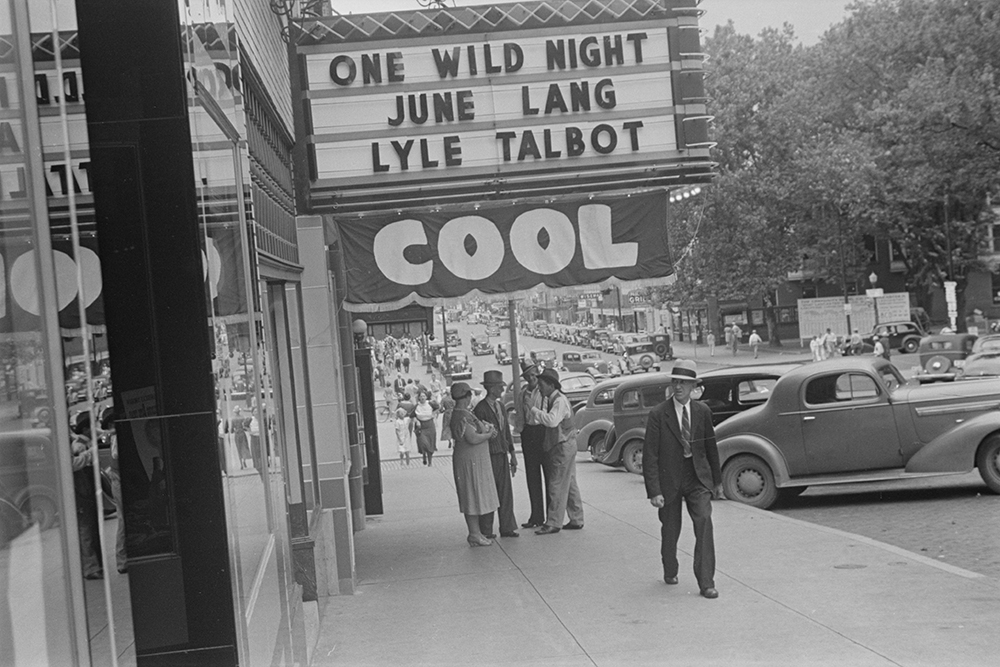

At the same time, the studios were buckling under the Depression. Theaters were closed, jobs were lost, and people simply didn’t see going to the movies as a valuable pastime—how could they justify the expense? Producers were unwilling to take any cuts themselves to ease the financial pressure on the industry. Louis B. Mayer, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer’s chief, received a salary and bonuses in the mid-1930s totaling around $1,300,000 per year (worth about $23 million today), making him the highest-paid man in the United States, a distinction he held until 1950. And so the producers looked elsewhere for savings, threatening to close the studios altogether unless all employees agreed to a 50 percent pay cut for two months and a new Code of Fair Competition that imposed revised and severe contractual limitations, including a salary cap for actors. While wages were in danger, working conditions remained miserable. When Judy Garland worked as an extra during the late 1930s, producers gave her amphetamine uppers to keep up her energy. She then would fall asleep thanks to sleeping pills (also supplied by producers), and “after four hours they’d wake us up and give us the pep pills again so we could work seventy-two hours in a row,” she told biographer Paul Donnelley.

With actors’ complaints and evidence of bad employer behavior in hand, SAG filed for incorporation on June 30, 1933. That moment came only after dramatic organizing worthy of the industry. The actor Robert Young, an early SAG member best known for playing the father in Father Knows Best, said, “The average person like myself, under contract to a studio, with a family, was extremely scared. We showed great bravery in those early days…It was one of those things where our belief in the cause overcame our fear of the consequences.” The married actors Kenneth Thomson and Alden Gay held late-night meetings in their basement in Los Feliz to discuss plans to unionize. Secrecy was key: Sara Karloff, Boris’ daughter, said her father would carry around a roll of dimes so he could conduct union business over pay phones. Karloff, who was then only two years removed from grueling workdays on Frankenstein, held a secret meeting in his garage, brainstorming the language of SAG’s charter with seventeen other actors. He became SAG member number nine (his longtime collaborator/competitor Bela Lugosi was member number twenty-eight) and remained intimately involved with the union as a board officer until 1951. In a 1960 column in Screen Actor, Karloff wrote, “The general idea was to set the skeleton of an organization for film actors with a constitution and the machinery for making it work, but in the meantime sit back and hold the fort and wait for the producers to make the inevitable boo-boo that would enable us to interest the stars, without whose support we knew the Guild could not hope to function successfully.”

SAG membership grew steadily throughout the 1930s, even as it remained unrecognized as a bargaining agent. Equity was wary of SAG as a rising organization, concerned about protecting its own interests and its power to bargain; it was not lost on anyone how tenuous and precarious both unions were. Unlike SAG, Equity prohibited Black actors from joining, which deepened the divide between the unions—though SAG, too, struggled to build Black membership. The Negro Actors Guild of America formed in New York City in 1936 with the goal of creating more acting opportunities for Black actors in film and theater and making those roles more realistic. It was created in part as a response to the Hollywood-based unions’ lack of interest in fully integrating Black talent into their definition of solidarity. Equity failed to hold on to its control in New York in large part because it refused membership to Black actors, which further weakened its position in Hollywood. Soon enough, with no claim at all to universal representation, Equity surrendered its film jurisdiction to SAG.

Yet even without competition from Equity, SAG found it difficult to gain momentum while dealing with the industry- and society-wide impacts of the Depression. Little was achieved for years, despite clandestine meetings and organizing, and by the start of 1937 SAG still hadn’t succeeded in being recognized by the studios. The mob didn’t help matters. William Morris Bioff was a massively powerful Hollywood business agent and representative for the mob-controlled International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees (IATSE), with ties to Chicago gangster Frank Nitti. Bioff seemingly took full advantage of his mob connections in representing the stagehands’ and projectionists’ unions, particularly by threatening mass work stoppages unless paid off personally in cash. Earlier in the 1930s he had worked as an enforcer for the mob-adjacent union leader George Brown, president of the IATSE; he moved up through extortion, and became a big enough union figure to intimidate movie studios into handing over millions of dollars. This direct relationship between Hollywood unions and the Mafia kept the studios from formally recognizing the unions.

But SAG members had had enough. They voted to go on strike at midnight on May 10, 1937, unless the Guild was recognized, allowing it to negotiate with management on behalf of its members.

In the yearslong fight for recognition, SAG president Eddie Cantor had appealed to President Roosevelt, who issued an executive order in November 1933—as part of his enforcement of the newly passed National Industrial Recovery Act—to suspend the pay cuts and contract limits that producers had slipped into their Code of Fair Competition, which workers in Hollywood had been vociferously protesting. Irving Thalberg, the “Boy Wonder” producer responsible for hits such as Mutiny on the Bounty (1935) and A Night at the Opera (1935), was livid at the prospect of unions gaining power in Hollywood, saying he would die before he’d recognize SAG. Thalberg died of pneumonia at the age of thirty-seven in September 1936. Former SAG national executive director Ken Orsatti later wrote that “in 1936, Thalberg died and in 1937, the studios accepted defeat and signed a contract with the Guild that, for the first time in Hollywood, gave actors a sense of empowerment.”

On May 9 the studios, still under financial pressure, finally relented. After a showdown at Louis B. Mayer’s beach house, the MGM chief and Twentieth Century-Fox head Joseph Schenck agreed to minimum salaries ($25 a day for actors, $35 a day for stuntmen, and $5.50 a day for extras) and rules on overtime, continuous employment, and other issues of overwork. It was a big win, especially during the Depression. On May 10 over four hundred actors lined up for their union cards outside SAG’s headquarters on the Sunset Strip, including Barbara Stanwyck and Greta Garbo. For a moment, the only thing on anyone’s mind in Hollywood was solidarity.

SAG wasn’t alone in fighting for rights in the film industry during the Depression. The Screenwriters Guild, originally a social club, was waging its own war: even after the National Labor Relations Board certified the Guild as the bargaining agent for most writers in 1938, the producers didn’t recognize it until the following March. What bound the guilds together was a growing understanding of themselves as workers. This awakening was of course due to their realization of their own exploitation. In his 2016 article “The Other Good Fight: Hollywood Talent and the Working-Class Movement of the 1930s,” scholar Michael Dennis wrote, “Out of the alchemy of economic upheaval, political ferment, and professional self-interest, the progressive element in Hollywood’s creative class fashioned a worldview that placed the emancipation of labor at its center.” Celebrity actors, desperate extras, and many others were aligned, to some extent, in their experience of abuse and the hope for a better future achieved via unity.

Equity, too, had begun with a gradual epiphany over mistreatment. Previous attempts at unionization in the stage world, such as the Actors’ Protective Union in the 1860s, were relatively powerless. Before the formation of Equity, actors were never paid for rehearsals, which could go on for months, and were often discharged without notice. It was a turbulent, uncontrolled profession, until 112 actors met in May 1913 to discuss what it would take to form an effective union. By 1919 they remained unrecognized and decided to strike, closing thirty-seven plays in the process. The strike lasted about two months, ending with a five-year contract that phased in provisions such as guaranteed salaries; restrictions on foreign actors, ostensibly to protect jobs for American actors; and finally, in 1933, a minimum-wage guarantee for stage actors.

As in other professions, employers in Hollywood routinely found new ways to exploit and mistreat workers at all levels through each unionized era, making concessions only when forced. No one union could complete the work of fair and equitable treatment, especially with different unions representing various crafts (actors, writers, directors, stagehands, editors, and so on), all with common but also separate interests, so subsequent groups would take up the task, with varying degrees of success.

The Screen Actors Guild, like all unions at the time, struggled throughout the late 1930s, in part because the studios continued their reign as oligopolies—indeed, the frustration became more palpable as the studios flourished while actors and other screen workers did not. Through vertical integration and other strategies, the major studios had an iron grip over the movie industry, its workers, and its cultural impact. In City of Nets: A Portrait of Hollywood in the 1940s, writer and editor Otto Friedrich wondered whether Hollywood’s success in the late 1930s resulted from the power wielded by producers or perhaps because movies offered an escape from real life’s difficulties. But then he posed another possibility: “Or perhaps it was simply because the studios had gradually established what amounted to an illegal cartel, controlling both their actors and writers at one end of the process and their distributors and exhibitors at the other end. They couldn’t lose.”

Both the film industry and the Hollywood unions faced a number of further challenges in the 1940s. The introduction of television caused another rift between SAG and Equity; even after they agreed in 1940 to share jurisdiction over TV actors, it remained a contentious question for many years. Fears over communism, particularly after World War II, hit Hollywood hard, and Ronald Reagan, who served as SAG’s president from 1947 to 1952, cooperated with the House Committee on Un-American Activities (HUAC) and named names. Many in Hollywood, including more than a hundred SAG members, were blacklisted. A few politicians even suggested union membership was evidence of communist sympathies, an opportunistic attempt to dilute union power.

By 1948, however, the landmark antitrust case United States v. Paramount Pictures, Inc. was being litigated, and Hollywood’s unions hoped for a court decision that would put an end to the traditional studio system once and for all. The government argued that the majors were monopolizing the moviegoing experience—studio-owned theaters, for example, would show only their own movies. The major Hollywood studios were charged with colluding in monopolistic dominance over production, distribution, and exhibition of movies. A temporary 1940 resolution made only minor changes to trade practices, but the Justice Department later determined that the studios were not complying with it properly and reopened the case. It languished for years, with a decision in favor of the Justice Department in 1945 that was appealed to the Supreme Court, which upheld it in May 1948. Production was effectively severed from exhibition, paving the way for new industry leaders and abolishing the practice of block-booking, which forced independent theater owners to take a great many films regardless of quality or demand.

At the same time as the studio system began its slow collapse, box-office numbers were falling and productions were plagued by political targeting and work stoppages. The Paramount antitrust case, while generally a success, did have at least one adverse effect on workers: non-famous actors were very rarely given contracts at all afterward, threatening the promise of steady employment in a new way. In 1947 18 percent of SAG actors were under contract; by the end of 1948, that number had fallen to 7 percent.

Yet during the 1930s and ’40s, solidarity between high-earning stars and poverty-stricken actors was crucial to the growth of the Hollywood unions. The studio system treated both groups as bodies to be placed in front of cameras and little more; contracts could, and were, renewed or canceled at the whim of producers. Olivia de Havilland is perhaps the most famous example of actors and unions pushing back in this period. Her Warner Brothers contract was supposed to end in 1943, but the studio tacked on an additional six months to cover the period she was suspended for refusing parts. Backed by SAG, she sued Warner Brothers on August 23 of that year, asking the court to enforce a state law that employees cannot be held to a contract for longer than seven years. She won in December 1944, which allowed her to work for other studios. The decision restricting contracts to seven calendar years became known as the De Havilland Law. In his article, Dennis quoted the Communist Party’s Daily Worker: “These stars recognized that unionization is the greatest protection workers can have, even such high-salaried workers as they are.” For decades all the glamour was a disguise for untold exploitation, and performers who believed they were artists and not workers were deluded. It took repeated reminders of their powerlessness to change the tide and create what Dennis called “a new working class.”