Democracy is the menopause of Western society, the grand climacteric of the body social. Fascism is its middle-aged lust.

—Jean Baudrillard, 1987Sweet-Smelling Lies

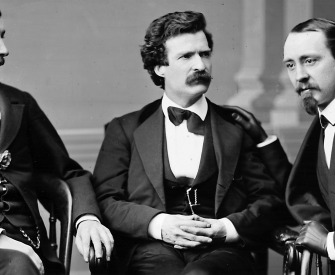

We are discreet sheep, says Mark Twain.

There are certain sweet-smelling, sugarcoated lies current in the world which all politic men have apparently tacitly conspired together to support and perpetuate. One of these is that there is such a thing in the world as independence: independence of thought, independence of opinion, independence of action.

Another is that the world loves to see independence—admires it, applauds it. Another is that there is such a thing in the world as toleration—in religion, in politics, and such matters; and with it trains that already mentioned auxiliary lie that toleration is admired and applauded. Out of these trunk lies spring many branch ones: to wit, the lie that not all men are slaves; the lie that men are glad when other men succeed; glad when they prosper; glad to see them reach lofty heights; sorry to see them fall again. And yet other branch lies: to wit, that there is heroism in man; that he is not mainly made up of malice and treachery; that he is sometimes not a coward; that there is something about him that ought to be perpetuated—in heaven, or hell, or somewhere. And these other branch lies, to wit: that conscience, man’s moral medicine chest, is not only created by the Creator but is put into man ready charged with the right and only true and authentic correctives of conduct—and the duplicate chest, with the selfsame correctives, unchanged, unmodified, distributed to all nations and all epochs. And yet one other branch lie: to wit, that I am I, and you are you; that we are units, individuals, and have natures of our own, instead of being the tail end of a tapeworm eternity of ancestors extending in linked procession back and back and back to our source in the monkeys, with this so-called individuality of ours a decayed and rancid mush of inherited instincts and teachings derived, atom by atom, stench by stench, from the entire line of that sorry column, and not so much new and original matter in it as you could balance on a needle point and examine under a microscope. This makes well-nigh fantastic the suggestion that there can be such a thing as a personal, original, and responsible nature in a man separable from that in him which is not original, and findable in such quantity as to enable the observer to say, This is a man, not a procession.

Consider the first-mentioned lie: that there is such a thing in the world as independence; that it exists in individuals; that it exists in bodies of men. Surely if anything is proven, by whole oceans and continents of evidence, it is that the quality of independence was almost wholly left out of the human race. The scattering exceptions to the rule only emphasize it, light it up, make it glare. We are discreet sheep; we wait to see how the drove is going, and then go with the drove. We have two opinions: one private, which we are afraid to express; and another one—the one we use—which we force ourselves to wear to please Mrs. Grundy, until habit makes us comfortable in it, and the custom of defending it presently makes us love it, adore it, and forget how pitifully we came by it. Look at it in politics. Look at the candidates whom we loathe one year and are afraid to vote against the next; whom we cover with unimaginable filth one year and fall down on the public platform and worship the next—and keep on doing it until the habitual shutting of our eyes to last year’s evidence brings us presently to a sincere and stupid belief in this year’s. Look at the tyranny of party—at what is called party allegiance, party loyalty—a snare invented by designing men for selfish purposes—and which turns voters into chattels, slaves, rabbits, and all the while their masters and they themselves are shouting rubbish about liberty, independence, freedom of opinion, freedom of speech, honestly unconscious of the fantastic contradiction; and forgetting or ignoring that their fathers and the churches shouted the same blasphemies a generation earlier when they were closing their doors against the hunted slave, beating his handful of humane defenders with Bible texts and billies, and pocketing the insults and licking the shoes of his Southern master.

If we would learn what the human race really is at bottom, we need only observe it in election times. A Hartford clergyman met me in the street and spoke of a new nominee—denounced the nomination, in strong, earnest words—words that were refreshing for their independence, their manliness. He said, “I ought to be proud, perhaps, for this nominee is a relative of mine. On the contrary, I am humiliated and disgusted, for I know him intimately—familiarly—and I know that he is an unscrupulous scoundrel, and always has been.” You should have seen this clergyman preside at a political meeting forty days later, and urge, and plead, and gush—and you should have heard him paint the character of this same nominee. You would have supposed he was describing the Cid, and Greatheart, and Sir Galahad, and Bayard the Spotless all rolled into one. Was he sincere? Yes—by that time; and therein lies the pathos of it all, the hopelessness of it all. It shows at what trivial cost of effort a man can teach himself to lie, and learn to believe it, when he perceives, by the general drift, that that is the popular thing to do. Does he believe his lie yet? Oh, probably not; he has no further use for it. It was but a passing incident; he spared to it the moment that was its due, then hastened back to the serious business of his life.

Mark Twain

From The Autobiography of Mark Twain. Born Samuel Clemens, Twain trained as a pilot on the Mississippi River in 1857 at the age of twenty-one. His steamboat career ended four years later with the outbreak of the Civil War. Twain took his pen name from the riverboat expression for a depth of twelve feet, using the name for the first time in 1863 while working as a reporter in Nevada. His notes for this book came from interviews with a biographer, who described spending mornings in Twain’s bedroom, where Twain gave dictation “clad in a handsome dressing gown, propped against great snowy pillows.”