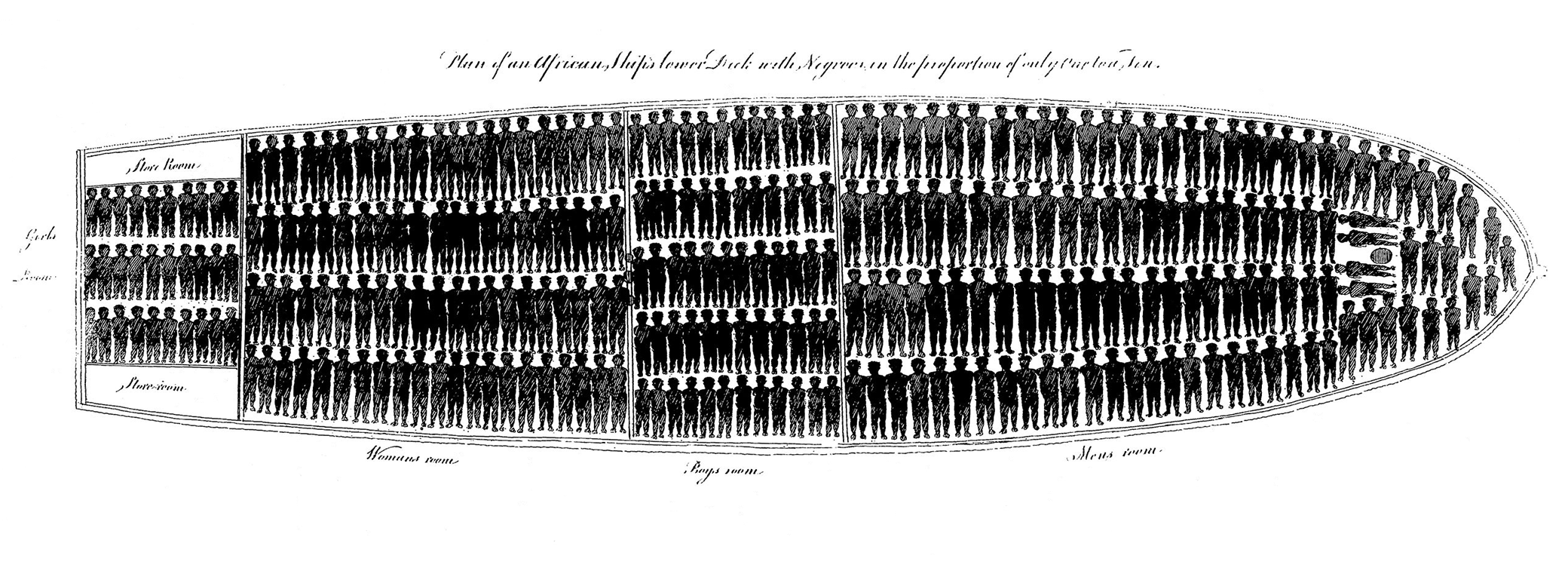

Plan of an African Ship’s Lower Deck with Negroes in the Proportion of Only One to One Ton, by Sir William Elford, c. 1789. Library of the Society of Friends.

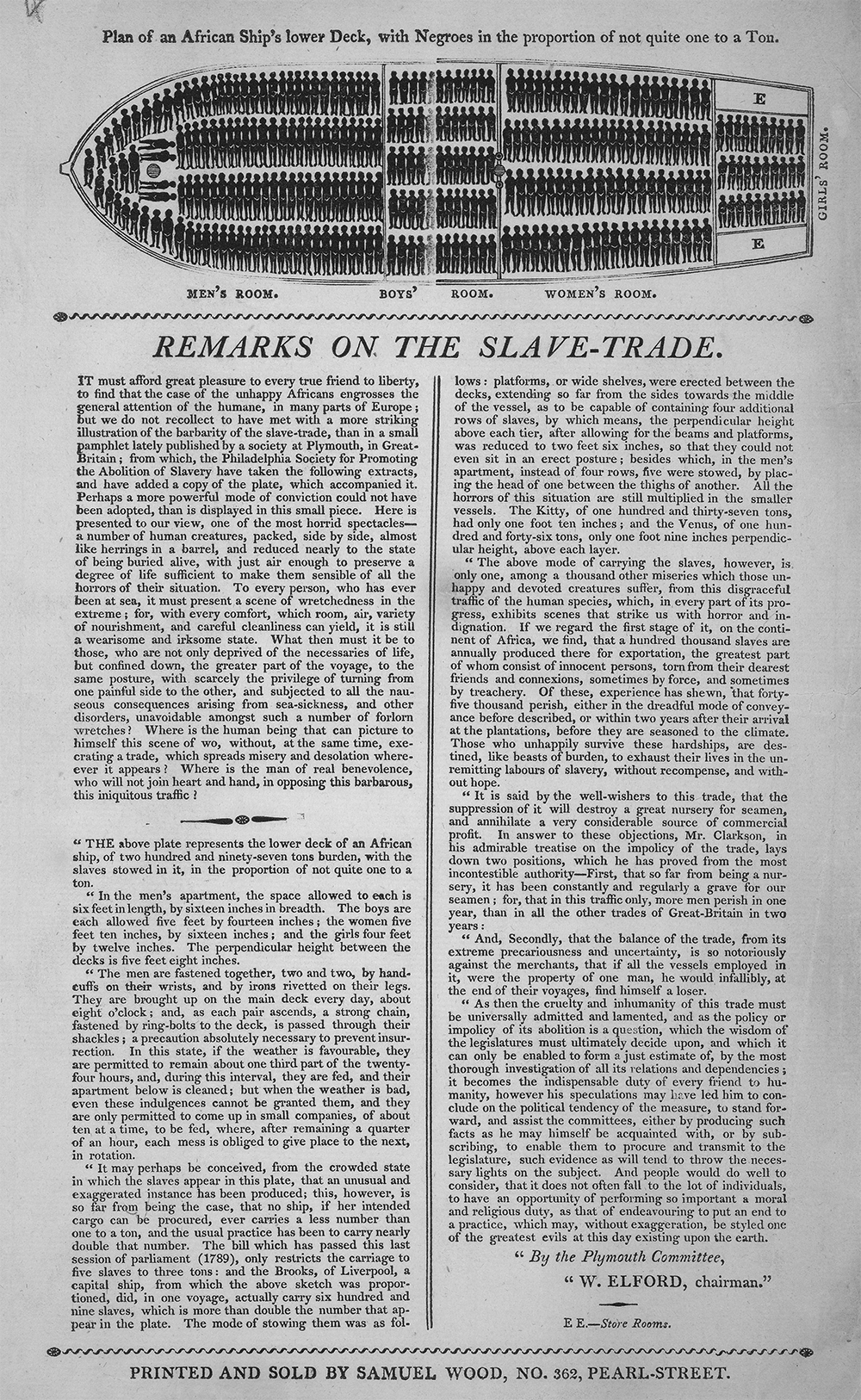

The first abolitionist engraving of a slave ship, titled Plan of an African Ship’s Lower Deck with Negroes in the Proportion of Only One to a Ton (1788), was conceived by the Plymouth Committee of the Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade in England. Viewed from above this schematic plan shows a cargo hold packed with hundreds of enslaved Africans—represented by tiny, uniform, darkly shaded figures—and so hints at the barbarity they were made to suffer during the Middle Passage, the transatlantic voyage from Africa to the New World slave markets. Among the first to publicly acknowledge the visual impact of this image, printed on paper 6¾ by 16 inches, was African-born Olaudah Equiano, whose letter to the Plymouth Committee appeared in a London newspaper, the Public Advertiser, on February 14, 1789. In his own carefully chosen words, Equiano professed:

Having seen a plate representing the form in which Negroes are stowed on board the Guinea ships, which you are pleased to send to the Rev. Mr. Clarkson, a worthy friend of mine, I was filled with love and gratitude towards you for your humane interference on behalf of my oppressed countrymen.

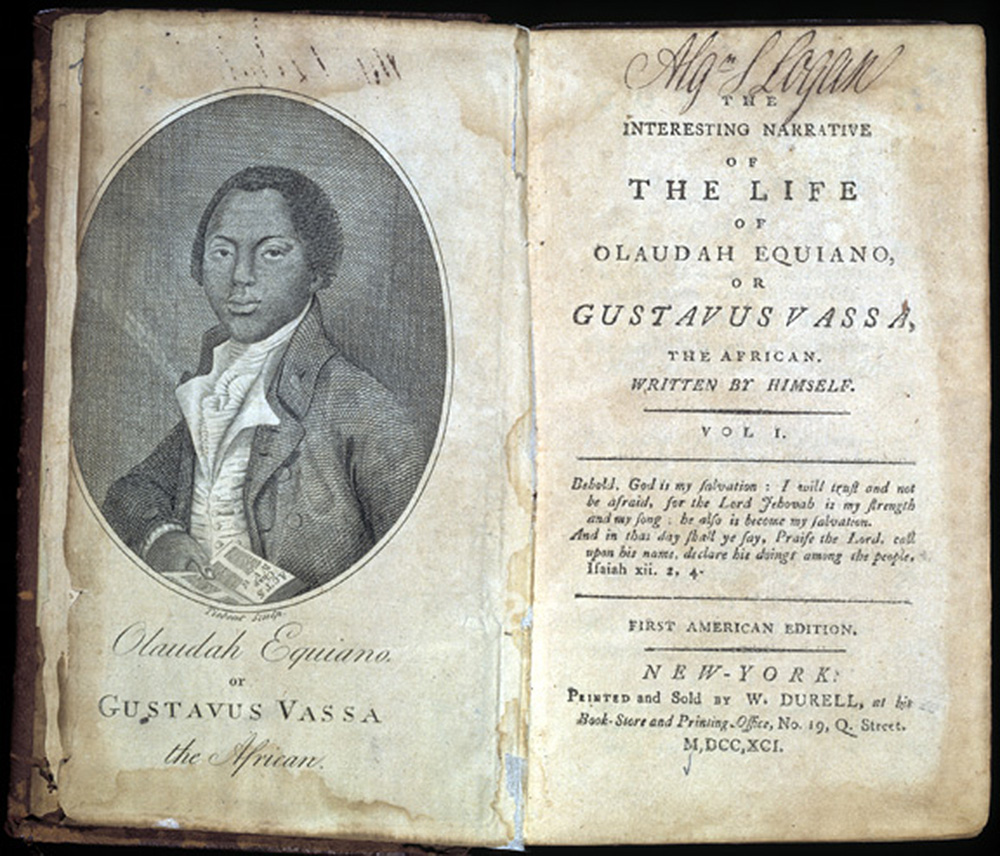

An ex-slave and free man of color living in London, Equiano was an outspoken opponent of the slave trade, who regularly described his personal experience of slavery at public gatherings. His public performances had gained Equiano such a reputation that by the time his letter appeared in the Public Advertiser, he was on the verge of publishing his enormously successful autobiography, The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano or Gustavus Vassa, The African, in March 1789.

It is not hard to imagine why Equiano immediately recognized the print’s capacity to serve the goals of abolition. For him, it provided a shocking visual reminder of a place and an experience that he himself had known. Yet still it must have been difficult for him to conceive of how anyone could render such an image. Indeed, one wonders just exactly what he felt, what he remembered when Thomas Clarkson showed him the oblong engraving of the plan of the slave ship.

As rudimentary as it was in its initial rendering, Equiano nevertheless was transfixed by its power, perhaps even in a state of utter disbelief at its ability to represent such a site of terror and violence. In that moment of recognition, the wound from the initial trauma of being torn away from the land and people he knew and forcibly taken to some unknown people and place was slashed anew. One can picture how his eyes might have followed the contours of the darkly shaded figures, counting each one, possibly imagining the face of someone he once knew. Fine black lines representing the walls that divided groups of figures by age and sex might have caused him to pause and think about which space he had occupied or the people who had lived and died next to him. The combination of rows and rows of black figures separated and surrounded by fine black lines schematically mapped the space of the hold, marking a route to untold horror. The labels “boy’s room,” “girl’s room,” “men’s room,” “women’s room” appeared as signposts indicating the contents stored within.

The title above the bullet-shaped schematic, plan of an african ship’s lower deck with negroes stowed in the proportion of only one to a ton, bluntly and succinctly described the purpose of the drawing while revealing a modern system of calculation, commerce, brutality, and human domination. So haunting in its graphic depiction, the plan of the slave ship must have seemed capable of psychically transporting Equiano back to that foundational moment in the swollen belly of the slave ship when he was born into an African diaspora. As he described in his autobiography:

The closeness of the place, and the heat of the climate added to the number in the ship, which was so crowded that each had scarcely room to turn himself, almost suffocated us. This produced copious perspirations, so that the air soon became unfit for respiration, from a variety of loathsome smells, and brought on a sickness among the slaves, of which many died, thus falling victims to the improvident avarice, as I may call it, of their purchasers. This wretched situation was again aggravated by the galling of the chains, now become insupportable; and the filth of the necessary tubs, into which the children often fell, and were almost suffocated. The shrieks of the women, and the groans of the dying rendered the whole a scene of horror almost inconceivable.

This scene in which Equiano recounts his chilling memory of psychological terror and physical captivity in the hold of a slave ship is one of the defining moments of his narrative and a passage that since has been recited frequently as an eyewitness account of the Middle Passage.

As an eyewitness and a survivor then, Equiano was in a unique position to endorse the plan of the slave ship, the first graphic representation to provide a visual complement to his own unforgettable hell. By lending public support to this image, his letter situated it within a discourse of artistic production, political action, and popular representations of the black body. The fact that Equiano recognized the hundreds of roughly drawn, nude black figures lying neatly in the coffin-shaped hold as his “oppressed countrymen” breathed life into their corpse-like representations. Indeed, by calling them his “oppressed countrymen,” Equiano immediately brought the issue of their humanity to the attention of his readers.

This first engraving of a crowded slave ship interior was not an isolated print. Rather, it served as the illustration for a small, square, four-page pamphlet printed by the Plymouth Committee. Not only was Equiano profoundly affected by the image, he was deeply moved by the explanatory text of the abolitionist tract as well. The cataclysmic text of the pamphlet reads:

[1] The annexed Plate represents the lower deck of an African Ship of 297 tons burthen, with the Slaves stowed on it, in the proportion of not quite one to a ton.

[2] In the Men’s apartment, the space allowed to each is six feet in length, by sixteen inches in breadth.—The boys are each allowed five feet by fourteen inches.—The Women, five feet ten inches, by sixteen inches; and the Girls, four feet by one foot each.—The perpendicular height between the Decks is five feet eight inches.

[3] The Men are fastened together, two and two, by hand cuffs on their wrists and by irons rivetted on their legs.—They are brought up on the main deck every day, about eight o’clock, and as each pair ascend, a strong chain is fastened by ring bolts to the deck, is passed through their Shackles; a precaution absolutely necessary to prevent Insurrections.—In this state, if the weather is favourable, they are permitted to remain about one-third part of the twenty-four hours, and during this interval they are fed, and their apartment below is cleaned; but when the weather is bad, even these indulgences cannot be granted them, and they are only permitted to come up in small companies, of about ten at a time, to be fed, where after remaining a quarter of an hour, each mess is obliged to give place to the next in rotation.

[4] It may perhaps be conceived, from the crouded state in which the Slaves appear in the Plate, that an unusual and exaggerated instance has been produced; this, however, is so far from being the case, that no ship, if her intended cargo can be procured, ever carries a less number than one to a Ton, and the usual practice has been to carry nearly double that number: The Bill which was passed during the last Session of Parliament, only restricts the carriage to five Slaves for three tons; and the Brooks, of Liverpool, a capital ship, from which the above sketch was proportioned, did, in one voyage actually carry 609 Slaves, which is more than double the number that appear in the Plate.—The mode of stowing them was a follows—Platforms, or wide shelves were erected, between the decks, extending so far from the sides towards the middle of the vessel, as to be capable of containing four additional rows of Slaves, by which means the perpendicular height between each tier, after allowing for the beams and the platforms, was reduced to two feet six inches; for they could not even fit in an erect posture; besides which, in the Men’s apartment, instead of four rows; five were stowed by placing the heads of one between the thighs of another. —All the horrors of this situation are still multiplied in the smaller vessels. The Kitty, of 127 tons, had one foot ten inches and the Venus of 146 tons, only one foot nine inches perpendicular height above each layer.

[5] The above mode of carrying the Slaves, however, is only one, among a thousand other miseries, which those unhappy and devoted creatures suffer from this disgraceful Traffick of the Human Species; which in every part of its progress, exhibits scenes that strike us with horror and indignation.—If we regard the first stage of it on the Continent of Africa, we find that a hundred thousand Slaves are annually produced there for exportation, the greatest part of whom consist of innocent persons, torn from their dearest friends and connections, sometimes by force, and sometimes by treachery. Of these, experience has shewn, that five and forty thousand perish, either in the dreadful mode of conveyance before described, or within two years after their arrival at the plantations, before the are seasoned to the climate.—Those who unhappily survive these hardships, are destined, like their beasts of burden, to exhaust their lives in the unremitting labours of a Slavery, without recompence, and without hope.

[6] The inhumanity of this Trade, indeed, is so notorious, and so universally admitted, that even the advocates for the continuance of it, have rested all their arguments on the political inexpediency of its abolition; and in order to strengthen a weak cause, have either maliciously or ignorantly confounded together the emancipation of the Negroes already in Slavery, with the abolition of the Trade; and thus many well-meaning people have become enemies of the cause, by the apprehensions, that private property will be materially injured by the success of it.—To such, it becomes a necessary information, that liberating the Slaves forms no part of the present system; and so far will the prohibition of a future trade be from injuring private property, that the value of every Slave will be very considerably increased, from the moment that event takes place, and a more kind and tender treatment will immediately be insured to them by their Masters, from the necessity every planter will then be under to keep up his stock, by natural means; a practice which some humane inhabitants of the Islands have pursued with the greatest success, and upon whose estates no new Negroes have been purchased for a number of years, the death vacancies having been supplied by young ones, born and bred in their own plantations.—Thus then the value of private property will not only su≠er no diminution, but will be very considerably inhanced by the abolition of the Trade.—It now only remains to see how the Public and the Slave Merchants will be affected by it.

[7] It is said by the well wishers to this Trade, that the suppression of it will destroy a great nursery for seamen, and annihilate a very considerable source of commercial profit.—In answer to these objects, Mr. Clarkson, in his admirable treatise on the impolicy of the Trade, lays down two positions, which he has proved from the most incontestible authority.—First, that so far from being a Nursery, it has been constantly and regularly a Grave for our Seamen; for that in this Traffick only, more Men perish in ONE Year, than in all the other Trades of Great-Britain in TWO Years: And, secondly, that the balance of the trade, from its extreme precariousness and uncertainty, is so notoriously against the Merchants, that if all the vessels employed in it were the property of one man, he would infallibly, at the end of their voyages, find himself a loser.

[8] As then the Cruelty and Inhumanity of this Trade must be universally admitted and lamented, and as the policy or impolicy of its abolition is a question which the wisdom of the Legislature must ultimately decide upon, and which it can only be enabled to form a just estimate of, by the most thorough investigation on all its relations and dependencies; it becomes the indispensible duty of every friend to humanity, however his speculations may have led him to conclude on the political tendency of the measure, to stand forward and to assist the Committees, either by producing such facts as he may himself be acquainted with, or by subscribing, to enable them to procure and transmit to the Legislature, such evidence as will tend to throw the necessary lights on the subject.—And people would do well to consider that it does not often fall to the lot of individuals, to have an opportunity of performing so important a moral and religious duty, as that of endeavouring to put an end to a practice, which may, without exaggeration, be stiled one of the greatest evils at this day existing upon the earth.

By the Plymouth Committee,

W. Elford, Chairman. N.B.

Subscriptions are received at the Plymouth, Naval, and Western Banks.

A portion of Equiano’s published letter to the Plymouth Committee commends the sentiments of the final paragraph by reiterating them, albeit in more concise and rhetorically effective language:

It is the duty of every man, every friend to religion and humanity, to assist the different Committees engaged in this pious work; reflecting that it does not often fall to the lot of individuals to contribute to so important a moral and religious duty as that of putting an end to a practise which may, without exaggeration, be stiled one of the greatest evils now existing on earth.

Excerpted from Committed to Memory: The Art of the Slave Ship Icon by Cheryl Finley. Copyright © 2018 by Princeton University Press. Reprinted by permission.