The one thing the world will never have enough of is the outrageous.

—Salvador Dalí, 1953Real Housewives of the Eighteenth Century

The insults unfurl at Lady Sneerwell’s house.

[Lady Sneerwell’s house. Lady Sneerwell, Lady Teazle, Mrs. Candour, Crabtree, and Sir Benjamin Backbite. Servants attending with tea.]

Mrs. Candour: Now, I’ll die, but you are so scandalous, I’ll forswear your society.

Lady Teazle: What’s the matter, Mrs. Candour?

Mrs. Candour: They’ll not allow our friend, Miss Vermilion, to be handsome.

Lady Sneerwell: Oh, surely, she’s a pretty woman.

Crabtree: I am very glad you think so, madam.

Mrs. Candour: She has a charming fresh color.

Lady Teazle: Yes, when it is fresh put on.

Mrs. Candour: Oh, fie! I’ll swear her color is natural, I have seen it come and go.

Lady Teazle: I dare swear you have, ma’am; it goes off at night, and comes again in the morning.

Sir Benjamin: True, ma’am, it not only comes and goes, but what’s more, egad, her maid can fetch and carry it!

Mrs. Candour: How I hate to hear you talk so! But surely, now, her sister is, or was, very handsome.

Crabtree: Who? Mrs. Evergreen? O Lord! She’s six and fifty if she’s an hour!

Mrs. Candour: Now positively you wrong her; fifty-two or fifty-three is the utmost—and I don’t think she looks more.

Sir Benjamin: Ah! There’s no judging by her looks, unless one could see her face.

Lady Sneerwell: Well, well, if Mrs. Evergreen does take some pains to repair the ravages of time, you must allow she effects it with great ingenuity; and surely that’s better than the careless manner in which the widow Ochre caulks her wrinkles.

Sir Benjamin: Nay, now, Lady Sneerwell, you are severe upon the widow. Come, come, ’tis not that she paints so ill—but when she has finished her face, she joins it on so badly to her neck that she looks like a mended statue, in which the connoisseur may see at once that the head is modern, though the trunk’s antique.

Crabtree: Ha ha ha! Well said, nephew!

Lady Teazle: Here comes Sir Peter to spoil our pleasantry.

[Enter Sir Peter Teazle]

Sir Peter: Ladies, your most obedient—[aside] Mercy on me! Here is the whole set! A character dead at every word, I suppose.

Mrs. Candour: I am rejoiced you are come, Sir Peter. They have been so censorious, they will allow good qualities to nobody. For my part, I own I cannot bear to hear a friend ill spoken of!

Sir Peter: No, to be sure!

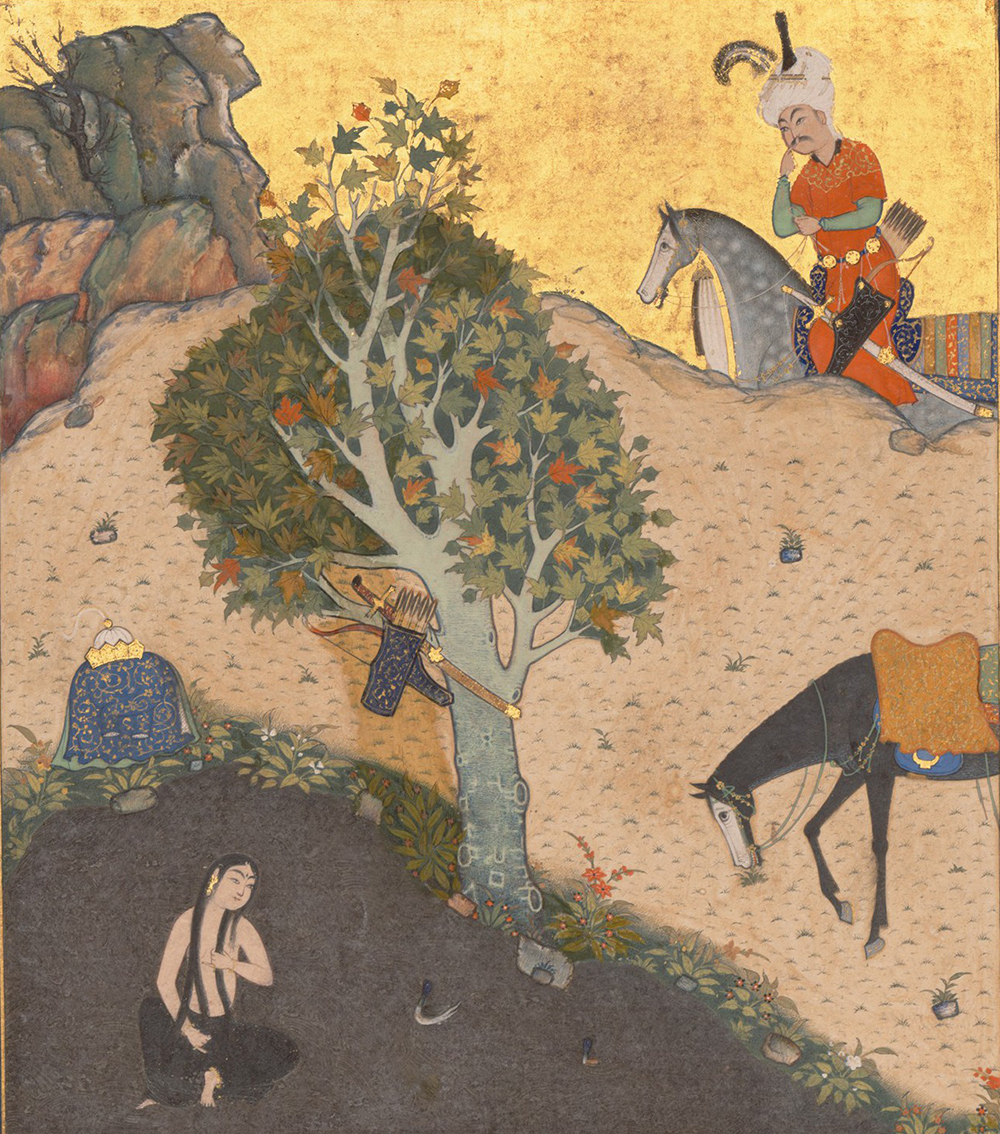

Khusrau Catches Sight of Shirin Bathing, by Shaikh Zada, c. 1524. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Alexander Smith Cochran, 1913.

Sir Benjamin: And Mrs. Candour is of so moral a turn, she can sit for an hour and hear Lady Stucco talk sentiments.

Lady Teazle: Nay, I vow Lady Stucco is very well with the dessert after dinner; for she’s just like the French fruit one cracks for mottoes—made up of paint and proverb.

Mrs. Candour: Well, I never will join in ridiculing a friend; and so I constantly tell my cousin Ogle, and you all know what pretensions she has to be critical on beauty.

Crabtree: Oh, to be sure! She has herself the oddest countenance that ever was seen; ’tis a collection of features from all the different countries of the globe.

Sir Benjamin: So she has, indeed—an Irish front—

Crabtree: Caledonian locks—

Sir Benjamin: Dutch nose—

Crabtree: Austrian lip—

Sir Benjamin: Complexion of a Spaniard—

Crabtree: And teeth à la Chinoise—

Sir Benjamin: In short, her face resembles a table d’hôte at Spa—where no two guests are of a nation—

Crabtree: Or a congress at the close of a general war—wherein all the members, even to her eyes, appear to have a different interest, and her nose and chin are the only parties likely to join issue.

Mrs. Candour: Ha ha ha!

Sir Peter: [aside] Mercy on my life!—a person they dine with twice a week.

Lady Sneerwell: Go, go; you are a couple of provoking toads.

Mrs. Candour: Nay, but I vow you shall not carry the laugh off so; for give me leave to say that Mrs. Ogle—

Sir Peter: Madam, madam, I beg your pardon—there’s no stopping these good gentlemen’s tongues. But when I tell you, Mrs. Candour, that the lady they are abusing is a particular friend of mine, I hope you’ll not take her part.

Lady Sneerwell: Well said, Sir Peter! But you are a cruel creature—too phlegmatic yourself for a jest, and too peevish to allow wit in others.

Sir Peter: Ah! Madam, true wit is more nearly allied to good nature than your ladyship is aware of.

Lady Teazle: True, Sir Peter. I believe they are so near akin that they can never be united.

Sir Benjamin: Or rather, madam, suppose them to be man and wife, because one seldom sees them together.

Lady Teazle: But Sir Peter is such an enemy to scandal, I believe he would have it put down by Parliament.

Sir Peter: ’Fore heaven, madam, if they were to consider the sporting with reputation of as much importance as poaching on manors, and pass an Act for the Preservation of Fame, I believe there are many would thank them for the bill.

Lady Sneerwell: O Lud! Sir Peter, would you deprive us of our privileges?

Sir Peter: Aye, madam; and then no person should be permitted to kill characters and run down reputations but qualified old maids and disappointed widows.

Lady Sneerwell: Go, you monster!

Mrs. Candour: But surely you would not be quite so severe on those who only report what they hear?

Sir Peter: Yes, madam, I would have law merchant for them, too; and in all cases of slander currency, whenever the drawer of the lie was not to be found, the injured parties should have a right to come on any of the endorsers.

Crabtree: Well, for my part, I believe there never was a scandalous tale without some foundation.

Lady Sneerwell: Come, ladies, shall we sit down to cards in the next room?

[Enter Servant, who whispers to Sir Peter]

Sir Peter: I’ll be with them directly.

[Exit Servant]

[aside] I’ll get away unperceived.

Lady Sneerwell: Sir Peter, you are not going to leave us?

Sir Peter: Your ladyship must excuse me; I’m called away by particular business. But I leave my character behind me.

[Exit Sir Peter]

Sir Benjamin: Well—certainly, Lady Teazle, that lord of yours is a strange being; I could tell you some stories of him would make you laugh heartily—if he were not your husband.

Lady Teazle: Oh, pray don’t mind that—come do let’s hear them.

[Joins the rest of the company going into the next room.]

Richard Brinsley Sheridan

From The School for Scandal. In his early twenties, Sheridan abandoned his legal studies to follow in the footsteps of his mother, a playwright, and his father, a theater manager. His first play, The Rivals, was a failure upon its debut in 1775, prompting him to rewrite it. By contrast, The School for Scandal was an immediate success when it premiered two years later, by which time Sheridan had become friends with Fanny Burney, Samuel Johnson, and Edmund Burke. In 1780 he entered Parliament as a Whig representing Stafford, a seat he held for thirty-two years.