It was the men I deceived the most that I loved the most.

—Marguerite Duras, 1987Paper Moons

Americans have a genius for the artful dodge, but also an infallible willingness to play the fool.

By Lewis H. Lapham

Scherzo di Follia, by Pierre-Louis Pierson, c. 1861–67. Photograph of Countess Virginia Oldoini Verasis di Castiglione. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gilman Collection, Gift of The Howard Gilman Foundation, 2005.

Americans so dearly love to be fooled.

—Charles Baudelaire

Swindle and Fraud, the vaudeville team of nouns headlining this issue of Lapham’s Quarterly, are old dogs always keen to learn new tricks, and their spirited performance during the Great Recession showcased the attention paid to their studies since the Great Houdini, on the evening of January 7, 1918, vanished a five-ton elephant from the stage of New York’s Hippodrome Theater. The new act for a new century topped up the weight of the production values:

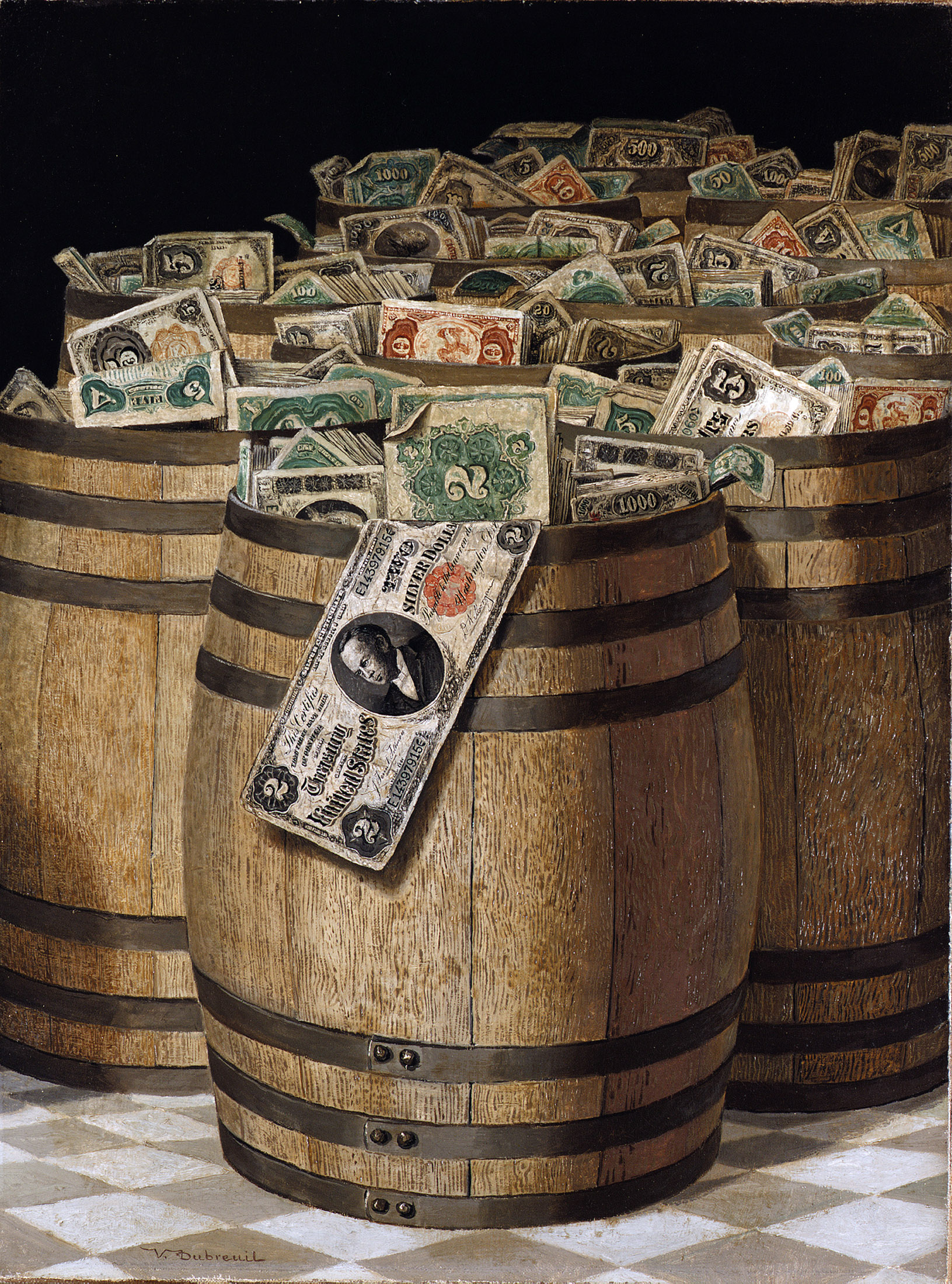

Nine banks emptied of more than $500 billion in capital, as much as $8 trillion withdrawn from the Dow Jones Industrial Average, $2 trillion from the nation’s pension and retirement accounts. Sure-handed juggling of the public trust into the private purse. Stock market touts tap dancing the old soft-shoe with the Securities and Exchange Commission, hedge fund operatives with the Federal Reserve. A cool $1 trillion lifted from the U.S. Treasury in broad daylight, members of Congress working the money-box routine with banks too big to fail.

Throughout the whole of its extended run, the spectacle drew holiday crowds into the circus tents of the tabloid press, and joyous in Mudville was the feasting on fools. Why then the gloom among the wizards of Oz in the upper income brackets of the national news media? One might have hoped for at least a tip of the hat from the Wall Street Journal and The Economist, from Bloomberg News and the American Enterprise Institute. How not exult in the powers of the unfettered free market, admire the entrepreneurial initiative, the scale of the revival of the go-ahead, can-do spirit that made America great?

But instead of disbursing laurels, the guardians at the gates of the country’s moral treasure delivered sermons on the text of American decline, many of them in tune with the one composed by New York Times columnist Thomas Friedman in October 2008, by which time the shearing of the sheep was rolling as merrily along as a Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade.

“The Puritan ethic of hard work and saving still matters,” said Friedman. “We need to get back to collaborating the old-fashioned way. That is, people making decisions based on business judgment, experience, prudence, clarity of communications, and thinking about how—not just how much.”

Barrels of Money, by Victor Dubreuil, c. 1890.

A noble sentiment and no doubt readily available in New England gift shops, but to account for the sacking of the Wall Street temple of Mammon as a falling away from the Puritan work ethic is to misread America’s economic and political history, to mistake the message encoded in the DNA of the American dream. Who among the faithful ever has preferred the bird in the hand to the five in the bush? The spoilsports in the pulpits of spiritual reawakening never lack for proof of shameful behavior and lackluster deportment, but when they call as witness for the prosecution the milk-white marble of Western civilization and the holy scripture of American exceptionalism, they tread on shaky ground.

To storm the walls of Troy the ancient Greeks employed a hollow wooden horse, the ruse sprung full-blown from the head of “nimble-witted” Odysseus, “sacker of cities,” “loved of Zeus.” Sophocles, in the play Philoctetes, asks and answers the question implicated in resorts to trickery:

Neoptolemus: Do you not find it vile yourself, this lying?

Odysseus: Not if the lying brings our rescue with it.

Neoptolemus: How can a man not blush to say such things?

Odysseus: When one does something for gain, one need not blush.

Nor did the founders of the American republic blush to say that the Revolution was in large part won at sea by New England ship captains under license from the Continental Congress to plunder, burn, or sell at auction British vessels bringing munitions and military stores to the king’s regiments quartered in the town of Boston. The colonists at the time had few other means of acquiring weapons with which to give voice to their rebellion. Gen. George Washington, reviewing the situation from his camp in Cambridge in December 1775, understood that his ill-equipped and untried troops were “not likely to do much in the land way” against the superior force of the British Army. It occurred to him to commission a squadron of privateers steered on the compass bearings of stouthearted greed to inflict enough damage on Britain’s overseas trade to persuade the ministers of the crown to abandon the war with the colonies.

For captains able to avoid unlucky shifts in the wind, the rewards were up there in lights with those achieved in the Civil War gold rooms, the 1920s Wall Street rise, and the Internet boom of the 1990s. During the course of the Revolution the winnowing of what came to be known as “the golden harvest” at sea developed from venture-capital start-up to global bonanza. In 1775, as few as ten or twenty small schooners were cruising the Atlantic coast. By 1783, as many as four thousand investment vehicles had been licensed to practice as far offshore as the Mediterranean and the English Channel. The costs more often than not were defrayed by the semblance of a government in Philadelphia, the profits taken by speculators in Boston, Providence, and Marblehead. The contracts earmarked a percentage of the proceeds for the colonial war effort, but the agreements tended to go AWOL when it came time to offload the boodle.

Opponents of the policy thought it unworthy of Christian gentlemen, one apt to lead to “the destruction of the morals of people.” The objections were overruled by advocates of piracy-as-public-service, among them John Joachim Zubly, who informed fellow delegates to the Continental Congress that “it is prudent not to put virtue to too serious a test. I would use American virtue as sparingly as possible, lest we wear it out.”

As Washington had foreseen, the raiding of the lost arks proved to be “the pivot on which everything turned,” but by the time Thomas Jefferson arrived from Paris in 1790 to take up office as America’s first secretary of state, the nap on the cloak of American virtue had been worn as thin as the ice on Walden Pond in April. On being introduced to Alexander Hamilton’s

scheme for setting up a national bank, Jefferson recognized it as one aimed at two objectives: “first, as a puzzle, to exclude popular understanding and inquiry; second, as a machine for the corruption of the legislature.” The latter goal was achieved by inviting members of Congress to buy the government’s discounted certificates of debt with the assurance that the cheap paper would be expensively redeemed at par—“immense sums were thus filched from the poor and ignorant” in order “to keep the legislative in unison with the executive.”

What troubled Jefferson about the scheme was its success: “And with grief and shame it must be acknowledged that his machine was not without effect; that even in this, the birth of our government, some members were found sordid enough to bend their duty to their interests, and to look after personal rather than public good.”

I mention Hamilton not to impugn his character but to suggest that the American genius for the artful dodge in its all-but-infinite variety—the sales pitch, the résumé, the cost overrun, the subprime loan, the building of the transcontinental railroad, the credit default swap, the derivative, the balloon mortgage, the missile gap, the housing bubble, the annual report, the Laffer curve, the Facebook page, the campaign promise, the 2003 invasion of Iraq—is firmly rooted in the country’s founding. The homespun talent arises from the colonial circumstance defined by Daniel Boorstin, the historian and former Librarian of Congress, as one in which “no prudent man dared be too certain of exactly who he was or what he was about; everyone had to be prepared to become someone else.”

The early settlers had little choice in the matter. The making of America was the labor of self-invention, both as public works project and private artisanal enterprise. Absent the rules of a society established on the blueprints of inherited identity and rank, Americans learned from the example of the immortal Odysseus, “great teller of tales,” “man skilled in all ways of contending,” as well as from their instinctive grasp of the wisdom imparted to the duke of Urbino by the Renaissance courtier Niccolò Machiavelli:

“Everyone realizes how praiseworthy it is for a prince to honor his word and to be straightforward rather than crafty in his dealings; nonetheless contemporary experience shows that princes who have achieved great things have been those who have given their word lightly, who have known how to trick men with their cunning, and who, in the end, have overcome those abiding by honest principles…Men are so simple, and so much creatures of circumstance, that the deceiver will always find somebody ready to be deceived.”

The abundance of somebodies ready to be deceived constituted the richest resource on the western shore of the Atlantic Ocean, a blessing more plentiful than the fish in the rivers and the pigeons on the grass. The newly arriving tellers of tales understood themselves to be creatures of their own devising, obliged to trade in the currencies of contrived appearance. The enlightened but impoverished country was short on gold and silver specie, but long on paper moons like those in the song still nearly two hundred years shy of its release date, the ones that “wouldn’t be make-believe if you believed in me.” Which is the deal on the table of the democratic gamble with fortune. We ask for the confidence of our fellow confidence men by way of a fair return on the proposition that all men are created equal, and therefore bound to credit, at face value, one another’s rough-cut improvisations and fanciful masquerades.

The Procession of the Trojan Horse into Troy, by Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo, c. 1760.

The ferocious expansion of the American economy between 1790 and 1860 relied for much of its finance on counterfeit banknotes; among those circulating north and south of the Potomac, more than half were thought to be bogus, but any money was better than no money, and the nation’s better businessmen—preferring a good counterfeit on a solid bank to a genuine bill on a not-so-solid bank—looked upon forgery as a public service. The fairy-tale paper, a commodity likened in 1830 to corn or wheat, was manufactured in bulk in Canada, smuggled south, and marked by different private banks with different designs and denominations (as many as ten thousand by 1860), to secure the promise of American virtue in cloaks of many colors.

The greenback Yankee dollar emerged from the Civil War as the single measure of the saved Union’s good faith. What also emerged from the antebellum mist and smoke was the winsome scoundrel as a figure of popular romance. Herman Melville published

The Confidence Man: His Masquerade on April Fool’s Day in 1857, its setting the steamboat Fidèle bearing south from St. Louis with a full complement of “that multiform pilgrim species, man,”—“men of business and men of pleasure; parlor men and backwoodsmen…heiress-hunters, gold-hunters, buffalo-hunters, bee-hunters, happiness-hunters, truth-hunters…Fine ladies in slippers, and moccasined squaws…Quakers in full drab…Sioux chiefs solemn as high priests.” Melville introduces into their company a vaudeville team of confidence men whom he likens to wandering rhapsodists—“the man in gray,” “the herb doctor,” “the Philosophical Intelligence Officer,” “the cosmopolitan.” Over the course of the novel they drum up forty-five conversations among the deceiving and the deceived on the great topic of confidence (why warranted, when abused, how acquired, why lost), and their swindling singspiele take the form of Socratic dialogues in comic dress.

Melville makes no attempt to drain the swamps of ambiguity, set the crooked straight, discover the lost gold mine of certain truth. Content with its setting on a ship of fools, his novel anticipates the teaching of the German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche who in 1873 observed that deception in all its forms (“flattery, lying and cheating, speaking behind the backs of others, keeping up appearances, living in borrowed finery, wearing masks, the drapery of convention, playacting for the benefit of others and oneself”) is what empowers the individual in his or her struggle against the superior forces of nature and the law.

The gentlemen songsters off on a spree aboard the Fidèle (its long, wide, covered deck built up on both sides to resemble “some Constantinople arcade or bazaar”) are contemporary with the wonders to behold in

P.T. Barnum’s justly famous museum of fantastic humbugs (Gen. Tom Thumb, twenty-five inches tall; the Feejee Mermaid, a.k.a. the head of a long-haired monkey bundled into the tail of a fish). The Life of P.T. Barnum, Written by Himself was published in 1855; retitled and updated several times over the next thirty years, the book was as fondly read as the Bible and established Barnum as one of the most beloved celebrities of his day and age.

By the turn of the twentieth century the marvels in Barnum’s museum were being transformed into merchandise on sale in the first generation of America’s opulent department-store arcades and bazaars. Consumer capitalism is the confidence game writ large, and between 1880 and 1930 it becomes the heart, soul, and primum mobile of America’s cultural, commercial, and intellectual enterprise. The Harvard Business School was founded in 1908 to teach the strategies of enticement, to inflate the operative values of blind, voracious consumption (pleasure, security, comfort, money the measure of all things) into general principles of existence, as immutable as the fixed stars, the multiplication tables, or the sea. The curriculum didn’t stress the means of production because by 1900 it was thought there were more than enough of these to supply everybody in the country with the goods required for the living of a contented life. But where was the fun in that? More importantly, where was the money to be made, and how build the yellow brick road to the dreams that men are made of?

L. Frank Baum, now chiefly remembered as author of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz but known to contemporaries as Chicago’s leading trimmer of department-store display windows, told his associates in 1898 to let the hats and shoes and furs “come alive” as if they were figures on a stage, to bring the “goods out in a blaze of glory,” invest them with color “that would delight the heart of an Oriental.” Baum commodifies the chorus to Shakespeare’s Henry V, who calls upon “a muse of fire that would ascend the brightest heaven of invention” to invest the groundlings in the Globe Theatre with the scene and sound of battle that “did affright the air at Agincourt”:

Piece out our imperfections with your thoughts.

Into a thousand parts divide one man,

And make imaginary puissance.

Think when we talk of horses that you see them.

So too the sales promotions that fabricate the retail merchant’s view of heaven, shape with the hand of romantic metaphor the willingness of the customers, gentles all, to see what isn’t there, to pay, and pay handsomely, for paper moons sailing over a bottomless sea of human hope and desire. Fortunately so. Were it otherwise, America’s colossal shopping malls and banks too big to fail would, like the “cloud-capp’d towers” and “solemn temples” on the enchanted islands of Shakespeare’s plays, melt into thin air, dissolve, fade, leave not a rack or an ATM behind.

No different from any other loyal American who loves to be fooled, I can’t remember a time in my life when I wasn’t drawn, mothlike, to the candles flickering in the wind of imaginary puissance. As a boy in San Francisco in the 1940s I found the American hero as noble knave and knight errant in comic books and Hollywood-movie palaces, in hard- and soft-boiled detective stories, with the troupe of confidence men performing in books by Mark Twain—Sawyer and Finn, but also the Duke and the Dauphin, the Yankee in King Arthur’s court, the jumping frog of Calaveras County. At boarding school I was introduced to Homer’s Odysseus, “man of twists and turns,” well schooled in the arts of dissimulation by the goddess of wisdom. In the years since I’ve yet to come across a confidence game as satisfactorily played as the heroic exile’s return to Ithaca—the setup in the disguise of feeble old age, the con protracted with the stringing of the great bow, the sting as unerring as the feathered death that did affright the air at Agincourt.

We have to distrust each other. It is our only defense against betrayal.

—Tennessee Williams, 1953Among the confidence men on the program at Yale College in the 1950s, top billing was reserved for F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Maj. Jay Gatsby, big-game hunter, World War I hero, collector of jewels, “chiefly rubies.” The narrator of Fitzgerald’s novel admits that on first listening to the major tell the story of his counterfeit life he was hard put to restrain his “incredulous laughter” because the threadbare masquerade was “leaking sawdust at every pore.” But on sober second thought that lasts no longer than a paragraph his doubts give way to “fascination…it was like skimming hastily through a dozen magazines.”

So also journalists and politicians skimming hastily through cue cards illuminating illusory talking points in a society abject in its adoration of graven images. My instruction on the methodology I owe to Daniel Patrick Moynihan, Democratic senator from New York in the years 1977 to 2001, effective legislator, eloquent orator, once-upon-a-time ambassador to the United Nations.

Somewhere in the mid-1980s we had been summoned to appear on the same radio news show, and in the green room awaiting our turns at the microphone, Moynihan ran through the long list of subjects on which he was presumed to be reliably informed—education, health care, foreign policy, highway construction, the multiplication of cancer cells. He didn’t bother to restrain his incredulous laughter. No senator could possibly know what he or she was expected to know, he said, but one was obliged to keep up appearances. Let the people understand how little their rulers know, and they might become frightened. When we talk of politics, he said, think of “a fourth-grade Christmas play. The little boy comes out onstage wearing a crown of paper stars and saying that he’s the north wind.” The thought pleased him, and when he was called into the studio knowing himself to be leaking sawdust at every pore, he paused in the doorway to strike a pose, adjust his expression from smiling to solemn, glance back over his shoulder to say, “Enter the north wind.”

Understand government as representative in the theatrical, not the constitutional, sense of the word and Moynihan’s observation was in keeping with that of Socrates instructing his student Glaucon in the use of “noble falsehood” as the stuff with which to bind society in self-preserving myth. Children must be taught to know what the rulers of the city would have them know in order to maintain the health and well-being of the body politic: “‘All of you in the city are brothers,’ we’ll say to them in telling our story, ‘but the god who made you mixed some gold into those who are adequately equipped to rule, because they are most valuable.’” Whether the story is true or false matters less than the children not forgetting their duty to believe it.

Fast-forward the lesson into the 1934 translation by Joseph Goebbels, minister of culture for Adolf Hitler’s Nazi Germany, and the noble falsehood becomes “propaganda…a necessary life function of the modern state,” the creative art that gives light and warmth to the body politic, and with it the power “to win and hold the heart of a people.”

Ask why the power failed in Germany’s Third Reich but not in Ronald Reagan’s America, and the answer, at least in part, is one proposed in the fourth century by Saint Augustine, a founding father of the Catholic Church: “Not everyone who says a false thing lies, if he believes or assumes what he says to be true…that man lies, who has one thing in his mind and utters another in words,” but a man may say a false thing “and yet not lie, if he thinks it to be so.”

Goebbels knew he was lying; Ronald Reagan did not. A movie actor rising like a paper moon in the make-believe Hollywood sky, the great communicator never doubted that all of it was so—America the beautiful as painted by Norman Rockwell, the home on the range made safe from Apaches by John Wayne, Jean Arthur, and Jimmy Stewart, the major motion picture produced by Cecil B. DeMille with music by Rodgers and Hammerstein, the theme park by Disney. To an electorate that in 1980 was sick of President Jimmy Carter’s niggling malaise, Reagan offered a happy return to an imaginary American past, a country “above all…where someone can always get rich.” During his eight years in office, playacting more for the benefit of others than for himself, Reagan was near perfect in his lines (“Honey, I forgot to duck”), sure of hitting his marks (on Omaha Beach, at the Berlin Wall), tipping his hat (straw, top, or dress uniform), snapping a sunny salute to a Girl Scout cookie or nuclear submarine. At ease with klieg light and sawdust, he preserved within himself the imperturbable calm of a public statue or a department-store window display.

The Saturday-matinee crowds loved him; so did the national news media. How could they not? Time magazine’s “sweet soul with firm if simple beliefs,” Reagan was as amiable a confidence man as Gatz, so obviously having such a good time on the White House vaudeville stage that it was easy to forgive his lapses of memory (the names of his own cabinet members, the whereabouts of Poland), his frequent flights of fancy (air pollution caused by too many trees, ketchup a nourishing vegetable).

Nor did it matter that 138 officials in the Reagan administration were investigated, indicted, or convicted on various charges of criminal fraud or misconduct, or that the Iran-Contra arms deal was comic farce played with a troupe of Iranian mullahs and a junta of Nicaraguan thugs depicted by President Reagan as “the moral equivalent of the founding fathers.” Congress never found out what happened to the money, the weapons, or the hostages. The questions were irrelevant because what mattered was the warmth of Reagan’s winning smile, his golden album of red, white, and blue metaphor instilling consumer confidence in an America that wasn’t there.

The Italian Charlatans, by Karel Dujardin, 1657.

The ancient Greeks were careful to distinguish between deceptions that served the public good and those engineered for private gain, the former set forth as works of art or the comforts of religion, the latter as brazen theft from a vast and inexhaustible supply of human vanity and greed. The Reagan administration was capable of both. The wandering rhapsodists aboard Melville’s Mississippi steamboat drew distinctions between a swindle that “dimples the cheek” and one “that curdles the blood,” but all of them held to the opinion that it’s a good thing—and speaks well for human nature—that men can be swindled. Their willingness to be fooled is a credit to their character, proof that their hearts and minds are not yet set in stone. Pride goeth before a fall, but trust goeth before a sham. The rule of thumb guided Ronald Reagan to the White House, confident in his conviction that “the difference between an American and any other kind of person is that an American lives in anticipation of the future because he knows it will be a great place.”

Which is the one true mark of American exceptionalism, the deal on the table of the democratic gamble with fortune, all present shuffling the currencies of contrived appearance. Encountering a stranger on a train (in an airport lounge, a motel parking lot, or a bar in Casablanca), who but an American envisions a prospective friend instead of a probable enemy? “There may not be an ‘American character,’” said the British essayist V.S. Pritchett, “but there is the emotion of being American…that feeling…of nostalgia for some undetermined future when man will have improved himself beyond recognition and when all will be well.” Pilgrims outward or homeward bound on yellow brick roads of their own invention, Americans tell each other travelers’ tales—the story so far, youth and early sorrow, sequence of exits and entrances, last divorce and next marriage, point of financial departure, estimated time of spiritual arrival, the bad news noted and accounted for, the good news still to come. Think, when we talk of horses, that you see them.