Lake Oahe, near the town of Cannon Ball, ND, 2016. Photograph by Rebecca Bengal.

Lake Oahe bears little resemblance to the common conceptions of a lake—the round basins formed by volcanoes, the crescent shapes of fluvial lakes, the appendage-like body of Lake Erie, whose name comes from the Iroquois language and means “long tail.” In its narrow stretches, Oahe appears as slender as one of the Finger Lakes of New York, and yet it ends in no pointed shore but an artificial obstruction.

Today it is the ninth-largest lake in the country, spanning a little over 230 miles, stretching from Pierre, South Dakota, and traveling nearly as far north as Bismarck, North Dakota. It is only fifty-six-years old. Oahe is a Lakota word, translating in English to “foundation,” or something to stand on.

Seen in person in its forks and bends, Oahe looks more like a river, wide and calm. For twelve thousand years, it was part of the Missouri, the second longest river in the world. “I think God wished to teach the beauty of a virile soul fighting its way toward peace—and his precept was the Missouri,” wrote John G. Neihardt in The River and I, the chronicle of the fifty-six-day canoe trip he took along the river in 1909, twenty-two years before he would record the life story of the holy man Black Elk in Black Elk Speaks. “But the Missouri—my brother—is the eternal Fighting Man! The Missouri is more than a sentiment—even more than an epic.”

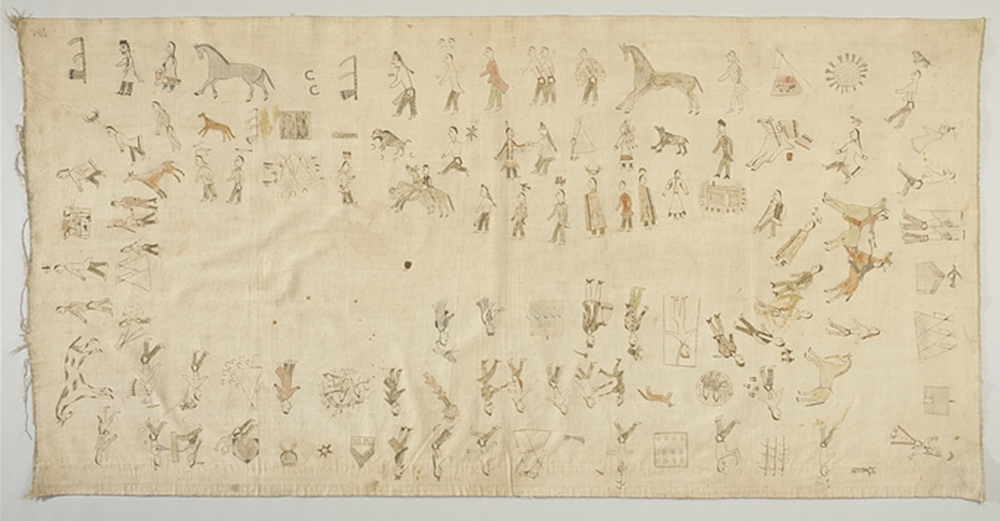

The Seven Council Tribes of the Sioux Nation depended on the Missouri, traveling and making camp along its shores; following bison herds; chronicling their nomadic journeys, hunts, battles, medicine-making, and blizzards in the Lakota winter counts, the annual pictographic records drawn on muslin and buffalo hide. In the Lakota Lone Dog winter count of 1825–26, the Missouri floods are illustrated by a row of half-circle symbols cresting a horizontal line—waves, maybe, or heads above water. In 1833 seven separate winter counts, among those in the Smithsonian Institution’s collection and featured in the book The Year the Stars Fell, record a meteor shower on November 12 over the Missouri and the Dakotas in illustrations of constellations spilling from the sky.

The winter counts also allude to the 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie—which pushed the Sioux Nation into territories on the western side of the Mississippi—the gold rush in the sacred Black Hills, and the death of Crazy Horse. On the solar eclipse of August 7, 1869, a thousand-mile stretch of the Missouri (including what later became Lake Oahe) was in the path of totality, also documented in the counts. The cabin of Sitting Bull, where he was surrounded and killed by police in 1890, is depicted in the 1890–91 winter count. Two alleged burial sites of the great Sioux leader rest on the shores of the Missouri—one in Mobridge, one in Fort Yates, each claiming to be the actual grave, and both in the path of the floods less than a century later that would create Lake Oahe from the drowning of past civilizations.

On August 17, 1962, President John F. Kennedy Jr. traveled to Pierre to dedicate the Oahe Dam, completed by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. “Water is our most precious asset, and its potential uses are so many and so vital that they are frequently in conflict,” Kennedy told the gathered crowds. Kennedy said the Oahe Dam would produce enough electricity “to light the entire city of Edinburgh, Scotland” and to irrigate Luxembourg.

When we are inclined to take these wonders for granted, let us remember that only a generation or two ago all the great rivers of America, the Missouri, the Columbia, the Mississippi, the Tennessee, ran to the sea unharnessed and unchecked. Their power potential was wasted. Their economic benefits were sparse. And their flooding caused an appalling destruction of life and of property.

The project was conceived shortly after D-Day and undertaken in earnest beginning in 1944, when it was met with protest by the tribes who lived on its banks and understood that the lake would ecologically transform the area, wiping out their homes, their farmland, their means of survival. One of the bands of the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe is the Minnicoujou, whose name means “planters by the water.” In the early 1960s, as the dam neared completion, more than 160,000 acres of the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation and 300,000 acres of the Cheyenne River Reservation were submerged by floods resulting from its construction. “The Oahe Dam destroyed more Indian land than any other public works project in America,” writes Michael L. Lawson in Dammed Indians: The Pick-Sloan Plan and the Missouri River Sioux, 1944–1980. People who grew up pre-Oahe remember life in the valley and its relatively gentle breezes, before members of the tribes were forced to move to higher, harsher ground and a new way of life, disconnected from the valley they had depended on economically, culturally, and spiritually.

Gone were the “wooded, riparian bottomlands, with fertile soils, abundant water supplies, timber, wildlife habitat, rare plants used for medicinal purposes,” according to a 2013 Standing Rock Sioux resolution calling for an oversight hearing on the impact of Oahe Dam on the water, land, and forced relocation of the tribes of the Missouri River Basin. The dam was one of six built between 1946 and 1966 under the auspices of the Pick-Sloan Plan. Named for two officers of the Army Corps of Engineers, Pick-Sloan was conceived in 1943 in response to severe floods that year. Its numerous goals included flood control and increasing municipal water supply, as well as producing hydroelectric power and enhancing recreational opportunities.

The Standing Rock Sioux scholar and writer Vine Deloria Jr. called Pick-Sloan “the single most destructive act ever perpetuated on any tribe by the United States.” “Whole forests vanished,” LaDonna Brave Bull Allard, who was then the tribal historian of the Standing Rock Sioux, told MSNBC reporters in September 2015. Seven months later, she would open her family’s land to the first camp set up by the indigenous-led movement to stop the Dakota Access Pipeline, a $3.8 billion, 1,172-mile-long pipeline transporting crude oil and crossing under Lake Oahe, the primary source of drinking water for the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe. From April 2016 until late February 2017, thousands of Native Americans and allies built and sustained a nonviolent occupied resistance centered at the confluence of the Cannonball River and Lake Oahe, on the northern border of the reservation. Oahe was always part of the narrative. “This is not something a long time ago,” Allard told Democracy Now! in a September 2016 interview, as members of Dakota Access Pipeline security were filmed unleashing security dogs on Native Americans seeking to protect a burial site from the company’s bulldozers. “This is me who lived through this. And so they came, and they flooded it...If you talk to the people that are my age and older, you can hear the grief in our voice, because we still grieve for the loss of this land. And they moved us on top of the hills, where it is more of a clay-based soil, so we could no longer grow gardens, we could no longer plant trees, we could no longer do the things we did.”

What does Lake Oahe hold? It holds the lands of the Lakota people, and of the earlier Arikara people, who lived in earth lodges along the river. It is adjacent to the purported grave of Sacajawea, the Shoshone woman who accompanied Lewis and Clark on their Missouri expedition. As late as 2015, teams of volunteers reported that they were still reburying human remains that had washed up on Oahe’s shores from flooded burial grounds.

It holds the entire submerged town of Forest City, a former agricultural community and fur-trading post on the eastern shore of the Missouri. A bridge over the river still bears its name, but by the time Oahe Dam was completed, Forest City’s boom had ended; one local newspaper, recounting the event in 2001, ran the headline “The Coming of Oahe Whispered Death to Forest City…” Archives at the Dakota Sunset Museum in nearby Gettysburg, where a few Forest City residents relocated after the damming, contain chronicles of the town’s colorful history. A collections assistant read aloud to me newspaper accounts of a 1901 shootout of a local cowboy, straight out of a movie Western: “Rome Glover killed Abner Daly from an upstairs window of a saloon.” Daly was buried in the town’s cemetery, now seventy feet underwater; according to the Potter County News, it’s “a place made famous by being peopled with a number of persons who died unnatural deaths.” None of those were reinterred.

It holds fifty-one recreation areas, visited by 1.5 million visitors per year. It holds a maximum depth of 205 feet. It holds walleye, smallmouth bass, northern pike, channel catfish, Chinook salmon, and the pallid sturgeon, a ray-finned fish that tends to live to be at least fifty and sometimes as old as a hundred. Prior to the damming of the Missouri, the pallid sturgeon migrated far upstream every few years to spawn. Post-Oahe, it has become an endangered species.

As the Oahe dam neared completion in the early 1960s, one of the last persons left standing on its bluffs was walked out at gunpoint, according to locals. Red Tomahawk “stood on the hill and sang his death song,” former Standing Rock Sioux Tribe councilwoman Phyllis Young remembered in 2015. “He prepared for death because he had nothing left. We had nothing.” Young was ten years old when she watched her own family’s home flood, their chokecherry trees drowning in the new lake. Frank Duchenaux was the chairman of the tribe in that time, nicknamed “the Little Defender” for engaging in years of negotiations with the Army Corps of Engineers and others in Washington, DC. His own home was sunk below Oahe; his daughter Candace Ducheneaux keeps a photograph of her father and brother watching from safe ground as the floodwaters rose. “Years later,” writes Lawson in Dammed, “a visitor to Cheyenne River [reservation] wondered why there were so few elders on the reservation. Residents explained that ‘the old people had died of heartache’ after losing their homes.”

What does a lake hold? It holds the river that was the destination for Black Elk’s spirit journey back to the place where he had his first mystic vision as a child. As an adult, abroad for two years, Black Elk was homesick and wearing “Wasichu clothes” (Wasichu has many spellings and connotations in Lakota; “white man” is one of them) as part of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West touring show. He sat down to breakfast one morning in Paris, fell out of a chair, and, he told Neihardt, floated away on a cloud to which he clung fast. Slowly he began to recognize the country that materialized below. “I saw the Missouri River,” he would recall. “Then I saw far off the Black Hills and the center of the world where the spirits had taken me in my great vision.”

“Did you ever hear music that made you see purple?” Neihardt wrote in The River and I as he canoed the Missouri. He was referring to the sound of Eagle Rapids, but he could just as easily have been speaking of the whirlpools that once swirled at the place where the Missouri meets the Cannonball. “The river takes its name from those stones which resemble cannon balls,” wrote Lewis and Clark in their 1804 journals. After the damming of the Missouri, the current turned placid and the round stones that polished those waters became memories too. The camp founded on La Donna Brave Bull Allard’s land was given the name Sacred Stone in homage. One of the largest of the sacred stones is on display outside the Standing Rock town of Cannon Ball—a historical marker in a gas station parking lot.

What else does a lake hold? It holds the Dakota Access Pipeline, which has been operational since June 2017. Despite the fact that it is still under environmental review, the DAPL transports 500,000 barrels of crude oil daily. The indigenous-led resistance against the pipeline was a spiritual one, guided by the Lakota principle Mni Wiconi: water is life. Every morning, before the last of the water protectors was led out of Oceti Sakowin camp by armed officers on February 23, 2017, women and others held a ceremony on the shores of the Cannonball River near its confluence with Oahe, offering prayers for the water. The lake holds those too.

Read more on Water in the Summer 2018 issue of Lapham’s Quarterly.