Lead curse, scratched onto sheet metal that reads, “I curse Tretia Maria and her life and mind and memory and liver and lungs mixed up together, and her words, thoughts and memory; thus may she be unable to speak what things are concealed, nor be able...nor....” © The Trustees of the British Museum.

In early January 532, a fistfight broke out between two rival factions of Byzantine chariot-racing fans. This run-of-the-mill sports rivalry would set in motion a series of events that, in a matter of weeks, would threaten the sovereignty of the emperor Justinian and leave tens of thousands dead.

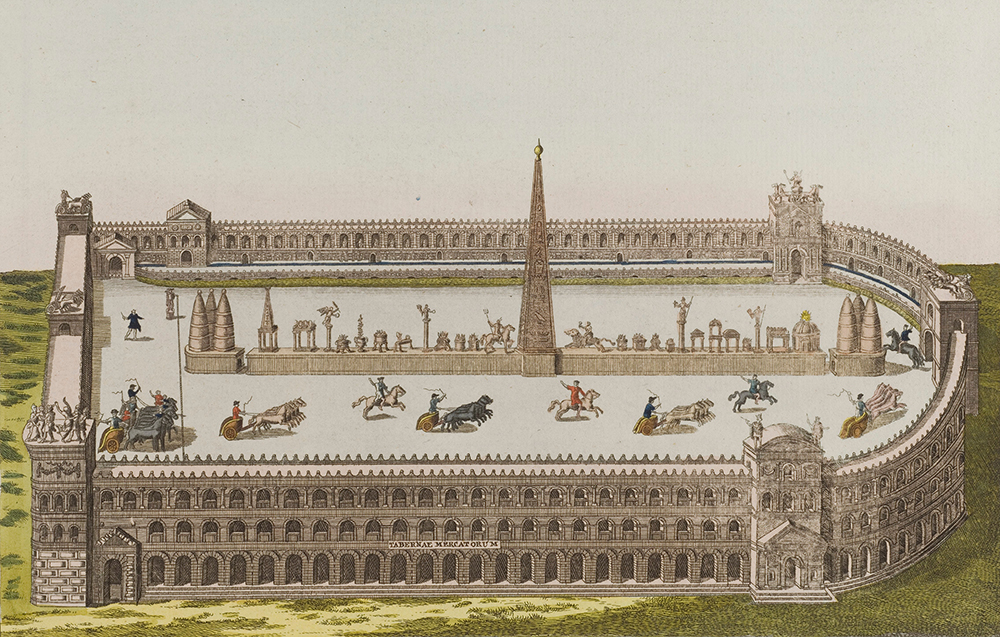

Several brawlers on both sides—referred to as the Blues and the Greens after the colors of their favored charioteers’ racing tunics—were arrested and sentenced to death by hanging. At the execution, the scaffold broke and two convicts survived: a fan from each side, one Blue and one Green. When the emperor arrived at the chariot races a few days later, on January 13, he ignored pleas for clemency toward the survivors from both factions. The Blues and the Greens responded by rioting, setting fires, and occupying the Hippodrome, Constantinople’s racetrack.

After five days of chaos, Justinian returned to the Hippodrome to publicly apologize for refusing to pardon the two survivors. It was rejected, and the riot was put to an end only when Justinian (convinced by his wife, Theodora, not to renounce his title and flee to safety) ordered his two best generals and their troops to storm the stadium. Though numbering no more than four thousand, these troops slaughtered at least thirty thousand rioters, according to chroniclers. “The chariot races,” one Byzantine historian tells us, “were not held for a long time” afterward.

There are many bizarre aspects to this riot—not least its staggering body count—but the strangest might be the collaboration of Blues and Greens fans. Unlike modern horse racing, where fans root for a particular horse or jockey, Roman charioteers were organized into two levels of four teams, all of which are attested as early as the first century bc. On top were the more prestigious Blues and Greens, and below them, serving as something like farm teams, were the Reds and Whites. These teams transcended geographic boundaries; every city with a major racetrack had all four. There was no such thing as a “hometown team.”

Still, rivalries were fierce. Fans did not intermingle in the stands but watched races segregated by allegiance, as factional inscriptions carved into the stone seats encircling racetracks across the Roman Empire reveal. A contentious race was a common trigger for violence, but sometimes no such pretext was necessary. In 501, for example, Greens fans illegally snuck weapons into the Hippodrome to attack Blues fans during a race; three thousand spectators allegedly died in the ensuing panic. Nineteen years later, out-of-control Blue-Green violence forced the permanent cancellation of the renewed Olympic Games, which had been celebrated in Antioch for three hundred years.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, historians could conceptualize the rabid animosity between Roman chariot-racing fans only by constructing elaborate theories of sociopolitical meaning. Because the Blues seem to have been especially popular among Constantinople’s ruling class in the decades leading up to the riot—Justinian’s empress Theodora spent her early years as a Blues-allied circus performer—they were cast as the establishment team. The Greens, whose supporters had been banned from holding government offices for three years in the 490s as punishment for unruly behavior, were accordingly interpreted as the team of the people. Although these social factors may have influenced an individual’s decision to root for one team or the other on some subconscious level, both major teams had supporters from all levels of society, including the imperial family. Nero, for one, became a fervent Greens fan in childhood. Four hundred years later, Justinian’s predecessor Anastasius endorsed a theological argument popular with the lower classes, leading some historians to assume that he too supported the Greens. “It is thus unfortunate that he should have turned out not to be a Green,” wrote the historian Alan Cameron in 1976. “Alas! He was a Red.” Toward the end of the twentieth century, historians have increasingly rejected the idea that Roman or Byzantine chariot-racing fans went to the Hippodrome to express political views. Cameron concluded, “The truth is (of course) that Blues hated Greens, not because they were lower-class or heretics—but simply because they were Greens.”

Curse tablets inscribed with invective that targets charioteers by team and name paint a vivid picture of just how much animosity flew between the teams. Roughly eighty of these credit-card-sized lead tablets have been found, making them one of the most frequently attested genres of Roman curses. “I invoke you, whoever you are, spirit of the dead,” one curse from Carthage begins, “in order that you serve me in the circus on the eighth of November.” After naming several charioteers for the Reds—aligned, as a sort of minor-league franchise, with the more elite Blues—the curse continues:

Torture their thoughts, their minds, and their senses so that they do not know what they are doing. Pluck out their eyes so that they cannot see, neither they nor their horses which they are about to drive.

Another tablet threatens Blue team drivers in the Syrian city of Apamea with insomnia and hunger in the days leading up to a particular race. If that weren’t enough, the curse also wishes that the ghosts of people who died prematurely or violently commit to haunting the starting gates of the circus on the day of, spooking the Blue charioteers and their horses.

Geographically and chronologically, the curses are concentrated in the boomtown frontiers of North Africa and the rich cities of the eastern provinces between the third and fifth centuries, but examples have been found scattered across the Mediterranean; one tablet written in an exclusively Jewish dialect of Aramaic proves that the practice crossed cultural lines (for the record, the Jewish curser, who lived during the fifth or sixth century, supported the Greens). Still, the curses have much in common. In general, the curses begin with a ritual invocation to a supernatural being (usually daimones or infernal spirits), who is then given specific instructions for sabotaging a named charioteer during an upcoming race. Meddling with the eyesight of the charioteer or his horse was an especially popular request, as was knocking the chariot over when it made a dangerous turn.

The curses also share archaeological contexts. They were often buried in cemeteries in order to benefit from what historian Florent Heintz has called the “infernal postal system”: In Roman superstition, human and animal remains constituted a sort of nexus between the world of the living and the world where ghosts and demons resided. Like a letter, the curse tablets would never reach their intended infernal recipients unless the proper posthumous postage was attached. Charioteer curses have also been found inside stadiums, underneath the racetrack; when this was the case, the tablet was often accompanied by an animal corpse (one curse-instruction manual from Egypt recommends stuffing a gutted cat with curse tablets; such a ritual ensured that the cat’s presumably angry spirit would harass the charioteer and his horses at the starting gate).

Due to their consistency, the tablets are believed to have been produced by professional magicians who could be hired to customize a curse for any situation.1 Exactly who was commissioning these curses is more controversial: popular theories have included individual charioteers, team owners, gamblers, and overenthusiastic fans. None of these interpretations is mutually exclusive; all four categories of people may have visited magicians for the purpose of sabotaging a race. If so, two different motivations must have existed. Whereas the charioteers, their managers, and heavy gamblers all would have had significant financial interest in rigging a game, for the zealous fan a curse was a powerful, if secret, way to support a favorite team—or, rather, and perhaps more importantly, to express resentment for their rival.

An analogue in contemporary sports can serve as food for thought, if not actual historical evidence: in several cases of “cursed” objects buried underneath professional sports arenas, the perpetrators were lone-wolf fans rather than players, management, or career gamblers. Ten years ago, a souvenir jersey emblazoned with the name and number of Boston Red Sox designated hitter David Ortiz, better known as Big Papi, was submerged in the fresh foundation of the new Yankees Stadium, which has been described as having a facade that echoes the Roman Colosseum. Players on both teams found it mildly funny; reached for comment, Ortiz simply said, “I don’t pay attention to any of this.” Yankees management took things more seriously, shelling out $50,000 to extract the shirt from hardened concrete in order to undo what Yankees president Randy Levine called a “dastardly act” and pursuing criminal charges against the perpetrator, construction worker Gino Castignoli. (The case was tossed out by the Bronx district attorney, a Mets fan.)

For his part, Castignoli vacillated between laughing the curse off—“Anybody with half a brain knows it was all done in fun. I didn’t hurt nobody”—and proudly recounting the methodical way he pulled it off. Despite having originally turned down a job working as a cement mason on the project (“I would not go near Yankee Stadium for all the hot dogs in the world”), Castignoli changed his mind when he realized it would afford him intimate access to the home turf of the team he so viscerally hated. “As I stuck [the jersey] in,” he told the New York Post, “I said, ‘The Yankees are done for the next thirty years.’ I only put a thirty-year curse because I’m forty-six and in thirty years I’ll be dead, and I won’t care if the Yankees win then.” Castignoli quit the following day, his mission accomplished.

Like the Washington Capitals hockey puck hidden underneath the Pittsburgh Penguins arena in 2009 and the flag bearing the Kansas City Chiefs logo buried under the construction site of the new Las Vegas Raiders stadium in 2017, Castignoli’s Red Sox jersey is not an object believed to have the power to invoke and control literal demons. Even taking into consideration the remarkable persistence of superstition in American professional sports, most fans would be hard-pressed to see the burial of one team’s memorabilia underneath another’s stadium as anything worse than a symbolic desecration: insulting, but not actually dangerous.

For Romans, on the other hand, curses in the stadium were a deadly serious matter. By the early fifth century, a law existed ordering that any person caught digging in the sand of Constantinople’s racetrack after dark be arrested and tried as a magician. Charioteers carried amulets meant to ward off curses during races.

And yet the curses kept coming. In an attempt to articulate the logic of these irrational attempts at sabotage, John R. Gager, the editor of the authoritative English-language publication on ancient lead curse tablets, wrote that they were a technology that allowed everyday people to tap into “a world of gods, spirits, and daimones...a world where emperors, senators, and bishops were not in command.”

Also excluded from command in the world of curses? Athletes. The torments described in the curses would negate any amount of talent and training in the victim. Likewise, any charioteer who benefited from a curse (whether because he was its mastermind or merely because he wasn’t the target) was participating in a rigged contest, dependent on the cooperation of demonic spirits. Not that any of the charioteers seem to have minded; according to ancient sources, black magic in chariot racing was as endemic—and as much of an arms race—as doping has been in contemporary professional sports. “Among charioteers,” the sixth-century statesman Cassiodorus writes of an athlete accused of sorcery, “it is seen as a great honor to attain to such accusations.”2

The name given to the 532 riot, taken from the chant shouted by the rioters, Nika! Nika! (meaning “Victory! Victory!”), is, not coincidentally, a direct reference to racecourse culture. A common refrain in the Hippodrome stands, the cheer was reserved for a charioteer of one’s chosen faction—perhaps the very charioteer whose rivals one had cursed. By shouting it together during the riot, Blue and Green fans declared themselves on the same team for the first time. Their opponent was now the emperor himself, whose attempt to quash the Blue-Green rivalry through state violence had, in a way, worked. United against Justinian in 532, partisans of the Blues and the Greens set aside their mutual hatred to fight and die for a higher, shared principle: their inalienable right to rebuke good sportsmanship, play dirty, and lose poorly.

1 This type of black magic does not seem to have been cost-prohibitive. A woman in third-century Britain, for example, purchased a curse tablet targeted at a thief who had stolen two silver coins from her. As John Gager notes, it’s reasonable to assume that at least some curses cost less than the value of her lost money (which would have bought her about two eggs at the market). ↩

2 Not all fans saw curse-assisted victory as legitimate. “When you believe that a charioteer or a horse has been hobbled in this manner, everything is in an uproar, as if the city itself had been destroyed,” the fourth-century rhetoric teacher Libanius scolded his students after finding himself the target of a similar curse aimed at damaging his health, “but I am treated with indifference when the same things happen to me.” ↩