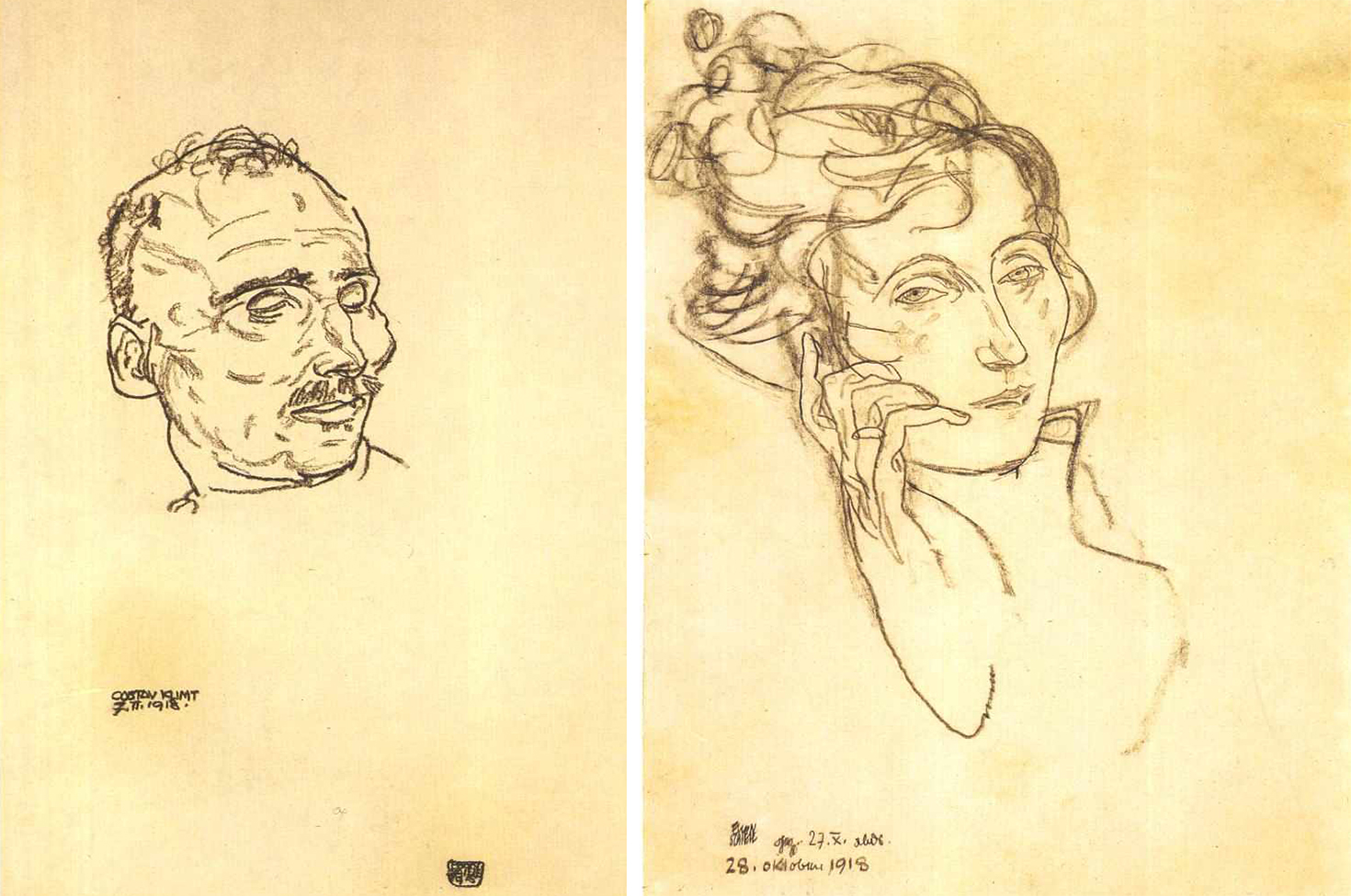

Left: Gustav Klimt, Dead in His Bed, by Egon Schiele, 1918. Right: Portrait of the Dying Edith Schiele, by Egon Schiele, 1918. Wikimedia Commons.

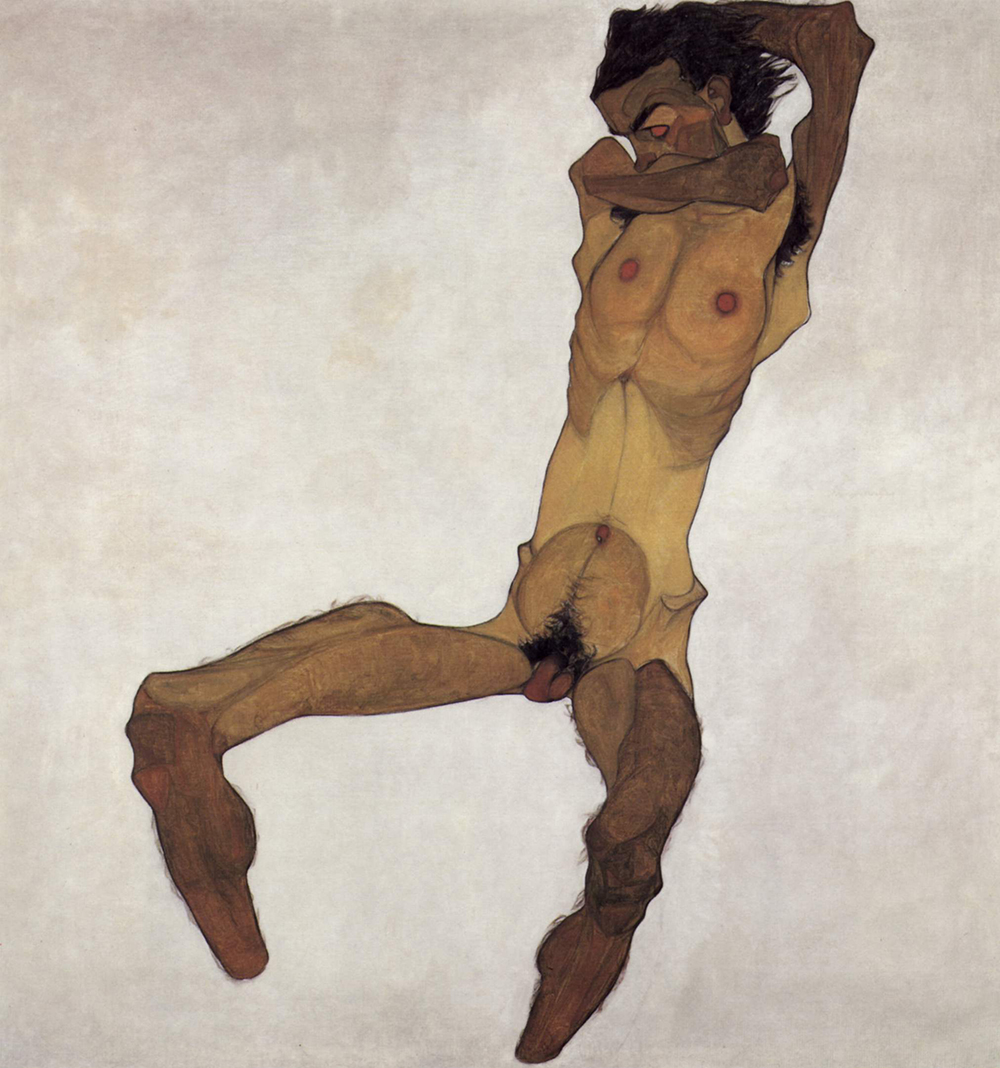

Let’s begin with Egon Schiele’s elbows: the Austrian artist’s swollen left elbow bent over his head in a gesture of support, the right drawn across his face, almost directly under his nose. Here, in his 1910 painting Seated Male Nude (Self-Portrait), rendered in muddy browns and sickly yellows, Schiele’s limbs look withered, his joints too pronounced. His elbows frame his face, drawing attention to one arched brow and a glowing reddish eye (a feature made even more striking by the repetition of its color and shape in nipples, genitals, and navel). Elbows direct arms that appear severed; his left hand disappears behind unruly hair, and his right arm seems to disintegrate below the joint. He looks close to what the art critic Julius Meier-Graefe described six years prior as the New Vienna, works of art that showed figures who were “shockingly thin, weak of bone and precociously diseased.”

Precocious is a fitting word for Schiele. In more romantic histories he is regarded as a wunderkind of sorts who emerged from the shadow of his mentor, Gustav Klimt—the most recognizable member of the Vienna Secession, a group of artists, designers, and architects bound together only by their rejection of the city’s traditional arts institutions—to produce transgressive self-portraits in which his body is rendered somewhere between the diseased and the obscene, only to die tragically young at the age of twenty-eight. Seated Male Nude (Self-Portrait) was a loud embrace of the New Vienna, a canvas that eclipsed Klimt’s elegantly patterned surfaces with mottled skin and pronounced hip bones. But for all of his self-portrait’s insistence on illness, Schiele was barely twenty years old when he produced the large canvas. He would make dozens of paintings like the 1910 self-portrait, works in which those same deformed limbs and overgrown joints, that same sickly skin, reappeared both on his own body and those of models and patrons.

Let’s return to those same elbows—to Egon Schiele’s elbows—captured not by Schiele but in a photograph taken by Martha Fein on October 31, 1918. If in his self-portrait eight years earlier Schiele performed emaciated illness, it was made real in Fein’s photograph. The challenging self-presentation of a young artist is, in the photograph, replaced with an eerie calm. Wrinkled bed linens and stacked pillows, a body laid out on a bed, flowers jutting into the foreground—these details announce the photograph’s purpose. This is Schiele on his deathbed, a casualty of the Spanish flu.

Schiele was one of millions worldwide who died in the pandemic’s second wave and one of the estimated 18,500 Austrians killed in 1918, a number that included both his pregnant wife, Edith Schiele (née Harms), and Klimt. He sketched them both on their deathbeds, two drawings in pen and ink striking in their similarity, immeasurable in their loss. That the human body contains histories seems obvious, especially to a keen student of portraiture like Schiele. Be it rendered in paint or captured by the camera or even in the labor of drawing, Schiele’s body carries with it echoes of the confluence of crises of 1918: war, food shortages, national decline, and of course disease. That’s equally true of his final portraits of Klimt and Edith, made into memory by his hand. Modernism, art historian T.J. Clark writes in Farewell to an Idea: Episodes from a History of Modernism, “turns on the possibility of transcendence.” In elbows bent, in small details of the body, history insistently demands to be acknowledged, overcrowding Schiele’s works with the contingency of 1918, a moment—perhaps a feeling—that seems particularly pressing. Taken together, details of limbs and joints, humble drawings, photographs, and scraps of paper accumulate to form an unwitting monument to immense loss.

Egon Schiele sat by Gustav Klimt and made three sketches of his mentor on his deathbed on February 6, 1918. Klimt died at the age of fifty-five, a foreshadowing of the overwhelming death that would reach Vienna months later. Earlier that winter, Klimt had had a stroke that partially paralyzed him. Sent first to a sanatorium and later, once he stabilized, to a Vienna hospital, Klimt was placed in a ward quickly overrun with the Spanish flu. His decline was swift.

Schiele’s sketches capture Klimt’s face from different angles, but in each his closed eyes appear hollow, his face heavily lined and shadowed. They are not tranquil, passive images of death. Instead tufts of Klimt’s thin hair compete with the insistent lines that form the features of his face; a slightly misshapen ear clashes with a sharp jawline. The drawings have a hint of chaos, a striking contrast to the still quiet of his death mask. But then chaos is what surrounded Klimt and Schiele in February. As Schiele reportedly sat silently, sketching at Klimt’s bedside, Vienna verged on anarchy.

Supplies to the city were limited. The war, now in its fourth year, had taken a toll on the Habsburg Empire, leaving its states to fight over increasingly limited resources. Coal, paper, and medicine were all hard to come by. But it was food, and the inability to provide Vienna’s citizens with it, that led to social unravel. As the Austro-Hungarian Empire slowly collapsed, “hunger, violence, and a deterioration of social norms left Vienna nearly ungovernable,” writes the historian Maureen Healy in Vienna and the Fall of the Habsburg Empire: Total War and Every Life in World War I. The Austrian prime minister had been assassinated in late 1916, and the parliament, only recently reconvened by the emperor after years of hiatus, tried to ease growing unrest by pardoning imprisoned political dissidents. But the gesture was largely futile—the government had already lost the trust and support of most of its citizens, who were hungry, desperate, and weary of a war that they had been promised would be quick and successful. Food was heavily rationed, and by 1918 some Austrian citizens were allowed to consume only 830 calories a day. A month before Klimt’s death, flour rations were cut in half. The decision drove workers to strike: in Vienna, an estimated 110,000 people, roughly one-third of the workforce, began putting down their work and walking away. The workers demanded food, they demanded an end to World War I. The strike ended a week before Klimt died. Food remained scarce.

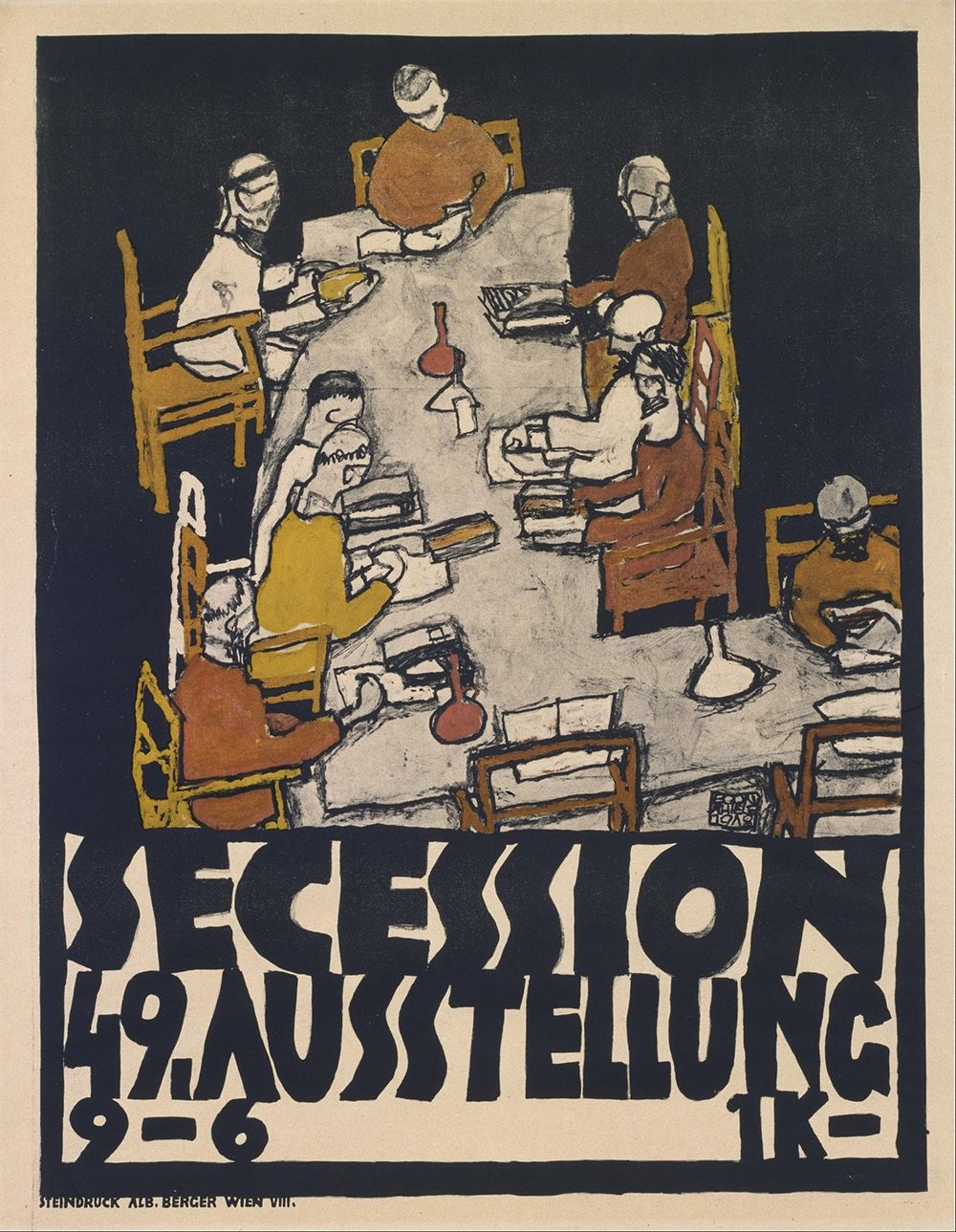

In Schiele’s last painting of Klimt, The Friends (Round Table), mentor and student and their elbows face off at an L-shaped table, surrounded by other artists, including Albert Paris Gütersloh and Anton Faistauer. Schiele sits at the head of the table, gobbling up the composition, his eyes staring down the table, his body pitched slightly forward, balanced by his left elbow bent on the table. Klimt, his back to the viewer, sits at the opposite end of the table, elbows bent, both hands held up in fists. The Last Supper motif is obvious.

The painting, which Schiele began planning in January 1917, was the source for the poster for the 49th Secessionist Exhibition held in March 1918. There are critical differences between the poster and painting, most notably the acknowledgment of Klimt’s death. In the poster the chair once inhabited by Klimt is empty, making Schiele the de facto head of the table. Books have replaced the round plates of food that originally covered the table, eliminating any visual reference to The Last Supper, perhaps a sign of Vienna’s increasingly limited food supply. Schiele’s elbows are still bent on the table, but the gesture is reduced, humble; they now support a book instead of the weight of the artist. The tonal changes between painting and lithograph are striking.

The 49th Secessionist Exhibition proved to be a triumph for Schiele. He showed forty-five pictures at the exhibition and sold most of them. The exhibition established Schiele as Klimt’s successor both in Vienna and internationally. It was a grand achievement for an artist just on the edge of his twenty-eighth birthday. The Family (The Squatting Couple) (1918) was one of the paintings Schiele sold at the exhibition. He once again conjured himself as a being of elongated limbs and swollen joints, wild hair and arched eyebrows. A half-nude woman echoes his squat in the foreground, an infant on the ground between her knees. The Family, which is considered unfinished even though Schiele sold the work, is often wistfully cited as Schiele’s unrealized dream, a manifestation of a family that would never appear. It’s a romantic reading of an artist who seems to inspire such interpretations, but it isn’t accurate. The painting is not of Edith, who would not have been pregnant when he produced the work, and, according to his sister-in-law, the infant was originally a bouquet. It may have been a study for a larger project, a mausoleum that was to have been decorated with frescos representing Death, the Stages of Life, and Earthly Existence, among other subjects. The painter Johannes Fischer, who frequented Schiele’s studio in 1918, said that all of Schiele’s later paintings were studies for the mausoleum, works left akimbo by his own precocious trip to the grave.

Success at the exhibition had real, if short-lived, material results for Schiele, including the novel experience of financial solvency. He bought a new, larger studio on the Wattmanngasse and a larger apartment for himself and Edith. But Schiele’s success proved to be a kind of double-edged sword. Shortly after the exhibition and the move, Edith fell pregnant. The post-1914 world was unstable, and Schiele struggled to heat his studio; coal was nearly impossible to obtain, and food remained scarce. It was a confluence of crises: hunger, cold, war, and a pandemic whose second wave was forming.

Schiele had married Edith Harms in 1915, five days before his twenty-fifth birthday and four days before he was conscripted into active military service. The first two years of their marriage were defined by the war. Edith followed Schiele to his first posting in Prague and then to a prisoner-of-war camp in Mühling where he served as the camp’s secretary. His notebooks from that period are filled with poignant drawings of Russian POWs. (Schiele was a prolific draftsman.) Schiele had misgivings about the brutality of the war. “We live in the most violent time the world has ever seen,” he wrote in a letter to his younger sister Gerti shortly after Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia in July 1914. “Hundred of thousands of people perish miserably, everyone must bear his fate of either living or dying; we have become hard and fearless. That which was before 1914 belongs to another world.” It was a prescient thought for considering the future of both Schiele and Europe at large. His 1915 painting Death and the Maiden is often interpreted as Schiele’s final word on his four-year relationship with model and romantic partner Wally Neuzil. (“I intend to get married, advantageously. Not to Wally,” Schiele wrote in a letter to a friend four months before he wed Edith, the daughter of a comfortable middle-class family. Neuzil would die before him, in 1917, of scarlet fever she caught working as a nurse in what is now Croatia.)

A drawing from 1915 introduces Edith, elbows planted on her hips. She wears the black-and-white striped dress that appeared over and over again in portraits of her from this period, her long fingers disappearing into the folds of fabric. In another drawing also from 1915, elbows bent, hands clasped, the dress is rendered in color, the black-and-white stripes contrasted with the red detailing on the pronounced collar. Edith had made the dress from the fabric of Schiele’s curtains. In photographs it’s an assault on the eyes, but Schiele’s rendition of the garment is a softer, kinder, far more flattering portrayal. (The curtains with those same bold black and-white stripes appear in a small canvas Schiele produced of his desk.) In a large-scale portrait of Edith from that year, Portrait of the Artist’s Wife, Standing (Edith Schiele in Striped Dress), the dress has been transformed into stripes of greens and yellows, blues and purples. The painting seems festive, considering Schiele likely spent his days digging trenches. His sketchbooks and drawings are filled with images of Edith, who followed him from assignment to assignment until January 1917, when, after months of lobbying, Schiele was finally assigned to a supply depot in Vienna. Schiele spent the next year working furiously, planning for the Secessionist exhibition even as war and political instability threatened him and illness loomed. It feels impossible to look at the work from that year without being bogged down by the knowledge of what’s to come.

Edith was likely infected around October 19, the week that proved to be Vienna’s deadliest. “The illness is extremely serious and life-threatening. I am already preparing myself for the worst,” Schiele wrote to his mother on October 27. Schiele was right to be worried about his wife: Edith was six months pregnant, and the Spanish flu had a predilection for pregnant women. The same day Schiele’s letter reached his mother, Edith, unable to breathe enough to speak, picked up a pen and wrote with a shaky hand, “I love you eternally and love you more and more infinitely and immeasurably.” The next morning, on October 28, she was dead.

Schiele, already ill himself, drew his last portrait of Edith. Hair piled on top of her head, eyes open, thin fingers curled beneath her cheekbone. The elbow just outside of the composition’s frame, implied by the position of her skeletal fingers, one of which still wears a ring. “Edith Schiele is no more,” he wrote in a short note to Gerti the next morning. These two scraps of paper constitute the last drawing Schiele ever produced, the last letter he ever wrote.

After Edith’s death, Schiele was moved to his in-laws’ home, already too weak to leave his bed. His last visitors reportedly communicated with Schiele by way of mirror, afraid that they too might be infected. Journalist Laura Spinney writes in Pale Rider: The Spanish Flu of 1918 and How It Changed the World that the virus was particularly fond of “those in the prime of life—people in their twenties and thirties, especially men.” Schiele died three days after his wife. Schiele’s elbows—bent with one hand behind his head, bent so that the other hand supports his chin—were documented for the last time. Five days later, the Austro-Hungarian Empire came to an official end.

In the middle of Vienna’s city center sits the Pestsäule, a plague column erected in remembrance of the Great Plague of 1679. Commissioned by Leopold I, the theatrically baroque column is less a memorial to the dead and more of a monument to Habsburg power, which, if the chubby gilt cherubs of the Pestsäule are to be believed, delivered the city from the bubonic plague. The details of the iconography aren’t particularly important—what is important is that the plague outbreak was given a large, imposing monument. No such grand monument exists for the victims of the Spanish flu. Their monument is much humbler. It is a deathbed photograph, an empty chair in an exhibition poster, a note from a wife to her husband written with a shaky hand. It is a simple line drawing and a black-and-white dress. It is everything that has disappeared but demands to be seen in Schiele’s work. It is the impossibility of transcendence. It is in bent elbows, working, seen and implied.