March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, with Martin Luther King Jr. in the center and Joachim Prinz on the far left, 1963. American Jewish Historical Society.

We are the dogs, and we are going to Washington to rid ourselves of the fleas.

—Carl Browne, 1894

There were few reasons to demonstrate along the shores of the Potomac before Pierre Charles L’Enfant laid out the streets of the federal city in 1791. But within sixty years of the District’s inception—when a group of unemployed workers tried to disrupt Franklin Pierce’s inaugural parade—Americans were taking their grievances to the nation’s capital. Here are a dozen of the National Mall’s most memorable demonstrations.

Million Man March (1995)

Somewhere between 400,000 and 900,000 people—led by Nation of Islam minister Louis Farrakhan—gather on the Mall to call for improved civil rights. It is the first public march to provide an independent financial audit of its operations. “The march was intended to establish and promote economic self-reliance,” says the report, “and be morally uplifting.”

March for Women’s Lives (1992)

Seven hundred and fifty thousand people march for reproductive rights, protesting the Supreme Court’s anticipated decision on the Pennsylvania abortion case Planned Parenthood v. Casey. The rally has its effect: a pro-choice president is elected, and the Court leaves Roe v. Wade intact.

March for Equality (1978)

More than 100,000 people march for the passage of the Equal Rights Amendment, calling on Congress to extend the time limit for ratification. The period is extended, but the opposition gains ground; the amendment musters only thirty-five of the required thirty-eight state ratifications.

Nixon’s Second Inauguration (1973)

A hundred thousand people gather to demand an end to the Vietnam War, a larger but relatively tamer crowd than that gathered for Nixon’s first inauguration. Thirty-three arrests are reported. (Approximately eighty Democratic lawmakers boycott Nixon’s second inauguration.) In little more than a year and a half, Nixon resigns from the presidency.

Black Panther Rally (1970)

This demonstration, held on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial to promote a revolutionary people’s constitutional convention, draws a thousand people. It probably marks the apogee of the Black Panther movement. “Things in America are fucked up,” reads the call to the convention. “The system doesn’t work, it doesn’t serve human needs; it serves capitalist greed which is ravaging the earth’s air, land, and water in addition to killing people.”

Moratorium to End the War in Vietnam (1969)

A group of 600,000 people gather to protest the war, in which 45,000 Americans had already been killed. “We seem to be approaching an age of the gross,” Vice President Spiro Agnew says in a speech about the demonstration. “Persuasion through speeches and books is too often discarded for disruptive demonstrations aimed at bludgeoning the unconvinced into action.” The Vietnam War does not end for another six years.

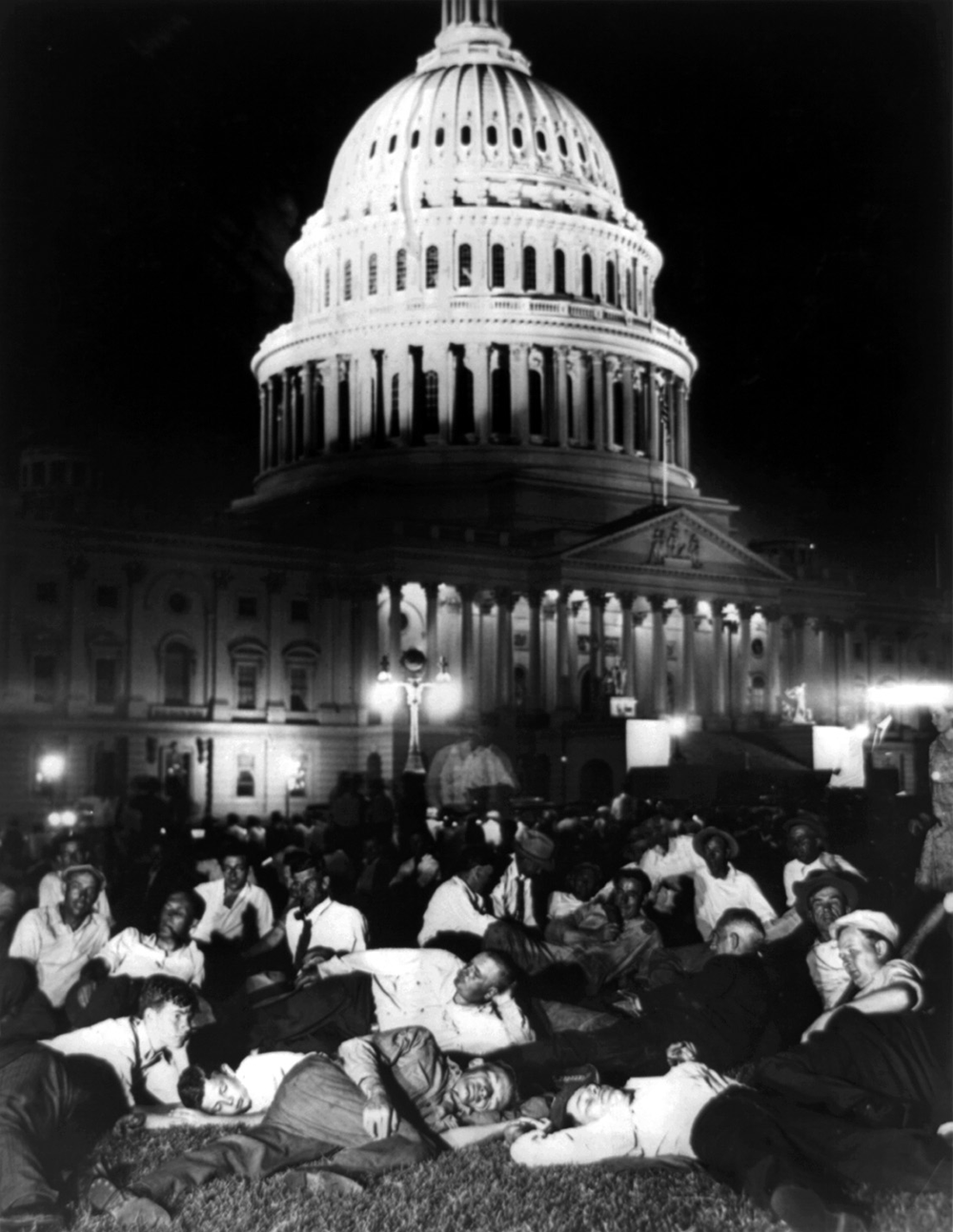

March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom (1963)

Two hundred and fifty thousand people join the march, which is one of the largest civil rights demonstrations in U.S. history. The AFL–CIO declines to support the march. Martin Luther King Jr. delivers his “I Have a Dream” speech on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial. The protest is said to have led to 1964’s Civil Rights Act and 1965’s Voting Rights Act.

Bonus Expeditionary Forces (1932)

Seventeen thousand World War I veterans go to Washington to demand immediate payment of promised bonuses for their war service; some families build shanties on the Anacostia Flats. President Herbert Hoover orders police to remove marchers. In the ensuing skirmish between vets and police, two vets are killed. The U.S. Army takes over; General Perry Miles drives out the demonstrators with tanks and teargas.

Ku Klux Klan March (1925)

Thirty thousand Klansmen march in full regalia down Pennsylvania Avenue on a hot summer day. District commissioners had granted permission for the parade on the condition that Klansmen march without masks. “The parade was grander and gaudier, by far, than anything the wizards had prophesied,” wrote H.L. Mencken for the New York Sun. “It was longer, it was thicker, it was higher in tone. I stood in front of the Treasury for two hours watching the legions pass.” More than a hundred men and women are hospitalized for heat stroke and dehydration.

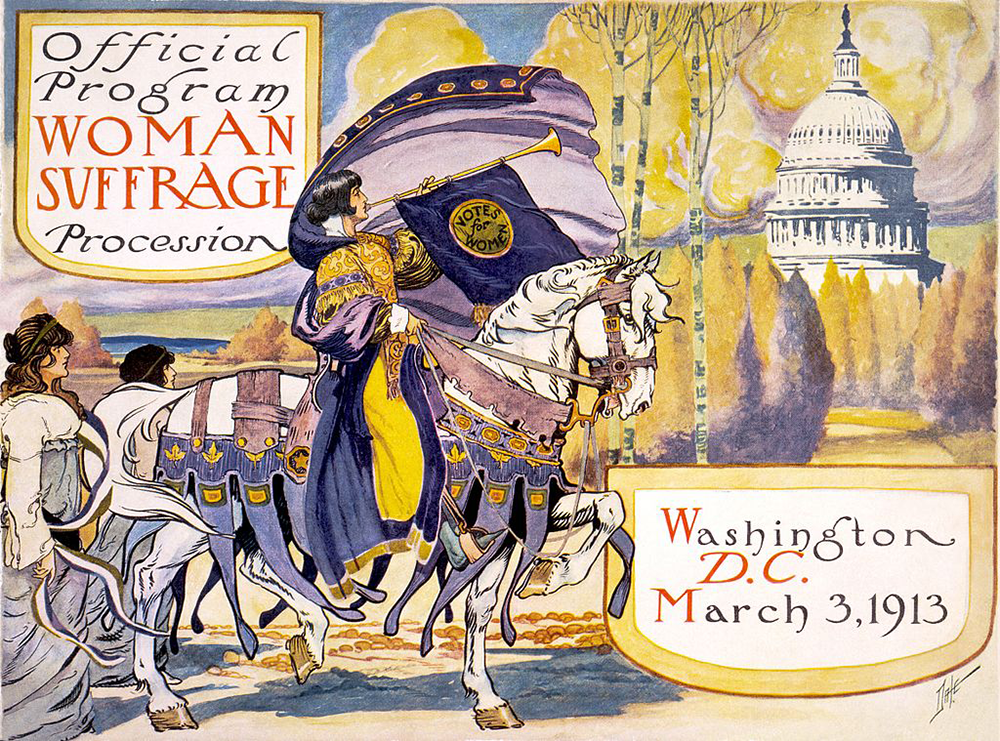

The Woman Suffrage Procession (1913)

In Washington on the day of Woodrow Wilson’s inauguration, eight thousand women march for the right to vote. The parade includes nine bands, four mounted brigades, twenty floats, and a performance near the Treasury Building. The suffragists are attacked by male onlookers; police refuse to stop their mistreatment. U.S. Army troops on horseback are brought in to control the crowd. A hundred marchers are injured. The chief of police is forced to step down in 1915. In 1920 the Nineteenth Amendment secures the vote for women.

Coxey’s Army (1894)

In the first large-scale protest on the National Mall, two thousand unemployed workers—an “Army of the Unemployed” led by populist Jacob Coxey—are confronted by fifteen hundred soldiers stationed in Washington. A law prohibits gatherings on the Capitol grounds; when Coxey tries to speak at the Capitol, he is arrested (for walking on the grass) and jailed for twenty days. “We have come to the only source,” Coxey says later of the march, “which is competent to aid the people in their day of dire distress.”

The American War (1814)

Forty-five hundred troops sack the city and set fire to the Capitol, Treasury, and White House, drinking President James Madison’s wine. The next day, British troops led by Admiral George Cockburn and Major General Robert Ross burn the Navy Yard and the State, War, and Navy building and desecrate a monument dedicated to veterans of the First Barbary War. “They burned the Capitol, the White House, and the Department buildings,” writes Henry Adams, “because they thought it proper, as they would have burned a negro kraal or a den of pirates. Apparently they assumed as a matter of course that the American government stood beyond the pale of civilization; and in truth a government which showed so little capacity to defend its capital, could hardly wonder at whatever treatment it received.”

All numbers of crowd size are estimates; none should be considered definitive.