Weaseling out of things is important to learn. It’s what separates us from the animals—except the weasel.

—The Simpsons, 1993In the Mouth of a Whale

Herman Melville and the watery beast.

That night, in the midwatch, when the old man—as his wont at intervals—stepped forth from the scuttle in which he leaned and went to his pivot hole, he suddenly thrust out his face fiercely, snuffing up the sea air as a sagacious ship’s dog will in drawing nigh to some barbarous isle. He declared that a whale must be near.

Soon that peculiar odor, sometimes to a great distance given forth by the living sperm whale, was palpable to all the watch; nor was any mariner surprised when, after inspecting the compass, and then the dog vane, and then ascertaining the precise bearing of the odor as nearly as possible, Ahab rapidly ordered the ship’s course to be slightly altered and the sail to be shortened.

The acute policy dictating these movements was sufficiently vindicated at daybreak by the sight of a long sleek on the sea directly and lengthwise ahead, smooth as oil, and resembling in the pleated watery wrinkles bordering it the polished metallic-like marks of some swift tide rip at the mouth of a deep, rapid stream.

“Man the mastheads! Call all hands!”

Thundering with the butts of three clubbed handspikes on the forecastle deck, Daggoo roused the sleepers with such judgment claps that they seemed to exhale from the scuttle, so instantaneously did they appear with their clothes in their hands.

“What d’ye see?” cried Ahab, flattening his face to the sky.

“Nothing, nothing, sir!” was the sound hailing down in reply.

“T’gallant sails!—stunsails! Alow and aloft, and on both sides!”

All sail being set, he now cast loose the lifeline, reserved for swaying him to the main royal masthead; and in a few moments they were hoisting him thither, when, while but two-thirds of the way aloft and while peering ahead through the horizontal vacancy between the main topsail and topgallant sail, he raised a gull-like cry in the air, “There she blows!—there she blows! A hump like a snow hill! It is Moby Dick!”

Fired by the cry which seemed simultaneously taken up by the three lookouts, the men on deck rushed to the rigging to behold the famous whale they had so long been pursuing. Ahab had now gained his final perch, some feet above the other lookouts, Tashtego standing just beneath him on the cap of the topgallant mast, so that the Indian’s head was almost on a level with Ahab’s heel. From this height the whale was now seen some mile or so ahead, at every roll of the sea revealing his high, sparkling hump and regularly jetting his silent spout into the air. To the credulous mariners it seemed the same silent spout they had so long ago beheld in the moonlit Atlantic and Indian oceans.

“And did none of ye see it before?” cried Ahab, hailing the perched men all around him.

“I saw him almost that same instant that

Captain Ahab did, and I cried out,” said Tashtego.

“Not the same instant; not the same—no, the doubloon is mine, Fate reserved the doubloon for me. I only; none of ye could have raised the White Whale first. There she blows! There she blows!—there she blows! There again!—there again!” he cried, in long-drawn, lingering, methodic tones, attuned to the gradual prolongings of the whale’s visible jets. “He’s going to sound! In stunsails! Down topgallant sails! Stand by three boats. Mr. Starbuck, remember, stay onboard, and keep the ship. Helm there! Luff, luff a point! So; steady, man, steady! There go flukes! No, no; only black water! All ready the boats there? Stand by, stand by! Lower me, Mr. Starbuck; lower, lower—quick, quicker!” and he slid through the air to the deck.

“He is heading straight to leeward, sir,” cried Stubb, “right away from us; cannot have seen the ship yet.”

“Be dumb, man! Stand by the braces! Hard down the helm!—brace up! Shiver her!—shiver her! So; well that! Boats, boats!”

Soon all the boats but Starbuck’s were dropped; all the boat sails set—all the paddles plying; with rippling swiftness, shooting to leeward; and Ahab heading the onset. A pale death glimmer lit up Fedallah’s sunken eyes, a hideous motion gnawed his mouth.

Like noiseless nautilus shells, their light prows sped through the sea, but only slowly they neared the foe. As they neared him, the ocean grew still more smooth; seemed drawing a carpet over its waves; seemed a noon meadow, so serenely it spread. At length the breathless hunter came so nigh his seemingly unsuspecting prey that his entire dazzling hump was distinctly visible, sliding along the sea as if an isolated thing and continually set in a revolving ring of finest, fleecy, greenish foam. He saw the vast, involved wrinkles of the slightly projecting head beyond. Before it, far out on the soft Turkish-rugged waters, went the glistening white shadow from his broad, milky forehead, a musical rippling playfully accompanying the shade; and behind, the blue waters interchangeably flowed over into the moving valley of his steady wake; and on either hand bright bubbles arose and danced by his side. But these were broken again by the light toes of hundreds of gay fowl softly feathering the sea, alternate with their fitful flight; and like to some flagstaff rising from the painted hull of an argosy, the tall but shattered pole of a recent lance projected from the white whale’s back; and at intervals one of the cloud of soft-toed fowls hovering and to and fro skimming like a canopy over the fish, silently perched and rocked on this pole, the long tail feathers streaming like pennons.

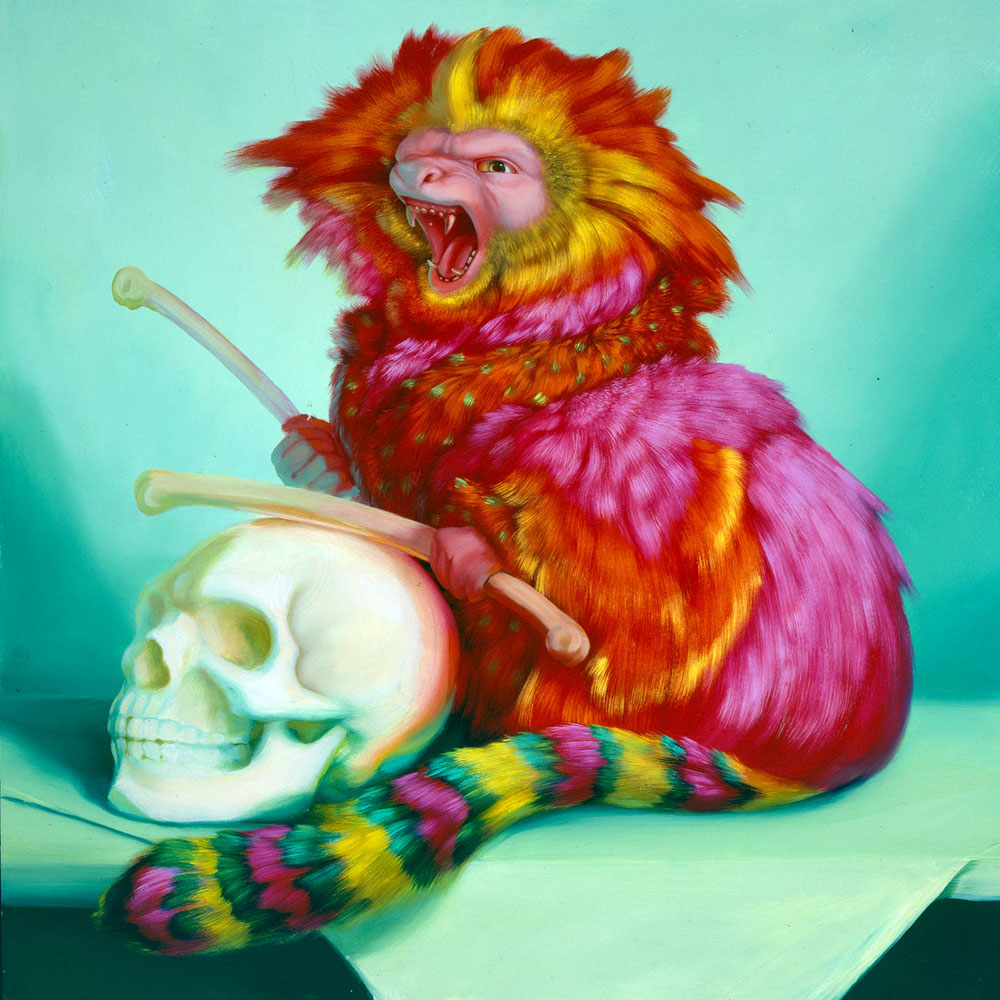

Field Guide to Contemporary Primates: Muzak’s Macaque (mono malliensis), by Laurie Hogin, 2004. Oil on panel, 20" x 20". © Laurie Hogin, courtesy of the artist and Littlejohn Contemporary, New York.

A gentle joyousness—a mighty mildness of repose in swiftness, invested the gliding whale. Not the white bull Jupiter swimming away with ravished Europa clinging to his graceful horns; his lovely, leering eyes sideways intent upon the maid; with smooth bewitching fleetness, rippling straight for the nuptial bower in Crete; not Jove—not that great majesty supreme!—did surpass the glorified White Whale as he so divinely swam.

On each soft side—coincident with the parted swell, that but once leaving him, then flowed so wide away—on each bright side, the whale shed off enticings. No wonder there had been some among the hunters who, namelessly transported and allured by all this serenity, had ventured to assail it but had fatally found that quietude but the vesture of tornadoes. Yet calm, enticing calm, oh, whale! Thou glidest on, to all who for the first time eye thee, no matter how many in that same way thou may’st have bejuggled and destroyed before.

And thus, through the serene tranquilities of the tropical sea, among waves whose hand clappings were suspended by exceeding rapture, Moby Dick moved on, still withholding from sight the full terrors of his submerged trunk, entirely hiding the wrenched hideousness of his jaw. But soon the fore part of him slowly rose from the water; for an instant his whole marbleized body formed a high arch, like Virginia’s Natural Bridge, and warningly waving his bannered flukes in the air, the grand god revealed himself, sounded, and went out of sight. Hoveringly halting and dipping on the wing, the white seafowls longingly lingered over the agitated pool that he left.

With oars apeak and paddles down, the sheets of their sails adrift, the three boats now stilly floated, awaiting Moby Dick’s reappearance.

“An hour,” said Ahab, standing rooted in his boat’s stern, and he gazed beyond the whale’s place toward the dim blue spaces and wide wooing vacancies to leeward. It was only an instant, for again his eyes seemed whirling round in his head as he swept the watery circle. The breeze now freshened; the sea began to swell.

“The birds!—the birds!” cried Tashtego.

In long Indian file, as when herons take wing, the white birds were now all flying toward Ahab’s boat, and when within a few yards, began fluttering over the water there, wheeling round and round, with joyous, expectant cries. Their vision was keener than man’s; Ahab could discover no sign in the sea. But suddenly as he peered down and down into its depths, he profoundly saw a white living spot no bigger than a white weasel, with wonderful celerity uprising, and magnifying as it rose, till it turned, and then there were plainly revealed two long crooked rows of white, glistening teeth, floating up from the undiscoverable bottom. It was Moby Dick’s open mouth and scrolled jaw; his vast, shadowed bulk still half blending with the blue of the sea. The glittering mouth yawned beneath the boat like an open-doored marble tomb, and giving one sidelong sweep with his steering oar, Ahab whirled the craft aside from this tremendous apparition. Then, calling upon Fedallah to change places with him, went forward to the bows, and seizing Perth’s harpoon, commanded his crew to grasp their oars and stand by to stern.

Now, by reason of this timely spinning round the boat upon its axis, its bow, by anticipation, was made to face the whale’s head while yet underwater. But as if perceiving this stratagem, Moby Dick, with that malicious intelligence ascribed to him, sidelingly transplanted himself, at it were, in an instant, shooting his pleated head lengthwise beneath the boat.

Through and through; through every plank and each rib, it thrilled for an instant, the whale obliquely lying on his back, in the manner of a biting shark, slowly and feelingly taking its bows full within his mouth, so that the long, narrow, scrolled lower jaw curled high up into the open air, and one of the teeth caught in a row lock. The bluish pearl-white of the inside of the jaw was within six inches of Ahab’s head, and reached higher than that. In this attitude the White Whale now shook the slight cedar as a mildly cruel cat her mouse. With unastonished eyes, Fedallah gazed and crossed his arms, but the tiger-yellow crew were tumbling over each other’s heads to gain the uttermost stern.

There be beasts that, at a year old, observe more, and pursue that which is for their good more prudently, than a child can do at ten.

—Thomas Hobbes, 1651And now, while both elastic gunwales were springing in and out, as the whale dallied with the doomed craft in this devilish way, and from his body being submerged beneath the boat, he could not be darted at from the bows, for the bows were almost inside of him, as it were; and while the other boats involuntarily paused, as before a quick crisis impossible to withstand, then it was that monomaniac Ahab, furious with this tantalizing vicinity of his foe, which placed him all alive and helpless in the very jaws he hated; frenzied with all this, he seized the long bone with his naked hands and wildly strove to wrench it from its grip. As now he thus vainly strove, the jaw slipped from him; the frail gunwales bent in, collapsed, and snapped, as both jaws, like an enormous shears, sliding farther aft, bit the craft completely in twain, and locked themselves fast again in the sea, midway between the two floating wrecks. These floated aside, the broken ends drooping, the crew at the stern wreck clinging to the gunwales and striving to hold fast to the oars to lash them across.

At that preluding moment, ere the boat was yet snapped, Ahab, the first to perceive the whale’s intent, by the crafty upraising of his head, a movement that loosed his hold for the time, at that moment his hand had made one final effort to push the boat out of the bite. But only slipping farther into the whale’s mouth and tilting over sideways as it slipped, the boat had shaken off his hold on the jaw; spilled him out of it, as he leaned to the push; and so he fell flat-faced upon the sea.

Ripplingly withdrawing from his prey, Moby Dick now lay at a little distance, vertically thrusting his oblong white head up and down in the billows, and at the same time slowly revolving his whole spindled body so that when his vast wrinkled forehead rose—some twenty or more feet out of the water—the now rising swells, with all their confluent waves, dazzling broke against it, vindictively tossing their shivered spray still higher into the air. So, in a gale, the but half-baffled Channel billows only recoil from the base of the Eddystone, triumphantly to overleap its summit with their scud.

But soon resuming his horizontal attitude, Moby Dick swam swiftly round and round the wrecked crew, sideways churning the water in his vengeful wake as if lashing himself up to still another and more deadly assault. The sight of the splintered boat seemed to madden him, as the blood of grapes and mulberries cast before Antiochus’ elephants in the book of Maccabees. Meanwhile Ahab half-smothered in the foam of the whale’s insolent tail and too much of a cripple to swim—though he could still keep afloat, even in the heart of such a whirlpool as that—helpless Ahab’s head was seen, like a tossed bubble which the least chance shock might burst. From the boat’s fragmentary stern, Fedallah incuriously and mildly eyed him; the clinging crew at the other drifting end could not succor him; more than enough was it for them to look to themselves. For so revolvingly appalling was the White Whale’s aspect and so planetarily swift the ever-contracting circles he made, that he seemed horizontally swooping upon them. And though the other boats, unharmed, still hovered hard by, still they dared not pull into the eddy to strike, lest that should be the signal for the instant destruction of the jeopardized castaways, Ahab and all, nor in that case could they themselves hope to escape. With straining eyes, then, they remained on the outer edge of the direful zone, whose center had now become the old man’s head.

Meantime, from the beginning all this had been descried from the ship’s mastheads, and squaring her yards, she had borne down upon the scene, and was now so nigh that Ahab in the water hailed her—“Sail on the”—but that moment a breaking sea dashed on him from Moby Dick and whelmed him for the time. But struggling out of it again, and chancing to rise on a towering crest, he shouted, “Sail on the whale!—drive him off!”

Wing of a Blue Roller, by Albrecht Dürer, 1512. Albertina Museum, Vienna.

The ’s prows were pointed, and breaking up the charmed circle, she effectually parted the White Whale from his victim. As he sullenly swam off, the boats flew to the rescue.

Dragged into Stubb’s boat with bloodshot, blinded eyes, the white brine caking in his wrinkles, the long tension of Ahab’s bodily strength did crack, and helplessly he yielded to his body’s doom: for a time, lying all crushed in the bottom of Stubb’s boat, like one trodden underfoot of herds of elephants. Far inland, nameless wails came from him, as desolate sounds from out ravines.

But this intensity of his physical prostration did but so much the more abbreviate it. In an instant’s compass, great hearts sometimes condense to one deep pang, the sum total of those shallow pains kindly diffused through feebler men’s whole lives. And so, such hearts, though summary in each one suffering; still, if the gods decree it, in their lifetime aggregate a whole age of woe, wholly made up of instantaneous intensities, for even in their pointless centers, those noble natures contain the entire circumferences of inferior souls.

“The harpoon,” said Ahab, halfway rising and draggingly leaning on one bended arm, “is it safe?”

“Aye, sir, for it was not darted; this is it,” said Stubb, showing it.

“Lay it before me—any missing men?”

“One, two, three, four, five; there were five oars, sir, and here are five men.”

“That’s good. Help me, man; I wish to stand. So, so, I see him! There! There! Going to leeward still; what a leaping spout! Hands off from me! The eternal sap runs up in Ahab’s bones again! Set the sail; out oars; the helm!”

Herman Melville

From Moby Dick. After writing two successful adventure novels based on his experiences as a sailor, Typee and Omoo, Melville published the more allegorical Mardi in 1849; it did not sell well. By May 1850, he wrote to author and attorney Richard Henry Dana Jr. to report that he was halfway done with his whaling book, and that summer he met Nathaniel Hawthorne, to whom he dedicated Moby Dick, published in 1851. When Melville died at the age of seventy-two in 1891, one obituary noted that “even his own generation has long thought him dead.”