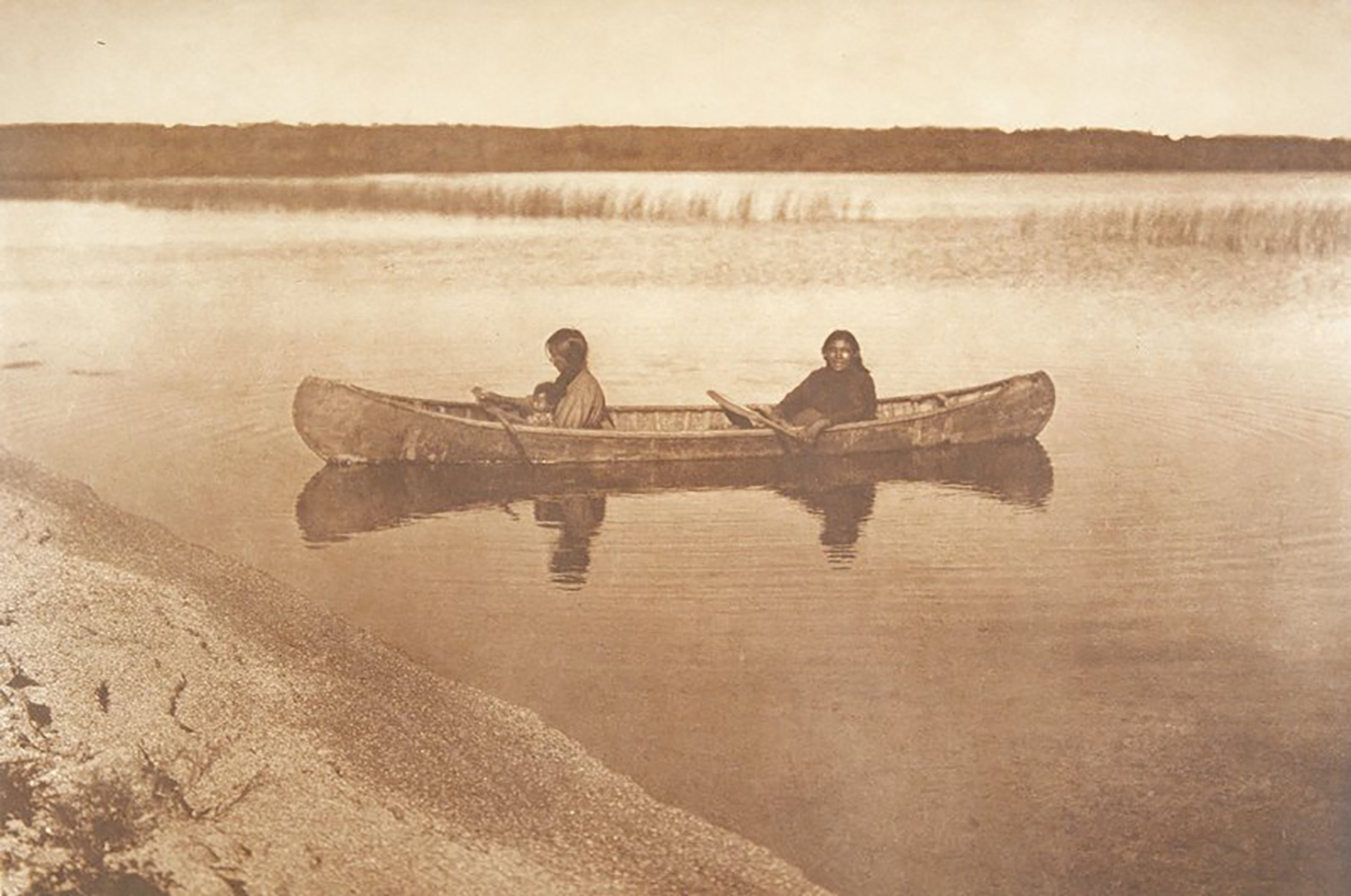

A Cree Canoe on Lac les Isles, by Edward S. Curtis, 1926. Minneapolis Institute of Art, gift of Joe Lange.

As tentative peace between indigenous Americans and Europeans in the eighteenth century created conditions for an expanding fur trade in North America, demand for fur exploded in Europe. As a luxury—like coffee, tulips, and spices—the more expensive fur got, the more people wanted it. As prices doubled in both the London and the Paris markets over the eighteenth century, the number of furs crossing the Atlantic quadrupled. From just two ports on Hudson’s Bay, furs shipped each season increased from two thousand pelts in 1710 to fifty thousand pelts by 1740. Combined with the less recorded but still vast trade from the smaller French companies that operated around the Great Lakes, somewhere between 400,000 and one million animal skins left North America each year during most of the eighteenth century. The trade would eventually deplete the supply of animals, but only after another century of steady expansion.

A dense human network evolved to hunt, kill, package, ship, and make clothing from millions of beavers, martens, and minks. Brave or desperate young men left home to live among Native American people who didn’t speak French or English. They left from docks along the St. Lawrence or from Hudson’s Bay in small canoes filled with Crees, Ojibwes, or Hurons. From the moment they arrived at Hudson’s Bay, where large Cree settlements encircled the trading posts, or at the edge of Lake Ontario, where Ojibwe and Odawa villages lined the shore, European men entered a new world. Native people knew that landscape like they knew their own skins, and the fur trade made that knowledge valuable. A young Hudson’s Bay Company officer admitted that “we would have starved if we did not send out those Indians that keep constant attendance to shoot geese and hares.”

The mixed-descent families made in a Native world were a key component of the global fur trade. Every winter produced a harvest of furs, new relationships, and babies. Every spring European men filled their canoes with furs and hides, dried and pressed into ninety-pound packs. Their local partners loaded household goods and children to move to summer villages, now located near trading depots like Michilimackinac, where Lakes Huron and Michigan come together. In 1763 a British census estimated that more than fifty thousand Native people lived by hunting and growing crops around the Great Lakes. That population overwhelmed the perhaps two thousand European men who lived among them.

Marrying and bearing children together didn’t end violence between indigenous and European Americans. In the 1750s, when colonial wars replaced Indian peace, the means to survive the violence became personal. Indian women, making choices that benefited their families and nations, took risks to weave new families from strangers arriving in their villages and from fur traders who wanted clan business.

Étienne Waddens was one of them. A well-educated Protestant from Berne, Switzerland, he had been hired by the British to fight the French in North America. He arrived in Canada in 1757 at the age of nineteen, as the Seven Years’ War was raking across Europe, North America, and the Caribbean. Like many other soldiers, Étienne left the army but chose not to return to Switzerland, which was itself mired in war and religious unrest. Abandoning his past and his Protestant religion, Waddens stayed in Canada as a merchant and a Catholic. By 1761 he felt settled enough to marry a French woman named Marie-Joseph Deguire. They bought property in Montreal and baptized three children in the Catholic Church.

To support his family, Waddens turned to the fur trade. He convinced some Montreal merchants to help him outfit a small contingent of young French men who would travel into Indian Country to trade for furs. The merchants would provide a year’s worth of trade goods, supplies, and a canoe to take them into fur country. To repay that loan, the traders had to bring back enough furs to satisfy their sponsors. To protect that investment, Étienne Waddens paddled with them down the St. Lawrence River in 1766, intending to spend the winter around the Great Lakes.

That venture succeeded. By 1770 Waddens had enough money to form his own small partnership, one of many trading outfits that were stealing business away from the Hudson’s Bay Company. These smaller fur enterprises—staffed by men willing to travel to the interior and bring trade goods, including guns, ammunition, and alcohol, to Indian settlements—made useful allies for Native people. With advice from tribal leaders, fur traders built a series of inland entrepôts like Michilimackinac, Grand Portage, and Rainy Lake. This trade, run almost exclusively by Native hunters and French Canadians, rapidly spread north and west after the Treaty of Paris in 1763. As winter trading posts extended farther north, the traders competed directly with the Hudson’s Bay Company.

Literate and practical, Waddens rose quickly in that sector of the trade. He had the advantages of being Swiss and not English, and speaking both French and English. In 1772 he received a license to trade at Grand Portage, the connecting point between far northern winter posts and the Great Lakes and St. Lawrence transportation routes. At Grand Portage, the huge canoes built for St. Lawrence and Great Lakes travel, packed with goods from Montreal, were exchanged for lighter, smaller canoes that men paddled up Canadian rivers into Ojibwe and Cree country. Located on the northwestern shore of Lake Superior in what is now northern Minnesota, Grand Portage became Waddens’ home.

Étienne Waddens became a hivernant or winterer, one of thousands of European men who spent winters with Native people in forts and Indian villages. And during the short days and long nights of winter, Europeans and Native people had sex, sometimes brief or violent, sometimes loving and sustained. Sex often evolved into settled relationships. European men expressed surprise at how quickly the “bewitchen vixens” became their “country” or “fort” wives. Large settlements of Cree and Assiniboine families gathered around Grand Portage every summer. Every fall they took traders like Étienne Waddens with them back to hunting camps. Étienne began a long and stable relationship with a Cree woman whose name we don’t know.

A “country wife” offered a trader like Étienne Waddens comfort and economic advantage. If Waddens wanted a band to hunt for him and trade at his post, he had to create a formal family relationship. Like many others in the fur trade, he remained married to his Montreal wife, but he also joined a Cree family. To do so he must have approached the Cree woman’s father and brothers in proper ways, bringing gifts and only then suggesting marriage. He had to meet Cree standards about how husbands should behave and how they should provide for their Cree families. If he failed to recognize his obligations to an entire band, he wouldn’t get many furs, and his new wife would leave him.

Often called mariage à la façon du pays, or the custom of the country, these unions mixed Indian, French, and British customs. Native people, fur trade companies, and the Canadian government recognized them as legitimate marriages. The Catholic Church also sanctioned such unions, insisting that priests marry people even long after such relationships began.

Though common, such unions involved risks, especially for women. Even European men whose families had lived in North America for generations lacked the survival skills that defined men in these indigenous societies. Their behavior was unpredictable. Some women were curious enough and attracted enough by the young Europeans to act on their own, but others felt pressure from their families or clans to do so. Either way, it took bravery to be guide and teacher, let alone lover or wife, to a stranger.

To ensure that such relationships served Cree or Algonquian needs, the women taught the hivernants how to speak their languages. They taught them how to hunt and trap animals, manage deep snow, and survive on the ice. Sex and relationships kept the hivernants in winter camps, but families made them loyal. With sex, whether within or without marriage, came children. The children of these unions helped secure a future for the tribe. A mixed-descent child would become a permanent link to the White trading world but also a member of an indigenous clan with resources and power.

For Native people, marriage demanded broad reciprocal arrangements that Waddens might not have understood. Husbands and wives provided for and cared about each other, but their marriage was one among many relationships that supported their lives. Marriages didn’t have to be lifelong, and people commonly had relationships that were same-sex or polygamous. Women knew that if they kicked out an abusive or lazy partner or if he left, their larger kin networks would support them and provide for their children. Extended families encouraged angry wives and husbands to forgive each other for various transgressions. If they couldn’t, unhappy people could try out other partners temporarily or separate permanently.

Étienne Waddens passed the test. His new wife, who spoke Cree, French, and other Indian languages, helped him to negotiate trade and daily life. As he learned Cree, he could convince his new relatives to hunt for him, expanding his business. His Cree family got better access to trade goods because of their relationship with Waddens, and they spread those goods throughout a network of villages. No marriage would be stable or fully recognized until the birth of a child. Marguerite Waddens, born in 1775, bound Étienne to his Cree family.

Marguerite was born at Grand Portage, where the Rainy River links the Canadian forests to the Great Lakes. This spot, on the booming western frontier of the fur trade, drew indigenous people and others from many regions. The Cree, watching the fierce competition between fur-trade companies, operated as crucial middlemen. Spreading south from Hudson’s Bay as the fur trade expanded throughout the 1700s, they allied with the Assiniboine, the Ojibwe, and the French. Many Crees became skilled with horses and moved to the Canadian plains to hunt bison. Other Crees, like Marguerite’s family, remained farther north and east, hunting large fur-bearing animals and small game in the Canadian forests. They made canoes, built fish weirs, and tapped maple trees. At the end of the eighteenth century, by connecting their lives to Native and European traders and goods, the Cree expanded in numbers and power. By the mid-1700s they controlled who hunted where, and their efforts meant higher payments for furs and lower prices for trade goods at Hudson’s Bay Company forts.

The business of fur was interrupted by waves of European war and North American imperial struggle but adapted. The Seven Years’ War, the longest and fiercest of the colonial wars fought between the French, the British, and dozens of Indian nations, overspread the region north, east, and west of the Ohio Valley. The region was claimed by New France but controlled by Shawnees, Wyandots, Delawares, Miamis, Illinois, Ojibwes, Sacs, and Foxes, who were drawn into the war on every side. When the war ended in 1763, after seasons of battle upset the fur trade along the St. Lawrence and at the Great Lakes, New France no longer existed in North America. Despite that formal change, thousands of French-speaking people, both Native and European, still lived and worked in the fur trade. The British were now in charge, but this had little impact on how the trade worked. Beginning in 1767, the British who took over from French governors in Canada “permitted” traders to winter in villages north of Lake Superior. That policy was simply catching up with how operations actually worked in a business that took European men ever farther into Indian Country.

Marguerite’s early life demonstrated how far the fur trade had spread over North America. As forts opened between York Factory on Hudson’s Bay and the Great Lakes, she and her parents left Grand Portage to winter in forts far to the northwest. First they stayed near Cree villages in the Saskatchewan Valley, and finally at the southern edge of the Athabasca country, nearly in the Arctic. At 58 degrees north, average daily temperatures in January were –6º Fahrenheit, and the sun peered anemically over the horizon only a few hours a day.

Marguerite learned how to smoke meat and fish, and how to make drinking water from snow over an ever-burning fire, facing her mother’s wrath if she didn’t tend that fire properly. She knew how to skin animals and preserve fur, essential to surviving Canadian winters. Like most traders’ children, she spoke Indian languages, French, and English. Also like most mixed-blood girls, she never learned to read or write, skills that would soon become necessary in a world of ledger books and letters.

Cree families with daughters like Marguerite had some advantages in the eighteenth-century fur trade because they had European men who were kin. Intermarriage could bridge chasms between clans, nations, and even fur companies. Like building bridges, however, mixing families also involved risk—bringing strangers and germs into Native communities.

Excerpted from Born of Lakes and Plains: Mixed-Descent Peoples and the Making of the American West. Copyright © 2022 by Anne F. Hyde. Used with permission of the publisher, W.W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.