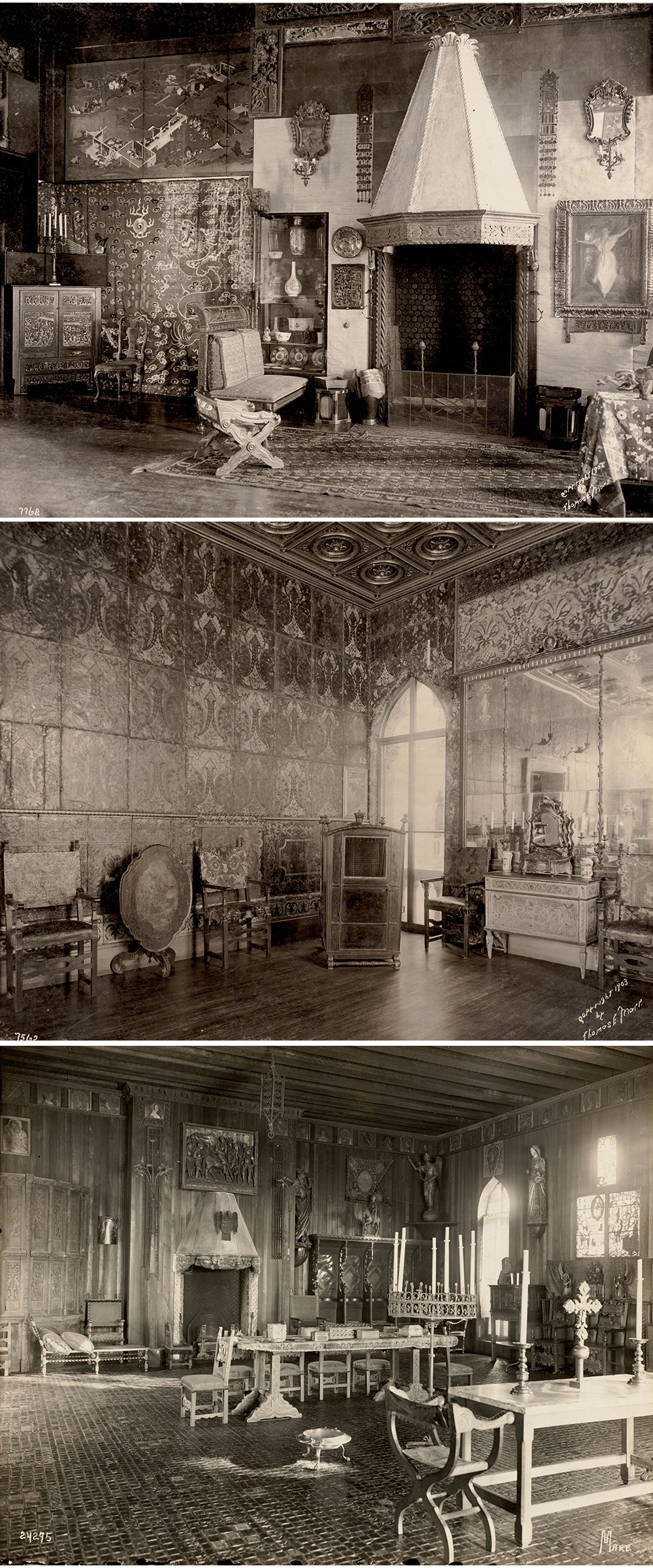

Titian room at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, 1903. Photograph by Thomas E. Marr. Digital Commonwealth, Boston Public Library.

Constantly under the pressure of public scrutiny, Isabella Stewart Gardner shrouded her museum project in secrecy from the outset. Her architect Willard T. Sears recalled that at their very first encounter in 1896, she instructed him to “keep the matter secret from everybody.” Construction and installation unfolded under similar terms. Gardner borrowed some fittings from her existing residences—like the Venetian fireplace flanked by heraldic textiles in Green Hill’s Venetian Music Room that she repurposed for Fenway Court. Because she worked out her designs and installations by trial and error, she must have known that she was not likely to receive positive treatment in the press until the museum was complete. Yet the silence prompted wild speculation by journalists, who characterized the museum as Gardner’s “mysterious building.” One article claimed that she had bought Florence’s grandest palace, the Palazzo Pitti, shipped it to America, and was reconstructing the behemoth brick by brick in Boston. weird wall shuts mrs. “jack” gardner’s palace in from the world and causes speculation among the curious who watch it growing, ran another headline in June 1901. Instead of celebrating the new building, the newspaper dismissed it as the “Whim of a Woman,” a phrase lifted from the headline of an 1899 profile on Gardner in the New York Journal and Advertiser. The gossipy tone and dismissive language of this coverage attest to the precarious status of a newly widowed woman in a male environment whose actions often fell outside the boundaries of society’s accepted norms.

As a visionary curator rather than a trained architect, Gardner’s conviction of taste often collided with the prosaic realities of construction, challenging her relationship with Sears. Photographs reveal that she supervised the installation of architectural salvage, climbed up ladders, and directed activities onsite; this went on to such an extent that Sears advised her to take out accident insurance (Gardner declined). She changed the heights of windows, swapped one color of bricks for another, insisted on wooden beams when steel was the norm, relocated heating ducts, and even “stopped the masons Saturday afternoon…had them take down what they had built and build a portion of it at a lower level.” The frustration of her architect shines through in his detailed diary entries, which biographers have often drawn from to paint her in a negative light as the proverbial “exasperating woman.” Their sexism is manifest. If Gardner had been a man, she would have been characterized by the same biographers as the brilliant and hard-nosed business titan who stood by his beliefs in the face of all challenges. As it was, like most first-time clients working with an architect, she did not always understand the practical implications of her decisions until confronted, and then responded, naturally, with vexation. More to the point, she learned from mistakes and adapted quickly, ultimately accepting some of Sears’ suggestions and never losing her focus on fundamental elements, such as her battle—ultimately successful—for a glass roof enclosing the courtyard, to make her plan for the garden a reality.

During construction, Gardner frequently came into contact with men of lower classes, and she was a familiar presence among the carpenters, bricklayers, and stonemasons. Despite attempts to paint Gardner as “of the people” in stories about her taking lunch with the workers, their recorded interactions were often fraught. To cite two examples, she ordered a team to remove scaffoldings against the architect’s wishes, and she called the foreman a “thief.” Since Gardner did not record any of her own thoughts on these matters and newspaper reporting cannot be trusted, it remains difficult to know the truth.

Names of the men who built the Gardner Museum survive in Isabella’s register of “Contractors Used During Construction,” even if little is known of their specific personal circumstances. Many were Italian and Irish immigrants, although at least one hailed from Japan. They all worked long hours for little pay. Massachusetts adopted a nine-hour workday in 1891, optionally reduced to eight hours in 1899, but only if the majority of voters of the city in question accepted the change. The state, while first to do so, did not enact a minimum wage until 1912, and then it was only for women and children. Bricklayers, for example, made $3.60 per day on a project where changing the height of a single window cost $300 to $400. Gardner encountered these realities head-on in 1901 when carpenters in Boston went on strike for an eight-hour workday without a reduction in wages. According to newspapers, she received their delegation at home to listen to their grievances. She also met with the building laborers’ union, who claimed a middleman was pocketing 50 cents of their $2-per-day wages. Whether she was interested in keeping the status quo or in advancing their cause remains unclear.

Among the site’s workers, Teobaldo Travi, nicknamed “Bolgi,” stands out. Born in Milan, he immigrated to the United States and, by 1889, was a resident of Dorchester, Massachusetts. An employee of one of her contractors, Gardner chose him to oversee the transport of building materials and historical elements, such as the stylobate lion (a column base from Italy, dating to about 1200) that anchors a corner of the courtyard colonnade. Gardner admired his careful work and later hired him on a monthly salary, first as a watchman and later as the museum’s majordomo. In that role, he ran Gardner’s household and oversaw visits to the museum, often in an elaborate uniform designed by Joseph Lindon Smith. In this guise he wore a Napoleonic hat and carried a staff. Bolgi cut a striking figure. One newspaper eventually published a caricature captioned “The Veronese policeman,” satirizing his role as the guardian of Gardner’s Renaissance masterpieces. He worked for the museum for forty-one years before retiring in 1940.

In the midst of the construction, Gardner confirmed the status of her museum as a public institution. In December 1900 she obtained a charter and incorporated the museum as the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in the Fenway “for the purpose of art education, especially by the public exhibition of works of art.” Repositioning her private collection to work for the public benefit was a task long in the making, and Gardner had already begun to purchase entire categories of objects, perhaps to fill in perceived gaps in the visitor experience. For instance, in 1897 she acquired most of her Christian reliquaries as a gift from her husband, Jack, and later installed them together in a single case in the Long Gallery. In 1902 she acquired most of the museum’s Old Master drawings at a single auction in London, including sheets by Filippino Lippi, Michelangelo, Raphael, and others. She installed most of them together in the Short Gallery in a single row of cases.

Installation lasted almost two years, nearly as long as it had taken to build the museum. In December 1901 Isabella moved into the fourth-floor apartment at Fenway Court and celebrated her first Christmas Midnight Mass in the museum’s chapel. Compared to the substantial house on Beacon Street, Gardner’s modest new quarters allowed her to reduce household expenses, preserve more money for her collection, and focus attention on the museum. She sold 152 Beacon Street in 1902 and made her new living quarters as much like her former home as possible by salvaging its doors, fireplaces, and lighting fixtures. As a wealthy woman, she managed a household staff with a housekeeper, maid, and cook, but many of their names and stories are lost to history. Margaret Lamar is an exception. She was Isabella’s loyal housekeeper, who had emigrated from Ireland in 1870. She began working for the Gardners early in their marriage and moved with Isabella from Beacon Street to Fenway Court. Isabella stipulated that Margaret be allowed to stay in her living quarters at the museum if she outlived her. Margaret died in 1928, four years after Isabella, and was buried in Saint Joseph’s Cemetery in West Roxbury (the museum paid for the funerary expenses).

As Isabella settled into domestic life in her museum—with her pet terriers Kitty Wink and Patty Boy—artworks and furniture continued to arrive, both from abroad and from her existing installations at Beacon Street and Green Hill, which included everything from Japanese screens to Venetian furniture. By January 1902 the galleries were complete enough to allow in a journalist, who finally brought her some positive press: inside mrs. j.l. gardner’s splendid treasure house. Gardner lavished attention on each room, transforming bare walls into textured backdrops for paintings, sculpture, and furniture and evoking richly furnished domestic spaces. She chose paint as meticulously as she curated paintings. Insisting on a specific blue, she had instructed Berenson to source “a piece of paper [with] the blue color that [the Florentine art dealer] Bardini has on his walls. I want the exact tint.”

She dispensed with explanatory labels or texts, rejecting the encyclopedic museum model that sought to teach the visiting public about how art fit into neatly divided periods and places. Instead, she mounted installations that create visual relationships between works of art, which in turn reveal thematic, aesthetic, and historical relationships that transcend boundaries of time, place, and style. Few notes survive, with the exception of a list of paintings for the Gothic Room, a space closed to the public during her lifetime, and a sketch she made of the Dutch Room. These remnants suggest a process of trial, error, and experimentation, also borne out in the early photographs of individual rooms by the local photographer Thomas E. Marr. His black-and-white pictures not only provide the earliest official images of her process but also attest to the importance to her of its outcome and her determination to record and preserve her curatorial vision as much as the acquisition of individual works of art.

Several rooms served specific purposes. Gardner situated a concert hall adjacent to the main courtyard, signaling the importance of music, which had been a lifelong passion. At the far end of the room rose the stage, lined with Flemish tapestries and decorated with a copy of the relief sculptures by Renaissance master Luca della Robbia for the organ of Florence Cathedral. Concerned as much with the hall’s performance as its appearance, Gardner paused construction to bring in musicians from the Boston Symphony Orchestra to test its acoustic properties. Seating for one hundred to one hundred and fifty audience members extended back to the door. And at either side of the entrance, galleries served as waiting rooms: the Yellow Room for the men and the Blue Room for the women. In the former, cases lining the walls displayed Isabella’s correspondence with famed composers and performers, including Johannes Brahms and Franz Liszt, and plaster casts of Beethoven’s face and violinist-composer Charles Martin Loeffler’s hand. Above hung a portrait of Loeffler by John Singer Sargent and another of the ballerina Joséphine Gaujelin by Edgar Degas (added one year after opening, in 1904).

In the middle of winter, on January 1, 1903, Gardner opened her museum to the public. Between three hundred and four hundred guests from the cream of Boston society braved the cold and traveled out to the city’s periphery—an area noted for being a landfill—to take part in the event. Gardner greeted them like a Renaissance sovereign. As the Boston Symphony Orchestra played the overture to Mozart’s Magic Flute in the Music Room, she opened its doors to reveal the glass-roofed courtyard filled with flowers and green foliage, a defiant gesture in the middle of the Boston winter. The artworks glistened to the light of a thousand lit candles. Friends were overwhelmed. William James, philosopher and brother of the writer Henry, exclaimed that it was “quite in the line of a Gospel miracle!” His brother later teased Gardner, “Is the pope going to sell you one of the rooms of the Vatican?” In the aftermath of the opening, Charles Eliot Norton described the heady atmosphere: “Palace and gallery (there is no other word for it) are such an exhibition of the genius of a woman of wealth as never seen before. The building, of which she is the sole architect, is admirably designed. I know of no private collection in Europe which compares with this in the uniform level of the works it contains.”

According to legend, only Edith Wharton was underwhelmed by the evening. She disparaged Isabella’s choice of refreshments—champagne and doughnuts—as fit for a provincial French train station. Yet no one else agreed. The opening of Fenway Court, as the museum was called during her lifetime, was a major event for the city of Boston and for Gardner herself. While Isabella Stewart Gardner was certainly a notable person before the opening of her museum, the creation of the exceptional institution launched her into a spotlight that endures to this day.

Excerpted from Isabella Stewart Gardner: A Life by Nathaniel Silver and Diana Seave Greenwald. Copyright © 2022 Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston. Reprinted by permission of the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston, and distributed by Princeton University Press, Princeton and Oxford.