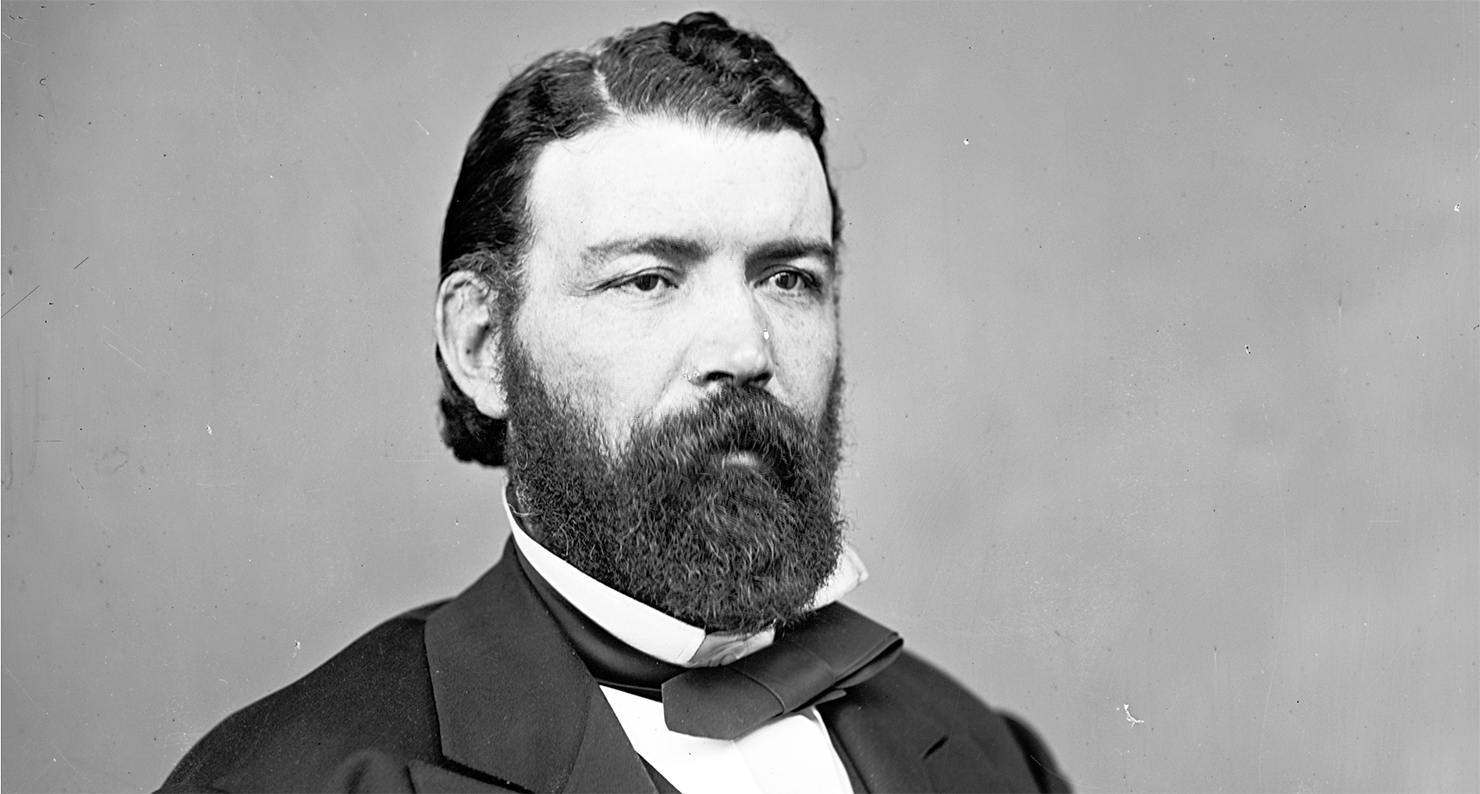

John Morrissey, U.S. Representative from New York, c. 1867. Photograph by Mathew Brady. United States Library of Congress. Also known as Old Smoke, Morrissey was an Irish American bare-knuckle boxer and a gang member in New York in the 1850s before becoming a congressman from New York in 1867.

“You can’t be a half a gangster,” proclaims the tagline of Boardwalk Empire’s third season. One of the implications, besides the obvious ones for protagonist Enoch “Nucky” Thompson’s soul, as well as his career trajectory, is that the position of the politician and businessman who just happens to be a mobster is under threat. You can be a gangster, or you can be legit, but not both.

This contradiction is best exemplified by Thompson (played by Steve Buscemi), county treasurer and boss of Atlantic City, whose finger is in every pie and whose velvet glove is on every throat. Thompson’s Irish-American heritage is not always foregrounded, and, indeed, his connection to his ethnic background seems grudging, disdainful, and often related to deep emotional pain. However, he courts the Ancient Order of Hibernians (an Irish-Catholic fraternal organization), gives freely, more or less, to Sinn Fèin, and his Atlantic City is so Irish-controlled that bootlegger Mieczyslaw Kuzik changes his name to “Mickey Doyle” to better fit in. The importance of Thompson’s heritage and identity ties into the fact that the mobster/politician/businessman is a distinctively Irish-American character with a long and twisted history.

The concept of the mob boss was invented in the Five Points, the infamous slum in the lower Manhattan of the 19th Century. The name comes from a mob primary, wherein a candidate for public office would hold forth, gathering a large crowd which would, in exchange for food, drink, or shelter, agree to vote for him. Isaiah Rynders, an early figure in Tammany Hall’s development who helped elect James K. Polk president, exemplified the type. Rynders was succeeded by the Tipperary-born John Morrissey. Herding new Irish immigrants toward free room and board in exchange for promises of electoral support, Morrissey rose fast, buying into a saloon and establishing himself as a well-known professional bare-knuckle boxer, two important steps to forming a solid political bloc. Morrissey’s fame only grew after involvement in the killing of Bill “The Butcher” Poole, a hated Natvist and Know-Nothing gang leader, as well as the basis for Daniel Day-Lewis’ character in Gangs of New York, the first in Martin Scorsese’s late-period obsession with the Irish-American underworld (encompassing The Departed and Shutter Island as well as Boardwalk Empire).

Realizing that without a formal political title, he’d always be considered just another thug, Morrissey, who by then was known as “Old Smoke”, got himself elected to Congress in 1868 and soon became Tammany Hall’s Celtic point-of-contact. This proved a repetition, though a significantly higher-class one, of his first job in New York City. Old Smoke got the Irish vote out, and their soaring numbers kept Tammany in power, no matter how much it was bilking. Tammany’s demise in the 1870s precipitated Morrissey’s, and he died, of drink and head-trauma induced dementia, at 47. Though disgraced, Morrissey offered the prototype of the Irish-American as mobster/politician/businessman, demonstrating how the three identities were inextricably linked.

Born ten years after Morrissey’s death in 1878, Joseph Kennedy, the son of a famine immigrant from Wexford turned Massachusetts senator, inherited both cash and contacts in the local liquor industry. After the Volstead Act of 1919 created Prohibition, Kennedy proceeded to invest the former in the latter, becoming an importer and wholesaler of Scotch, at one point the largest in the nation. While bootleggers abounded during Prohibition, the number of large-scale operators was small, and Kennedy, by necessity, had to work with such figures as Al Capone and Frank Costello, who was allied with Lucky Luciano and Meyer Lansky (both of whom appear as characters on Boardwalk Empire).

These mob contacts served Kennedy throughout his subsequent careers in film, real estate, and politics, culminating in the Presidential election of 1960, when Sam Giancana got the Chicago vote out for Kennedy’s son John, in exchange for what he assumed would be reduced Federal pressure on the mob. Considering Illinois was one of the last states to declare in an extremely tight race, this could be construed, and certainly was by Giancana, as throwing Kennedy the election.

While John F. Kennedy was establishing that an Irish-Catholic could become President, a series of highly insular, and incredibly violent, gang wars was beginning in Boston. Filling the vacuum left by one of its casualties, James “Whitey” Bulger consolidated power in the disparate, clannish Boston underworld. A native of the working-class, Irish-American Southie neighborhood, Bulger courted the image of man of the people but held on to power with extreme brutality, not being above dispatching enemies with his bare hands. Bulger’s position, maintained for over twenty years, was buttressed through his position as a criminal informant for the FBI, receiving protection and information from Agent John Connolly. Perhaps even more vital to Bulger’s long reign was his younger brother William, a local political power broker, who served in the House of Representatives as well as the state Senate. It is doubtful that William aided, or even knew the extent of, his brother’s criminal activities, but his status leant authority to Whitey’s image.

Whitey Bulger represents a shifting point in the figure of the Irish-American mobster/politician/businessman. Though politically protected, he was not a politician and he certainly did not try to move through the world of high-finance and or seek respectability. By Bulger’s heyday, the Irish mob had wasted away to a fraction of its former self. If JFK’s election had made Irish-Americans definitively mainstream, it also allowed them to take part in the White Flight in the ‘60s and ‘70s, leaving the ghettos and insular neighborhoods of major metropolitan cities for the suburbs. Boston and Hell’s Kitchen in New York City were two of the last homes of the good old-fashioned Irish-American stick-up man, and, by 1994 when Bulger fled an encroaching net of Federal agencies, even their time was over.

Just under two years before the eventual arrest of Bulger in June of 2011, Joseph Kennedy’s youngest child, Edward, died of brain cancer after a long and respectable career in the Senate. Though his personal character was certainly not untarnished, Edward Kennedy was never considered a crook. The contrast is apparent: Edward Kennedy was a politician and Whitey Bulger was a mobster. By the opening years of the 21st Century the category of Irish-American mobster/politician/businessman had disintegrated into disparate parts.

The character of Nucky Thompson might mirror elements of John Morrissey, Joseph Kennedy Sr., and Whitey Bulger, but the style of his reign is based on Enoch Johnson, who ran Atlantic City for much of the early 20th Century. There are many divergent points between Johnson and Thompson, such as Johnson’s massive frame vs. Thompson’s unassuming, slight stature or Thompson’s early remarriage, but the most startling is that of ancestry and upbringing. The latter is easier to delineate. Enoch Johnson’s father was Smith Johnson, county sheriff, who helped run the rackets for Louis Kuehnle (the basis for the character of the Commodore) and would later help set up his son in politics. Enoch Thompson grew up in a poor Irish-American household and rose under his own power.

The point of ancestry is more difficult to deal with. I’ve been able to find no evidence from any credible source that Johnson was Irish-American. ‘Johnson’ is a common enough Irish name, but it is also a common English and Scottish one. (‘Thompson’, itself, is not an extraordinarily Irish-Catholic name, as a visiting Sinn Fèin representative remarks.) Whether or not Johnson had Irish blood becomes less important when it becomes apparent that he did not style himself as Irish-American and that his machine did not have a predominately Irish-American base.

Of course, as Jacob Silverman has said, Boardwalk is “a multicultural parade”, incorporating Italian and African-American, WASP, and Jewish players. All collaborate, betray, and murder each other regardless of background, seeing themselves as, primarily, Americans. However, as much as Nucky Thompson might consider himself to be an American businessman and politician, he is also, inescapably, an Irish-American mobster. His execution of James Darmody in the final episode of the second season, pulling the trigger himself for the first time in his life, cements this. Meanwhile, Thompson has set himself up as father and husband, leaving the Ritz and keeping a respectable family home; inversely, his relationship with his wife Margaret has lost the openness the series flirted with allowing them for so long. And so Thompson stands, at the end of the second season and for the first half of the third, skirting stereotype: the vicious mobster who hides his increasingly dark deeds from his family and the general public.

In 1929, Enoch Johnson hosted a conference of Italian-American and Jewish mobsters in Atlantic City. The purpose of this conference was lay out plans for the future of what would become known as The Syndicate or The Outfit, a national conglomeration of mobsters patterned after a corporation. No Irish-American mobsters of any importance, such as Daniel Walsh, George Moran, or William Dwyer, were invited. It has been alleged by certain historians that one of the purposes of the conference was to push the Irish out, and, indeed, the following years would see a surge in Italian-American and Jewish control of mob activities.

Whether or not Thompson will survive a further six years to see the Atlantic City conference of 1929 is difficult to say, considering Boardwalk’s high body count and willingness to make some of the bodies those of central characters. However, if the second season was devoted to showing how Thompson dealt with those who personally despised him, those who felt unjustly treated by him, and those who didn’t consider him sufficiently brutal, Thompson will now have to deal with the fact that the days of the Irish American mobster/politician/businessman are quickly waning. Enoch Johnson ran his Atlantic City until 1941, when he was put away for tax evasion for four years. He died in 1968, in bed. It is doubtful this will be Enoch Thompson’s fate.