The Gulf Stream, by Winslow Homer, 1899. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Catharine Lorillard Wolfe Collection, Wolfe Fund, 1906.

In college a professor once pointed to a map, describing how the names of certain towns in Ohio could awaken knowledge in us even if we never left campus: Sparta, Monticello, Africa. Just a few miles from Kenyon College was the Knox County seat, Mount Vernon, named for George Washington’s Virginia slave plantation on the banks of the Potomac. Dan Emmett, founder of one of the first troupes of the blackface minstrel tradition and often credited with the Confederate ballad “Dixie,” was born in Mount Vernon in 1815. His home still stands. Even in the North we were in the heart of Dixie—even, yes, in 2008.

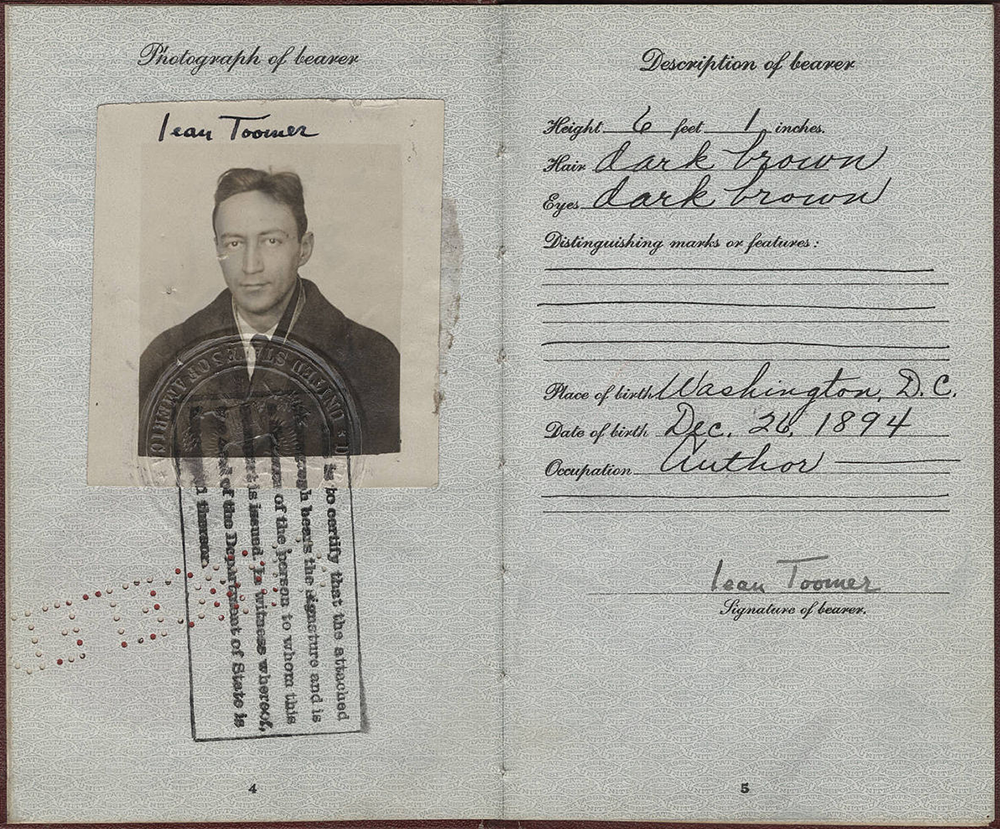

The professor’s syllabus included a novel called Cane by Jean Toomer. I spent long nights reading that book, written nearly a century earlier, and attempting to decipher Toomer’s personal history. Centered on racial violence and anxieties in the United States, Cane derives from Toomer’s experiences as a substitute principal at Sparta Agricultural and Industrial Institute in Georgia in the fall of 1921. The text, which mixes modernist poetry, song, and autobiographical fiction, is often described as being as unclassifiable as its author. Toomer, variously identified by others as white, black, or Native American, thought of himself as an “American, neither black nor white, rejecting these divisions, accepting all people as people.”

Toomer’s Cane was hailed as a critical success when it appeared in 1923. William Stanley Braithwaite wrote, “Jean Toomer is a bright morning star of a new day of the race in literature,” and Countee Cullen described Cane as a “real race contribution, a classical portrayal of things as they are.” But Toomer would not allow Cane to be excerpted in black anthologies. He wished to withdraw his work “from all things which emphasize or tend to emphasize racial or cultural divisions.” Toomer attempted to initiate a post-racial America nearly a century before my naive college classmates—and much of the rest of the country—debated whether we had achieved the dream with Barack Obama’s election to the presidency in 2008.

How does this 1920s novel hewn from reflections on racial terrorism remain so terribly relevant, and how do those who worship whiteness continue to sow and feed on fear? Toomer is one of American literature’s greatest enigmas and Cane one of our finest texts. What Toomer bore witness to in Cane is America’s waking nightmare. Cane is our living inheritance.

Jean Toomer was born Nathan Pinchback Toomer in Washington, DC, in 1894, named for the father who would soon abandon him. As his son would, Nathan Toomer Sr. lived a dual existence as a man understood as either white or black depending on the circumstances. Toomer’s maternal grandfather knew his son-in-law wasn’t a good man; wishing to erase any mark, he changed his grandson’s name to Eugene Pinchback. The boy was known as Pinchy to his neighborhood friends, Snootze to his uncles. P.B.S. Pinchback, a leading Reconstruction-era politician in Louisiana, is remembered for being the first black governor of any state in the Union. Toomer’s grandfather had a way with names: he had named his sons after Bismarck and Napoleon. His daughter Nina was named for her mother, just as my great-grandparents, fellow members of Washington’s light-skinned elite, named two of their children, Andrew and Carlotta, after themselves. Repetition of names or events, writes Gayl Jones in an essay on Cane, “contains energy and sustains movement…and enlarges the parameters of experience and implication.” Repetition mobilizes significance from one world to another, from one consciousness to another. Naming as repetition is metempsychosis, so that when my grandmother calls me by name she also divines her brother Andrew and her father. “Repetitions,” Jones continues, “give a flexible sense of time that may be contracted, stretched, bent in successive generations.” Naming is an assurance that the past is brought to bear in the present, despite what either might hold.

For Toomer, this came to mean facing a history we wish to forget, a past that recurs. When it came time to write his masterpiece, he chose a title that simultaneously signified the sugarcane once harvested in Georgia and the biblical story of the mark of Cain, a tale used by whites to defend their myth of racial supremacy.

One evening in Georgia in 1921, Toomer took up a stalk of sugarcane and began whittling. In his pocket notebook that night he recorded, “I am not a failure. No, not yet.” Perhaps this is when the doubled meaning struck. “That stalk of cane,” writes Barbara Foley, author of Jean Toomer: Race, Repression, and Revolution, “symbolically encompassing prophetic meanings, would constitute Toomer’s bid for fame.”

It was the end of King Cotton’s reign when Toomer left Washington, DC, for Sparta. For Toomer, disembarking from a train car in Georgia wasn’t a step back into the past but a fraught introduction into the terrible immediate present, the continuous moment of deaths and near-death experiences awaiting African-descended peoples in the U.S. He entered a world where his ancestors had enslaved and been enslaved; Georgia then held the record for rural lynchings. Here were ritualized killings: disappeared men, drownings, and “burning fests” where pregnant mothers were burned alive and their unborn children ripped from their wombs and snuffed out—a place of death farms and untold violence. Tufts professor Christina Sharpe calls this history, a history we live and die with, “weather.”

It is weather, and even if the country, every country, any country, tries to forget and even if “every tree and grass blade [of the place] dies,” it is the atmosphere: slave law transformed into lynch law, into Jim and Jane Crow, and other administrative logics that remember the brutal conditions of enslavement after the event of slavery supposedly came to an end…When the only certainty is the weather that produces a pervasive climate of anti-blackness, what must we know in order to move through these environments in which the push is always toward black death?

Ralph Kabnis, a light-complexioned aspiring writer and a protagonist of Cane, has come South to teach. In an undated letter, Toomer claimed, “Kabnis is me.” His is a story of fear, ignorance, denial, revelation, and coming to terms with suppressed memories of a past some seek to ignore.

While reading in his cabin one evening before bed, Kabnis begins talking to himself.

If I could feel that I came to the South to face it. If I, the dream (not what is weak and afraid in me) could become the face of the South. How my lips would sing for it, my songs being the lips of its Soul. Soul hell. There aint no such thing. What in hell was that?

Sudden noises from outside his cabin stir Kabnis’ deepest fears: “Something as sure as fate was going to happen.” He has every reason to be afraid: he is a black man, however light-skinned, living in a violent, racist country. He envisions himself dragged from his cabin and apprehended by whites: “He sees white minds, with indolent assumption, juggle justice and a nigger.” The weather of the place gives Kabnis reason to fear.

Cane is a novel about life in the wake of black death. “Lynching,” writes Charles Scruggs and Lee Vandemarr in Jean Toomer and the Terrors of American History, “is central to Cane, as violent fact and as whispered fear, reflecting both the society of the New South—where, after 1880, in the words of one contemporary observer, it became ‘a popular sport’—and the precise historical situation in Georgia.”

In 1915, six years before Toomer arrived in Sparta, a black citizen named Daniel Barber resisted arrest after being accused of bootlegging liquor. The police eventually took Barber and his entire family—he and his wife had two sons and a daughter—into custody. A mob stormed the jail. Barber was forced to watch his children hang, one by one, before they hanged him too. Dozens of African-descended citizens were hanged in Georgia in the years prior to Toomer’s trip to the South. Stories of lynching and ritual violence occur throughout Cane, including that of Mame Lamkins, a character drawn from a heinous incident: when a pregnant Georgia woman tried to protect her husband from a lynch mob, she and her unborn child were murdered. The weather of the place is defined by repetitions of such ritualistic violence.

A local named Layman befriends Kabnis. When Kabnis pushes to learn more about the South’s history of racial terrorism, Layman tells him, “Mr. Kabnis, kindly remember youre in th land of cotton—hell of a land. Th white folks get the boll; th niggers get the stalk. And don’t you dare touch th boll, or even look at it. They’ll swing you sho.”

“Nigger’s a nigger down this way, Professor,” Layman adds. The implication is that Kabnis, who takes pride in being light-complexioned, may not grasp how little white-supremacist mobs care about slight class or color differences within the black community. Kabnis, who proudly states that his ancestors were Southern blue bloods (mixed-race people so light-skinned you could see the color of their veins, perhaps even indistinguishable from whites), may have looked quite a bit like his creator. Toomer, as a cousin of mine likes to say of some of our people, “could pass for just about anything.” Throughout most of his life—with the exception of the time he spent composing Cane—Toomer expressed a deep ambivalence about his racial heritage.

Toomer felt that, privileged by his ambiguous appearance, he could see equally into lives both black and white. He could claim, as Kabnis tries to, that he was of no particular race. To counter this position, Toomer provides a foil in the character of Lewis, who “is what a stronger Kabnis might have been, and in an odd faint way resembles him.” When Kabnis describes his people as being Southern blue bloods, Lewis catches the implied denial of his racial past. Lewis describes Father John, a blind elderly freedman sitting with them, as “symbol, flesh, and spirit of the past, what do you think he would say if he could see you? You look at him Kabnis.” A drunk Kabnis does not want to look:

Kabnis: Oh, hell…he reminds me of that black cockroach over yonder. An besides, he aint my past. My ancestors were Southern blue-bloods—

Lewis: And black.

Kabnis: Aint much difference between blue and black.

Lewis: Enough to draw a denial from you. Cant hold them, can you? Master; slave. Soil; and the overarching heavens. Dusk; dawn. They fight and bastardize you.

Lewis realizes that Kabnis, despite the nonchalance he feigns in the face of Southern lynch law, is fearful not only of the weather of Sparta but also of his personal history. Kabnis denies the pasts of his present; he seeks to hold himself above and apart from the black slaves he is descended from. He wishes to inoculate himself against his fears of being threatened or worse by racist whites, but Kabnis will never become the face of the South unless he can accept and derive strength from the truths of his ancestral past.

Toomer never wrote anything else comparable to Cane. In his 1940 autobiography, The Big Sea, published seventeen years after Cane, Langston Hughes described Toomer, then only in his early forties, as having given up writing about the experiences of black Americans in favor of practicing a New Age spiritualism developed by an Armenian named George Gurdjieff. Thus, writes Hughes,

the Negroes lost one of the most talented of all their writers—the author of the beautiful book of prose and verse, Cane…Harlem is sorry he stopped writing. He was a fine American writer. But when we get as democratic in America as we pretend we are on days when we wish to shame Hitler, nobody will bother much about anybody’s race anyways.

Hughes claims Toomer went “silent.” Others say that after the publication of Cane, wherein he used black history and folklife to his own artistic and personal advantage, Toomer never again so closely associated with the black community—he disappeared into the white world. He would not have been alone.

Thirty-one years before Toomer’s birth, during the middle of the Civil War, Grandfather Pinchback received a letter postmarked Sidney, Ohio. The letter was from Pinchback’s sister Adeline, Toomer’s great-aunt. She warns her brother—who lived as a black man though he was often mistaken for Andrew Carnegie—that he should erase the mark of his blackness. He should, like Adeline had, become white:

If I were you Pink I would not let my ambitions die. I would seek to rise and not in that class either but I would take my position in the world as a white man as you are and let the other go for be assured of this as the other you will never get rights. Know this that mobs are constantly breaking out in different parts of the north and even in Canada against the oppressed colored race. Right in Cincinnati they can hardly walk the streets but they are attacked…Reuben established his position here as a white man, voted as one and volunteered in the services of the country as one. He was insulted by the negroes here right at the public hotel and called every insulting name…I have nothing to do with the negroes am not one of them. Take my advise dear brother and do the same.

Even in Ohio, even in the North—in 1863, in 2008, or 2017—we are in Dixie. This is the weather. Adeline’s letter is a devastating admission of the fear whiteness feeds upon. A retreat into this state of antagonism afforded Jean Toomer’s great-aunt protection and privilege she may never have otherwise known. She absolves herself of any responsibility to black Americans, insists she has “nothing to do with the negroes am not one of them,” but signs the letter “Your loving sister.” Yet despite her advice her brother chose to identify with the struggle of African-descended citizens in the United States. Pinchback gave the letter to Toomer, who kept it until his own death, in 1967, more than a century after his great-aunt sent it. The letter is now held in the Beinecke Rare Books and Manuscripts Library at Yale University, which also includes a 1934 letter in Toomer’s hand wherein he shuts his talent to the world: to an inquiring anthologist Toomer insists, repeating his great-aunt’s assertion, “I am not a Negro.”

I took the train north to New Haven one evening this spring. I had just read Cane for the first time as an adult, no longer in college. I am now twenty-seven, the age Toomer was when he wrote his masterpiece. I thought of how Toomer drafted Cane on trains returning to Washington from Georgia—did he sit in the black car or the white car?—and how he might have timed the rhythms of his words to the ringing of the rails, striking downhome talk and folksong into modernist poetry. I caught the reflection of my white-looking features in the train window and wondered at how my appearance eases me through time. How so many of my people have lit out for whiteness, never to return. My “white” Mormon cousins out West. Would there come a time, even worse weather, when I too might deny my past? I remembered my enslaved ancestors, their courage, the land they purchased when freed by the Union forces. At the Yale library, reading through papers Toomer kept during his time in Sparta and in his later time of exile, I witnessed how pain and fear—of the world, of one’s self—could be twisted into a terrible, haunting beauty.