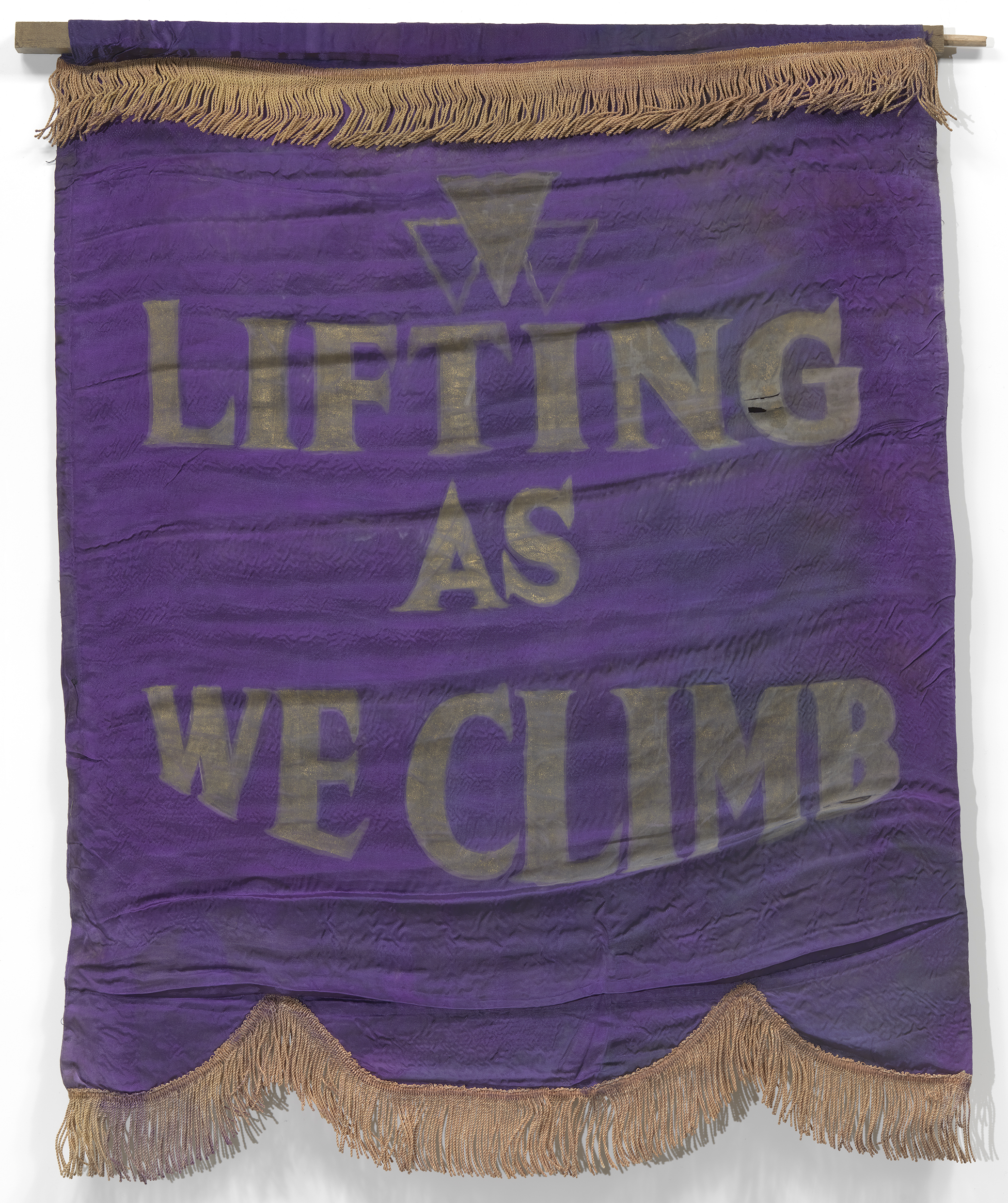

Banner with motto of the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs, c. 1924. Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture.

During the 2020 U.S. presidential election season, we will feature voices from the past who told stories that rhyme with the one unfolding before us—stories of those who got out the vote, narrated trips to the polls, tested the limits of their political power, cheated their way to an electoral victory, or were prevented from exercising any of theses democratic roles by the actions of their leaders or neighbors.

Frances Ellen Watkins Harper spent her career as a prolific writer and social reformer trying to get her fellow Black readers and those alongside her in the abolitionist, temperance, and suffrage movements to understand power: who has it, the avenues by which those who don’t have it might acquire it, and that using power to help others is necessary if one claims to be a good Christian.

The didactic novel Sowing and Reaping—published serially starting in 1876 in the Christian Recorder, the official newspaper of the African Methodist Episcopal Church—is dense with characters and plots. Harper’s admirable characters value justice, solidarity, and the temperance movement; those forced to do the most reaping in the book are selfish sinners. In the scene below, Mrs. Gladstone—the foremost mouthpiece of the temperance movement in the book—discusses Jeanette Roland, one of the aforementioned sinners, with her daughters Annette and Mary and her friend Tabitha Jones. Eventually, the conversation broadens beyond one woman and one issue to include the prospects of all women, especially those who prefer to leave their fates in the hands of others and their untapped power unclaimed. The scene ends with the realization that putting power into the hands of women means that the selfish among them will also benefit.

Ten years earlier, in 1866, Harper had given a speech at the National Women’s Rights Convention in New York City, making a point about the limits of expanding suffrage.

I do not believe that giving the woman the ballot is immediately going to cure all the ills of life. I do not believe that white women are dewdrops just exhaled from the skies. I think that like men they may be divided into three classes, the good, the bad, and the indifferent. The good would vote according to their convictions and principles; the bad, as dictated by prejudice or malice; and the indifferent will vote on the strongest side of the question, with the winning party.

“Do you think Jeanette is happy? She seems so different from what she used to be,” said Miss Tabitha Jones to several friends who were spending the evening with her.

“Happy!” replied Mary Gladstone. “I don’t see what’s to hinder her from being happy. She has everything that heart can wish. I was down to her house yesterday, and she has just moved in her new home. It has all the modern improvements, and everything is in excellent taste. Her furniture is of the latest style, and I think it is really superb.”

“Yes,” said her sister, “and she dresses magnificently. Last week she showed me a most beautiful set of jewelry, and a camel’s-hair shawl, and I believe it is real camel’s hair. I think you could almost run it through a ring. If I had all she has, I think I should be as happy as the days are long. I don’t believe I would ‘let a wave of trouble roll across my peaceful breast.’ ”

“Oh! Annette,” said Mrs. Gladstone, “don’t speak so extravagantly, and I don’t like to hear you quote those lines for such an occasion.”

“Why not, Mother? Where’s the harm?”

“That hymn has been associated in my mind with my earliest religious impressions and experience, and I don’t like to see you lift it out of its sacred associations for such a trifling occasion.”

“Oh Mother, you are so strict. I shall never be able to keep time with you, but I do think, if I was as well-off as Jeanette, that I would be as blithe and happy as a lark, and instead of that she seems to be constantly drooping and fading.”

“Annette,” said Mrs. Gladstone, “I knew a woman who possesses more than Jeanette does, and yet she died of starvation.”

“Died of starvation! Why, when, and where did that happen? And what became of her husband?”

“He is in society, caressed by the young girls of his set, and I have seen a number of managing mamas to whom I have imagined he would not be an objectionable son-in-law.”

“Do I know him, Mother?”

“No! And I hope you never will.”

“Well, Mother, I would like to know how he starved his wife to death and yet escaped the law.”

“The law helped him.”

“Oh Mother!” said both girls, opening their eyes in genuine astonishment.

“I thought,” said Mary Gladstone, “it was the province of the law to protect women. I was just telling Miss Basanquet yesterday, when she was talking about woman’s suffrage, that I had as many rights as I wanted and that I was willing to let my father and brothers do all the voting for me.”

“Forgetting, my dear, that there are millions of women who haven’t such fathers and brothers as you have. No, my dear, when you examine the matter a little more closely, you will find there are some painful inequalities in the law for women.”

“But Mother, I do think it would be a dreadful thing for women to vote. Oh! Just think of women being hustled and crowded at the polls by rude men, their breath reeking with whiskey and tobacco, the very air heavy with their oaths. And then they have the polls at public houses. Oh, Mother, I never want to see the day when women vote.”

“Well, I do. Because we have one of the kindest and best fathers and husbands and good brothers, who would not permit the winds of heaven to visit us too roughly, there is no reason we should throw ourselves between the sunshine and our less fortunate sisters who shiver in the blast.”

“But Mother, I don’t see how voting would help us. I am sure we have influence—I have often heard Papa say that you were the first to awaken him to a sense of the enormity of slavery. Now Mother, if we women would use our influence with our fathers, brothers, husbands, and sons, could we not have everything we want?”

“No, my dear, we could not, with all our influence we never could have the same sense of responsibility which flows from the possession of power. I want women to possess power as well as influence. I want every Christian woman as she passes by a grogshop or liquor saloon to feel that she has on her heart a burden of responsibility for its existence. I hold, my dear, that a nation as well as an individual should have a conscience, and on this liquor question there is room for woman’s conscience not merely as a persuasive influence but as an enlightened and aggressive power.”

“Well Ma, I think you would make a first-class stump speaker. I expect when women vote we shall be constantly having calls for the gifted and talented Mrs. Gladstone to speak on the duties and perils of the hour.”

“And I would do it. I would go among my sister women and try to persuade them to use their vote as a moral lever not to make home less happy but society more holy. I would have good and sensible women, grave in manner and cultured in intellect, attend the primary meetings and bring their moral influence and political power to frown down corruption, chicanery, and low cunning.”

“But Mother, just think: if women went to the polls, how many vicious ones would go?”

“I hope and believe for the honor of our sex that the vicious women of the community are never in the majority, that for one woman whose feet turn aside from the paths of rectitude that there are thousands of feet that never stray into forbidden paths, and today I believe there is virtue enough in society to confront its vice and intelligence enough to grapple with its ignorance.”

“Why Mrs. Gladstone,” said Miss Tabitha, “you are as zealous as a new convert to the cause of woman suffrage. We single women who are constantly taxed without being represented know what it is to see ignorance and corruption striking hands together and voting away our money for whatever purposes they choose. I pay as large a tax as many of the men in the city of A.P., and yet cannot say who shall assess my property for a single year.”

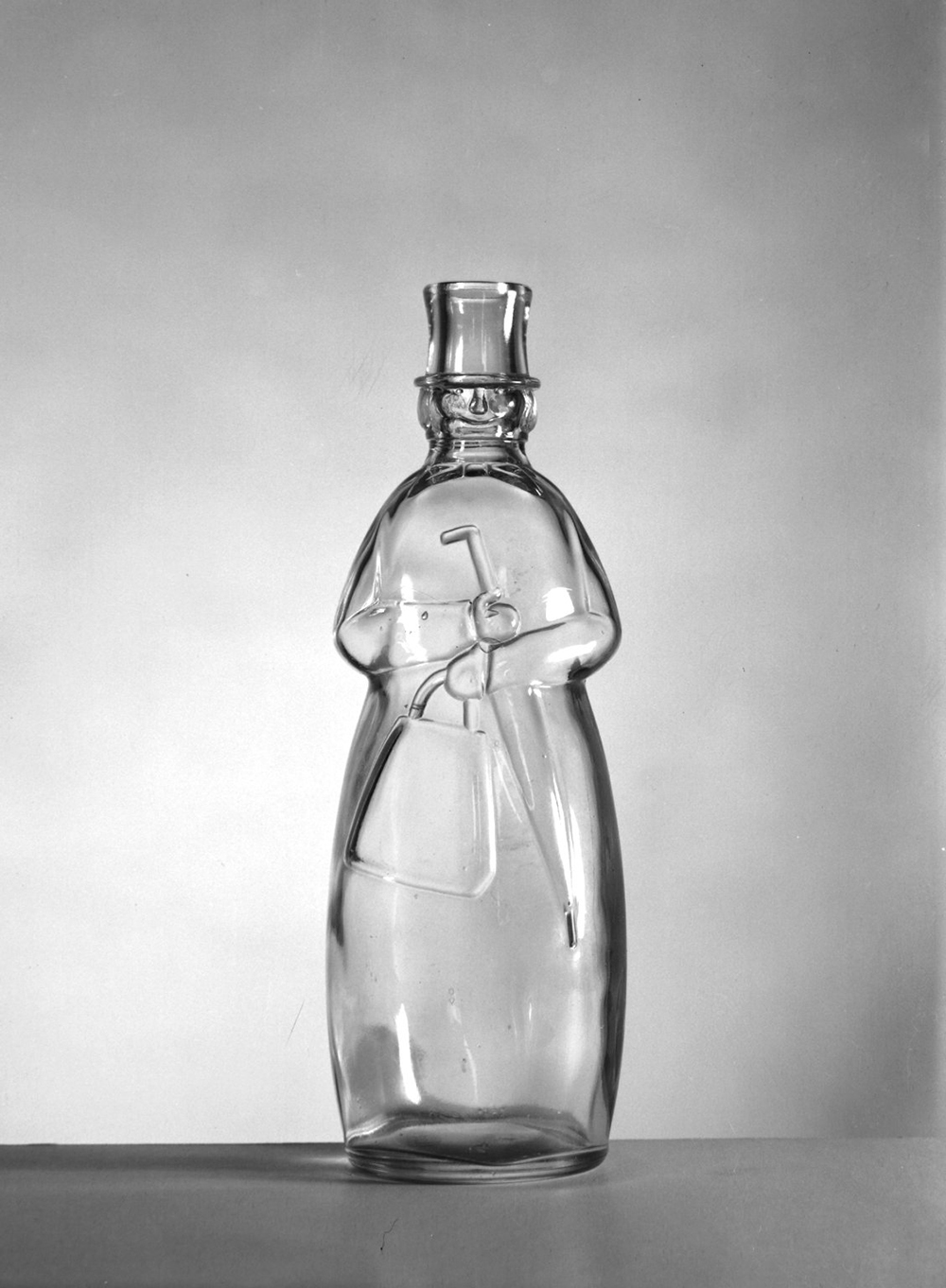

“And there is another thing,” said Mrs. Gladstone, “that ought to be brought to the consideration of the men, and it is this. They refuse to let us vote and yet fail to protect our homes from the ravages of rum. My young friend, whom I said died of starvation, foolishly married a dissipated man who happened to be rich and handsome. She was gentle, loving, sensitive to a fault. He was querulous, fault-finding, and irritable, because his nervous system was constantly unstrung by liquor. She lacked tenderness, sympathy, and heart support, and at last faded and died not of starvation of the body but of atrophy of the soul, and when I say the law helped, I mean it licensed the places that kept the temptation ever in his way. And I fear that is the secret of Jeanette’s faded looks and unhappy bearing.”

No, Jeanette was not happy. Night after night would she pace the floor of her splendidly furnished chamber waiting and watching for her husband’s footsteps. She and his friends had hoped that her influence would be strong enough to win him away from his boon companions, that his home and beautiful bride would present superior attractions to Anderson’s saloon, his gambling pool, and champaign suppers, and for a while they did. But soon the novelty wore off, and Jeanette found out to her great grief that her power to bind him to the simple attractions of home were as futile as a role of cobwebs to moor a ship to the shore when it has drifted out and is dashing among the breakers. He had learned to live an element of excitement, and to depend upon artificial stimulation, until it seemed as if the very blood in his veins grew sluggish fictitious excitement was removed.

Read the other entries in the series: Andrew Dickson White, John Milton, Sydney Smith, George O. Dunnell, and Rutherford B. Hayes.