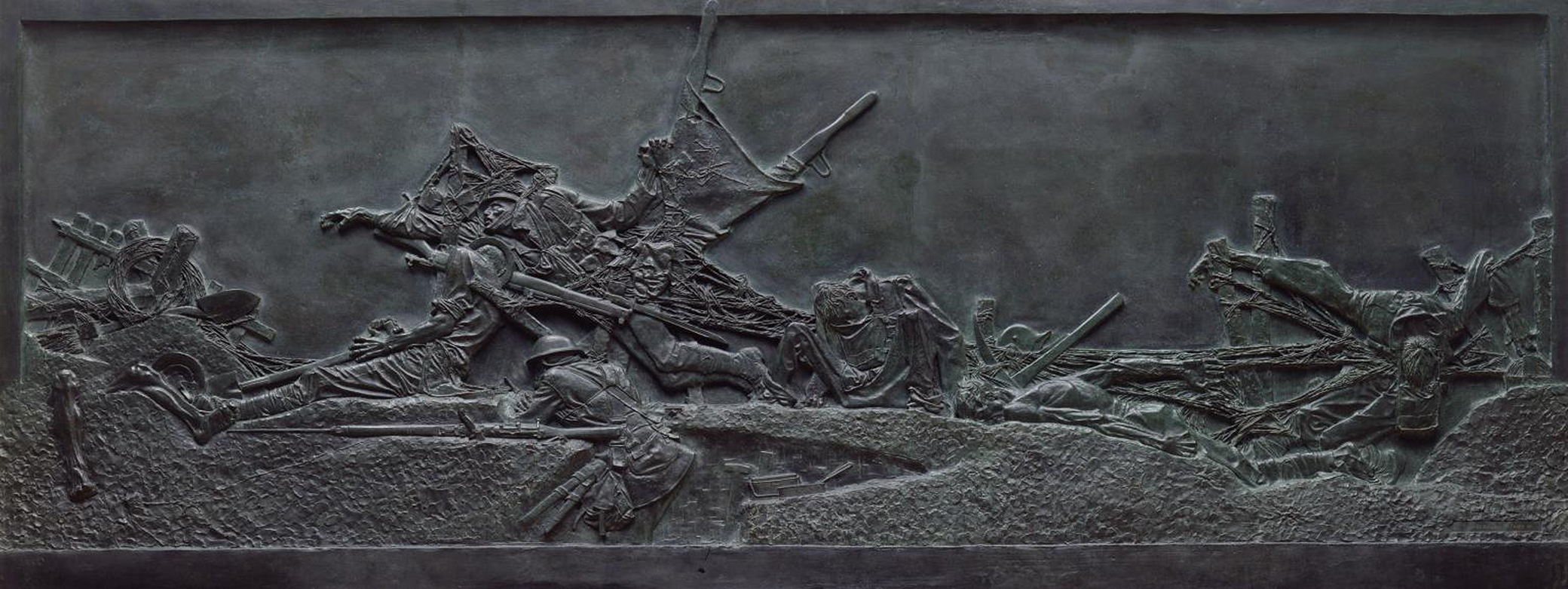

No Man’s Land, by Charles Sargeant Jagger, c. 1919. Photograph © Tate (CC-BY-NC-ND 3.0).

The hands of the clocks reached 10:59 am, the last minute of the war on the Western Front. In that last minute before 11:00, clock-watching men listened to the tick-tick-tick of the watch and the tick-tock of the clock. At Oudenaarde, Philip Clayton had bought mouth organs and handed them out to troops, so that they had something to play when peace arrived. On the River Dender in Belgium, British troops had reportedly attacked a village called Lessines at 10:55, securing a bridgehead at 10:58 and taking the village at 10:59, eventually capturing four officers and 102 other ranks. The pessimist might be able to understand such foolhardiness: the war could resume again soon, maybe within hours, so it was sensible to take as much land and as many prisoners as possible while the enemy were at their weakest. But an attack by Canadian troops near Mons at 10:58 resulted in the death of Private George Lawrence Price. A Liverpool Pals battalion was at the France–Belgium border near Clairfayts when “at 10:59 am, Captain R. West, the Staff Captain of the 199th Brigade, rode up with a message to the effect that all hostilities would cease at 11:00.” Artillery fired their last shells, often with tremendous intensity, right up to the cease-fire. If nothing else, they were disposing of shells so that they didn’t have to transport them back to base or back to Britain. Germans died in fighting near Ath on the verge of the cease-fire. American soldier Henry Gunther died at 10:59 and is considered to be the last soldier to be killed in the war, when he was shot by a machine gun at Chaumont-devant-Damvillers. Another member of the American forces was apparently seriously injured by a shell also fired at 10:59, and he described from a hospital bed later that day how he came to be injured:

He said he was on duty in the telephone exchange of one of the Artillery regiments, and the message came over the wire, “It is 11 o’clock and the war is—” At this point, he said, a shell landed and burst in the room, killing his “buddy” and seriously wounding him. So far as I have been able to learn, these were the last casualties of the war. The shell was doubtless fired a second or so before 11 o’clock, and reached its mark a few seconds after the clock had struck the hour which brought peace to more millions of people than had any other hour in the world’s history.

Dying just before the end of the war became an example of extreme bad luck, an instance of how the gods—or the generals—play with us for their sport. In Muriel Spark’s The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie (1961), one of the few things we know about Miss Brodie’s lost lover (if he existed at all) is that he died a week before the Armistice; in the film Goodbye, Mr. Chips (1939) a key character dies in battle on November 6, which is considered all the more tragic because peace has almost arrived; and in Dorothy L. Sayers’ The Unpleasantness at the Bellona Club (1928), we’re told that a man died half an hour before the end of the war—“damnable shame.” Those who died that morning were to be almost novelties, standing out on war memorials and in newspapers because of the date of their death. A slightly earlier Armistice could have saved many lives; and no one knows what those who fell might have given to the world had they lived. At 11:00 the game was over. There was silence. It was like going deaf. This was what the poet John McCrae had foreseen in “The Anxious Dead” as “earth enwrapt in silence deep.” The story of the war came to an end and this was the blank white page after the book’s last words. The front even looked like a white page. The Times the following day contained a report on the sudden silence at Sedan, where until 1:30 pm there was “a thick white mist over the whole district, which hid everything over a distance of twenty yards from you”:

In one way this dense white shroud, though not in keeping with the joyfulness of the occasion, agreed with what was by far the most striking feature about the cessation of hostilities—uncanny silence. After what I have known of the front for the last four years or more, it seems incredible to be standing here with all the paraphernalia of war lying about, and the air to be absolutely still, and the silence unbroken by a single shot.

And that was what the men themselves seemed to feel. When the appointed hour arrived they made no demonstration. They just stopped firing, and there was no cheering and no excitement. The four years’ struggle was over. The four years’ noise was at an end. That was all. There was nothing to do except to be glad, and they were glad.

The white mist or fog, a “shroud” here, was described by Mildred Aldrich as a huge white flag of truce wrapped around the world. The war had become a ghost, a blankness. The fog was like soundproofing, helping to create the silence. The strangeness of the Armistice agreement in the forest had been continued by the white mist and the arrival of the uncanny silence of the cease-fire. “Uncanny” was a word often used to describe the silence. Elsewhere it would be unremarkable, but at the Western Front silence seemed unnatural. “Unheimlich,” you might say in German—Sigmund Freud’s seminal essay on the unheimlich, translated as “The Uncanny,” was published in 1919, and he notes that the uncanny is not only unfamiliar but also frightening. “It was the appalling new silence of things that soothed and unsettled them in turn…the stillness stung in their ears as soda-water stings on the palate,” as Kipling said of the Irish Guards, and he quoted one soldier who said that “it felt like falling through into nothing…Listening for what wasn’t there.”

“Worried by silence, sentries whisper, curious, nervous,” Wilfred Owen had written in “Exposure”—soldiers had learnt to be wary of silence. Freud, too, associated silence with death. In the poetry of the war years, such as in Ivor Gurney’s “The Silent One,” to be silent was to be dead.

It was a day for the weird, the eerie, the strange. There was also the coincidence that British soldiers were stopping at the spot where their war began, even sharing a parish with skeletons from 1914. At the end of the fighting, the line ran to the east of Mons, across the old Mons battlefield of 1914, so the end of the war was a mirror image of the start. It was one of those strange coincidences that Shakespeare is allowed to get away with. The painting We Saw You Going, But We Knew You Would Come Back (1919), by the elderly illustrator Richard Caton Woodville, depicts a cavalryman passionately kissing a local woman when the 5th Lancers entered Mons on November 11, having first arrived there at the start of the war as part of the British Expeditionary Force. The painting emphasizes not only the kiss, as a key occurrence and symbol of the Armistice, but also the circularity of it all (the painting itself is a circular canvas). One soldier pointed out that he had ended up exactly where he started:

It was a strange coincidence that, after more than four years of war, we should finish fighting within less than a mile of the place where we had first come into action against the Germans, while with us was the same Horse Battery that came into action with us at the same place in August 1914. This battery must have fired about the first shell of the war, and now, on the same ground, it was going to fire the last.

It was, as a German soldier noted, “as though the beginning and the end were shaking hands.” One of the very unlucky ones, believed to be the last British soldier killed in action, was George Edwin Ellison of the Royal Irish Lancers, a middle-aged man who served right from the beginning of the war in August 1914. He died on November 11, 1918, at Mons, where he started fighting in that August of 1914. He is buried close to the first British soldier killed in action in the war, in St. Symphorien near Mons, the military cemetery where the Canadian George Lawrence Price is also buried.

Similarly, Sedan, shrouded in mist, now a site of Germany’s defeat, had been the site of France’s defeat by Prussia and the surrender of Napoleon III in 1870. The Daily Telegraph commented:

We must not look idly at coincidences like these, as though some malicious Fate were decreeing a series of theatrical incidents for our behoof. Our proper attitude surely is one of silence and awe, as we see God’s judgements executed, the Divine laws vindicated—to prove that there is a justice which never sleeps, and a moral government of the world which, though often baulked and delayed, never fails to assert its everlasting authority.

Thomas Hardy was a poet with an eye—and an ear—for the coincidental, for the strange, for the uncanny and for malicious fate, and he described the 11 am silence in “ ‘And There Was a Great Calm’ (On the Signing of the Armistice, Nov. 11, 1918).” The Armistice arrives in the fifth stanza. It isn’t one of Hardy’s best poems, and the alliteration is possibly too heavy, but it captures the moment, and its strange diction, its biblical echoes, and its “Spirits” give the poem a suitable strangeness:

V

So, when old hopes that earth was bettering slowly

Were dead and damned, there sounded “War is done!”

One morrow. Said the bereft, and meek, and lowly,

“Will men some day be given to grace? yea, wholly,

And in good sooth, as our dreams used to run?”

VI

Breathless they paused. Out there men raised their glance

To where had stood those poplars lank and lopped,

As they had raised it through the four years’ dance

Of Death in the now familiar flats of France;

And murmured, “Strange, this! How? All firing stopped?”

VII

Aye; all was hushed. The about-to-fire fired not,

The aimed-at moved away in trance-lipped song.

One checkless regiment slung a clinching shot

And turned. The Spirit of Irony smirked out, “What?

Spoil peradventures woven of Rage and Wrong?”

VIII

Thenceforth no flying fires inflamed the gray,

No hurtlings shook the dewdrop from the thorn,

No moan perplexed the mute bird on the spray;

Worn horses mused: “We are not whipped to-day”;

No weft-winged engines blurred the moon’s thin horn.

“Strange, this!” Hardy’s horses might not know why they aren’t whipped but there’s a memorable description of November 11, 1918, in Jane Duncan’s book My Friends the Miss Boyds (1959), set on the Black Isle in the north of Scotland and based on her own childhood, where the horses start behaving very oddly, running, dancing, and emanating “strange excitement” as if they know that the Armistice has arrived, even though the people don’t. Then a destroyer brings the news that the war is over. Similarly, Katherine Mansfield noted that, at the wonderful moment of peace’s arrival, nature seemed to know, because “I saw that in our garden a lilac bush had believed in the South wind and was covered in buds.”

The war was over, “War is done!,” calm fell on the battlefield. Descriptions such as Hardy’s give a sense of 11 am as motion suddenly frozen, a clock stopped—“the about-to-fire fired not”—and the arrival of peace was defined by absence, by what it was not. Peace was no war, no guns, no fighting, no death: “no flying fires,” “no hurtlings,” “no moan,” “no weft-winged engines.”

Excerpted from Peace at Last: A Portrait of Armistice Day, 11 November 1918 by Guy Cuthbertson, published by Yale University Press in November 2018. Reproduced by permission.