Recreations should be as sauces to your meat, to sharpen your appetite unto the duties of your calling, and not to glut yourselves with them.

—Thomas Gouge, 1672Lucian Asks, Why Sports?

Discussing the purpose of athletics.

Anacharsis: Why do your young men behave like this, Solon? Some of them grappling and tripping each other, some throttling, struggling, intertwining in the clay like so many pigs wallowing. And yet their first proceeding after they have stripped—I noticed that—is to oil and scrape each other quite amicably; but then I do not know what comes over them—they put down their heads and begin to push, and crash their foreheads together like a pair of rival rams. There, look! That one has lifted the other right off his legs and dropped him on the ground; now he has fallen on top and will not let him get his head up, but presses it down into the clay; and to finish him off he twines his legs tight round his belly, thrusts his elbow hard against his throat, and throttles the wretched victim, who meanwhile is patting his shoulder—that would be a form of supplication—he is asking not to be quite choked to death. Regardless of their fresh oil, they get all filthy, smother themselves in mud and sweat till they might as well not have been anointed, and present, to me at least, the most ludicrous resemblance to eels slipping through a man’s hands.

Then here in the open court are others doing just the same, except that instead of the clay they have for floor a depression filled with deep sand, with which they sprinkle one another, scraping up the dust on purpose, like fowls. I suppose they want their interlacings to be tighter; the sand is to neutralize the slipperiness of the oil, and by drying it up to give a firmer grip.

And here are others, sanded too, but on their legs, going at each other with blows and kicks. We shall surely see this poor fellow spit out his teeth in a minute; his mouth is all full of blood and sand; he has had a blow on the jaw from the other’s fist, you see. Why does not the official there separate them and put an end to it? I guess that he is an official from his purple, but no, he encourages them and commends the one who gave that blow.

Wherever you look, every one busy—rising on his toes, jumping up and kicking the air, or something.

Now I want to know what is the good of it all. To me it looks more like madness than anything else. It will not be very easy to convince me that people who behave like this are not wrong in their heads.

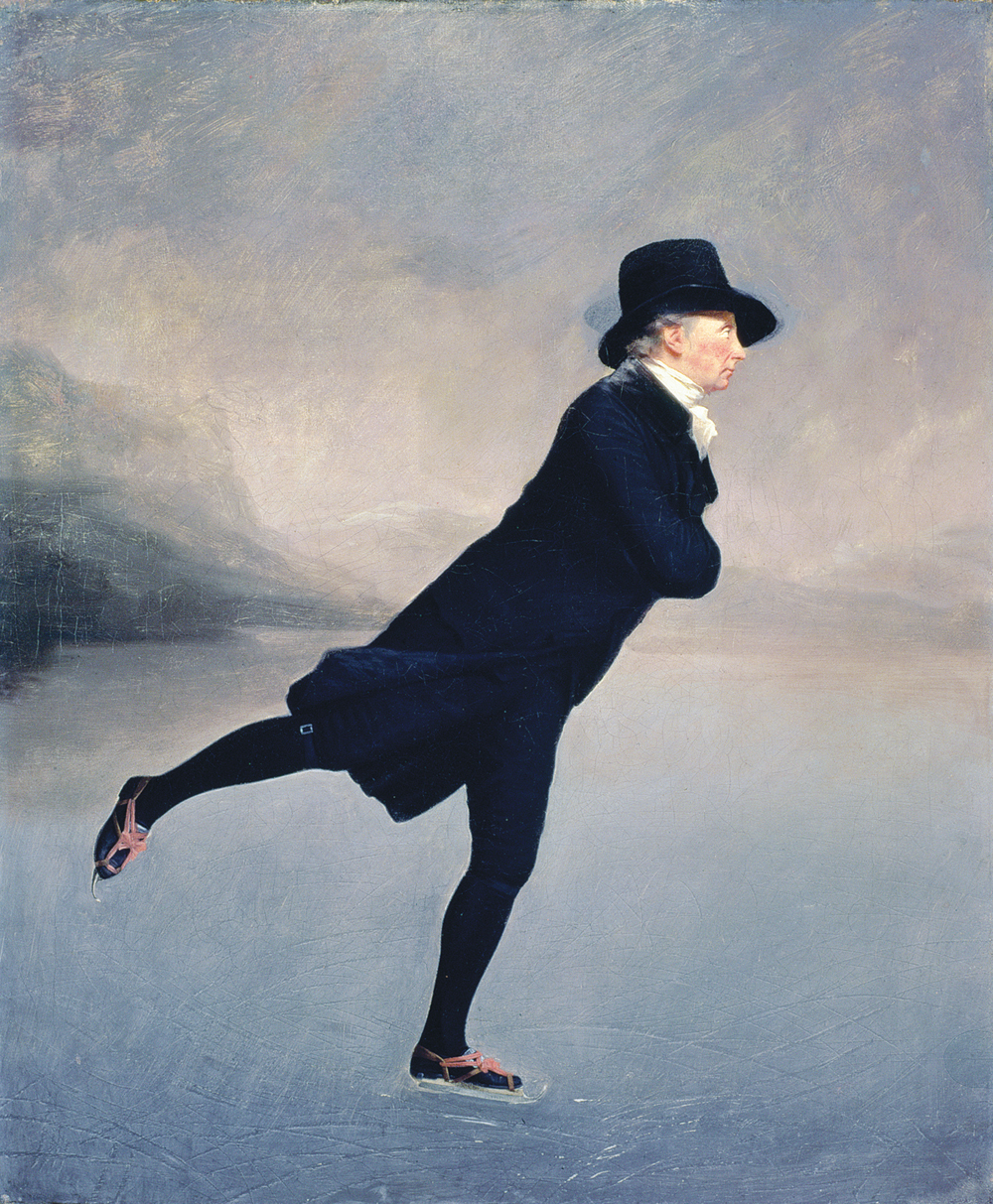

Rev. Robert Walker Skating on Duddingston Loch, by Sir Henry Raeburn, c. 1781. Scottish National Gallery, Edinburgh, Scotland.

Solon: It is quite natural it should strike you that way, being so novel and so utterly contrary to Scythian customs. Similarly you have no doubt many methods and habits that would seem extraordinary enough to us Greeks if we were spectators of them as you now are of ours. But be reassured, my dear sir, these proceedings are not madness; it is no spirit of violence that sets them hitting each other, wallowing in clay, and sprinkling dust. The thing has its use, and its delight too, resulting in admirable physical condition. If you make some stay, as I imagine you will, in Greece, you are bound to be either a clay bob or a dust bob before long; you will be so taken with the pleasure and profit of the pursuit.

Anacharsis: Hands off, please. No, I wish you all joy of your pleasures and your profits, but if any of you treats me like that, he will find out that we do not wear scimitars for ornament.

But would you mind giving a name to all this? What are we to say they are doing?

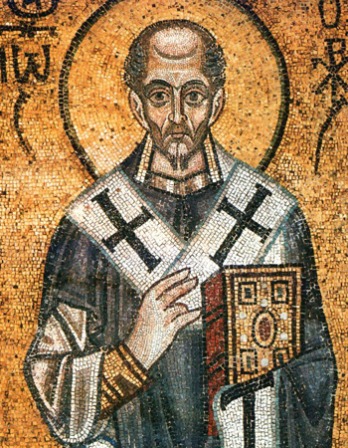

Solon: The place is called a gymnasium, and is dedicated to the Lycian Apollo. You see his statue there, the one leaning on the pillar, with a bow in the left hand. The right arm bent over the head indicates that the god is resting after some great exertion.

Of the exercises here, that in the clay is called wrestling; the youths in the dust are also called wrestlers, and those who strike each other standing are engaged in what we call the pancratium. But we have other gymnasiums for boxing, quoit throwing, and high jumping; and in all these we hold contests, the winner in which is honored above all his contemporaries and receives prizes.

Anacharsis: Ah, and what are the prizes, now?

Solon: At Olympia a wreath of wild olive, at the Isthmus one of pine, at Nemea of parsley, at Pytho some of the God’s sacred apples, and at our Panathenaea, oil pressed from the temple olives. What are you laughing at, Anacharsis? Are the prizes too small?

Anacharsis: Oh dear no; your prize list is most imposing; the givers may well plume themselves on their munificence, and the competitors be monstrous keen on winning. Who would not go through this amount of preparatory toil and take his chance of a choking or a dislocation for apples or parsley? It is obviously impossible for anyone who has a fancy to a supply of apples, or a wreath of parsley or pine, to get them without a mud plaster on his face, or a kick in the stomach from his competitor.

Solon: My dear sir, it is not the things’ intrinsic value that we look at. They are the symbols of victory, labels of the winners; it is the fame attached to them that is worth any price to their holders; that is why the man whose quest of honor leads through toil is content to take his kicks. No toil, no honor; he who covets that must start with enduring hardship—when he has done that, he may begin to look for the pleasure and profit his labors are to bring.

Anacharsis: Which pleasure and profit consists in their being seen in their wreaths by everyone and congratulated on their victory by those who before commiserated their pain; their happiness lies in their exchange of apples and parsley for toil.

Solon: Ah, you certainly do not understand our ways yet. You will revise your opinions before long, when you go to the great festivals and see the crowds gathering to look on, the stands filling up, the competitors receiving their ovations, and the victor being idolized.

Anacharsis: Why Solon, that is just where the humiliation comes in; they are treated like this not in something like privacy, but with all these spectators to watch the affronts they endure—who, I am to believe, count them happy when they see them dripping with blood or being throttled, for such are the happy concomitants of victory. In my country, if a man strikes a citizen, knocks him down, or tears his clothes, our elders punish him severely, even though there were only one or two witnesses, not like your vast Olympic or Isthmian gatherings. However, though I cannot help pitying the competitors, I am still more astonished at the spectators; you tell me the chief people from all over Greece attend; how can they leave their serious concerns and waste time on such things? How they can like it passes my comprehension—to look on at people being struck and knocked about, dashed to the ground, and pounded by one another.

Solon: If the Olympia, Isthmia, or Panathenaea were only on now, those object lessons might have been enough to convince you that our keenness is not thrown away. I cannot make you apprehend the delights of them by description; you should be there sitting in the middle of the spectators, looking at the men’s courage and physical beauty, their marvelous condition, effective skill, and invincible strength—their enterprise, their emulation, their unconquerable spirit, and their unwearied pursuit of victory. Oh, I know very well, you would never have been tired of talking about your favorites, backing them with voice and hand.

Anacharsis: I dare say—and with laugh and flout too. All the fine things in your list, your courages and conditions, your beauties and enterprises, I see you wasting in no high cause; your country is not in danger, your land not being ravaged, your friends or relations not being hauled away. The more ridiculous that such patterns of perfection as you make them out should endure the misery all for nothing—and spoil their beauty and their fine figures with sand and black eyes just for the triumphant possession of an apple or a sprig of wild olive. Oh, how I love to think of those prizes! By the way, do all who enter get them?

Solon: No, indeed. There is only one winner.

Anacharsis: And do you mean to say such a number can be found to toil for a remote uncertainty of success, knowing that the winner cannot be more than one, and the failures must be many, with their bruises, or their wounds very likely, for sole reward?

Solon: Dear me; you have no idea yet of what is a good political constitution, or you would never deprecate the best of our customs. If you ever take the trouble to inquire how a state may best be organized and its citizens best developed, you will find yourself commending these practices and the earnestness with which we cultivate them; then you will realize what good effects are inseparable from those toils which seem for the moment to tax our energies to no purpose.

Lucian

From “Anacharsis.” Lucian was an apprentice to a sculptor in his native Syria and a successful rhetorician in Italy and Gaul before settling in Athens, where he became a versatile and prolific author. He wrote various mock tragedies, a treatise on historiography, a critique of Stoicism, and scores of satires, among them Dialogues of the Courtesans and True History.