Fireworks on the Night of the Fourth of July, by Winslow Homer, 1868. Minneapolis Institute of Art, Gift of Dr. and Mrs. Robert D. Semsch.

On July 4, 1826, Americans woke before dawn. Some squeezed into blue coats that had been folded in trunks for decades and covered what was left of their hair with tricornered hats, long out of fashion. At sunrise, cannons boomed, church bells pealed, and across the nation’s scattered villages and modest cities, aged “heroes of ’76” fired salutes from flintlock muskets, marching down dirt thoroughfares to drum and fife and the cheers of the crowd. Most parades then proceeded to a grove or a town square for a reading of the Declaration of Independence, followed by high-flown speeches honoring this momentous day: the semicentennial, or “Jubilee,” as they called it. Some addresses spun wild visions in which the twenty-four states dotted with family farms and the vast forested territories beyond would one day become a powerful empire. The listeners adjourned to eat barbecue and then headed to the taverns for rounds of toasts—to George Washington, to the flag, to the eagle, to the first half century of American life.

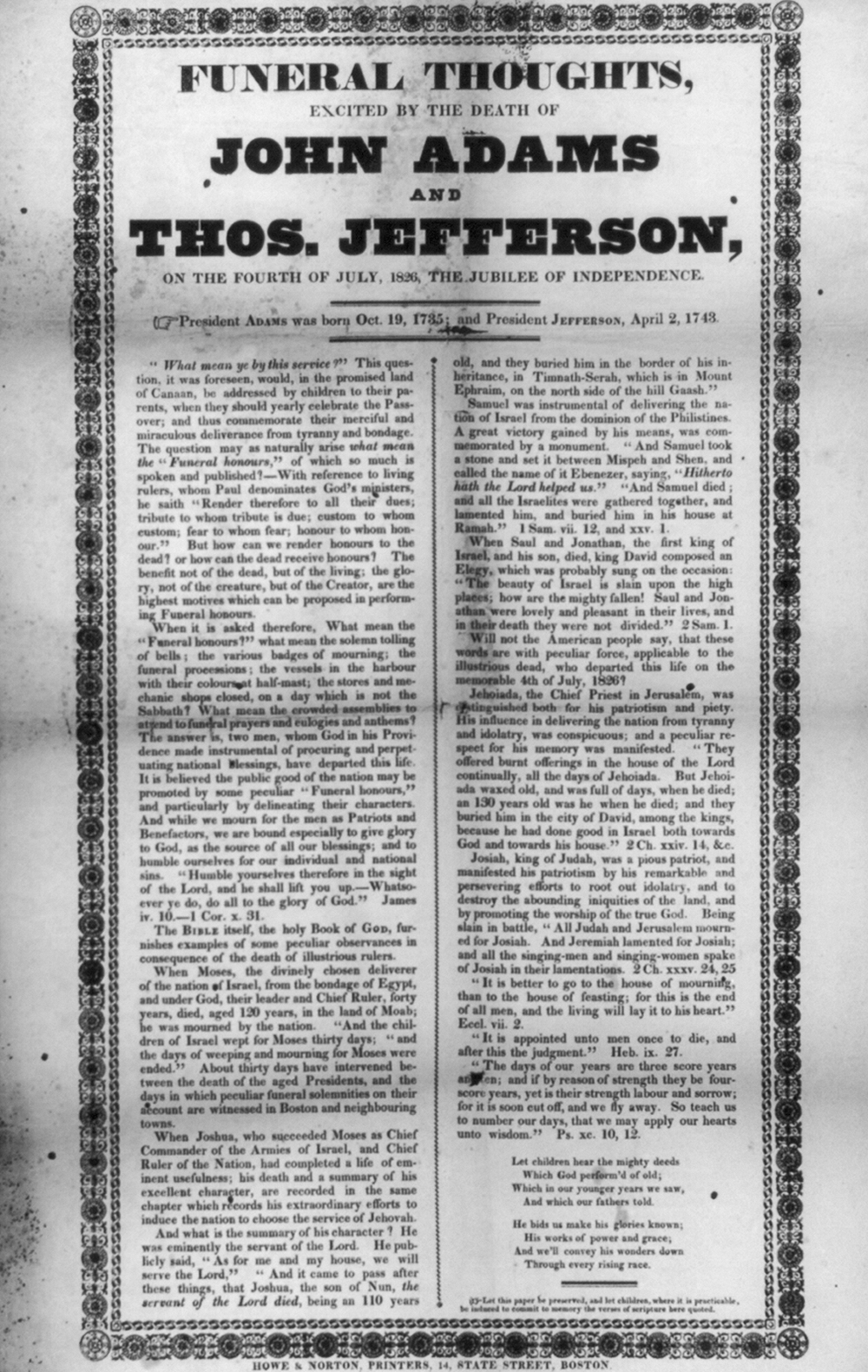

As orators waxed poetic on “the imperishable names of the founders” who had risked execution as traitors to the Crown in order to bequeath the everlasting legacy of freedom, Thomas Jefferson died in his bed in Virginia. Hours later, sitting in a chair at home in Massachusetts, John Adams followed him. It was exactly fifty years after the Declaration they had drafted together was approved, founding the United States of America. Many regarded this strange historical coincidence as a divine message, God’s seal of approval on the American Revolution and a promise of perpetuity for its outcomes. Unmistakably, it was the threshold of a new era, the end of the beginning. The young nation had outlived the men who made it. What was next?

One man in Indiana claimed to know. Robert Owen was a rich industrialist, renowned in this country and in Europe for running philanthropic experiments in a cotton mill he owned in New Lanark, Scotland. As the nation celebrated its Jubilee, he mounted the stage at New Harmony Hall, a former church that he had purchased, along with the twenty thousand acres surrounding it. Intrigued by communal groups like the Shakers and emboldened by his experience applying his social theories to the factory workers he employed, Owen had sailed for the United States to propose a project on a far grander scale. His fame had spread after he addressed the assembled leaders of the federal government the previous year in Washington, DC, pitching a wholesale reorganization of American life that was surprisingly well received. It was pouring rain on the Wabash River that Fourth of July, but a thousand people packed the building, traveling to this rural outpost from all over the country to hear what this slight Welsh gentleman had to say.

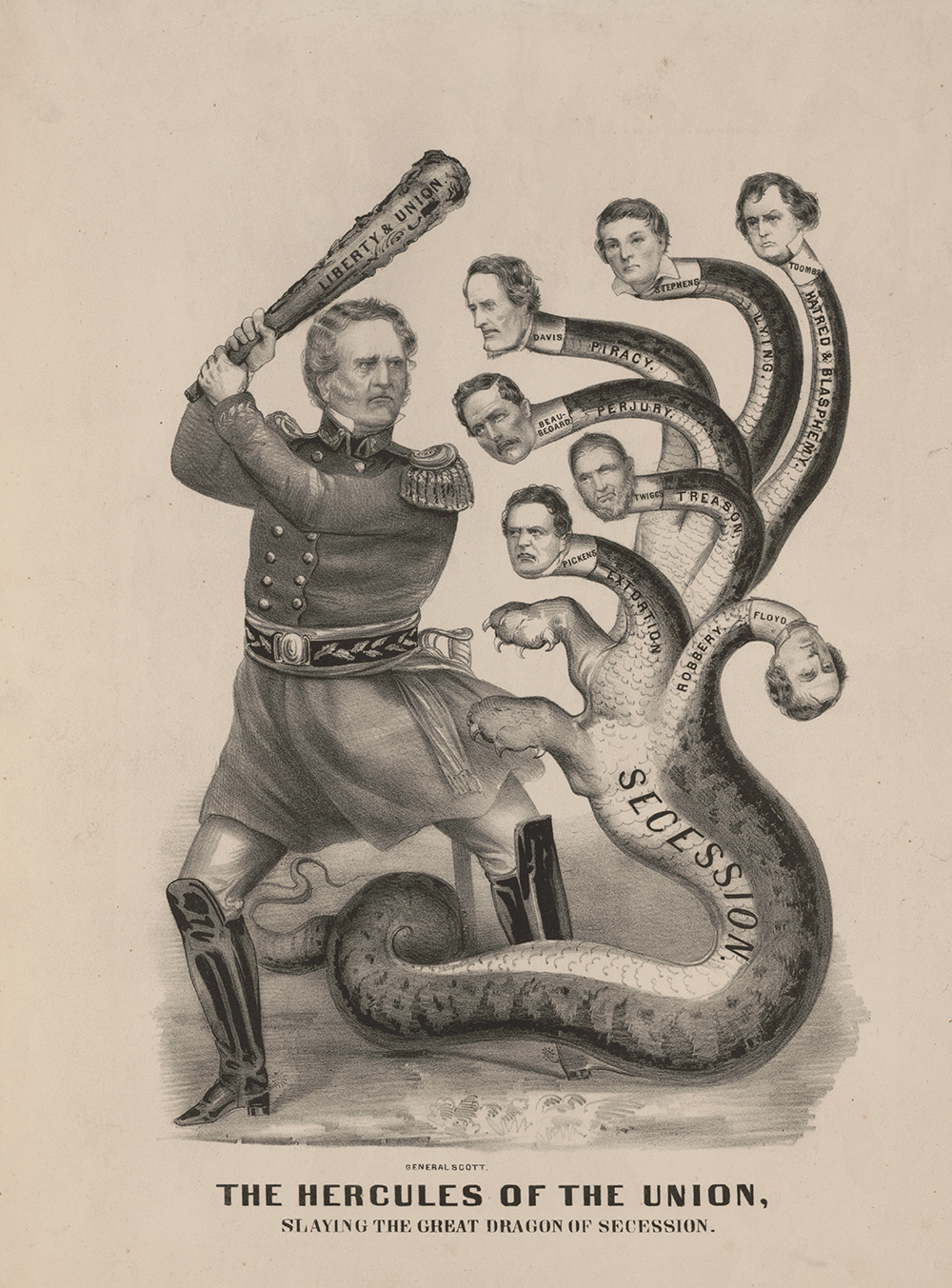

While orators in other cities and towns sang the praises of the American founders, Owen focused instead on the limits of their achievement. They had been forced to settle for mere “political independence,” he claimed, hemmed in by the old-world prejudices that still dominated their era. But they could glimpse “a stronger and clearer light at the distance,” he explained, and the founders trusted that their descendants would pick up where they left off, completing the transformation they had only begun. Indeed, a second revolution was required, a new battle for freedom “superior in benefit and importance to the first revolution.” He asked the crowd, “Are you prepared to imitate the example of your ancestors? Are you willing to run the risks they encountered? Are you ready, like them, to meet the prejudices of past times, and determined to overcome them at all hazards, for the benefit of your country and for the emancipation of the human race?” To launch this revolution, Owen presented his Declaration of Mental Independence to supplant the founding document adopted fifty years before that day. Its object was to slay a “Hydra of Evils” enslaving mankind the world over: specifically, the “threefold horrid monster” of private property, religion, and marriage.

From our vantage point, almost two hundred years later, Owen’s social revolution seems destined to fail, his interpretation of the founders as heralds of secular communism laughable at best. Capitalism, evangelical Protestantism, and the nuclear family would ultimately win the day, becoming far more deeply entrenched in American culture during Owen’s lifetime. But from where he stood, the future of the United States was wide open, rolling out like a screen on which marvelous utopian visions could be projected.

European visitors like Owen were astounded by the simple, direct dealings of the people carrying out the experiment that was early America: their free and easy manners, the “extreme equality” across classes, and their universal, near-fanatical engagement in politics as a form of social engineering. They seized every local election or civic debate as a new opportunity to invent the country of the future. Railroads and the telegraph would soon join steamships and canals in the network of new technology connecting the expanding country for trade, the exchange of ideas, the development of new towns, new states, new industries. This restless mobility and ambition turned away from the past, pushing further into the vast and magnificent West. The booming agriculture of the South fed the beginning of the Industrial Revolution in the North, where new systems of integrated manufacturing processed these abundant raw materials for global commerce, auguring the great wealth that would one day drive a great nation.

Viewed in another light, of course, this scene was not so utopian. The workers in these new factories might labor sixteen hours a day, six days a week. Married women were relegated to the status of dependent children, unable to control property, vote, attend college, or sue in a court of law. The land, of course, was far from vacant; it was inhabited by long-established nations battling against extermination at the hands of white settlers. And the economic dynamo driving the young nation to prominence on the world stage was the forced labor of a million and a half people of African descent enslaved in this land of radical freedom, a number that would more than double in the coming decades. The conditions under which they lived were unspeakably brutal, and American law unambiguously doomed their children and their children’s children to the same outrages.

Owen was right: a Hydra of Evils threatened the most profound ideals of the American project, and the recently departed founding generation would not be the ones to slay it. As his overflow audience suggests, many were ready to take up the mantle of a social revolution to right the many wrongs created or left unaddressed by the political revolution of their grandfathers. In the next half a century, hundreds of thousands of Americans pledged themselves to a vision of the nation based on collectivity, equality, and freedom. Before Owen arrived with his plan to make America more radically free, African American activists across the North were organizing to protest slavery and racial inequality, establishing community institutions to support those whose very lives were a form of resistance. As their struggle mounted in the 1820s for emancipation and citizenship, the first major wave of socialism and workingmen’s organizations raised their voices in protest, further revealing American social equality to be a myth. Around 1830, a radical turn in antislavery activism led to the first national social movement to bring together Americans across race, class, and gender, aiming not only to free enslaved people but to rout out tyranny wherever it remained.

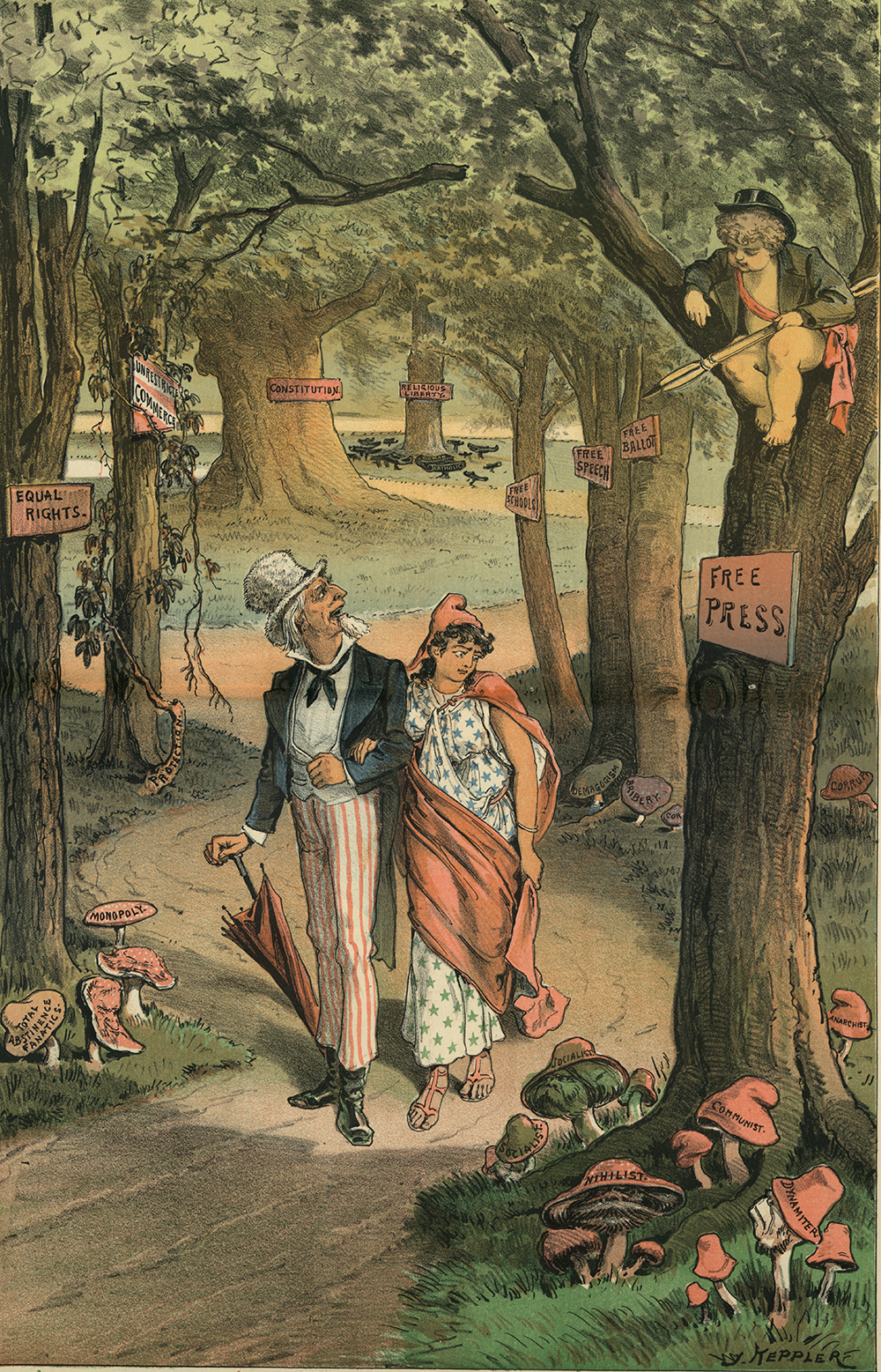

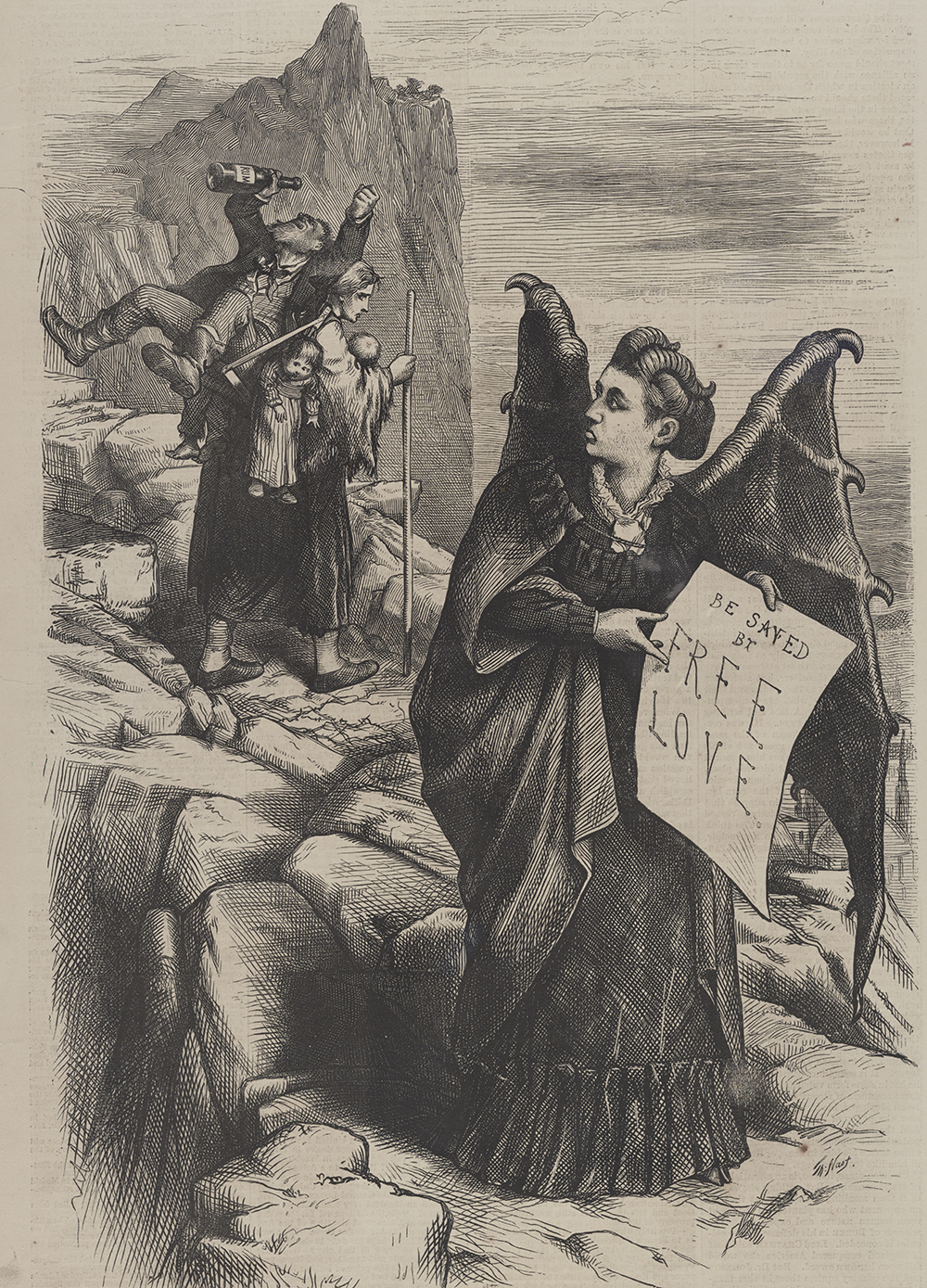

This intensifying culture of dissent met a violent backlash from the American mainstream. But even as protesters were mobbed, assaulted, and prosecuted, their printing presses smashed, their lecture halls burned to the ground, even as they were murdered, the field of activism expanded. The country’s first philosophical movement called for the end of all external authority and inherited institutions at this time, feeding an increasing embrace of civil disobedience. Many came out of the churches, leading some to “come out from the world” as a new wave of utopian socialism flowered in communes and a growing labor movement. From the beginning, this tradition of protest took aim at private life just as much as traditional politics; marriage was a lightning-rod issue for socialists, women’s rights activists, and Free Lovers who would liberate women from the bonds of maternity and domestic servitude. But in the midst of debates about the abolition of “wage slavery” and “marriage slavery,” westward expansion triggered a national crisis over the fate of millions literally held captive.

As the founding compromise between the North and the South wore thin, antislavery activism took a militant turn around 1850. White activists began calling for the end of the Union. Black activists renewed their deliberations about a walkout on a national scale, abandoning the United States in search of a more promising land. Blood spilled on city streets, across the prairie, and in the halls of Congress. Genteel reformers embraced violence and treason, speeding a civil war waged not against slavery but against abolitionists. After four years of bloody internecine warfare, activists celebrated the victory of emancipation and an unprecedented opportunity to right the wrongs of the country’s first revolution. With Reconstruction, ideas that had once seemed fringe were now squarely on the national agenda. But as former fanatics turned to politics, they found their values and their movements tested. By the time the nation rang in its one hundredth anniversary in 1876, patriotic fervor could not mask its tailspin into lawless violence. In the following year, the federal government would permit a white supremacist counterrevolution in the South but crack down brutally on aggrieved workers across the North, watershed reinforcements of inequality that threatened to undo the advances of the preceding half century.

Robert Owen’s choice of the Fourth of July to launch his attack on American society, and his revision of the nation’s founding document into a radical manifesto, were common tactics among the agitators of his century. While most Americans saw the Fourth as a day of celebration, activists remembered that it commemorated a protest and kept up that tradition by forcing the nation to reckon with its own ostensible values. Native Americans, industrial workers, women’s rights advocates, Free Lovers, insurgent militias, and many others seized the symbolic richness of Independence Day and the language of the Declaration to raise their own calls for freedom and equality. After all, that initial manifesto was a reminder that the United States of America had only recently been no more than an idea for a radical utopian community—a set of principles and practices that a group of men made up together. Perhaps it could be done again, but better.

Thus, even as they aimed to “disorganize” society at its roots, these radicals saw themselves as the true inheritors of the American project who would keep its ideals alive. Nineteenth-century radicals’ battle for social justice, freedom, and equality was defined by their struggle with the nation and its meaning: They refused to vote, demanded to vote, served in the government, and plotted armed coups to overthrow it. They burned the Constitution, hung the flag upside down, and yet returned to the specific form and language of the founding documents again and again to articulate the new versions of America they hoped to bring about. They spearheaded schemes to leave the country en masse, then signed up for military service, ready to die for it. In relation to the founders, they heeded both Owen’s injunction to “imitate the example of your ancestors” and the abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison’s call to “blush for their self-evident injustice, to shun the evil example they set.” They revered Thomas Paine but denounced George Washington as a “man stealer.” Even those whose solutions involved abandoning the United States altogether, aligning with international networks and denouncing the violent chauvinism of national identity, often declared that they acted in the “spirit of ’76.” Despite its galling and destructive hypocrisy, the nation never seemed to exhaust itself as a source of radical promise.

From the book American Radicals: How Nineteenth-Century Protest Shaped the Nation by Holly Jackson. Copyright © 2019 by Holly Jackson. Published by Crown, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.