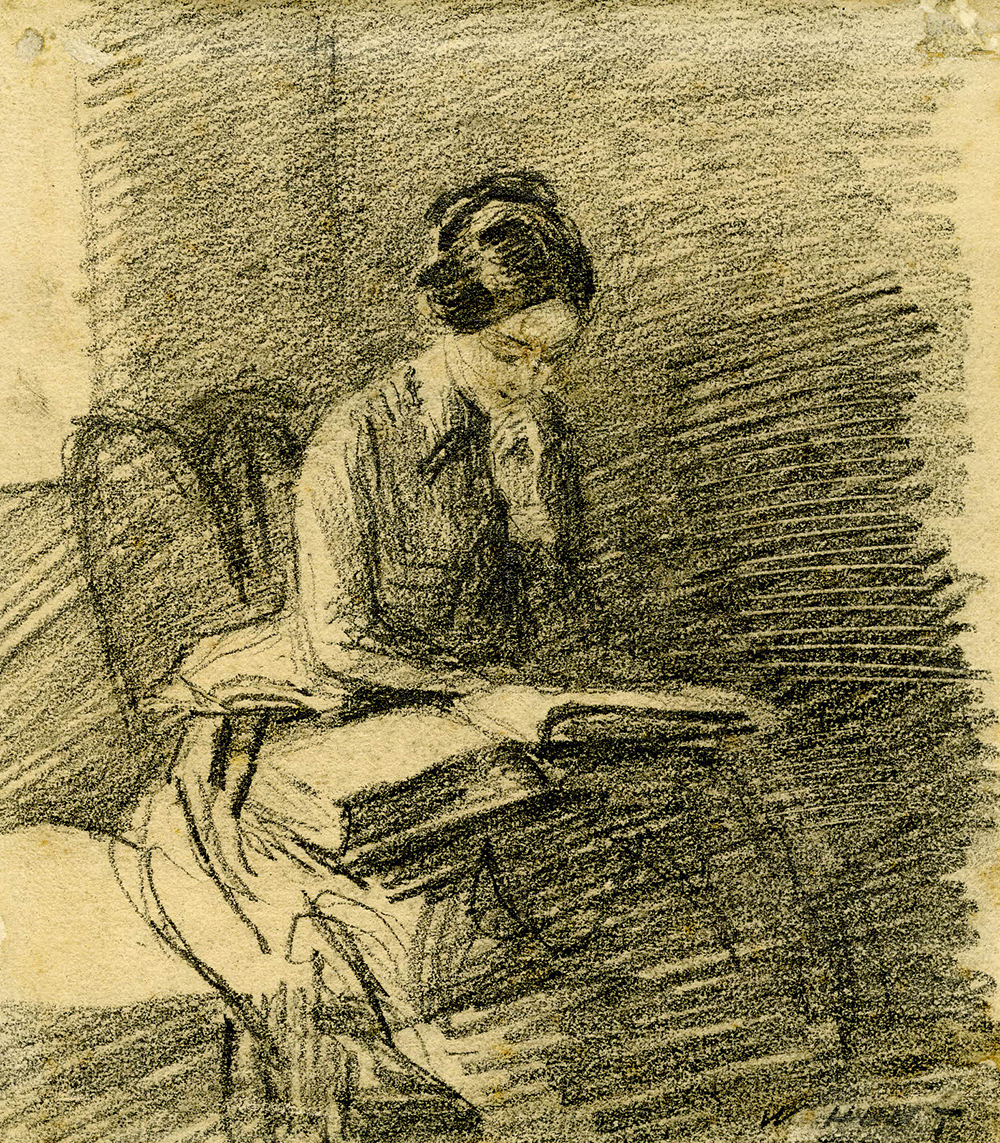

Light Reading, c. 1860. The J. Paul Getty Museum.

For some readers, finding time really doesn’t seem to be a problem. Elizabeth Griffith (her maiden name) and Richard Griffith married in 1751 after a turbulent and loquacious courtship involving the exchange of hundreds of letters. Those letters, which they began to publish jointly six years later as A Series of Genuine Letters between Henry and Frances, document their different but equally busy lives—Richard’s as a small Irish landowner, and Elizabeth’s as the daughter of a theatrical family in Dublin. Both were informally educated and both were limited in their financial means, constrained throughout their lives by the need to earn money. During the course of their marriage, each wrote novels, Elizabeth wrote plays, and Richard published some collections of essays while he pursued business opportunities in different parts of the country. But Elizabeth and Richard also found the opportunity to read books in abundance. Their early letters are full of French and Latin quotations and references to the texts that they read and approve in tandem: Montaigne, Pliny, Seneca, Shakespeare, and Addison. In one letter, Richard writes: “I am, at present, sitting in the middle of a large Field of Barley and am taking care of the Binders and stackers: there are forty-seven Women and fourteen Men, at work round me, while I am reading Pliny, and writing to you.”

Richard, who never really settled down to one form of employment and whose attention remained jittery to the end, often reads texts out of order, and generally seems familiar with texts’ parts rather than their whole. He is quite up-front about this style of study being his preferred mode and openly declares himself unsuited to devoting longer stretches of time to texts. We should not think of the scene in the barley field as a compromise on a more dedicated scene of reading he’d have liked more. “In Truth,” he writes of his own productions in the preface to the second edition of A Series of Genuine Letters, “I have never attempted any Thing which exceeded the length of a Page or two: I grow scant of Breath; I have not a Fund of Literature to deal by wholesale and am therefore obliged to retail my stocks and scraps; and perhaps if all Writers would confine themselves to a more laconic Method, it might save readers from misemploying a great deal of precious Time.” This description fits the style of his brief pieces, many of which he presents in no particular order. The reading that Richard recommends to Elizabeth, and which the prefatory material to the Genuine Letters recommends to their reader, entails a gentle, non-purposive browsing rather than obedience to pagination or a book’s entirety. At one point Richard sends Elizabeth the seventeenth-century text Employment of Time, recommending it as a collection of pieces rather than a continuous essay. “Read the preface last,” he adds, confirming his taste in books as things to be browsed and sampled rather than consumed in linear terms.

Recent work in book and media history suggests that Richard Griffith was probably quite typical in dipping into and flicking through books. Brad Pasanek, author of Metaphors of Mind: An Eighteenth-Century Dictionary, reminds us that desultory reading was common practice in the eighteenth century. He invokes Samuel Johnson, who, when asked if he’s ever done more than dip into a book, is said to have answered: “No, Sir, so you read books through?” Pasanek stresses that the casual reading practices of eighteenth-century readers were truer than we might imagine in this perspective to the Latin word for reading (legere), which emphasizes “picking, choosing, selecting, collecting, and enumerating.” The grazing habits of a reader like Richard were self-consciously so: he describes himself possessed of “a sort of heterogenous knowledge, a kind of dictionary literature” that he acquired through “miscellenous [sic] learning, picked up here and there, sparga coegi, as [he] could borrow books.” Pasanek’s approach also confirms that books were not always treated as rigorously or as studiously as my case studies so far have suggested.

The version of light reading most famously feared in the period was one in which a reader (usually a woman) gets swept up in fiction, carried away by romance. “It must be a matter of real concern to all considerate minds,” wrote Samuel Pegge in 1767, “to see the youth of both sexes passing so large a part of their time in reading that deluge of familiar romances, which, in this age, our island overflows with. ’Tis not only a most unprofitable way of spending time, but extremely prejudicial to their morals, many a young person being entirely corrupted by the giddy and fantastical notions of love and gallantry, imbibed from thence.” In this equation, reading diverts the reader from worthier activities. The book competes for time by being more linear, and more suspenseful, than everyday life. It takes the reader hostage to the turning of one page after another. But Richard, like most desultory readers, was not particularly enamored with fiction or plot. When Elizabeth recommends Tom Jones, Richard reads it and writes back to say he is not impressed. Finding time for reading in his case does not rely on books being compelling in ways that make their consumption inevitable, but on their being to hand as pages to be used and accessed at his own speed. Approaching books as nonlinear and easily accessible introduces a temporal economy very different from the one that comes with thinking of them as long or compulsively forward-moving.

Richard’s letters and essays show that his handling of books is linked to the way he treats actual events. A plot or a love affair could go one way—or it could go another. As readers, and as lovers, the Griffiths embrace their options without appearing overwhelmed by them. But they are, for all this, book readers, not internet browsers. It matters that books exist in a given form, that they are invitations, to use political scientist Davide Panagia’s terms, “to think otherwise of givenness” rather to embrace absolute open-endedness. For the Griffiths, book reading brings to light a multitude of possible pathways without requiring all of them to be followed at once. Plots and arguments written and bound in one way, and yet accessible as combinations that could be different, imply that the read book is an entity quite different in this capacity from the unread one, which seems, if anything, to represent time as more linear than in real life. The book’s fixed arrangement, its boundness and sequentiality, play into this sense of time being a field of variation and flexibility rather than lack. The Griffiths themselves approach their marriage creatively as readers, publishing their own love letters as things to be read out of order and opened randomly at any page.

Once Genuine Letters began to appear in volumes and editions six years into their marriage, readers were given access to selections of their correspondence. Their letters were read from the outset as real and not as an epistolary novel. Interest in them was high: the first volumes went through multiple editions even before the last volume appeared in 1770. That popularity is also fairly easily explained: Richard and Elizabeth are lively, witty correspondents, caught up in genuine struggles over power and their future, and unusually open about the various forms their intimacy could take. Elizabeth, in particular, writes with energy and strength about her own position as a woman, and about the importance of women’s education. “I interdict you,” she writes in an early letter to Richard, “from the unjustness of any satire against our sex, till you have, by a proper and more liberal education, given our noble and ingenious natures fair play to exert themselves. Do this, if ye dare, ye imperious tyrants, and ye shall see, how small we will make you.” Such exchanges display Elizabeth as highly literate but not privileged, unconventional but careful about her relationship with Richard. During the early years of their correspondence the question of marriage could hardly be raised, so impossible did it seem that they could fund their lives together. While Richard lobbies for an erotic relationship—“My desire points North, in the direction of your Chastity”—Elizabeth writes boldly of other kinds of love: “That I love you, I own, and confess it more freely, since I find I have, thank God, sufficient strength to acknowledge it with safety; for I am glad to find, I do not love you better than myself, and, tho’ I would cheerfully sacrifice all that is perishable to me, for you happiness, I shall take care to preserve that part of me, which may make you, at some time in your life, not ashamed of having loved me.” In response, Richard opens up to her about his friendships with other women, his preference for the company of women over men, and previous relationships he has had. At one point, he recycles a poem he’s written for another lover, and sends Elizabeth jewelry he’d given to and had returned by a woman he’d once loved. But he’s charming too, particularly in his support of Elizabeth’s gifts as a writer. Richard is fairly candid about his own short span of attention, and he presents himself in A Series of Genuine Letters as unable to follow the thread of an argument or a course of learning along conventional lines: “My writing, like my life, has been ex tempore, and with as little parsimony. I have sometimes crouded as many hints into one letter as would have served a French wire-drawer to frame a dozen essays out of. I have lived with precipitation, and all my oeconomy has been for the future: I have many subjects in contemplation, but never proceeded further than a few minutes; I have not patience or servility to trail a thought in leading strings.”

In curating their letters, Richard and Elizabeth eschew the suggestion of their relationship being in any way linear. Instead the letters give the impression of a secure relationship, one that can be opened at almost any point, and read in any order, and reissued. Its outcome is assured. But, with this in mind, random access is good, disordered reading is good, and disassociated readings are good. All of these modes of reading correspond to the state of marriage as Richard describes it, as one that “preserves its knot intire” despite wanderings and reversals. It confirms the acute sense that he and Elizabeth maintain in writing to each other for four years before their marriage that things might have been otherwise. Being asked about one’s partnership in modern terms is as likely to require an answer invoking contingency as fate. This analogy is as naturally accommodated by the interface of the book as Elizabeth and Richard Griffith’s experience as readers, writers, and editors complicates the idea of print reading, either as competing directly for everyday time, or as giving us a faster and more compelling version of linear time. The combination of fixity and openness that they perceive in the book, and the sense of contingency that this brings to scenes of its real and imagined reading, relies on one course of events being written down. But it also relies on time, not so much time to read, but time as the imagined vector along which unpredictability returns to books as they are opened and read in many constellations.

Excerpted from Reading and the Making of Time in the Eighteenth Century by Christina Lupton. Published by Johns Hopkins University Press. Copyright © 2018 by Johns Hopkins University Press. Reprinted by permission of the publisher.