No law is sufficiently convenient to all.

—Roman proverb,Order in the Court

Alice confronts legal jabberwocky.

The King and Queen of Hearts were seated on their throne when they arrived, with a great crowd assembled about them—all sorts of little birds and beasts, as well as the whole pack of cards; the knave was standing before them, in chains, with a soldier on each side to guard him; and near the king was the white rabbit, with a trumpet in one hand and a scroll of parchment in the other.

In the very middle of the court was a table with a large dish of tarts upon it; they looked so good that it made Alice quite hungry to look at them—“I wish they’d get the trial done,” she thought, “and hand around the refreshments!” But there seemed to be no chance of this, so she began looking at everything about her to pass away the time.

Alice had never been in a court of justice before, but she had read about them in books, and she was quite pleased to find that she knew the name of nearly everything there. “That’s the judge,” she said to herself, “because of his great wig.”

The judge, by the way, was the king; and as he wore his crown over the wig, he did not look at all comfortable, and it was certainly not becoming.

“And that’s the jury box,” thought Alice, “and those twelve creatures,” (she was obliged to say “creatures,” you see, because some of them were animals and some were birds), “I suppose they are the jurors.”

“Herald, read the accusation!” said the king.

On this the white rabbit blew three blasts on the trumpet, and then unrolled the parchment scroll and read as follows:

The Queen of Hearts, she made some tarts,

All on a summer day:

The Knave of Hearts, he stole those tarts,

And took them quite away!

“Consider your verdict,” the king said to the jury.

“Not yet, not yet!” the rabbit hastily interrupted. “There’s a great deal to come before that!”

“Call the first witness,” said the king, and the white rabbit blew three blasts on the trumpet and called out, “First witness!”

The first witness was the hatter. He came in with a teacup in one hand and a piece of bread and butter in the other. “I beg pardon, Your Majesty,” he began, “for bringing these in, but I hadn’t quite finished my tea when I was sent for.”

“You ought to have finished,” said the king. “When did you begin?”

The hatter looked at the March hare, who had followed him into the court, arm in arm with the dormouse. “Fourteenth of March, I think it was,” he said.

“Fifteenth,” said the March hare.

The Lawyer’s Last Circuit, by Thomas Rowlandson, 1802. Courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington, Rosenwald Collection.

“Sixteenth,” added the dormouse.

“Write that down,” the king said to the jury, and the jury eagerly wrote down all three dates on their slates, and then added them up.

Just at this moment Alice felt a very curious sensation, which puzzled her a good deal until she made out what it was: she was beginning to grow larger, and she thought at first she would get up and leave the court; but on second thought she decided to remain where she was as long as there was room for her.

“I wish you wouldn’t squeeze so,” said the dormouse, who was sitting next to her. “I can hardly breathe.”

“I can’t help it,” said Alice very meekly. “I’m growing.”

“You’ve no right to grow here,” said the dormouse.

“Don’t talk nonsense,” said Alice more boldly, “you know you’re growing, too.”

“Yes, but I grow at a reasonable pace,” said the dormouse, “not in that ridiculous fashion.” And he got up very sulkily and crossed over to the other side of the court.

“Call the next witness!” said the king.

Alice watched the white rabbit as he fumbled over the list, feeling very curious to see what the next witness would be like, “—for they haven’t got much evidence yet,” she said to herself. Imagine her surprise when the white rabbit read out, at the top of his shrill little voice, the name “Alice!”

“Here!” cried Alice, quite forgetting in the flurry of the moment how large she had grown in the last few minutes, and she jumped up in such a hurry that she tipped over the jury box with the edge of her skirt.

“Oh, I beg your pardon!” she exclaimed in a tone of great dismay and began picking them up again as quickly as she could, for she had a vague sort of idea that they must be collected at once and put back into the jury box or they would die.

“The trial cannot proceed,” said the king in a very grave voice, “until all the jurymen are back in their proper places—all,” he repeated with great emphasis, looking hard at Alice as he said so.

Alice looked at the jury box and saw that, in her haste, she had put the lizard in head downward, and the poor little thing was waving its tail about in a melancholy way, being quite unable to move. She soon got it out again and put it right; “not that it signifies much,” she said to herself; “I should think it would be quite as much use in the trial one way up as the other.”

As soon as the jury had a little recovered from the shock of being upset, and their slates and pencils had been found and handed back to them, they set to work very diligently to write out a history of the accident, all except the lizard, who seemed too much overcome to do anything but sit with its mouth open, gazing up into the roof of the court.

“What do you know about this business?” the king said to Alice.

Do what thou wilt shall be the whole of the law.

—Aleister Crowley, 1904“Nothing,” said Alice.

“That’s very important,” the king said, turning to the jury. They were just beginning to write this down on their slates when the white rabbit interrupted. “Unimportant, Your Majesty means, of course,” he said in a very respectful tone, but frowning and making faces at him as he spoke.

“Unimportant, of course, I meant,” the king hastily said, and went on to himself in an undertone, “important—unimportant—unimportant—important—” as if he were trying which word sounded best.

Some of the jury wrote it down “important” and some “unimportant.” Alice could see this, as she was near enough to look over their slates; “but it doesn’t matter a bit,” she thought to herself.

At this moment the king, who had been for some time busily writing in his notebook, cackled out, “Silence!” and read out from his book, “Rule forty-two: All persons more than a mile high to leave the court.”

Everybody looked at Alice.

“I’m not a mile high,” said Alice.

“You are,” said the king.

“Nearly two miles high,” added the queen.

“Well, I shan’t go, at any rate,” said Alice, “besides, that’s not a regular rule; you invented it just now.”

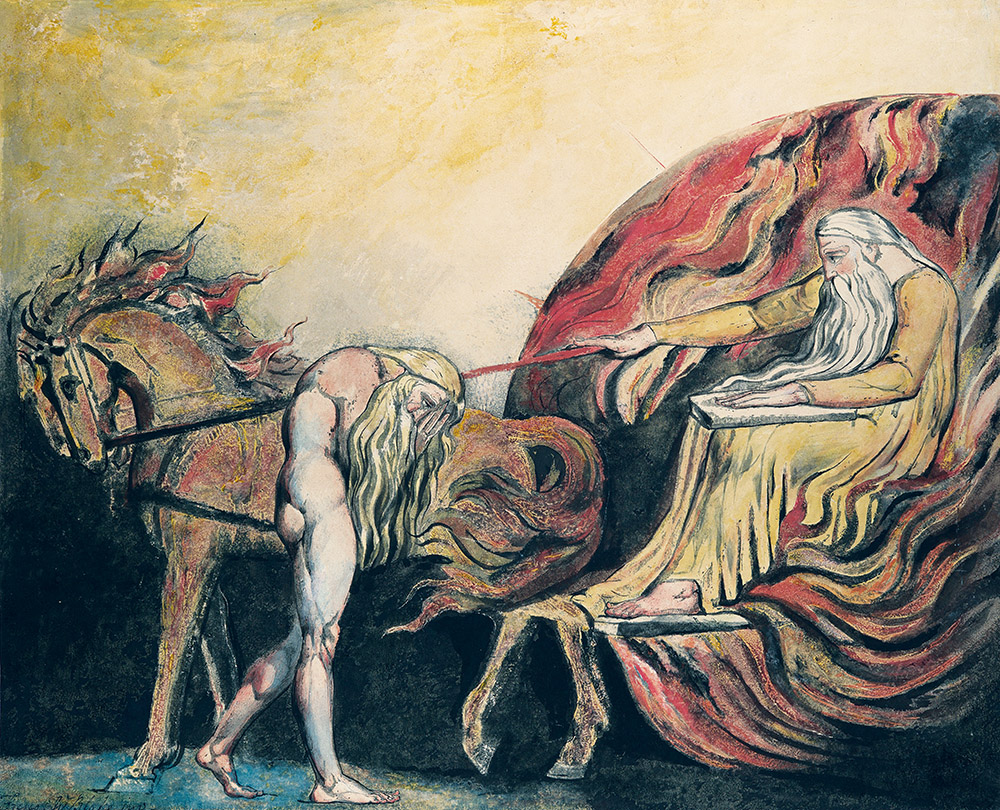

God Judging Adam, by William Blake, c. 1795. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rogers Fund, 1916.

“It’s the oldest rule in the book,” said the king.

“Then it ought to be number one,” said Alice.

The king turned pale and shut his notebook hastily. “Consider your verdict,” he said to the jury in a low, trembling voice.

“No, no!” said the queen. “Sentence first—verdict afterward.”

“Stuff and nonsense!” said Alice loudly. “The idea of having the sentence first!”

“Hold your tongue!” said the queen, turning purple.

“I won’t!” said Alice.

“Off with her head!” the queen shouted at the top of her voice. Nobody moved.

“Who cares for you?” said Alice (she had grown to her full size by this time). “You’re nothing but a pack of cards!”

At this the whole pack rose up into the air and came flying down upon her; she gave a little scream, half of fright and half of anger, and tried to beat them off, and found herself lying on the bank with her head in the lap of her sister, who was gently brushing away some dead leaves that had fluttered down from the trees upon her face.

Lewis Carroll

From Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. A mathematician and photographer as well as a writer, Carroll (né Charles Dodgson) first told his story about a girl falling down a rabbit hole to Alice Liddell, the four-year-old daughter of Oxford dean Henry George Liddell. Many characters in Carroll’s Wonderland stories are based on figures from the Liddell household, including Dinah the cat. The Queen of Hearts, it has been suggested, was inspired by Alice’s mother, with whom Carroll sustained a mutually suspicious relationship.