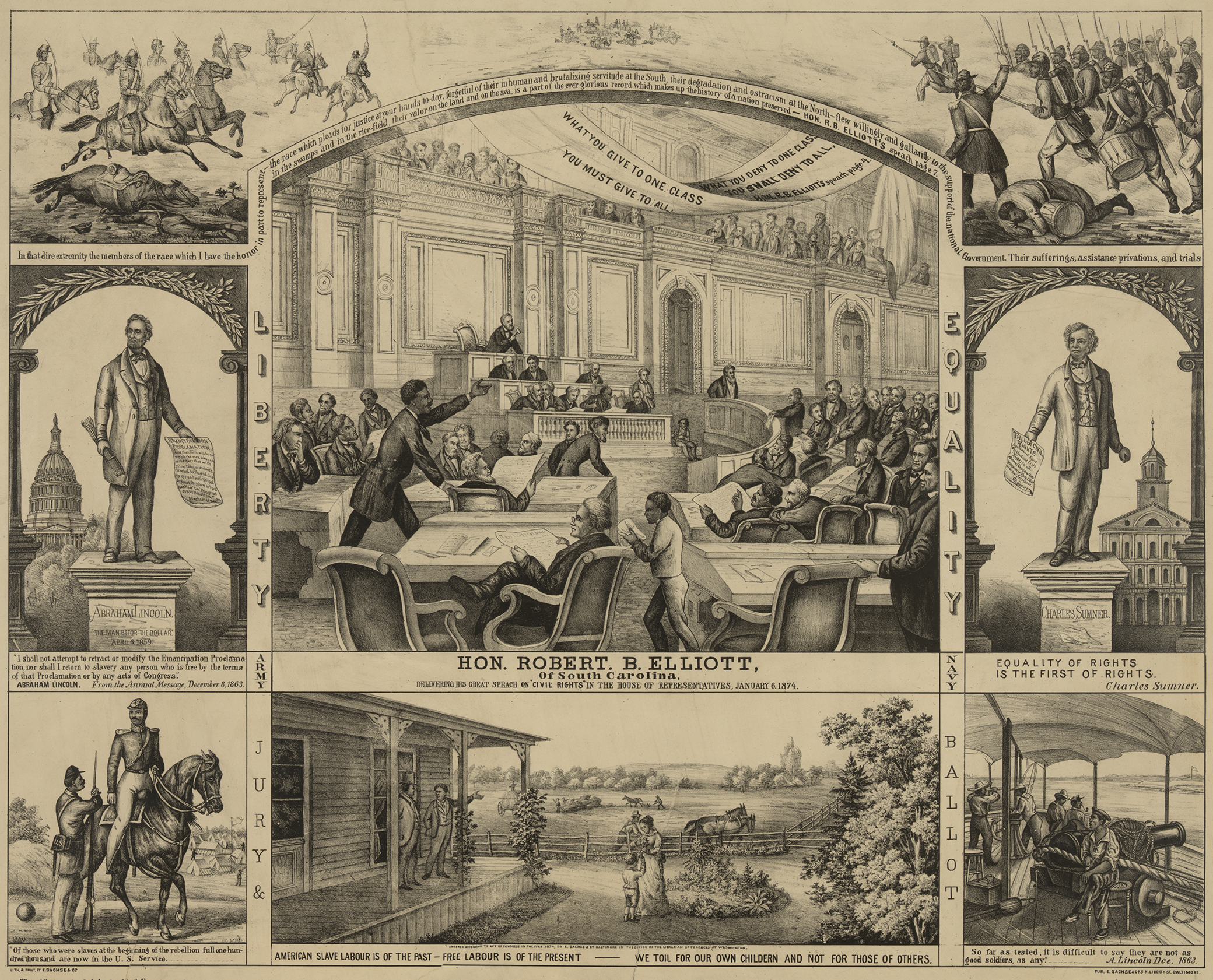

The Shackle Broken—By the Genius of Freedom, by E. Sachse & Co., c. 1874. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

Graduating from the University of South Carolina in 1877 with a degree signed by Governor Wade Hampton, who had served as an officer in the Confederate army and owned slaves, Cornelius Chapman Scott tried to make a decent life for himself under difficult circumstances. Scott worked in upstate South Carolina as a public school teacher and Methodist preacher, striving to help the most vulnerable members of the state’s African American community cope with the new realities. But in the spring of 1880, the well-educated, well-to-do, mixed-race Charlestonian caught a glimpse of the apocalypse.

A local theater was presenting the biblical Book of Revelation through a panorama—a high-tech, immersive, virtual reality conjured by a moving set with simultaneous narration. Hearing good reviews, Scott was eager to watch the four horsemen rampage across the palm-bedecked, subtropical landscape. On a springtime Thursday night, Scott arrived at the Greenville Opera House box office and paid his fifty cents for a ticket. Seating at the theater had long ago been desegregated, so Scott was taken aback to receive a “half-ticket” entitling him to a balcony seat and twenty-five cents in change. He insisted he wanted a “full ticket” and, after pushing his half ticket and twenty-five cents back to the clerk, he was given one.

But when Scott took his assigned seat, a white man approached, pointed to the balcony, and instructed, “The gallery is for colored people.” Scott stayed put. As the music began and the panorama commenced, Scott again thought the matter resolved. But midway through the show, a policeman arrived—“a contemptible ‘poor white trash’ who look[ed] more like a colored than a white man,” as Scott later recalled—and tried to remove him by force. Scott refused to move, telling the officer that he could arrest him, but he would not comply voluntarily nor would he physically resist. Only when the policeman grabbed Scott by the shoulders did he budge. As Scott was escorted through the theater lobby, the management attempted to refund his money but, to show he was leaving against his will, Scott refused. “I was now sick of the thing,” Scott recounted soon after in a letter to his father. “I was boiling with indignation, but kept perfectly cool.” No matter how bad things were in South Carolina, Scott knew he could bring a case under the federal Civil Rights Act of 1875. Scott had done everything a civil rights plaintiff should do to win a case—not leave voluntarily, not resist the police, and not accept a refund—but when he approached an attorney, the lawyer was dubious. Trying to recover money from the policeman would be hopeless as he almost certainly had no savings, but suing the Greenville Opera House raised other problems. One of its owners was a county official. And justice was anything but blind in the now “redeemed” State of South Carolina, especially upstate.

“I shall not undertake to bring an action against them,” Scott concluded, “unless I could have the case take place in Charleston.” But even a victory in a federal courtroom in Charleston would face hostility at every step of appeal. Despite all the civil rights laws on the books, an ominous warning shot had come down from Washington, DC, in 1878. In a unanimous decision, the Supreme Court invalidated a landmark transportation discrimination case: Josephine DeCuir’s $1,000 recovery from the Louisiana riverboat that had barred her from the “ladies’ cabin.”

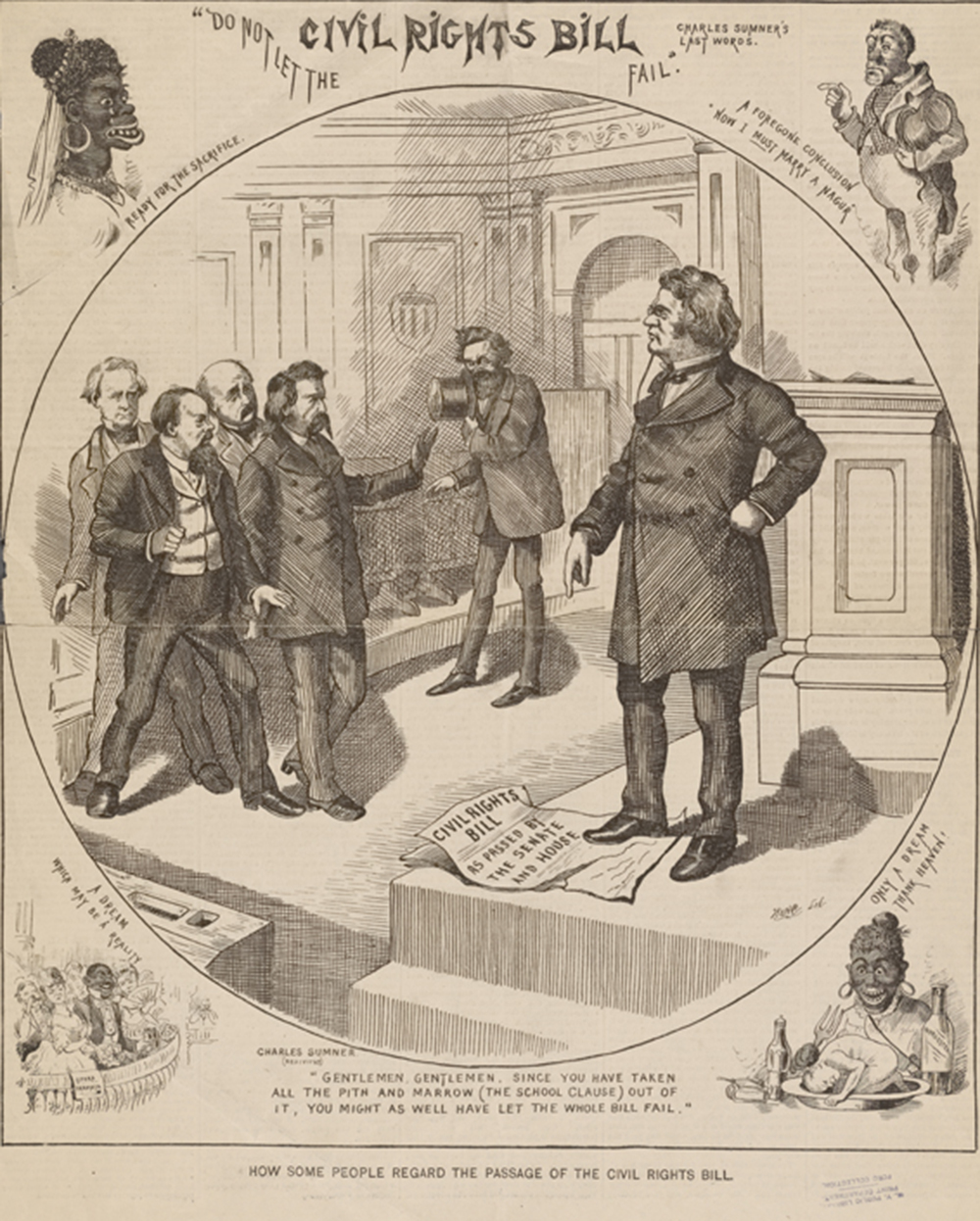

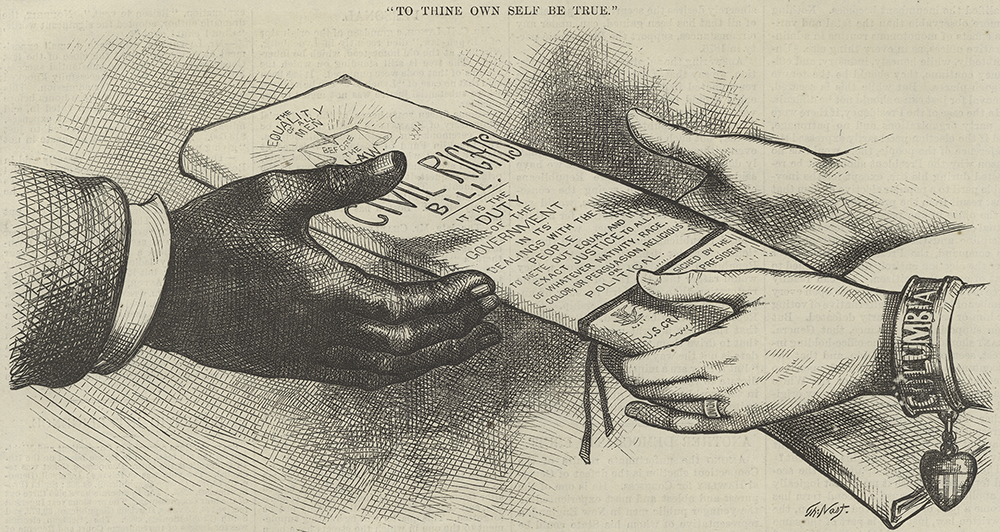

The high court’s reasoning was bizarre. The decision, authored by Chief Justice Morrison Remick Waite, argued that because the vessel’s full route crossed state lines, journeying upriver to a final destination of Vicksburg, Mississippi, it should be considered interstate commerce even though DeCuir had bought an in-state ticket from New Orleans to Hermitage, Louisiana. Being interstate commerce, only Congress, not a state legislature, could regulate it; thus Louisiana’s civil rights statute had no bearing on DeCuir’s journey. “If the public good requires such legislation,” the elderly Northerner wrote for the unanimous court, “it must come from Congress and not from the states.” But in the time between the 1872 incident and the 1878 Supreme Court decision, Congress had taken this very action. In 1875 it had passed Charles Sumner’s Civil Rights Act, which stipulated clearly that “all persons within the jurisdiction of the United States shall be entitled to the full and equal enjoyment of…public conveyances on land or water…applicable alike to citizens of every race and color.” The decision read as if Sumner’s law had not passed, never suggesting that plaintiffs in similar situations could now sue in federal court under the 1875 civil rights law.

In 1883 the Supreme Court fully revoked federal support. In a consolidation of five lawsuits that became known as the Civil Rights Cases, the Supreme Court struck down the Civil Rights Act of 1875 as unconstitutional. In all five cases, African Americans refused the use of public accommodations guaranteed to them by Senator Sumner’s law had pressed federal charges against the proprietors. Notably, only one of the cases originated in the South—that of a Tennessee railroad conductor who had attempted to physically push an African American woman out of a whites-only railcar. He only backed down when the fair-skinned, blue-eyed man who had boarded with the woman outed himself as her nephew and firmly requested that the conductor cease manhandling his aunt. The Midwest cases concerned a Kansas restaurateur and a Missouri innkeeper who refused to serve black patrons. The most famous of the cases came out of San Francisco and Manhattan, where recalcitrant theater owners had refused to seat black ticket holders despite the federal law. In the San Francisco case, a black man was refused a seat at a minstrel show at Maguire’s New Theater on Bush Street in 1876. In the New York case, a South Carolina transplant was denied a seat at the Grand Opera House in 1879 at a tragedy starring Edwin Booth, the brother of the man who had shot President Lincoln.

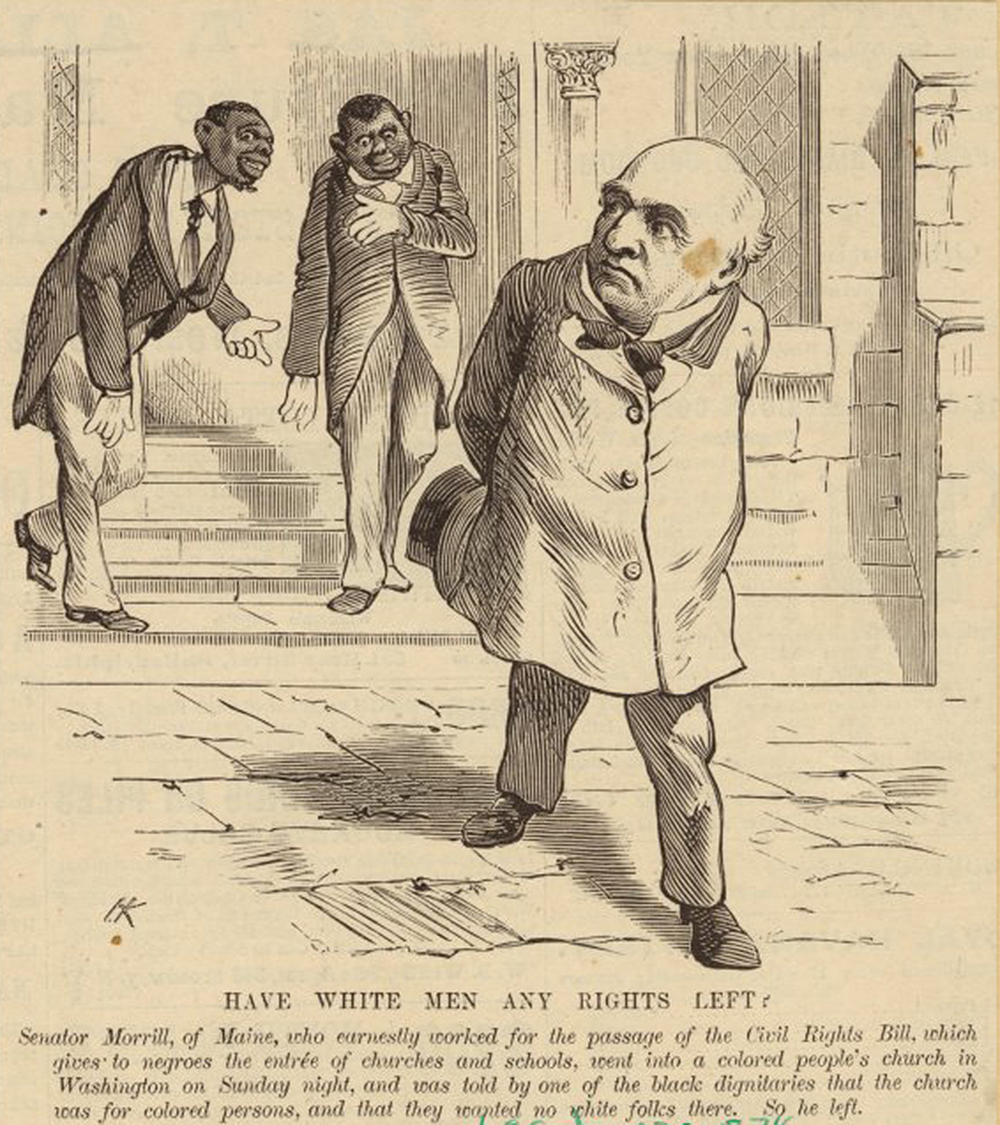

As the cases headed towards the Supreme Court, public support for civil rights continued to erode. In an 1879 editorial, the New York Times sneered that

to invoke the Civil Rights laws is becoming very fashionable. Within a few days a holder of a ticket to an uptown theater was refused his seat on account of color, and he threatens a civil rights action. Not many weeks ago a colored clergyman called for refreshments at an ice cream saloon in Jersey City; the proprietor refused to serve him, and at last reports he was consulting a lawyer about suing under the Civil Rights laws. At the South, two or three married couples have lately been prosecuted because, contrary to the law of the State, the husband was black and the wife white, and their lawyers have argued that such law amounted to nothing, because [it is] contrary to the Civil Rights laws. At the North, when the Jews are excluded from Saratoga or Coney Island hotels, they are counseled that by virtue of the Civil Rights laws they can insist on being received…What are these ‘Civil Rights laws’?…If a [businessman] does not wish to employ negroes, or…sell to negroes, there [ought be] no compulsion.

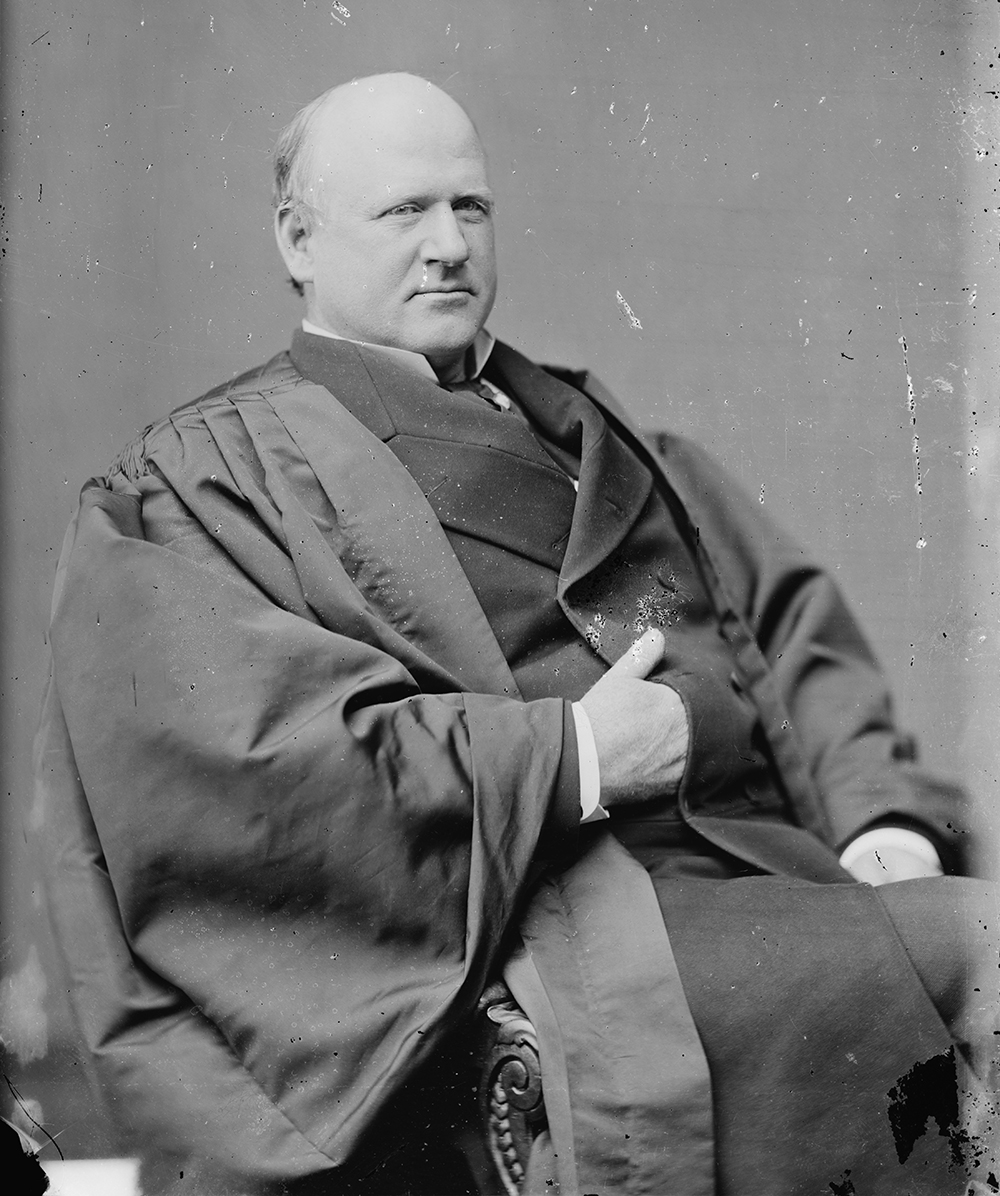

It was in this hostile climate that the Supreme Court heard the cases and issued its eight-to-one decision striking down the Civil Rights Act of 1875. Writing for the majority, New York native Justice Joseph Bradley explained that the federal government lacked the authority to prevent “every act of discrimination which a person may see fit to make as to the guests he will entertain, or as to the people he will take into his coach or cab or car, or admit to his concert or theater, or deal with in other matters of intercourse or business.” In the high court’s view, the federal requirement that a theater owner must seat African American ticket holders was tantamount to forcing him to host black guests at his house for dinner. But in the decision’s most stunning section, Bradley condescendingly told African Americans to quit whining. “When a man has emerged from slavery,” he scolded, “there must be some stage in the progress of his elevation when he takes the rank of a mere citizen and ceases to be the special favorite of the laws.” Bradley’s opinion conflated all African Americans with freedmen regardless of whether they had ever been enslaved and insisted that, despite this, the state owed them nothing—not even equal rights.

Only a single justice, John Marshall Harlan, dissented. Born to a slaveholding family in Kentucky, Harlan seemed an unlikely defender of civil rights. But, like many Southerners of his class, Harlan was part of a multiracial family—he had a mixed-race half sibling—and, unlike many Southerners of his class, Harlan’s half sibling was acknowledged by his family. Young John’s blue-eyed, straight-haired, enslaved half brother Robert, born to one of the family’s mixed-race slave women, was sent to the same whites-only elementary school as the rest of the children until he was outed by a janitor as a child of color and expelled. Reaching adulthood, Robert’s father-owner had him live independently and encouraged him to open a barbershop and grocery store in Lexington. In 1848, Robert, though still legally his father’s property, moved west to California, where he made a fortune. Returning home wealthier than his father, Robert bought his freedom from him for five hundred dollars and settled in Cincinnati, where he opened several businesses and married a white woman. Perhaps because Justice Harlan was loath to sentence his half brother to a lifetime of discrimination, he cast the only vote on the Supreme Court to uphold the Civil Rights Act of 1875.

In his dissent, Harlan did not mention his multiracial family, but he did call out his colleagues for using word games to subvert the will of Congress. “I cannot resist the conclusion that the substance and spirit of the recent amendments of the Constitution have been sacrificed by a subtle and ingenious verbal criticism,” Harlan wrote. “The court has departed from the familiar rule requiring, in the interpretation of constitutional provisions, that full effect be given to the intent with which they were adopted.” Whatever Justice Bradley had written, equal rights were not special rights:

My brethren say that, when a man has emerged from slavery…there must be some stage in the progress of his elevation when he takes the rank of a mere citizen, and ceases to be the special favorite of the laws…It is, I submit, scarcely just to say that the colored race has been the special favorite of the laws. The statute of 1875, now adjudged to be unconstitutional, is for the benefit of citizens of every race and color. What the nation, through Congress, has sought to accomplish in reference to that race is what had already been done in every State of the Union for the white race—to secure and protect rights belonging to them as freemen and citizens, nothing more.

Harlan directed his dissent to his metaphorical “brethren” on the Supreme Court in Washington but, as he was making this argument, how could he not have been thinking also of his biological half brother John in Cincinnati?

White supremacists nationwide hailed the Supreme Court’s nearly unanimous decision. At the Atlanta Opera House, the management interrupted a minstrel show to announce the news from Washington. For the theater managers, the decision was no academic matter; a case against the venue, challenging its segregated seating policy, was working its way through the courts. Now the highest court in the land had, essentially, invalidated the suit. The civil rights–weary New York Times reported on the “wild scene in the [Atlanta] opera house last night when the announcement of the civil rights decision was made…While [white] men stood on their feet and cheered and ladies gave approving smiles, the quietude of the colored gallery was noticeable. Not a note of applause came from those solemn rows of benches; their occupants were dumbfounded.” The Atlanta Constitution crowed the news from Washington with alliterative abandon: “A Radical Relic Rubbed Out.” It was left to an African American paper in Harlan’s home state, the Louisville Bulletin, to assail the Supreme Court’s logic, editorializing bluntly: “Our government is a farce.”

Excerpted from The Accident of Color: A Story of Race in Reconstruction by Daniel Brook. Copyright © 2019 by Daniel Brook. Used with permission of the publisher, W.W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.